Why Can't We All Just Get Along? The Curatorial Edition

Indigenous curators Nigel Borell, Ioana Gordon-Smith and Ema Tavola tell Visual Arts Co-Editor Lana Lopesi what gives them hope and what frustrates them within New Zealand curatorial practice.

In a world full of unexpected, unknown and unconscious bias – our own and other people’s – sometimes it feels easiest to stand in our own monocultural or monogender corners, feeling lonely, looking at our toes, too shy and scared to talk to or about each other. But. Ew. How do we have fun together without inadvertently fucking each other off? In this 4-part series looking at visual arts, literature, theatre and public commentary, we ask some experts for their ideas about how we can all get along.

Edition 1: indigenous curators Nigel Borell (Pirirākau, Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Te Whakatōhea; Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki), Ioana Gordon-Smith (Samoa; Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery) and Ema Tavola (Fiji; independent) tell Visual Arts Co-Editor Lana Lopesi what gives them hope and what frustrates them within New Zealand curatorial practice.

Before this discussion took place, the name of the whole series was going to include a riff on “intersectionality”. Nigel, Ioana and Ema’s thoughtful challenge to that word instigated a change in our thinking, back toward words such as ‘sovereignty’ which have not lost their potent meanings.

The discussion took place in the boardroom of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki; thanks to Nigel who checked it was free after the first venue, the Gallery’s café, turned out to be too noisy for the recording.

This conversation started with two hype words, ‘intersectionality’ and ‘ally-ship’. Intersectionality really is about relationships, understanding that all oppression is connected yes, but is not the same. Ally-ship is the enacting of intersectional thinking, it is understanding various positions of privilege and using them to support someone else.

For example, ally-ship is the white protestor using their body as a shield for the black protestor from police violence because the white protestor understands that because they are white they are less likely to become victim to police brutality.

The editors at Pantograph had discussions about who we wanted to be a part of these conversations. We considered asking gallery directors (who are mostly Pākehā), those who hold the power in our institutions, for their thoughts about intersectionality and ally-ship. But that would shift the voice in a conversation which is about ‘otherness’ into the hands of those who have an opt-out, those who never actually have to consider these ideas in their everyday lives. For today, those whom I am asking to lead the conversation, and whom I am asking to set the terms of how to be a curatorial ally to indigenous people, is indigenous people.

I have real problem with those terms because they’re not ones that I subscribe to or find articulate the hot issue for me as a Māori person.

Lana Lopesi: To get us started I want to throw this proposition to you all: how do we ensure our colleagues/directors/curators/institutions think intersectionally – or understand intersectionality – to enact ally-ship?

Nigel Borell: I have real problem with those terms because they’re not ones that I subscribe to or find articulate the hot issue for me as a Māori person, or for Māori people that I am trying to represent. For me, they represent the dominant culture and exist as a way for others to try to understand me and, to a large extent, that’s a white conversation. I do question whether these are just neoliberal conversations.

Ema Tavola: I think Nigel has hit the nail on the head. The first time I heard the term ‘intersectionality’ was from a Pākehā woman who was speaking about it in such an empowered way, but it had nothing to do with me. I’ve always felt it was a word that didn’t belong to me and that I am not part of, the power of the term does not sit with the oppressed. Being at the intersection is about understanding a relationship, and from an indigenous perspective we don’t just know about the other party, it’s about a face-to-face relationship, engaging with custom and having meaningful exchange.

Intersectionality at its worst is a way of policing and rule making for white people.

Ioana Gordon-Smith: It’s funny, I actually came into this conversation expecting everyone to be a big fan of intersectionality when I had so many queries about it. Intersectionality at its worst is a way of policing and rule making for white people. It’s a way flattening out the greys and telling people ‘yes you can do this’ and ‘no you can’t do that’ and I am not interested in telling dominant culture what they can and can’t do. More fundamental for me is making sure indigenous people have a presence in the gallery. So us talking about intersectionality and the cross-section of various oppressions felt in the world – it seems like such a negative way of looking at the world. What I want to do is empower people and audiences.

In terms of ally-ship I have two thoughts. First, curating is inherintly ally-ship, being an ally to the artist and the audience.

