Opening space: A review of ‘When Can I See You Again?’

Kari Schmidt reflects on the current exhibition at Fresh Gallery Ōtara curated by Molly Rangiwai-McHale and Luisa Tora, bringing together LGBTQI+ women of colour.

Kari Schmidt reflects on the current exhibition at Fresh Gallery Ōtara curated by Molly Rangiwai-McHale and Luisa Tora, bringing together LGBTQI+ women of colour.

When Can I See You Again?, at Fresh Gallery Ōtara, is an all-woman exhibition featuring queer, lesbian and bisexual artists of Māori, Pacific and Pākehā descent. As stated in the Facebook event page, this show is a “public invitation into a private, contemplative space” and in the view of co-curator Luisa Tora, acts as an alternative to a Pride week which is ‘largely white, glitzy and male-dominated’.

When Can I See You Again? is the classic question you ask a loved one in a text message, simple yet hopeful and a signal of a long-term relationship. Indicative of a certain levity in the artists’ approach to life and work, the exhibition uses this question to highlight the building of a community, “a community of resistance”, in the words of bell hooks.

Walking into the opening, this sense of community was palpable. It was a celebration. The works themselves are pared back with a line of framed, black and white photographs being the first thing to draw your eye. What About your Friends? (2017), a collaboration by artists and co-curators Molly Rangiwai-McHale and Luisa Tora, is made up of 18 photographs of the pairs’ friends and family. The photographs are accompanied by a zine which asks simple questions such as: “Where do you live?”, “What would you save in a fire?” and “What is your perfect day?”, all met by a variety of answers.

This work was influenced by bell hooks’ essay ‘In Our Glory’, where the author examines the role of photography in the lives of Black people alongside the advancement of Black civil rights in the United States. hooks discusses the struggle of Black people to create: “… a counterhegemonic world of images that would stand as visual resistance, challenging racist images.”[1] Representation and image making are thus identified as crucial aspects of the struggle for equality in America. As hooks states: “The history of black liberation movements in the United States could be characterized as a struggle over images as much as it has also been a struggle for rights, for equal access.”[2]

Placing these women of colour on a gallery wall is a powerful gesture, an assertion of community and a claim to space.

New Zealand’s struggle with racism is arguably not as visible as that of the United States. However, due to our colonial legacy, New Zealand does have similar social issues in light of poverty, disproportionate incarceration rates and health issues faced by Māori and Pacific people. Image making too, is part of this dynamic, with Māori and Pacific people commonly depicted within negative stereotypes associated with either poverty or violence. Placing these women of colour on a gallery wall is a powerful gesture, an assertion of community and a claim to space. The diverse women photographed are a testament to the multiple experiences of queer, lesbian and bisexual Māori and Pacific women and the fact that there is no one narrative.

Ideas of representation continue in Kerrie Van Heerden’s Untitled 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2017), where the artist re-appropriates comic book images of women sourced from books found at an op shop. She then re-presents them on white card. Typically, women in comic books such as these are secondary characters, often objectified and over-shadowed by their male counterparts. Yet, by removing these images from their original source material, the artist enables these powerful women to stand on their own, highlighting their strength and autonomy. By depicting these images in isolation, the artist re-writes the narrative the characters belong to, including an image of two women in an ostensibly romantic moment, locating them within her own reality.

The words ‘so gay’, used in the pejorative throughout Berry’s upbringing, are reclaimed in being association with the safe space and community of the LGBTQI+ club scene.

