The Basic Work of Writing: An Interview with Nicky Hager

Matt Harnett talks to Nicky Hager on mass media, democracy, technology and publishing.

Nicky Hager is a prophet of radical transparency. As New Zealand's most lauded, reviled and feared investigative journalist, he doesn't simply advocate open democracy – he chases it down labyrinthine, bureaucratic corridors, and drags it kicking into the light.

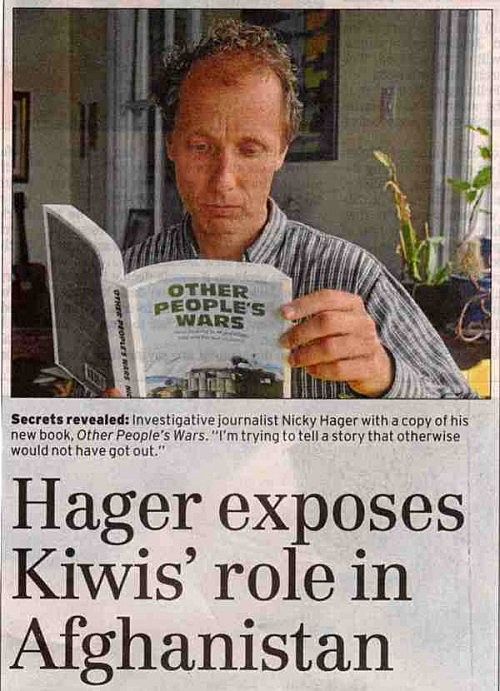

His most recent book — 2011’s Other People’s Wars, which detailed New Zealand’s involvement in Afghanistan — was met by horrified disbelief by the public, and disbelief of another sort by Prime Minister John Key: “I don't have time to read fiction... nothing surprises me when it comes to Hager.” Presumably the Prime Minister did not mean to suggest the revelations in Hager’s previous book, The Hollow Men, which meticulously scrutinized the entrenched cynicism, cronyism and the abiding distrust of the public by National Party insiders, came as no surprise. That book, published in 2006,was at least partially responsible for then-leader Don Brash stepping down – and in so doing, creating a direct path for Key’s own ascendency.

According to John Pilger, Hager is one of the world’s best investigative journalists. According to David Farrar, he "needs to get out more." According to Deborah Coddington, he’s a "John Minto-adoring surrender monkey" (actual quote, honest).

According to me, he delivered an excellent public lecture last week, the latest in an outstanding series put on by the Bruce Jesson Foundation. It was an optimistic talk, suggesting that in an age of a million op-eds and corporate interests and public relations firms, the fine art of investigation – of bringing to light that which powerful interests want kept from public scrutiny – one doesn't need a degree in journalism to make a difference. One simply needs tenacity, and to give a fuck.

In the responses you had to questions posed by the audience after your talk last week, you mentioned the importance of the mass media as a way of keeping citizens informed about things going on in their democracies. You said they were important in a way that fragmented internet sources could never really be. Could you go into a little more detail on that?

It’s easy to look at the quality of some mainstream media and think, ‘well, good riddance.’ But I think that would be a terrible mistake. First of all, there is nothing on the internet that has shown a sign of replacing the basic, daily provision of news, as opposed to the provision of comment, which blogs and things do. The other thing is the internet is an extremely siloed place. We’d be a completely different society if the left-leaning people went to one site, and the right-leaning people went to another, and people who were interested in sport went to a place that didn’t have any politics at all, and so on, and people weren’t seeing the same stuff. That, to me, is quite separate from what we might say about the quality of mass media. There’s a huge value in people seeing the same stuff – people knowing what is happening with that building down the road? And how did the Prime Minister defend themselves when someone said such-and-such, and all that daily business that binds us together in being a society. The internet shows no signs of replacing that – in fact, the opposite. That’s why I'm a strong advocate for publicly-funded but independent news media, of a mass-media type. It’s the most hopeful economic model for the future of media.

It’s easy to look at the quality of some mainstream media and think, ‘well, good riddance.’ But I think that would be a terrible mistake.

Do you think the kind of system we've got in New Zealand, where we've got state-owned enterprises —

I think that’s an abomination. In a way it’s almost the worst model you could have. What we need is a really strong statutory independence. People who think that a public media will inevitably bend to the government are not remembering that we also have, for example, the courts, and we have institutions of government, like the ombudsmen and auditor general, who can be a huge pain to the government, but still have their independence. Something like that is needed.

I get the impression you’re saying that the fourth estate should be similar to the judiciary in a modern democracy — sacrosanct, on some other level.