NB: I agree but I would never term that ‘ally-ship’. I would just say that’s being a good host or showing manaakitanga and whakawhanaungatanga [the process of establishing relationships]. I think that way of working is inherently indigenous. But I could see very much how someone outside of that [indigenous framework] would call that ‘ally-ship’.

IGS: True. My other thought is that ally-ship is also self-congratulatory, as it acknowledges your role within the space rather than just handing the space over. Maybe you [the Pākehā or tauiwi curator] should just vacate.

NB: Those other points you talk about, Ioana, describe this term white fragility, which is to do with how they [white people] respond to injustice and wanting to do well and wanting to understand their own uncomfortable nature with certain issues.

I bring that up because it’s important to question these terms and ask do they have relevance to us – ally-ship: for whom? By whom? – and if they need to be reconfigured to keep us at the centre. We need to be at the centre of our own conversations, we have been at the margins long enough. Let’s reposition the conversation.

Ally is a war term; we are not at war.

ET: It does feel like steering the waka in a different direction to talk about intersectionality when we have all been a part of a cultural revolution, and we all benefit from the last 30 or 40 years of decolonisation. Intersectionality is not the thing propelling us forward. The most powerful ally-ship example sits within dominant culture, it’s when someone who has taken the time to open their own minds about inequality and oppression talks to their own people. An example of that is when large arts organisations in Auckland discuss how to broach diversity as something that has whole organisation benefits, not simply for the benefit of diverse audiences. Those conversations in a Pākehā environment are the most beneficial for us [as indigenous people]. We don’t have enough numbers at the table, enough power or enough advocates to make large-scale structural change in the arts and cultural sector. I actually prefer the word advocacy to ally-ship. Ally is a war term; we are not at war.

IGS: I want to pick up on what Nigel said about intersectionality being a neoliberal thing. In a way, it silos all of our different forms of oppression while evenly making everyone the recepient of oppression rather than agents or beneficiaries or perpetuators of certain types of oppressions. It puts everyone in their own little cubby.

LL: So I think we’ve established that intersectionality and ally-ship are not the terms for us, they remove a sense of social responsibilty and make people feel as though they are doing more than they actually are in [curatorial] practice, and that we need a Moananui framework for this conversation.

To bring the conversation back to practice I want to ask you all, what conditions are needed for Pākehā and/or tauiwi curators to work with indigenous artists and artists of colour for it to be a mutually beneficial relationship?

The dominant culture has ‘all the cards’ and it’s a vulnerable position to hand over half of them.

NB: It comes to the basis of power. Who holds the power in those conversations is inherently important for Pākehā or tauiwi curators to understand because often when you are the dominant culture or voice you are in a position of power and you don’t even realise it because it’s the norm. The dominant culture really needs to think about how power structure informs those conversations. I would think that in a practical sense that would mean saying to an artist: “you know what, I am going to work with you to create this exhibition and I’m not going to make any assumptions about how we go about that but instead trust that your knowledge and voice will inform how it moves forward.”

I know a lot of institutions say that they share the power in this way, but I don’t think they really do, and definitely not in the ways that they think they are.

IGS: To pick up on that, I do think that there is only a certain level of power that institutions are willing to abdicate. What I mean is that there is a level of leniency that is allowed and that gesture is being seen as the all. Institutions need to bear in mind that while they have given over some power, they haven’t given over all of it.

NB: The dominant culture has ‘all the cards’ and it’s a vulnerable position to hand over half of them. It’s a challenge to the institution isn’t it, to give over half of the cards and say “let’s do this together”. I mean you have lots of experience in this area… [gestures toward Ema]

Currently Pacific artists are the ones who are brought in to change the audience and bear the burden; told to “bring your people”. That’s just tokenistic and offensive.

ET: [gestures to a poster on the wall advertising Home AKL, which Ema was Associate Curator for. Everyone laughs.] The thing that comes to my mind is the practice of cultural safety in the health sector. That practice started with Māori nurses and, in part, relates to the idea that anyone dealing with Māori in the sector in any way must, must, must understand the 200 years of history that has gotten them to this point; must understand that the inequities and inequalities that currently exist for indigenous people and others in this country are the product of 200 years of colonisation or contact. So, cultural safety is the practice of understanding all the things which have affected the position of where Māori are today. And that concept of needing to have a historical understanding of oppression is something that we don’t see in the cultural sector and something that we would benefit from hugely. Programmers and curators in mainstream institutions need to understand the social and political history of different groups of society and their intersections over time, where we are today and that there is a need to share power and space to rectify that. It would make things work better for everyone.

