Ten Articles That Defined My Year

I struggle with Top Tens. The prospect of whittling down an entire year - most of which I’ve already forgotten or repressed - into a neatly packaged list makes me nervous. Thankfully, the prospect of rambling self-indulgently about myself doesn’t, so here are ten articles that defined my year:

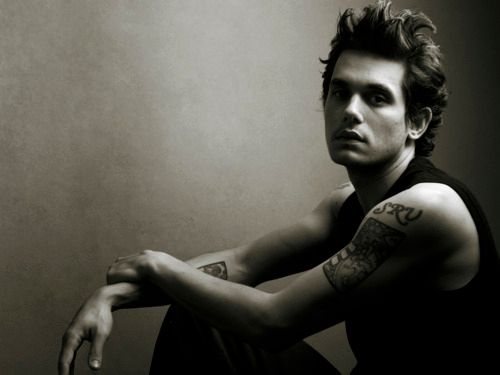

John Mayer: Playboy Interview by Rob Tannenbaum | Playboy (February, 2010)

I converted to J.C. Mayer in March on account of his interviews with Vulture and Playboy. It was so refreshing to read him. He was so frank, so fascinating and, best of all, so fucked up.

PLAYBOY: Do black women throw themselves at you?

MAYER: I don’t think I open myself to it. My dick is sort of like a white supremacist. I’ve got a Benetton heart and a fuckin’ David Duke cock.

It takes a lot of courage to be this open about yourself, to embrace yourself like this, and this is what I liked about him.

MAYER: I have to explain this so people don’t say, “Sure, you’re 32, and you want to fuck other chicks.” … It’s not like I wanted to be with somebody else. I want to be with myself, still, and lie in bed only with the infinite unknown. That’s 32, man.

MAYER: Here’s what I really want to do at 32: fuck a girl and then, as she’s sleeping in bed, make breakfast for her. So she’s like, “What? You gave me five vaginal orgasms last night, and you’re making me a spinach omelet? You are the shit!” So she says, “I love this guy.” I say, “I love this girl loving me.” And then we have a problem. Because that entails instant relationship. I’m already playing house. And when I lose interest she’s going to say, “Why would you do that if you didn’t want to stick with me?”

PLAYBOY: Why do you do it?

MAYER: Because I want to show her I’m not like every other guy. Because I hate other men. When I’m fucking you, I’m trying to fuck every man who’s ever fucked you, but in his ass, so you’ll say “No one’s ever done that to me in bed.”

I hit peak-Mayer when he came earlier this year - a friend was opening for him and called the morning of the gig asking if I wanted to come. It was horrible timing: work had been mental and I’d been getting about three hours sleep a night. I was so exhausted I said no. Man oh man, what was I thinking. Those were some dark days.

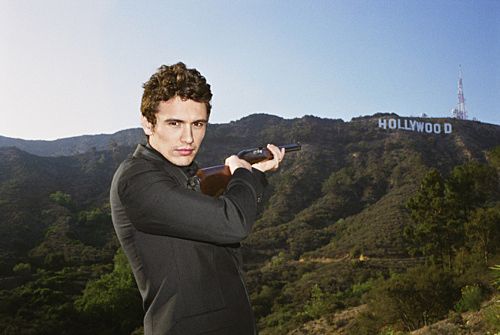

The James Franco Project by Sam Anderson | New York Magazine (July 25, 2010)

Anderson’s profile is a great read, but what’s even greater is Franco himself. This is what I like about him: he’s living the absurd life. In The Myth of Sisphyus, Camus proposes - to put it simplistically - that what counts isn’t the best living but the most living. This is Franco.

"Take, for instance, graduate school. As soon as Franco finished at UCLA, he moved to New York and enrolled in four of them: NYU for filmmaking, Columbia for fiction writing, Brooklyn College for fiction writing, and—just for good measure—a low-residency poetry program at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina. This fall, at 32, before he’s even done with all of these, he’ll be starting at Yale, for a Ph.D. in English, and also at the Rhode Island School of Design."

"Short stories he worked on at Columbia and Brooklyn College were published in Esquire and McSweeney’s. His NYU student films—including the artsy adaptations of poetry he was telling me about in the bathroom—graced all the major film festivals. His documentary Saturday Night, which began life as a seven-minute NYU assignment, blossomed—thanks to unprecedented behind-the-scenes access to SNL (a show Franco has hosted twice)—into a full-length feature."

In this sense, it doesn’t matter if his work is average, what matters is that he’s doing everything he wants to be doing.

What Is It About 20-Somethings? by Robin Marantz Henig | NY Times (August 18, 2010)

Franco came at a point in my life when I was experiencing a paralysing sense of panic about the future, about the choices I needed to be making but wasn’t, and Robin Marantz Henig’s piece in the New York Times captures this terror perfectly:

The 20s are like the stem cell of human development, the pluripotent moment when any of several outcomes is possible. Decisions and actions during this time have lasting ramifications. The 20s are when most people accumulate almost all of their formal education; when most people meet their future spouses and the friends they will keep; when most people start on the careers that they will stay with for many years. This is when adventures, experiments, travels, relationships are embarked on with an abandon that probably will not happen again.

