The Call is Coming From Inside the House

What's up with all the childhood reboots?

If you do social media, you’ll probably have have seen a recent meme that goes something like:

For the record it’s 2015, but the white sans serif font over Robin Williams’ face (RIP) begs a good question: why are so many remakes coming out this year, and last year, and next year?

The answer, preached by a billion industry insiders, is that these things are profitable. You don’t have to take a risk on excellent but untested script x when you know for certain there’s a captive audience who’ll eat up whatever rebooted Spider Man excretion you feed them. It’s not even a particularly new phenomenon — take 1991 for example. Of the ten highest-grossing films to come out that year, one was ‘original’: City Slickers. The rest, from Terminator 2 and Beauty and the Beast to The Silence of the Lambs and Hook, were either sequels of recent films or adaptations of older source material.

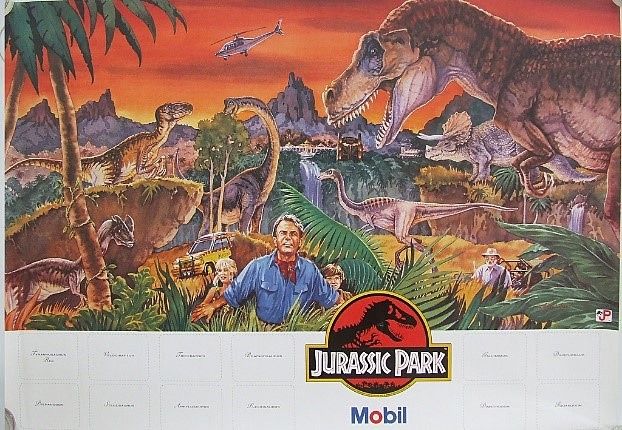

If you stare deeper at Williams’ scraggly beard, though, and the font superimposed thereon, you’ll see the question isn’t really “why are there so many reboots?” That answer is obvious – studios enjoy money. What Williams is really asking, is why, when I hear the Jurassic Park theme, do I remember a collectible wall poster and desperately trying to convince dad we needed more petrol immediately so we could swing past Mobil? Why, when I see Mad Max, do I recollect being allowed to stay up late and accidentally catch most of Return to Thunderdome? Why, when I'm told another Transformers film is being made, why do I think of energon cubes and shed a single tear? It’s not that there are fewer original films in 2015 than previous decades — it’s that all the remakes seem to be from shows or games we liked as seven year olds. It’s hard not to feel, well, infantilised. What Williams is really asking is: “why are there so many reboots of the cultural products that I loved growing up as a kid, between 1985 and 1995?”

I don’t have an answer, but I’ve got a theory.

To some extent, what gets rebooted is always a question of subject matter. The Andy Griffith Show and Leave it to Beaver were popular and influential — in the context of post-war America and its desperate fixation with the nuclear family. Stripped from that specific time and place, their plots are bizarre, borderline racist, and difficult for modern audiences to empathise with.

Other shows of the same vintage, though, have enough going on in them that we can look past their local peculiarities. Lost in Space, for example — a show about real men doing things while effete men scheme and women scream — nevertheless enjoyed global syndication up until recently, off the strength of the honestly exciting narrative that drove the plot: a lost family struggling to get home. Ditto Thunderbirds. Both franchises, and others quirky enough to maintain their cultural cred (The Flintstones, The Jetsons), have been made into films.

More recently, though, films are being rebooted that don’t seem to make sense outside the cultural milieu that gave rise to them. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, originally a parodic antidote to the gut-bustingly self-serious comics of the late 80s (Marvel’s Daredevil, Frank Millers Batman – itself a reboot) was last year made into the franchise’s second film in a decade. Rather than parodying the current run of action hero flicks, it embraced the genre. Transformers, famously invented to sell a line of toys, had nothing to hawk when Michael Bay brought their stupid explosions to the big screen. Why, then, are Hollywood studios producing what ought to be ‘risky’ films whose cultural roots we should’ve outgrown?