We know that, but we leave it in the hands of private organizations. The way that this has become acute is with the increasing public use of the internet; the competition for the news media is not between the New Zealand Herald and TV3, it’s between the New Zealand Herald and Facebook, and TradeMe, and YouTube, which can take advertising which once was monopolised by the media. Two things happen: one is that the advertising isn’t there, and the other is that you get people who measure the clicks on stories in their news organizations and get into a competitive entertainment mode, rather than a news media mode.

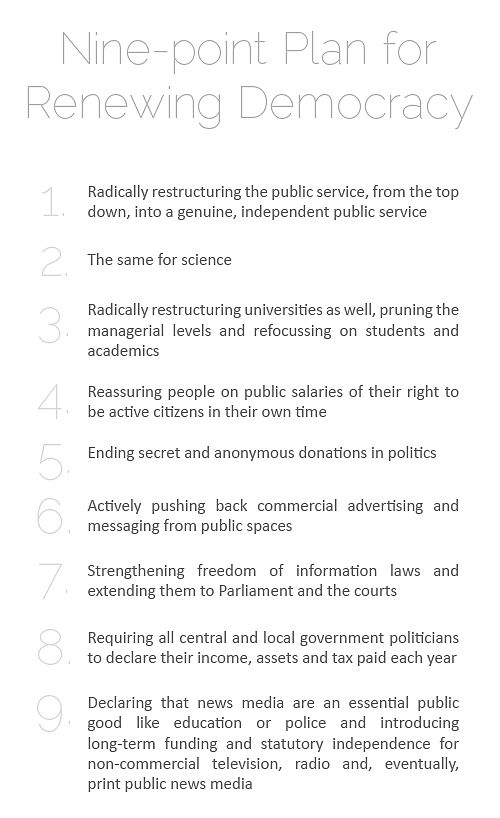

That reminds me of the nine point plan you mentioned during your talk, for renewing a faltering democracy. I found it interesting because a lot of people mention ways in which democracy seems to be failing under the stresses of modern life and the various technological and ideological impositions we’ve put on it, but you’ve suggested nine things you think might improve our functioning as citizens. Two that particularly I found interesting were public services and the sciences.

My first job when I left university was working for something called the DSIR – the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. It was a public interest science organization, fully funded by the government. Its job was to provide science that a nation like New Zealand needed. There were people there inventing plastics and polymers, people looking at ways to improve soil agriculture, people looking at fresh-water fish – a whole range of science according to different categories of what a country like ours needs.

One of the parts of the free-market reforms that happened in the ‘90s under National was semi-privatizing the way science happened. That meant requiring much higher proportions of private funding. If you’re NIWA – the organization that looks at fishing – a lot of your funding is coming from the fishing industry, with its priorities and its pressures, whereas it should be coming from the public and therefore influenced in terms of what the public thinks are the main issues of importance. Conservation of resources in the sea, for example. Because these organizations were competing for private money, it became harder for the scientists themselves to be independent; in other words, to speak out in public, to write what they want, to be critical of policy, because this had commercial implications for their institutes. If you were an institute which was dealing with the farming industry and someone was writing things about the damage the dairy industry is doing, you might not get as much funding. Most people won’t know this but it actually matters hugely to a country.

This seems like such an obvious conclusion; why did these changes take place?

They took place because everything in New Zealand was suddenly being interpreted through the free-market ideology, which is, when you step back from it, almost ludicrous. It’s a theory that the most important thing in the world is making money, that people are only motivated by money, that the things that matter in a society are the things that can be measured by money, that if they can’t be measured by money they’re probably not important. Now, we all know – nearly everyone knows –that’s ludicrous. But it was the ideology that dominated a lot of New Zealand politics for the best part of 20 years, nearly a generation. Times change. New Zealand has moved on from that. We now know that leaky buildings were a monument to the insanity of deregulating the building sector – Pike River was a monument to the foolishness of saying ‘you don’t need the stupid nanny state government interfering with everyone’ and so you cut back on mining inspectors and so on. We now know that was stupid.

You mentioned as well the strengthening of freedom of information laws, and extending them to Parliament and the courts. How far do they extend currently, and where would you like to see them?

At the moment we have in most ways a fantastic freedom of information bill, the Official Information Act, that covers virtually every government agency, from the Cabinet office down to the primary school. It’s a very good piece of law and it’s very broad in that you can ask any question you like, any category of information. But what I've watched since I started to use it, not long after it was passed in the ‘80s, is that the people who don’t want to let information out – growing numbers of PR people – they've got good at getting around it. It’s like a 30-year-old tax law – every lawyer knows how to get around it by now. The OIA works, but in the kind of work that I do, which is where you’re trying to find out something which is embarrassing or they’d rather didn't come out, or is going to show something which they’d rather wasn't shown yet – they’re very good at stopping it, which is why I spend quite a lot of time writing official information requests, but even more time finding inside sources.