Just as adolescence has its particular psychological profile, Arnett says, so does emerging adulthood: identity exploration, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between and a rather poetic characteristic he calls “a sense of possibilities.” A few of these, especially identity exploration, are part of adolescence too, but they take on new depth and urgency in the 20s. The stakes are higher when people are approaching the age when options tend to close off and lifelong commitments must be made. Arnett calls it “the age 30 deadline.”

Those three articles chart the psychological headspace I was in this year. The rest are just excellent reads:

Roger Ebert: The Essential Man by Chris Jones | Esquire (March, 2010)

Hands down the best profile I read this year. Chris Jones is amazing.

The Jonathan Franzen Award for Jaw-Dropping Literary Genius Goes to… Jonathan Franzen by Chuck Klosterman | GQ (December, 2010)

Despite being suspiciously overhyped, Freedom is one of the greatest novels of our time. One of the things I loved about it was the way it jumped back and forth with such ease, and how this narrative structure emphasised that aside from being about personal liberties, the book is also about freedom at a much more fundamental level: it’s about psychological freedom and the fact that we’re inevitably tied to our past, our present, our future. Our wives, our husbands, our parents, our children. Our dreams. Our mistakes. We may be free, but we can’t escape.

The Time Magazine piece on Franzen was a bit gross. I wouldn’t recommend it. Chuck Klosterman’s profile, though fanboyish at times, is heaps better.

No Secrets by Raffi Khatchadourian | The New Yorker (June 7, 2010)

It’ll be interesting to see how the WikiLeaks saga plays out since the way the U.S. government has handled it so far has been disgusting (though, let’s face it, unsurprising). What happens from here will be particularly important for the future of journalism. While I don’t advocate complete transparency, WikiLeaks has the potential to revitalise journalistic practices and facilitate democratic expression, and this is clear in Khatchadourian’s intimate profile of Julian Assange which documents the preparation and release of Collateral Murder earlier this year.

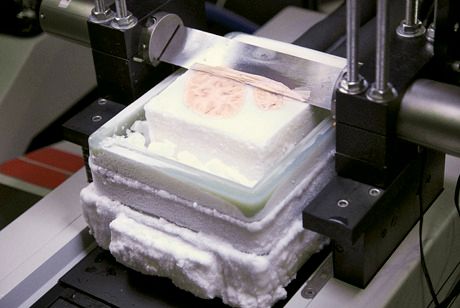

The Brain That Changed Everything by Luke Dittrich | Esquire (October 25, 2010)

In 1953, Dr William Scoville operated on an epileptic patient, H.M., removing both his left and right medial temporal lobes. Although the surgery successfully treated his epilepsy, it also destroyed his ability to form new memories. In the years since, the study of H.M. has contributed considerably to our understanding of the human memory system and the neural basis of these processes.

I can’t remember what I was doing the day H.M. died, though I do remember what a huge deal it was. A year later, they started slicing up his brain at The University of California. Luke Dittrich - Dr Scoville’s grandson - weaves together this momentous event with the lives of H.M. and his grandfather, making for a captivating read.

The Shadow Scholar by Ed Dante | The Chronicle of Higher Education (November 12, 2010)

An amazing piece written by a man who makes a living writing custom essays - and in some cases, entire theses - for graduate students.

The Great Cyberheist by James Verini | NY Times (November 10, 2010)

I’m a sucker for a good heist, and James Verini’s account of Albert Gonzalez’s exploits - acting as an informant for the Secret Service while masterminding the biggest credit card fraud in history - is spectacular.

What Was the Hipster? by Mark Greif | New York Magazine (October 24, 2010):

It always interested me how hipsterdom seemed not only undefinable, but something noone actually wanted to affiliate themselves with. Douglas Haddow’s Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization and Christian Lorentzen’s Why The Hipster Must Die (both excellent, damning reads) captured this beautifully, and What Was the Hipster? bookends this discussion with an insightful overview of the trajectory of this cultural zeitgeist:

The hipster is that person, overlapping with the intentional dropout or the unintentionally declassed individual—the neo-bohemian, the vegan or bicyclist or skatepunk, the would-be blue-collar or postracial twentysomething, the starving artist or graduate student—who in fact aligns himself both with rebel subculture and with the dominant class, and thus opens up a poisonous conduit between the two.

Indeed, the White Hipster—the style that suddenly emerged in 1999—inverted Broyard’s model to particularly unpleasant effect…As the White Negro had once fetishized blackness, the White Hipster fetishized the violence, instinctiveness, and rebelliousness of lower-middle-class “white trash.”

Suddenly, the hipster transformed. Most succinctly—though this is too simple—it began to seem that a “green” hipster had succeeded the white. Certainly the points of reference shifted from midwestern suburbs to animals, wilderness, plus the occasional Native American. Best perhaps to call this the Hipster Primitive, for linked to the Edenic nature-as-playground motif was a fascination with early-eighties computer electronics and other rudimentary or superannuated technologies.

One could say, exaggerating only slightly, that the hipster moment did not produce artists, but tattoo artists… It did not produce photographers, but snapshot and party photographers… It did not produce painters, but graphic designers. It did not yield a great literature, but it made good use of fonts.

Special Mention: Eleven Lives by Tom Junod | Esquire (August 16, 2010)

Tom Junod writes with exquisite rhythm, and his coverage of the eleven men who died on the Deepwater Horizon serves as a reminder that it wasn’t just the pelicans who suffered.