Poor people are ugly

It was about halfway through Aussie horror The Babadook that I realised the stomach-churning anxiety I felt had less to do with the film’s monster than the social class of the protagonists: they were poor.

It was about halfway through Aussie horror The Babadook that I realised the stomach-churning anxiety I felt had less to do with the film’s monster than the social class of its protagonists: they were poor.

I don’t mean like you usually see it in movies, where poor people are the victims or perpetrators of violent crime or domestic abuse, or where they’re excluded by the camera’s fixed focus on the middle class and the suburban.

I don’t mean poor like on TV either, where the amoral antics of characters on shows like Outrageous Fortune and Shameless describe a cheerful underclass of roustabouts and ne’er-do-wells. Or worse, poor like in the endless iterations of TLC’s Extreme-whatever reality shows, where psychologically unwell people are reduced to caricatured depictions of the ‘hoarder’ or the ‘teen mom’ or whatever ‘honey boo boo’ is supposed to be (white trash for the sake of pointing and laughing?).

No, The Babadook hit because the single mum had to raise a troubled kid alone, while trying to hold down a shitty service industry job with inflexible hours and terrible pay and the claustrophobia of knowing you need someone to look after your boy when school’s done but you have to work to pay the bills, so who—? So instead of decided to cook meth (Breaking Bad) or rely on Grandma to go back to school (Boyhood) she just calls in sick, knowing she’ll get in trouble but putting her son before her boss. And when the shit starts hitting, as it tends to in horror, and she gets a bit soft around the edges, a little vague, and you suspect she’s about to make some terrible choices, as we’ve come to expect the poors must inevitably do when push comes, well — I’m not going to ruin the film if you haven’t seen it (it’s great), but it’s surprising.

When I realised what was bothering me about the film I tried to think of others with the same kick, but came up short.

Of course there are other movies about poor people. Will Smith captured the quiet desperation of a loving, penniless dad in The Pursuit of Happyness, and at home the unrelieved urban bleakness of Once Were Warriors compelled audiences sit up and shut up. Thing is though, the characters in these movies, though poor, are exceptional in a way that also makes them unrelatable. Smith – like Matt Damon’s character in Good Will Hunting – is a prodigy, able to solve a Rubik’s cube in thirty seconds. Temuera Morrison’s Jake the Muss is a broken thug, and though the film and its imperfect sequel do well to capture the generational nature of poverty, their characters don’t look, act or speak like most of the working poor who make up reality.

Imagine for a moment an idealised middle-class family: there will be mum and dad, a child or two, an animal, a small piece of grass out front or around back to play on, and perhaps, even today, a white picket fence. Now imagine an idealised poor family, an equivalent amalgamation of cultural tropes. Can you?