So what do I think? I think the OIA needs to be reviewed and re-written with freedom of information as the goal. There have been a couple of reviews through the years, which have not had freedom of information as the goal, they've been about narrowing and restricting, but it needs to go in the opposite direction. The other thing I mentioned in that talk was that it hasn't stretched through everywhere. For example, it doesn't cover Parliament. It’s a curious thing, because why shouldn't someone be able to write and say how does the Green Party or the ACT Party or whatever spend their money? How much money are they given?

So… there’s no way currently of finding that out?

No. It is utterly, totally impregnable at the moment.

That seems incredible.

It is incredible, because it’s at moments like that you realise what transparency is for. If people reasonably believe that no one will ever, ever, ever be able to find out how they spent their Parliamentary expenses, then it’s a temptation for some people to do things which they wouldn’t if they knew nosy journalists would be putting in a routine request for them later that year. It’s so obvious, but politicians make the laws, of course; to date they haven’t been willing to do something which they’ve seen as inconvenient and causing themselves problems. The other area is the courts. I think we have wonderfully independent and admirable courts, but one case when they’re a pain is that they live slightly in the dark ages when it comes to official information. If you want to ask for information which has been in a court case, or evidence which has been provided, there is no routine statutory process where it has to be provided within a certain time. It might take months, you might not get a reply, they might say no without any reason, and so it would just be a good area to clean up.

A lot of people, when starting a big research project, encounter that first fuck-up moment - where they realise they've done something disastrously wrong. Has this happened to you?

With the kind of work I do, I'm trying to tackle big, difficult research subjects. People see the ones that work, but they don’t see the ones that don’t. No one’s ever going to criticize you or say you’re wrong for something that you don’t publish. For example, I spent many months working on a script for a film about media issues in Palestine and Israel, which never saw the light of day, and that was to do with funding problems and internal problems with the team I was working with. I suppose the lesson for me from that was when you work on a project, work with people you’re sure of, and who you totally respect, because you’re going to have to go through a whole lot of things together. That’s a lesson I tend to enforce fairly strongly in my own life, because it’s such a terrible thing to waste time.

I guess doing long-form investigations, as you do, it’s mostly a solitary job, being the person who pulls all the threads together.

It’s a very solitary job, but it’s not like working on my own, because I spend all my time meeting people, asking people for help, building trust with people, having really good relationships with people. It’s solitary in the sense that in the end, I have to do the work, and you can’t expect anyone else to do that. These are projects which often are measured in hundreds, thousands of hours, and that’s an interesting thing I’ve learnt, which is you get an instinct, a sense, of how big something is. There are some projects that are definitely viable, but they’re not going to work with a quick poke, with a week’s work or a few phone calls. So it’s a matter of ‘Is this worth hundreds of hours, or not?’ Because that’s what it’ll take to do it properly.

How do you measure that worth — do you balance the good that the public’s going to get out of it, versus the amount of time you’re going to need to put into it?

Pretty much, actually, yes. If I’ve worked on a subject before, then I’ve got a greater efficiency at doing it, because I’ve already got contacts and my instincts are telling me if I’m going in the right direction. But in the end the main thing is the value of it. For example, at the moment I’m working on a very large project, a completely new area, which is about finance, and I started from a low base of experience and competence, but that’s also part of the fun of it.

Sure, discovering an entirely new realm of information that you knew nothing about. I was wondering about your publishing endeavours. Was your writing and publishing process for Secret Power in ’96 the same as it has been for your latest, last year? What’s changed, in terms of your process and how you’ve gone about it?

My publishing story is almost like a cliché. With my first book, which would eventually have more publicity than everything else I’ll do in my life probably, around the world, and numerous documentaries made of it, translated to other languages and all kinds of things – when I tried to get a publisher for it, nobody was interested! It was really hard, and if I hadn’t already spent so much work on it, it would have been possible to believe people, that it didn’t have value. But actually I think it’s just the nature of publishing. Publishers get approached by numerous people, and they’re only going to accept a few of those books, so they spend their lives turning people away. I think the publishers I approached flicked their eyes over it, saw some acronyms, it looked a little bit difficult, and they turned me down without reading it. I think that probably happens to lots of people, and it’s terribly hard, and it’s also terribly unfair, because when you have been published it suddenly gets so much easier.

Because you become more bankable, I suppose.