You just need to look at the audience of AAG [Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki] which is glaringly non-Pacific, and compare that with the way that rate payers – the institution’s funders – through the branding of the city are very proud to call themselves the biggest Pacific city in the world. There are huge problems there. How often are directors, curators and programmers reflecting on this history? Currently Pacific artists are the ones who are brought in to change the audience and bear the burden; told to “bring your people”. That’s just tokenistic and offensive.

NB: Well it passes over the responsibility to fix it, doesn’t it.

What I find interesting with my role here [Curator, Māori art, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki] is that I can be the agent to enact that change and so it’s the institution’s job to just get behind me and support that move and then walk with me as we progress it. So it’s complex, and it’s a mixture of the issues you mentioned, and it also relies on them being able to enter that space with me as opposed to me being the sacrificial Brownie. That has the power to be transformative and I am interested in that.

ET: And that’s the power of curatorship: you are always on that interface and speak on behalf of communities and you are that catalyst. We have the burdens and dynamics of the artist but in a different way.

I’m old enough to know that sometimes these concepts are fashionable….But there are also other terms that hold a lot of meaning and weight that don’t get discussed. Māori are still talking about sovereignty.

NB: Sometimes we talk about things being unfashionable. I’m old enough to know that sometimes these concepts [intersectionality, ally-ship, white fragility] are fashionable and are the latest buzzwords and ideas. But there are also other terms that hold a lot of meaning and weight that don’t get discussed. Māori are still talking about sovereignty: sovereignty is still the hot issue and tino rangatiratanga [self-determination, sovereignty, autonomy, power] is still central to unravelling all of this stuff.

ET: But it’s not as sexy is it?

NB: No not at all and there is this shallow perception that it has had its day in terms of a conversation, in the populist mind.

IGS: I wonder if, speaking as tauiwi working with indigenous people, I need to give up my own ideas of what is sexy and, instead, I need to privilege something beyond a slick exhibition. Maybe actually the be-all and end-all isn’t the best projection or sculpture but something else. Which isn’t to say that your exhibitions won’t be spectacular, but that something else takes…

NB: …precedence.

IGS: Yeah.

