Summer Reading: Our Favourites From 2015

Our fantastic contributors on the best things they read last year

“Each year around 50,000 people die in New York, and each year the mortality rate seems to graze a new low, with people living healthier and longer. A great majority of the deceased have relatives and friends who soon learn of their passing and tearfully assemble at their funeral. A reverent death notice appears. Sympathy cards accumulate. When the celebrated die or there is some heart-rending killing of the innocent, the entire city might weep.

A much tinier number die alone in unwatched struggles. No one collects their bodies. No one mourns the conclusion of a life. They are just a name added to the death tables. In the year 2014, George Bell, age 72, was among those names.”

In his nearly 40 years at The New York Times, journalist N. R. Kleinfeld, has developed a skill for writing remarkable pieces which ensnare your interest until the very last full stop. Last year he wrote a piece about George Bell, an isolated New Yorker who died alone and was only discovered when neighbours reported a bad smell issuing from his apartment. It’s a awe-inspiring example of journalism that stays with you long after its conclusion.

Opening with the harsh details, we first learn of George Bell as a corpse, an unnamed body deformed by decomposition, and through the process of attempts to identify him, Kleinfeld drops little details about who Bell was until, at the end of the piece he writes his own respectful epitaph to Bell’s life, relationships, and passing.

Over the course of the article the reader meets the two investigators charged with the task of going into Bell’s flat, we learn how they have been impacted on by their profession and how the prevalence of such deaths has changed the way they have lived their own lives. We also meet a Christian undertaker who reflects on the unmourned deaths he encounters and his desire to see each burial or cremation treated with respect.

This piece of journalism shows the importance of detail in writing, and significance of every word to impart unique power. Each sentence in this article lays against the next growing the work organically, binding the reader to its narrative.

"The Lonely Death of George Bell" is a piece of journalism my friends are no doubt weary of hearing about by now, but I persist on getting anyone I know to read it anyway: in my mind it is a perfect, written with factual basing and an empathetic heart. Not only does this piece inspire my own writing, it continues to remind me of the other lonely George Bell’s who exist around me, and the importance of community.

Proof that sweeping condemnations of New Zealand journalism are undeserved. The media industry—it’s true—is collapsing, cleaving, reconstituting. But there are still fine journalists out there, doing fine journalism.

Peter Newport’s interview with Carrick Graham (and others), "Carrick Graham: Without Apologies" found a new angle on the Dirty Politics juggernaut. Graham presented himself as a modern-day Machiavelli, a professional in the dark arts of politics. But, as with Machiavelli, his candour begs a question: If these shadowy figures are so Machiavellian, why do they reveal the tricks of their trade? Why not keep their secrets secret?

Marcel Merleau-Ponty took Machiavelli’s transparency to be a sign of public-mindedness. By flattering princes, he provided cover for his whistle-blowing, for his humanist concern to teach the public how they were being played.

How are we to interpret Graham’s motives? Was this a back-handed gift to our democracy? Or an enticement to his “adversaries” to become more adversarial? Or were his motives simpler still? Read and be the judge—and discover something sour about New Zealand's politics along the way.

The essay that shook me up the most last year was Ailish Hopper’s Boston Review piece, “Can a Poem Listen?: Variations on Being-White.” In prose that is sensitive and beautiful and measured, Hopper unpacks the limitations of white poets who write about whiteness. “Are we writing race and racism, reinforcing the white viewpoint, which is designed not to threaten its own power?” she asks. "Or, are we rewriting race and racism, not merely representing, but disturbing; showing not just whiteness—but what it is to be awake, and disruptive, inside it?"

The dominant tropes that poets tend to use— “My guilt is so heavy, I don’t know even know what to say” or “Hey, look! I am suffering what you are suffering” — fail to challenge the dominant white viewpoint, because they protect the writers from the censure and disapproval of the very structures of power that they lament, and from which they claim to dissociate. It is easy and comfortable to express liberal guilt. It is difficult and uncomfortable, but necessary, to claim your participation in the habits and effects of structural racism.

White poets writing about race, Hopper claims, have a responsibility to put themselves “within range of white power’s whip”: to risk writing uncomfortable poems, poems that anthologists will not want to publish, that presses will not want to touch; poems that articulate the disturbing judgements, reactions, and thought patterns of white power and structural racism that we whitefellas are fed along with our mothers milk. This was a threshold concept for me, and I’m still reeling from it.