It becomes a more reliable economic bet. What happened in my case was I got turned down by various publishers, and then I remembered that I had some old friends from university, who’d gone on and set up a publishing company. It wasn’t that kind of publishing company – it was producing books on nature photographs and calendars for tourists, and things like that, which meant it wasn’t an obvious choice. But when I took it to them, they were old friends and we’ve enjoyed working together on all my books since.

When you were first pitching your book, how did you try to convince these people that you were seriously willing to put in the time to research it? Had you already written it?

This is something I’ve done with all my projects. I haven’t written an outline and tried to pitch it like that to publishers, because my own view is that the main obstacle in a large projects is ourselves, and that the hardest thing is get it up to my own standards, not someone else’s. In every case so far, I have completely written it to my satisfaction before I’ve shown it to someone else.

That must take quite a toll – obviously there’s no advance or anything, so you’re basically working full time without pay. How do you support yourself, between projects?

I live in a small country where there are no big foundations or sources of funds. When I started off, I used to be a builder at the same time, and I would support myself with part-time building. As I’ve done it more, I’ve got my royalties, but when I’m going for years in pursuit of a book, sometimes I’m supported by old friends, who just donate me money. There’s a principle to this: in a country like New Zealand, it should be that looking at the economics, we should have pretty well no authors – or one or two – no musicians, no artists… In a country like this, with a low population, people find one-off ways to do things. Every author in the country is finding their one-off way that they can support themselves. Through part-time work, or whatever it is, we all find different ways of doing that because otherwise you just can’t do it in a small country.

Do you think that sort of ethic serves us better as this new technological transition starts to hit the publishing industry – do you think we’re almost prepared for that, because that’s how we’ve always had to do it, on an ad-hoc basis?

I think it does make people more flexible. I think for people in the countries where they’ve had fantastic funding sources, you’re right.

I notice when you write smaller investigative features, you tend to publish them in the Sunday Star-Times. Is that a case of it being a very accessible, general broadsheet? So it’s one of those un-siloed places, where everyone can get their news?

I’m happy to write for the SST because I want to reach a wide audience, you’re correct. There are other options, but it’s a really good one. I owe a lot thanks to the editor, Cate Brett, who used to be there. I arrived there without a journalism degree. I’d written books, but I didn’t have a degree. I wasn’t a ‘normal’ journalist, and yet she was prepared to take my work on its quality, so I’ve been happy to stick with them for that reason as well.

How, in general, has the evolution of technology changed the way you investigate stories?

Of course it’s changed everything... well, certain things it hasn’t changed. People imagine you can go out into the internet and find whatever you want, because there’s so much stuff. Sometimes it’s true – there are remarkable resources, of course; once upon a time, before you had search engines, there might be information somewhere out in the world, but the chances of you knowing it was there and finding it were remote. Now you put search terms in and can find the obscurest source, so it is a wonderful new resource for connecting the one person who wants the information with the one person who might have it. But it would be a terrible mistake to think that all information is on the internet, because most isn’t. Most of the information that I want isn’t.

Sure.

While I’ll go there for clues and endless ways of finding things quickly, the old-fashioned ways of doing things are almost more important than ever. One of the important disciplines in my work is gathering little bits of information. If I hear something on the news, or I meet someone who knows something, I carefully make a note of it, and put the date on top of a piece of paper, and I stick it in a file, because those little bits are sometimes crucial to a story a couple of years later. The fact is that the internet has made it easier to get to information, but there are industries of people whose job it is to keep information in; to not let it out. To make sure that what’s on the website is sanitised. That’s where the work of talking to people is still essential.

The fact is that the internet has made it easier to get to information, but there are industries of people whose job it is to keep information in; to not let it out.

So you’ve found that although the way might access information has changed, your actual methodology in putting a story together hasn’t changed terribly much?

No, it hasn’t changed because the steps are about the logic of ideas and information. First of all I read broadly, whether on the internet or not, just to get the lie of the land. That’s an essential first step, because otherwise you don’t know enough about what you’re looking for, and what the right questions are. Then there’s this thing that’s special to investigative journalism, which is then strategizing – thinking: this is the question I’m trying to answer, what are the places in the world where the information is going to be? And the first thought is, If it’s a secret, it’ll be nowhere. And the second thought is, Well there’ll be the people who work there, and there are people in allied places, and there are the formal workers, and of course there are families of these people, and there are lawyers, and then there are the places where they went to university… it always stretches out, and out, and out, and what seems like nothing then gradually works its way out. Those steps are the same whether or not you find lots of stuff online. Then of course, the basic work of writing.

Entitled ‘Investigative Journalism in the Age of Media Meltdown,’ Hager’s talk from last week can be downloaded in its entirety here (.pdf).