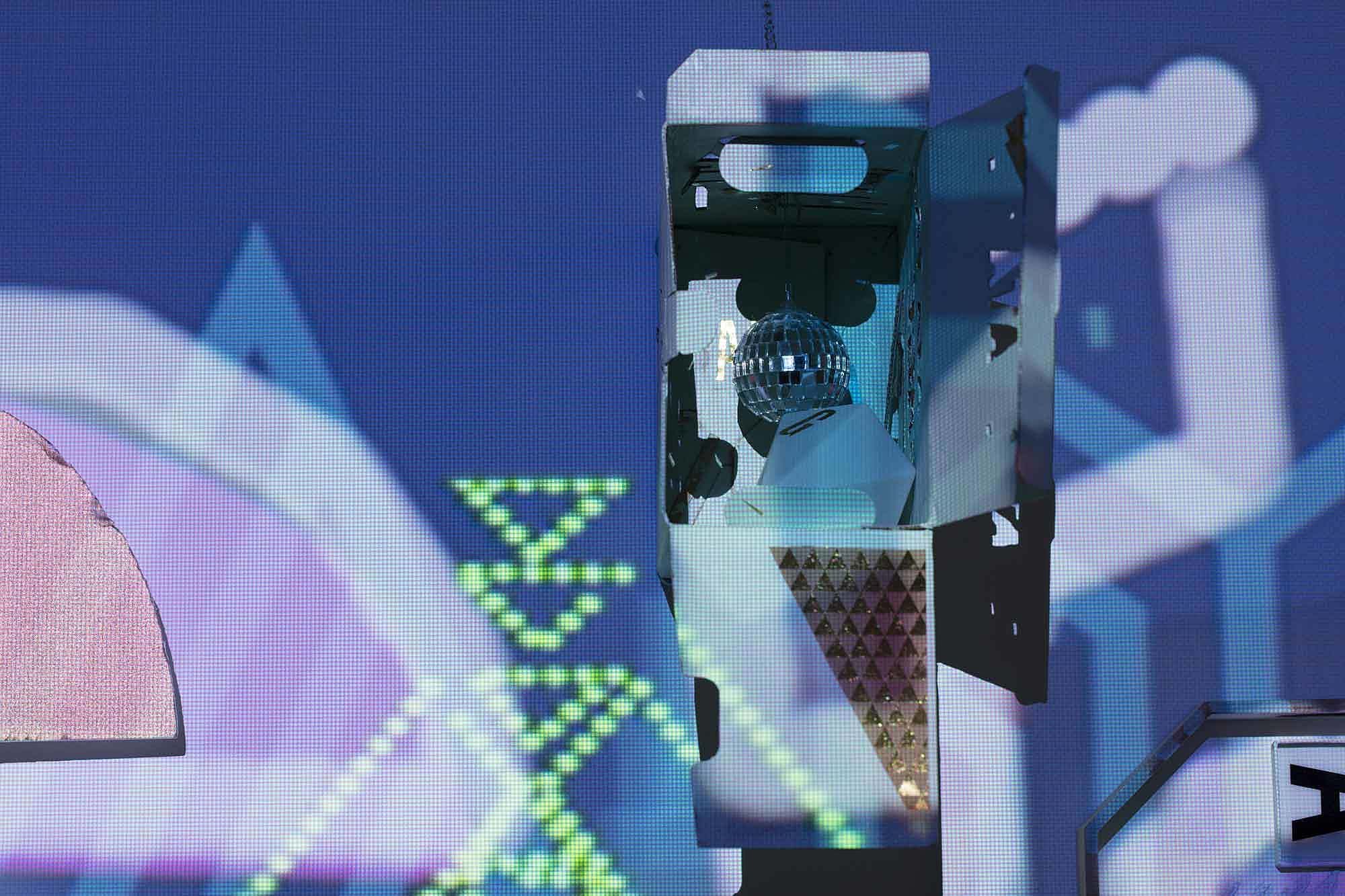

Jamie Berry’s mixed-media video, ATA bay (2017), features a soundscape, which is produced with data from the artist’s own DNA. The playful and upbeat dance music is coupled with colourful abstract visuals, reminiscent of the 80s aesthetic of Berry’s childhood. These visuals are projected onto a number of postboxes-cum-bird houses and intersected with images of New Zealand land and cityscapes. For the artist living between Wellington and Gisborne this is a work about home. The words ata (meaning ‘whatever’) and bay (referencing the colloquial term ‘bae’) reference the artist’s birthplace of Ata Bay and appear throughout the work. The words ‘so gay’, used in the pejorative throughout Berry’s upbringing, are reclaimed in being association with the safe space and community of the LGBTQI+ club scene. ATA bay also features birds, which represent members of Berry’s community, some of who have passed away. They stand as guardians. The owl in the middle of the work, and tattooed on the artist’s own body, is one example, and represents Berry’s friend who died of breast cancer at the age of 33.

The theme of a community as a form of guardianship was further represented in Sangeeta Singh’s painting, You’ll find me in shallow waters/Dive deep (2017). The painting depicts a flowing river, alongside a serpent figure, leading into a dreamscape where one can see figures, intended to represent the artist’s community standing as guardians or sentinels. The imagery of the body of water and the serpent both draw on Singh’s Indo-Fijian heritage referencing various ancestral journeys. The serpent Kaliya is from an origin story that tells of how the Indo-Fijian people were sent to Fiji by Krishna. The water reminds us of the artist’s ancestors’ journey across oceans to Fiji to perform indentured labour.

Ana Te Whaiti similarly speaks to her ancestry in dedicating her work Rere (2017) to the memory of her grandmother. Three plastic garments (two jackets titled X / O and Rays of Sunshine / Waves of EMOcean and a wrap skirt titled What are the Odds?) are hung in the gallery space. Within each garment are various patterned textiles. The same pattern is coloured differently, producing three different iterations. With different fabrics on both the inside and outside of the garments, Te Whaiti suggests a disjunction between how we experience ourselves subjectively and how others interpret the performances that our personalities consist of.

In Tasi Sua’s sculptures No Flys on Me (2017), plastic sheeting similar to a butcher’s curtain is hung up in three separate box shapes. We see a different image cut into each sheet of plastic; the symbol that represents women on female toilets; a person peeking from behind the curtain and; a puletasi (a traditional Samoan female dress). These three sculptures embody the personal trauma of the artist’s gendered experiences such as being questioned when walking into a women’s toilet; having to wear a traditionally female dress and her tentative attempts to peek out from behind the fear this has generated, to participate and to be seen.

Safe spaces such as this enable these artists to reveal deeply personal narratives unique to their identities as LGBTQI+ women of colour.

In discussing their works with me, the artists and curators gave me a privileged insight into their world, otherwise unobtainable with the lack of any exhibition text. With such important subject matter, a well-crafted text would serve an outside audience well. That aside, this exhibition is a refreshing break from the existing central city Pride narratives. And there is no doubt that When Can I See You Again? gives these artists turangawaewae, a place to stand within their communities. This is enabled by Fresh Gallery Ōtara, a safe space which is located in South Auckland where these artists can have a public voice. Safe spaces such as this enable these artists to reveal deeply personal narratives unique to their identities as LGBTQI+ women of colour.

In When Can I See You Again? we are privileged to bear witness to these artists’ private spaces, which are characterised by tribulations, yes, but also love and a resolute pride.

[1] Hooks, bell. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press. 54-64) at 57.

[2] Ibid.

When Can I See You Again?

Fresh Gallery Ōtara

17 February – 25 March, 2017

Images by Sam Hartnett, courtesy of the artists and Fresh Gallery Ōtara.