This Broken Ladder: Why Women Still Can’t Make It In The Legal Profession

Admissions of female lawyers have outnumbered males for the past two decades, yet men still outnumber women at the top levels of the profession. Why? Di White looks at what's going on.

When I was 17, I decided I was going to be a lawyer. I had my reasons: some good (wanting to help people), some misguided (actually being able to help people), and some cringe-worthy (Erin Brockovich) (who am I kidding, Legally Blonde). Something that never factored into my decision-making process was my gender. I had grown up as part of a generation of girls told they could do anything. The law was yet another profession that, while once the sole domain of men in terms of both its creation and application, was now welcoming women with its arms wide open. As the Spice Girls so aptly put it in one of their lesser-known hits, Ain’t No Stopping Us Now, “There've been so many things that have held us down/But now it looks like things are finally comin' around.” If I wanted to be a lawyer, the fact I was a woman was not “stopping me now”.

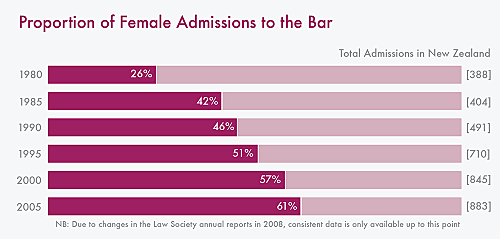

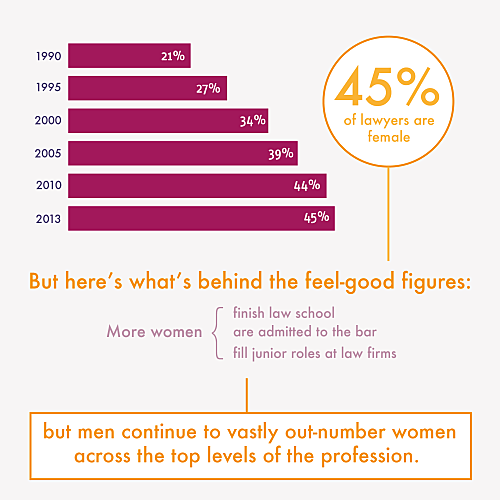

A cursory glance at the numbers and it would seem the Spice Girls, in all of their wisdom, were right. The barriers to women entering the legal profession have never been lower. In just over 20 years, the proportion of women in the legal profession has risen from 21% in 1990 to 45% in 2013. The majority of new entrants are female, meaning more women are graduating from law school and more women are getting admitted to the bar than our male counterparts. In terms of entry into the profession, the law appears to be nearing a perfect ten in terms of gender equity.

Digging a little deeper, or a little higher in the profession’s hierarchy, the shine begins to fade. Almost half of all female lawyers are in their first ten years of practice compared to only just over a quarter of all male lawyers. Looking at the higher end of the experience scale, 50% of male lawyers have more than 20 years’ experience, compared with only 20% of female lawyers. Like any profession, experience often translates into career progression. With figures like these, it’s no surprise that only 28% of judges and 14% of Queen’s Counsel respectively are female.

At law school, I remember looking around lecture theatres predominately made up of females – intelligent, articulate, smart thinkers and speakers – and mulling over this disconnect. The most obvious explanation is that those intelligent, articulate, smart female legal minds were fewer and further between 25 years ago when today’s judges and partners were progressing through law school. There is a grain of truth in this, but it’s just that – a grain. The reality is that the number of women graduating from law school has been at least on par with men for long enough to suggest other factors are at play. While females may have not been in the majority at law school 25 years ago as they are today, they were certainly not in the minority that female partners, Queen’s Counsel and judges are now.

Simply put, here’s what lies behind the feel-good figures: while more women finish law school, are admitted to the bar and fill junior roles at law firms, men continue to vastly out-number women across the top levels of the profession. If you’re a young woman who has just started out in your first job after law school, there is a good chance you’re surrounded by a large number of women at your level – but that you predominantly answer to men. And if you’re a woman who’s ascended to the top levels of the profession, you’re likely to be one of a select few.

Eight years on, I often find myself questioning my decision. Why do the top levels of the legal profession – a profession ultimately concerned with justice and fairness – still look and feel like the quintessential boys’ club? What does the future look like for a young female lawyer in 2013?

Perhaps the most oft-cited reason for the dearth of women in the higher ranks of law firms is a lack of flexibility in working hours. Firm life in its current form is inherently, and fundamentally, hostile to family life. And in a society where women are still expected to be the primary caregiver, hostility to family life becomes a proxy for hostility to women.