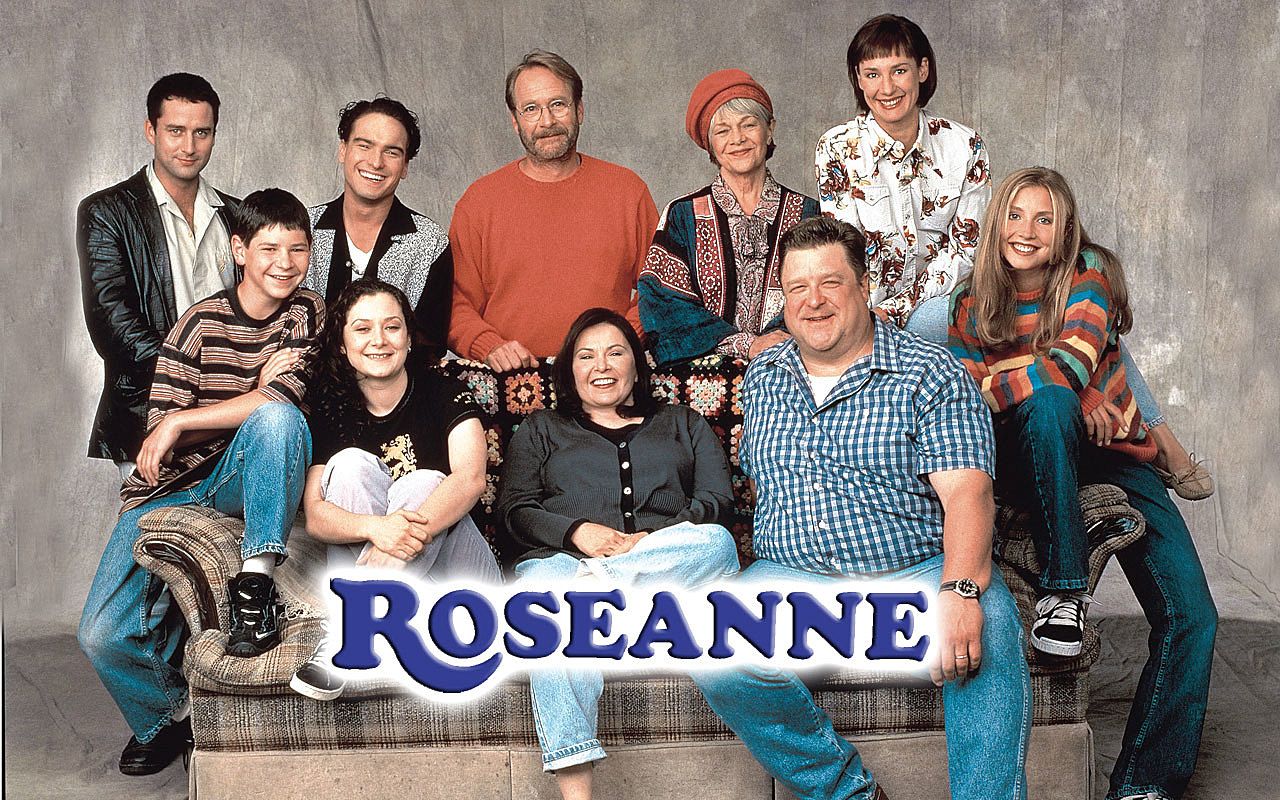

It wasn’t always quite like this. While now we watch comedies of ambiguously employed single 30-somethings like How I Met Your Mother or even Friends, there are calls to

repopulate the airwaves with shows like Cheers and Roseanne. Yes, they were comedies, but they were comedies that portrayed realistic lives of the working poor, and weren’t just created for our bemusement and mockery of “white trash” a lá Here Comes Honey Boo-Boo or Swamp People.

It’s half-tempting to ascribe this change to neoliberal reforms or late capitalism, but honestly, maybe it’s just a more sophisticated, sensitive entertainment industry. Poor people aren’t sexy. They’re not compelling, or broken, or brilliant. They’re the 47% and they don’t commit extravagant crimes or trouble the economy, so why should we watch them?

The obvious answer’s that while some entertainment's pure escapism, much of it aspires to artfully represent some aspect of the societies we live in. Films and TV are still where we see important representations of ourselves and each other, and we take our social cues in part from the reflected ‘normalcy’ we see on screen. If poor people are only ever violent criminals or passive victims or troubled addicts through the looking-glass, we might sloppily begin to believe reality conforms to that same standard. If they’re invisible, we might begin to think poverty is something that only exists in other countries while the news is on.

A less charitable reason we should watch poverty is that something about poorness lends itself quite readily to the horrific, and directors ought to exploit that. Perhaps it’s to do with the fact that honest representations of poorness feature people much like you and I, whereby it’s all too easy to place oneself in the shoes of someone who’s desperately struggling – the existential threat of barely treading water to keep the family afloat is at once an immediate and dull dread, like a half-forgotten memory of shame. It’s not the right kind of horror, though. Still, there’s something in the poor suburban spaces of films like Heavenly Creatures that offer themselves to horror particularly, and make me wonder why television producers and filmmakers don’t jump at the chance for a bit of affecting, effective social realism.

It could be we’ve become so blind to poorness as it actually exists that we’re incapable of representing its dull-eyed unremarkableness as anything but absurd, vacuous hyperbole.