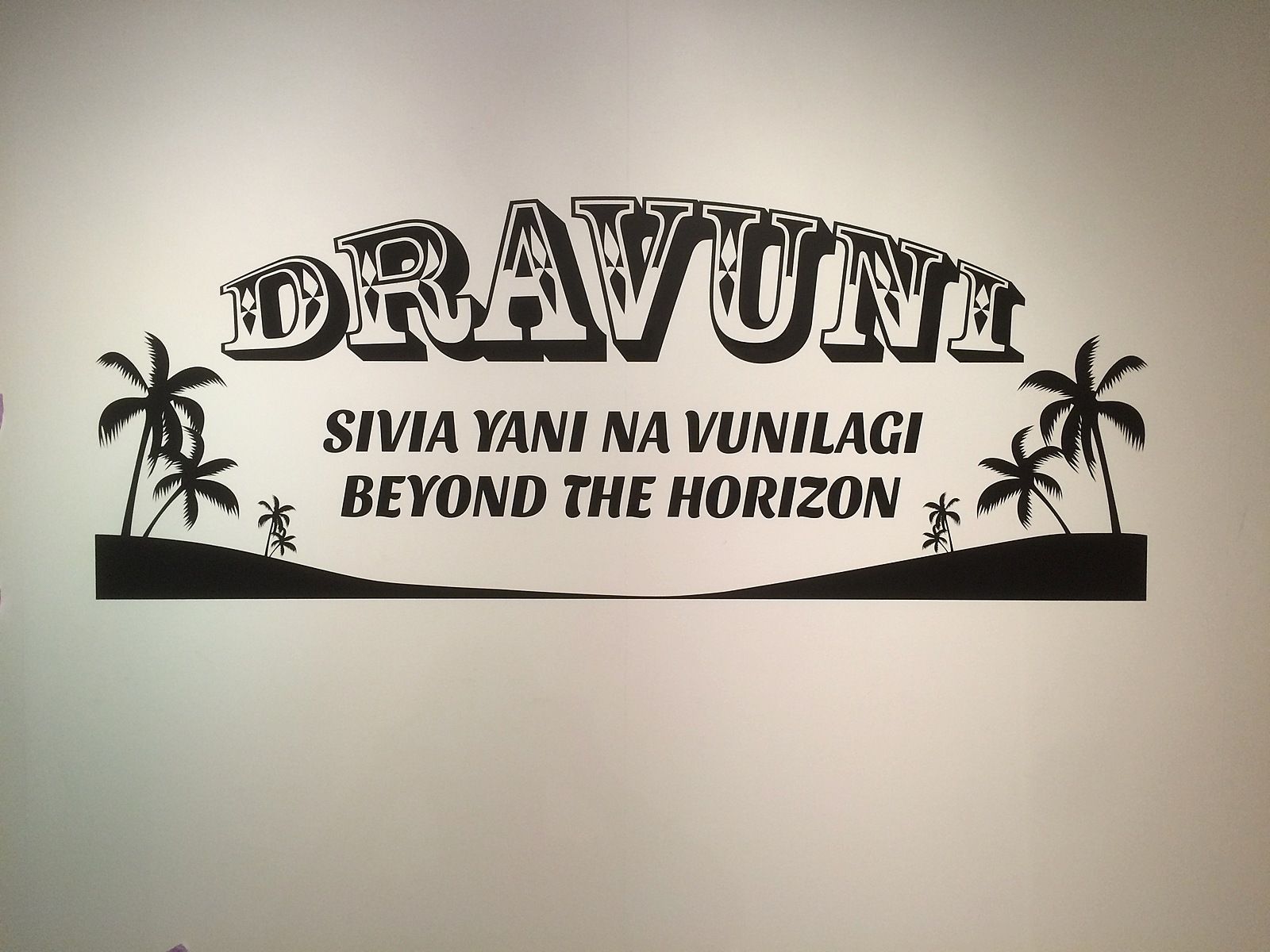

ET: I had that last year working with the New Zealand Maritime Museum. They asked me five months in advance to create a graphic for a show I was working on [Dravuni: Sivia yani na Vunilagi – Beyond the Horizon] and last minute an artist from my village came to me and said ‘aunty I want to design the mast head’. And I was like ‘okay.’ You have to know that the soul of my project was enabling my village to author the show. What he designed was very in line with a Fijian popular culture aesthetic which in a Western sense is very Wild West, like saloon style. The museum curator’s response was “What is that?”, and I just said, “We have to use it” and her response was that it was completely different to all the branding and again I just said, “We have to use it”. We went back and forth until breaking point: I just had to hit home how important it was. You know when I saw the graphic I had the same reaction [as the curator], but we just had to do it. And you know what? The aesthetic added so much value to the project, I loved it. I paid him for it, and valued him for his contribution and his work and that was the most important thing.

IGS: I think that’s great.

LL: I actually really liked that graphic, I thought it was really good.

I just want to pick up on something we have touched on and something that me and you [gesturing toward Ioana], have spoken about really briefly before and that’s the difference between equity and equality, and that giving a community one show isn’t the same as accurately representing them. In a lot of big institutions, we seem to see one cultural specific show over a 10 year period, so a 10 year programme would look like 2% insert-minority-culture-here and 98% dominant culture. But that has nothing to do with equity: maybe actually indigenous and other communities need to make the 98% bracket rather than the 2% bracket to make up for the fact that they are not used to seeing themselves in other places like mainstream media. So, to formulate that into a question, how do you think about equality and equity and the various communities you are having to serve all the time? How do you balance and negotiate these things within your programme, or do you at all?

I think about the burden that an indigenous exhibition has to bear in comparison to a Pākehā male artist show…

IGS: That’s something that stays in my mind a lot. I guess when I think about it, I think about the burden that an indigenous exhibition has to bear in comparison to a Pākehā male artist show, because you put that up and it’s easy, it’s breezy, people get it. Whereas you put on a show of an indigenous artist and it has all this proving to do; it has foundational layers that audiences need to get through before you get to the art, and I think that’s really shit and unfair. It devalues that work as the work of an artist and instead represents them as a cultural icon and puts weight on them to have to talk about cultural experience and who they are in Aotearoa. I think more shows is what we need to help normalise the foundations.