After graduating, Ella (whose name has been changed) spent two years working in a major commercial law firm, primarily in bankruptcy and insolvency – two of the most male-dominated areas of commercial law practice. Like me, Ella never applied for any internships or graduate positions, and was genuinely surprised to end up at a commercial law firm. “I got a job at a big firm just after I graduated as a kind of a happy accident,” she said. “I really enjoyed it for the first year or so, but I became quite disillusioned with the work, the environment and the people. I realised what got me out of bed in the morning wasn’t what made big firms tick.”

It’s fair to say that what makes “big firms tick” is pure and simple: money. Lawyers bill their clients – often at nothing less than exorbitant rates – to make money for their direct supervisors, the firm’s partners. And beyond the tick of the billing clock, as it rakes in hundreds of thousands of dollars, the work is also about money: making money, protecting money or avoiding liability for a corporate client. No matter what way you look at it, your existence in a big firm is by in large both driven by and derived from the dollar. It was an increasing discomfort about this existence that led Ella to, what she coins, “get out”.

Ella recently made the shift to the public sector and now works as an in-house lawyer for a government body. She’s no exception: the public sector has become something of a haven for women working in the law. When I asked Ella about the difference between her former role at a private firm and her new position in terms of culture, she didn’t hesitate for a second: “Almost the entire staff at my new office are women. That means there is a lot more support for people with families.” Her sentiment is reflected in the stats: in-house practice, be it working for the public sector or other companies, is the only area of practice women out-number their male counterparts, with 57% of all in-house lawyers being women.

Many law firms will argue that flexible working arrangements are available; that there is a willingness to accommodate women who want to raise families. “The big firms – especially these days – talk a lot about making work easy for women at senior levels in terms of maternity leave, flexible working hours, and part-time work,” Ella observed, “and my impression of that and how it works in practice is that it is all bullshit.”

In reality, flexible and part-time work almost inevitably takes the form of full-time work – minus the full pay cheque and appropriate recognition. Women working in major firms three days a week work, physically, three days a week in the office, but they’re also working weekends and remotely from home simply to keep up with what is essentially a full workload. If these women don’t keep up, they don’t get the work; and if they don’t get the work – if they are relegated to work beneath their expertise and they miss out on the big clients – their careers begin to stagnate. Regardless, when the firm looks at whom to progress up the hierarchy, it’s very rarely the “part-time” mother.

Ella claims that in major commercial legal practice she has never seen a part-time working arrangement actually work. She puts this down to a lack of willingness on the part of the firm to change their practice at a more structural level. Her experience was that women who worked three days a week were simply said to be “not in the office on Thursday and Fridays”, rather than the firm putting in place a system that would allow the women to only work the three days for which they were paid, and would still enable them to work on important files with major clients:

“The way law firms, at least big law firms, work hasn’t really changed for… ever. It’s client guided. Your client needs you to be available all of the time, so that’s the business model. Firms don’t work the flexibility in for their staff. I think the problem is that firms haven’t thought outside the traditional ’one person as a main contact for a big client’ model, and I don’t think they’ve thought about how to make it work for part-time people to be part of those big corporate contact teams.”

Essentially, women working part-time are treated as if they are one-off unique arrangements. In fact, if systems like Ella suggests were implemented, and there was a shift in the dominant model of client interaction and service provision, perhaps part-time arrangements become more commonplace and, importantly, actually work: women could engage with major clients alongside a team of other lawyers in a way that meant part-time work was just that: part-time.

When comparing the work environment of private firms and public sector in-house practice it’s glaringly obvious why we see why so many women make this shift – and why there’s a lack of women at the top of the legal profession. Within a short time of starting her new role, Ella noticed a marked difference in the way parenthood operates in a public sector role. Children are often in the office, part-time working arrangements are commonplace, and women are progressed into high-level roles. The essential difference is that structures are put in place to ensure part-time work arrangements work for all parties – the lawyers, the organisation and the client – rather than the more ad-hoc approach in firms.*

Geof Shirtcliffe, a partner at one of New Zealand’s leading commercial law firms, Chapman Tripp, is more optimistic about both firms’ willingness to accommodate working parents and shifts in attitude within the profession. Geof, an expert in corporate and securities law, has been a commercial lawyer long enough to know the situation for working parents was once far worse. He recalls a conversation 20 years ago with a number of colleagues who argued it simply was not possible to be an active parent and a partner. Rolling forward 20 years, a number of his fellow partners have some parental responsibility, himself included. Since becoming a parent, he has noticed what he deems a shift in business culture more generally. If he wants to go to a Hi-5 concert or a school event during work hours, he can – and does: “What has struck me is I have never, ever had an occasion where my colleagues or my clients or anyone else I am dealing with has given any indication that they think that’s an inappropriate thing to do,” he says. “I really think the business world has its head much better around the fact people have important parts of their lives to which they need to attend.”