In film, as in politics and most everything else, you get to the bottom of perplexing questions by following the money:

Put another way —

The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), the organisation that promotes the studios' interests home and abroad, never used to mention international box office in its annual report. What happened in 2004 swatted away that complacency: since the late 90s, US domestic box office and international had been running virtually neck-and-neck, somewhere around $9-10bn each. In 2004, international box office exploded by an incredible 44%, to $15.7bn, leaving the US standing. It has continued on its strong upwards trajectory since, climbing to $21.2bn in 2010…

The fact that most films now make over two thirds of their revenue outside the US hasn’t escaped producers, and for the last couple of years there’s been debate on the impact this has on what’s produced. Should we expect to see fewer comedies because humour doesn’t translate well? Should we expect fewer films touting American-exceptionalism-as-deus-ex-machina (lookin at you, Independence Day)?

In fact, the Hollywood studio staple has for a while been the big budget extravaganza that will sell overseas. Content has been shaped accordingly. As David Hancock notes: “They’re making films that have fairly universal ideas and themes, they’re not really culturally specific.” A good example might be the recently released action film Fast & Furious 6 which has already hauled in almost twice as much revenue overseas as it has in the US.

Maybe. But globalisation’s responsible for more than ballooning profits: it changes how quickly we import and reconfigure cultural products from societies external to our own. Why does Teenage Ninja Mutant Turtles keep getting brought back from the dead? Because our generation was the first to watch it on TV after school at the same time as American kids were doing the same, at the same time as kids through a huge swathe of Western Europe were watching too. We’re the first generation thoroughly enough globalised that it makes economic sense to produce blockbuster cultural products aimed at a niche viewership.

Or, to put it more like an Excel spreadsheet:

The previous material doesn't even have to be great in order to get a reboot green light, because "the majority of sales will come from international markets." Global audiences are "still hungry" for reboots, and it shows in box office figures, even if American audiences get weary of ceaseless Transformers films.

Even if only 5% of kids who grew up watching heroes in a half-shell are still interested, studios know that’s not just 5% of US audiences: it’s also 5% of the much bigger OECD. Chinese and Russian audiences — the biggest emerging cinema markets — don’t baulk at consuming Western cultural products, and as they catch up we can expect the strip-mining of nostalgia to become even more frenetic, the pace of franchise reclamation so frenzied that shows won’t even go off-air before being rebooted for the big screen. We shouldn’t expect it to stop with movies either, for better or worse.

I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with films inspired by misplaced wistfulness and bucket loads of cash. So long as they make audiences think and feel new things, it should be hard to distinguish them from ‘original’ material (and what is ‘original’, anyway?). It reminds me of the supposed difference between travelling and tourism:

Travel enables us to see our own culture more clearly, by contrasting it against others. And here we must make a distinction between travel, which takes the traveller out of his or her comfort zone, and tourism, which strives to maximize comfort and familiarity in a foreign setting. A good travel experience is not relaxing, but stimulating and taxing. The senses are on full alert. The mind struggles to keep up with the bombardment of unfamiliar data, the linguistic difficulties, the puzzles and queries and possible threats.

When childhood nostalgia is repackaged and sold back to us, the past becomes less a foreign country than a two week bender in Bali. That’s not to say our entertainment always needs to be challenging or highbrow, or that there haven’t been some truly excellent remakes; but for every Lego Movie or Fury Road, there are three appalling Transformer films and four execrable X-Mens, and I love CGI Arnie as much as the next fully adult snake person millennial, but for the same cost we could’ve had ten more It Follows’s.

As ever, if we want fewer childhood-damaging shitshows retroactively ruining after-school TV, we’ll need to vote with our wallets, take a breath, and admit that a 21st century 3D NeverEnding Story is an overwhelmingly terrible idea.

Anyway I saw Jurassic World last week. It was rad.