I just came back from the Honolulu Biennial where the works are allowed to just talk about their issues like climate change, or revisiting the history of Pearl Harbor, those types of things, and there is so much richness, complexity and an intellect that doesn’t get acknowledged if you continue to put up tokenistic shows that have to do all the work of all indigenous cultures within a single show.

In terms of my programming, I think there is a need for more indigenous shows, and there is so much good indigenous work that why would you not show more? Why are we restricting ourselves to unspoken quotas? The community warrants more shows and so I think about the equity thing not in relation to a programme within a year but within the context of Auckland, within the context of an audience’s logged memory.

NB: Maybe it’s healthy to reiterate with the artist that a show can be whatever they want it to be. Let them determine what the indigenous sphere is that they want to offer. The challenge to us is to maybe allow that to be and to advocate for the space they are trying to establish. Michael Parekowhai is an example of an artist who has a very specific way of articulating himself which encompasses his Māori and Pākehā heritage but is presented on his own terms and in a way that is accurate to him. That’s just one example, but it’s about us being confident enough to back their thinking and approach, and about making/broadening space for those ideas to be.

LL: So, I guess we’re saying then that good curatorship is allowing the artists to have their own agency and set their own terms for that?

IGS: Yes, but not just that. You can’t abdicate your responsibility and privilege as a curator. It’s not enough to say “take this space, it’s yours” and step back entirely. You’re still in it and your responsibility is to offer feedback whether it’s taken or not, but you’re not a bystander in that relationship. There’s a way to enable people to author things but to not leave them to be vulnerably alone.

The programming model of having indigenous shows and non-indigenous shows reflects the segregation of the community we live in, but it’s not the future.

ET: I have a contribution to that discussion but perhaps on a more advisory or governance level. The programming model of having indigenous shows and non-indigenous shows reflects the segregation of the community we live in, but it’s not the future. What Linda Tuhiwai-Smith talks about in terms of decolonisation is about acknowledging the indigenous presence, and that indigenous presence has to be in everything. It has to be in everything! Which is why in [the Tate travelling show] The Body Laid Bare, it astounds me, but doesn’t surprise me that this gallery [AAG] chooses not to have the presence of a Southern Hemisphere response to this theme. Because this exhibition has a profound potential to speak to broad audiences because every single work in there every single human can relate to. It’s such an important curatorial premise but this gallery has really lost an opportunity to broker a conversation and create a presence for the indigenous or non-Eurocentric voices. The presence of indigenous views has to be in everything and it’s not just curating; it’s who is on your board, who is making strategic decisions, who is programming. Indigenous presence and perspectives have to be at every level in order for there to be systemic change, and that’s the community I want to see.

So, indigenous shows here and there, and this salt-and-pepper approach which we have been living with for years is not moving us forward, and I wish things like the Lindauer show and the impact it had in bringing in a really broad non-traditional audience into this gallery was the thing that made AAG think, “how do we work more with these under-represented communities?” That’s the future. Putting money into a bus or into an outreach programme is not systemic change.

…with the Lindauer exhibition ironically it wasn’t a Māori artist but Māori subject matter which is hugely profound to Māori....It attracted the highest attendance numbers of a show in the new gallery space.

NB: Like Ema said, with the Lindauer exhibition ironically it wasn’t a Māori artist but Māori subject matter which is hugely profound to Māori, and that was the driver in the end for that show. It attracted the highest attendance numbers of a show in the new gallery space. I don’t think anyone anticipated that happening, myself included, but when I come in on a Saturday and I see a Māori male in his jandals and rugby shorts with his family looking at the portraits, looking at art, I really do need to take stock and be cognisant of what I am seeing and acknowledge the response that this show is recieving from the Māori community. I am concerned now about how I can have them return to the gallery. How do I get them back now that we have established that they know where the art gallery is?

IGS: I think Ema has hit it on the head. We are ready to move beyond just the programming and selecting of artists, and ask: how do we really imbue our spaces with an indigenous presence?