The advent of smartphones now means the office is only ever a slide of the lock screen away,and the notion of “open business and close business” is a quickly fading memory.Geof argues that this allows for greater flexibility in terms of when the work gets done: he can be off for the afternoon watching his child play sport, and in bed at 11pm firing off emails to a client ahead of the next morning’s meeting.This degree of flexibility, he believes, works in favour of women, in particular, given the fact women are still primarily the primary caregiver.

Geof is adamant, though, that flexible working arrangements will only work if there is flexibility on both sides. He’s realistic about the fact commercial firms are delivering a niche, high-end service. Clients pay large sums of money not only for high-quality work, but also for timely and responsive service – a type of service not naturally compatible with flexible work arrangements. He recounts hearing a female senior partner at a major US law firm talk on flexible work practice:

"One of things she made very clear is that flexible work arrangements are not just a question of the law firm saying ‘OK, you can work three days a week’. It’s actually a two-way street. She said, ‘Look, we have associates who are mothers and want to work three days a week, and that’s fine. But god help them if they have their Blackberry off. If they’re sitting in the playground supervising their kids on the swings, that’s great but if one of their key clients needs to get hold of them, they better be monitoring their Blackberry."

Geof’s comments reflect the very issue Ella witnessed in her firm. In major firms, the work arrangement may be flexible, but the work itself is not. Flexible hours only go so far to address the problem. Flexibility in terms of when and where work can be done is helpful when you need to factor in the one-off school function or sick nanny. However, a 24/7 Blackberry kind of policy ignores the reality of parenting – a full-time job with demanding clients of its own. It’s not a supervisory role that can always be simultaneously juggled with other tasks. Can you really “monitor” your Blackberry if your full attention is devoted to a toddler fresh on their feet and eager to explore? Should a part-time parent be expected to simply “supervise” rather than “parent” on a trip to the park? It’s fair to expect a degree of flexibility when exceptional circumstances present, but premising a flexible part-time work arrangement on the fact the parent will be constantly monitoring their Blackberry (and therefore, constantly “in” the office at least in terms of headspace) seems destined for failure.*

As a woman in the legal profession, you cannot help but feel a niggling sense of not quite belonging. Sometimes, in fact, you plainly don’t belong. Last year, the Hawkes Bay branch of the Law Society held its annual Christmas Party at the Hawke's Bay Club, what is essentially a men’s only club. While the club claims women can be put forward for membership, to date not one woman has been inducted to the club. There was no question as to whether women would be able to attend the Christmas function (they were) but, in a profession plagued by gender issues, it’s presents as bizarre choice of venue. The club itself sends the very same message that the profession has been sending for decades: women who join are the exceptions to what is otherwise a man’s profession.

Another example is in client entertainment, a major part of vying for new clients or maintaining old, lucrative clients in corporate law practice. Invariably, client entertainment functions involve three core things: 1) alcohol; 2) sport (90% of the time rugby, cricket if rugby is unavailable); and 3) more alcohol. It is not that women are not capable of enjoying those three things. But it’s hard to argue that a corporate box with Steinlager Pure on tap is a female-friendly environment. It’s hardly a family-friendly environment. It’s definitely not a pregnant-woman-friendly environment. A friend working at a commercial firm describes to me the client fishing trip her firm put on. Fishing. “God, I hate fishing”, I remark. And I do. I cannot think of anything less related to my profession than throwing dead fish into the water so I can kill more fish. And yet, in what at times feels like a profession trapped in the dark ages, client bonding remains about a bunch of men going away to hunt animals.

It’s hard to reconcile client fishing trips and men’s only clubs with law firms’ purported efforts to be more female-friendly. It’s the insidious nature of this kind of disadvantage that makes it so hard to change. Of course women are free (well, usually) – and indeed, encouraged – to attend these and similar events. However, it’s that flawed notion of choice: in reality, these are not environments that will appeal to most women and they are almost certainly not environments that are conducive to progressing women. Promotions not only come off the back of success in important cases and happy clients: they come too from late night bonding sessions over a few too many whiskeys. It’s no secret – across any profession – that relationships are essential to career progression. Where that becomes problematic and indeed disadvantageous is where those relationships are carved out, nurtured and solidified in environments where women are – albeit not on the surface, but very much in practice – excluded.