ET: It happens when you have well-informed leadership who commit to changing the way things are. This commitment is something which has to be made over generations to mana whenua and is something which is long term. It doesn’t feel like anywhere in Auckland has made this commitment long term, to say you know, “what are we going to do to change the game?” One organisation which is starting to talk a little bit in that direction – and I know this through my work with the Auckland Diversity Project for Creative New Zealand – is The Basement Theatre who are in a position where they are handing over power, doing things like handing FAFSWAG a four-show season for the year, because they know that that is changing the game. That comes from informed leadership.

NB: It comes from that idea of saying “yes, ok, we will share that ‘space’”.

ET: Yes, and [knowing that] there is mutual value in that.

NB: I’d really love to blue sky it, I think we don’t do that enough as Māori and indigenous people. We are reactionary and grappling with our current challenges and situations.

IGS: I feel as though that’s so interesting in how we all started this discussion, because none of us thought as though intersectionality is what we are doing because it is looking in the wrong direction ay? Because I hear what you are saying Nigel, and I think it’s all about working out the ideal world we want to be in and putting our energy there.

LL: But also, you can’t get there if that space isn’t given over first and we can’t give that space to ourselves.

ET: Well, we can create our own spaces.

LL: Exactly. So do you want to break into the spaces that exist or just create your own?

NB: To show my age, I liken it to the idea that we are all Neo in The Matrix, we’re all in the system trying to work it from the inside-out in different ways.

The model of Fresh was about relinquishing the power.

ET: Fresh Gallery Ōtara [which Ema established in 2006] is an exact example of that. It was a space which was safe, geographically disconnected. We created our own discourse that was about empowering all kinds of people to have a conversation about art, and over time the art world decided to come and have a look at what we were doing and it was a safe space for the art world too. The model of Fresh was about relinquishing the power. Manukau City Council didn’t know what they were doing in creating that space, but in the seven years that I was a manager there it created a parallel discourse and was a broker of two worlds. But we don’t have those kinds of spaces anymore.

We have the potential to foster these parallel worlds that are safe! So, what happens when we dislocate that conversation is that it has a completely different dynamic and I am really all about that dynamic. I’ll bring it into this institutional space, but the burden of this history is suffocating.

NB: Ema would talk about how her after-school kids would come and look at the shows at Fresh and give the most candid responses.

ET: And those after-schoolers were all informal. I am really proud of the fact that there were 10-year-olds in Otara – after I left – who had seen 50 shows and been a part of a conversation about 50 art exhibitions and met international artists and curators. And that’s what safety is.

NB: It’s an example still in 2017.

IGS: Yea, it would be good to have more models.

We rely too heavily on Western paradigms to orientate what we value and I know for a fact that we can park that now in 2017 and start centring our own ideas from Aotearoa and the Pacific that are timeless

Janet McAllister: Okay, I have one question which might be slightly too big to ask now but if you could sum it up that would be great. If we did do blue-sky thinking, what are the aspirations?

IGS: I actually have a really basic answer which is just that I want people to come into the space and feel comfortable. It comes back to ownership and somehow creating a space where everyone feels it.

NB: I want to change up the paradigms. We rely too heavily on Western paradigms to orientate what we value and I know for a fact that we can park that now in 2017 and start centring our own ideas from Aotearoa and the Pacific that are timeless and that we know are still true to our communities and start using those as ways of navigating and understanding. So, blue-sky to me is about turning it upside down and saying “is it still relevant?” It’s being able to critique what works and what doesn’t and allowing ourselves to have that conversation with each other because we don’t allow ourselves to look up there too often.

ET: I want to see every arts and culture institution having a social inclusion policy, I want every board to do cultural competency training, I think cultural safety needs to be a conversation we can apply and adapt to the arts and cultural sector. I would love to see a Pacific Island Director of Auckland Art Gallery, I want to see fair and equitable representation on all the bodies of strategic decision-making at Auckland Art Gallery, I want to see this gallery full of brown people mixing. Because art is the way that we foster intercultural understanding, and it’s not happening and it breaks my heart.

Editor’s Note: It has been pointed out to me that in allowing the conversation to move past intersectionality so quickly we failed to acknowledge the incredibly valuable mahi of Kimberlé Crenshaw in developing intersectionality theory. It was never our intention to dismiss her work which has been so pivotal in opening up the feminist discourse to include women of colour, us included.