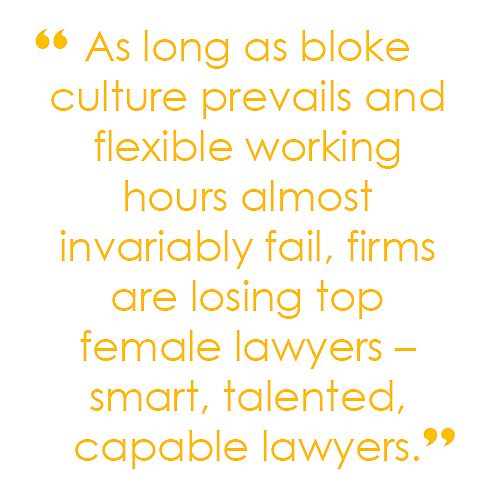

Would I go on a firm fishing trip if that was part of my job? Maybe. Would I find myself in a job where a fishing trip was part of my job? Unlikely. People like Ella and I will invariably not end up at major corporate law firms. It’s this point law firms seem to be missing: not only women serve to benefit from a change in firm culture. As long as bloke culture prevails and flexible working hours almost invariably fail, firms are losing top female lawyers – smart, talented, capable lawyers. If making a firm more female-friendly is as simple as swapping fishing for a less gendered form of client entertainment, and telling a client they have not one but two lead contacts, one of whom works part-time, and this means keeping some of the firm’s best lawyers, surely that’s a change worth making.

Geof assures me firms are well aware of what they stand to gain from addressing these issues. “We don’t do things just because we’re nice people: I think there’s widespread, 100% consensus in the partnership that it is the right thing to do, but there’s a business imperative in all of this.” He argues that it’s not just about the fact firms are losing top female lawyers: “There’s a longer term business imperative in that if we get all of these bright women through and none them come through to partnership – or at least very few of them do – and let’s not throw away talent. But there’s also a more immediate one, which is that more and more of our clients are women.” Geof recounts a partners’ meeting about ten years ago at which the then CEO of Westpac, Ann Sherry, spoke about the changing face of the corporate world. “She said, ‘you guys need to be aware that there are increasing numbers of women and women will look around and say why do I want to give my work to a bunch of blokes’. And I remember thinking ‘shit, that might be right’.”*

While reluctant to indulge the “we have a female Chief Justice so everything is OK now” mentality, and generally at pains to avoid the inevitable complacency that goes hand-in-hand with the “but we’re trying”, I’m hopeful the situation is improving – in firms, corporate culture and indeed wider society.

Despite the striking gender disparity that still exists at the top levels of law, there does seems to be some genuineness in firms’ attempts to effect change, albeit small and not necessarily structural. Rae Julian is National President of the New Zealand branch of UN Women, one of the many limbs of the UN and one that is concerned with women’s empowerment. She jokingly self-describes as “one of those beady-eyed women back in the 70s”, and her career spanning over 40 years includes time as a teacher; head of a Parliamentary research unit; a Commissioner with the Human Rights Commission; time serving on UN Missions abroad; and prior to her current position, Executive Director of the New Zealand Council for International Development. She is currently spearheading a project aimed at addressing gender issues in law firms. The project aims to get a commitment from law firms to the UN’s Women Empowerment Principles, a set of principles designed for businesses which seek to empower women in the workplace, marketplace and community. In working alongside the Human Rights Commission, Equal Opportunities Office, and business groups such as the Chamber of Commerce, the project aims to get law firms to commit to implementing the principles and encouraging firms to promote more women.

Though the project aims to generate a general commitment to the Principles, it also seeks to establish firm-specific goals. Firms are asked to fill out a questionnaire focussing on why they signed up to the project, and from that tailored goals can be created. While each firm will be different, the lack of women in senior positions is likely to be a common thread.

Roundtables about the issues facing women in the legal profession are one way UN Women has been engaging with firms. Rae describes going to one such event and talking to a large group of women lawyers from one particular firm. It soon emerged that not one partner, and only one associate, from the firm was a woman. Rae is hopeful that firms like this will benefit from a commitment to the Principles. She was optimistic that, in this instance, the attendance of such a large number of women from the firm signalled a desired for change. “They agreed that they should tackle it as a group rather than saying individually ‘why not me’”, she recalls. “They thought it was the wider principle they should be tackling.”

Progress like this also leaves me feeling, somewhat tentatively, hopeful about a shift in firm culture. It is frustrating to hear women claim gender equity is not an issue in law: that we’ve reached a nirvana of equality so put out the flames of your burning bra. But more frustrating, and perhaps frightening, is when women seek – albeit often unconsciously – to benefit from this myth. In this environment, when a women comes out loudly and proudly saying she doesn’t need a leg-up, that she got to where she is regardless of her gender, she not only kicks the ladder out from beneath her but effectively bends down, picks it up and climbs a bit further. If women from within firms seek change irrespective of whether it’s in their immediate best interests, that in itself is progress.

Even more heartening is to hear men in firms recognise that gender inequity remains a major issue for the legal profession. I remark to Geof how refreshing it is to talk to a male partner who seems to have a genuine commitment to addressing these issues, given that many within the legal fraternity argue until they’re damn near baby-boy blue in the face that women and men have equal opportunities in the legal profession. “That’s just silly”, he says, “Without getting into a whole Larry Summers debate about whether there are fundamental differences between men and women, you just have to look around: it’s just much more likely that women are going to take on significant parental roles. It’s not ineluctable, whereas a generation or so ago it absolutely would’ve been, but it’s still on average much more likely.”

Like Rae, Geof is optimistic about the fact the profession is changing: “I think, like all change, it doesn’t happen quickly enough for a lot of people. And I think it’s easy for me, as a white, middle-age, middle-class male to take a relaxed and benign view on the speed of change. But nonetheless I do think that things are changing.” While by his own admission the number of female partners at his firm remains “not nearly enough”, the firm has undertaken a number of measures to address this. The firm’s “inclusive leadership programme”, initiated with the assistance of Deloittes Australia, has sought to understand and address some the underlying cultural factors underpinning the obstacles to female progression. It’s the deeper and more nuanced approach to the issue that Geof believes makes the program different. “They’ve got us focussing on is things like homophily, in-groups and out-groups, and the sort of cultural factors which can mean that with the best will in the world you can think you’re a meritocracy but you’re not actually a meritocracy.”

The “lawyer” in me can’t help but feel cynical that Geof remains the exception and not the rule in terms of attitudes towards change in the profession. In order to find any solution, it must first be accepted there is a problem. I am far from convinced the legal profession has even reached this stage. The number of female law graduates is used time and time again as a tired example of the fact the profession has now reached some kind of gender nirvana. It’s not uncommon to be told – by both female and male lawyers – the lack of women in partnership or judicial positions is because of “choice”. I have no doubt that if Geof represented the mainstream opinion on issues of disadvantage and discrimination within the profession, we’d be a lot closer to that nirvana. But he doesn’t, and plainly we’re not.*

It’s not just the rigidity of the profession or the inability to provide workable solutions for part-time parents that has led to the disparity between women and men at the top levels of the profession. Indeed, this is not the only issue facing women working in the law. There’s no doubt that while some of the issues facing women in law are structural and institutional, some are simply the same tired, overt sexism women have been facing in the workplace since women have been in the workplace. A recent event hosted by the Auckland branch of the New Zealand Law Society (see page 26) provided female lawyers with tips as to how to best apply make-up on the go, and how to “whip a tired hairdo into a chic French knot with glamorous results”. While the programmes aimed at progressing females in the legal profession are usually well-intentioned, and some do provide useful mentoring and role-modelling for young women entering the profession, events like these reinforce the idea that women lawyers are nothing more than pretend lawyers playing dress-ups while the real blokes get down to the serious business.

Despite undeniable progress, women who enter the legal profession still enter a man’s world. If we want to succeed in this world, we do so largely on male terms – whether it be in the way firms function in terms of work ethic and rigid working arrangements, or the way firms engage with clients. Law, no matter how loudly and vehemently people will protest, still largely operates on a base assumption that the people writing, applying and indeed using it – especially in a commercial sense – are men. Progress is being made, but at times it feels superficial: the same structures that have long discriminated against women essentially remain in place, and the changes appear to be tweaks rather than the necessary systemic change if we are see a real shift in legal culture. A legal profession that not only enables female participation and progression, but actively facilitates it, will benefit not only female lawyers but firms and clients too. It’s a win-win game, if only today’s major players would see it that way too.