I thought this Jared Savage piece, ‘How We Raised A Killer’ was super important for humanising and complicating a crime story that had seen some pretty sensationalist reporting. Savage looked into the background of the 13-year-old convicted of manslaughter for killing Arun Kumar. I remember reading the piece and having to keep shutting my eyes in disbelief. You cannot finish that article without being chilled by the number of times that child was failed by both the adults around him and the state services that should have protected him. It's a long and careful piece, and it's super-aware of the Herald's wide-ranging audience. We need to loudly and enthusiastically celebrate good journalism like this when we see it, especially when we see it in the Herald.

My runner-up (that has appeared - syndicated - on the Herald site too) would be Alex Casey’s strident defence of Chrystal Chenery, originally published on The Spinoff.

In 2014, Eli Saslow of The Washington Post won a Pulitzer for his work chronicling America’s hungriest citizens, and the entrenched power structures that keep them that way. At the end of last year, he wrote another piece I found captivating, and again one that touched on a perennial American problem: mass shootings. Rather than talk about the politics or the shooter or even guns, Saslow follows a girl, Cheyeanne, who was shot, and her relationship with her mother, who cares for her:

“The thing I keep thinking about is how that bastard stepped on me,” she said.

Bonnie shifted on the couch. She flicked dust off the armrest. She noticed a dirty plate on Cheyeanne’s bedside table and reached over to grab it.

“Like I wasn’t even human,” Cheyeanne said. “Like I was nothing.”

Bonnie stood up. “Can I get you something? Maybe some juice?”

Through the frustrations of Cheyanne’s recovery, we come to learn how she’s supposed to be cipher for American resilience in the face of catastrophe – whether or not she wants to be, whether she's actually resilient or just making do. It’s an uncomfortably personal take on what we – especially those of us who live outside the US – so often think of as a failure of politics.

Regardless of your credentials, being a freelance journalist is a pretty damn rough gig these days. Unless you have a wealthy benefactor or spouse - and can approach it more like a hobby, freelance journalism demands its practitioners to live on little more than a minimum wage income, and still attempt to summon the energy and enthusiasm to write kick-ass stories.

It’s a pendulum-like lifestyle, swinging from published byline to published byline with great periods of melancholy, and industry spite, between. I was between the vines when I read this earlier this year, and it re-affirmed, to me, the importance of pulling finger, and being a great journalist.

While I disagree there’s never been a more exciting time to be a journo, Pilon - a former New York Times reporter - reminded me there are opportunities there for those prepared to roll the dice – and keep them hot. As Carl Jung wrote, and Pilon quotes, “the reason for evil in the world is that people are not able to tell their stories.” Even though they won’t help pay the rent directly, they are words to hold on to.

I'm sure I am one of many who is immediately captivated by a story whose title begins with "The Strange Case". It makes me easy prey for empty clickbait articles. However, when the New York Times posted a story on someone called Anna Stubblefield -- a nearing middle-aged, married ethics professor who fell in love with a thirty year old man with cerebral palsy -- I was transfixed. Like most great writers who tackle an under-researched and morally ambiguous subject, Daniel Engber has crafted an open-ended piece. "The Strange Case of Anna Stubblefield" is deeply researched and disturbing. The questions it raises linger, unsolved.

I'm always interested in how far you can push a form until it's not that form any more. I'm at my most excited in the boundary just before breaking point where I feel like things become clearer in the disintegration of what we think we know about them. Conversation by Creek Waddington & Siân Torrington skates way out where the ice is the thinnest. It pushes essay, interview, conversation, lyricism, even the figure of the author themselves so far and to such great effect that it continues to leave me at once reeling and completely lucid. It teaches through body and emotional sensations as well as those of the mind. The whole Love Feminisms issue of Enjoy's Occasional Journal edited by Ann Shelton and Alice Tappenden is great (Rachel O'Neil's A Guide is wonderful) but the stand out for me was this incredible work which has to be read with the loosest of mental grips and the whole body.

Can any subject flood a story with more human interest than long-lost twins? ‘The Mixed-Up Brothers of Bogotá’ seemed almost to have strayed from the realms of magical realism (perhaps it’s the Colombian setting), stumbling into The New York Times Magazine to tell the story of a hospital switch that resulted in two pairs of identical twins being raised as two pairs of fraternal twins – one pair in a rural town, the other in the city.

The fascination of twins is the bait, but Susan Dominus’s deceptively straightforward telling does much more, luring us to a portrait of the complex,tender, and occasionally jealous relationships the four brothers formed after meeting. This could’ve been flattened out into a case study of nature vs. nurture, but Dominus allows the events to unfold with messy questions of guilt, longing, and fate still attached. Here, what is really the most specific of stories becomes a mirror for all our family entanglements, as well as celebrating the manifold and unknown ways we are shaped – and shape ourselves – into individuals.

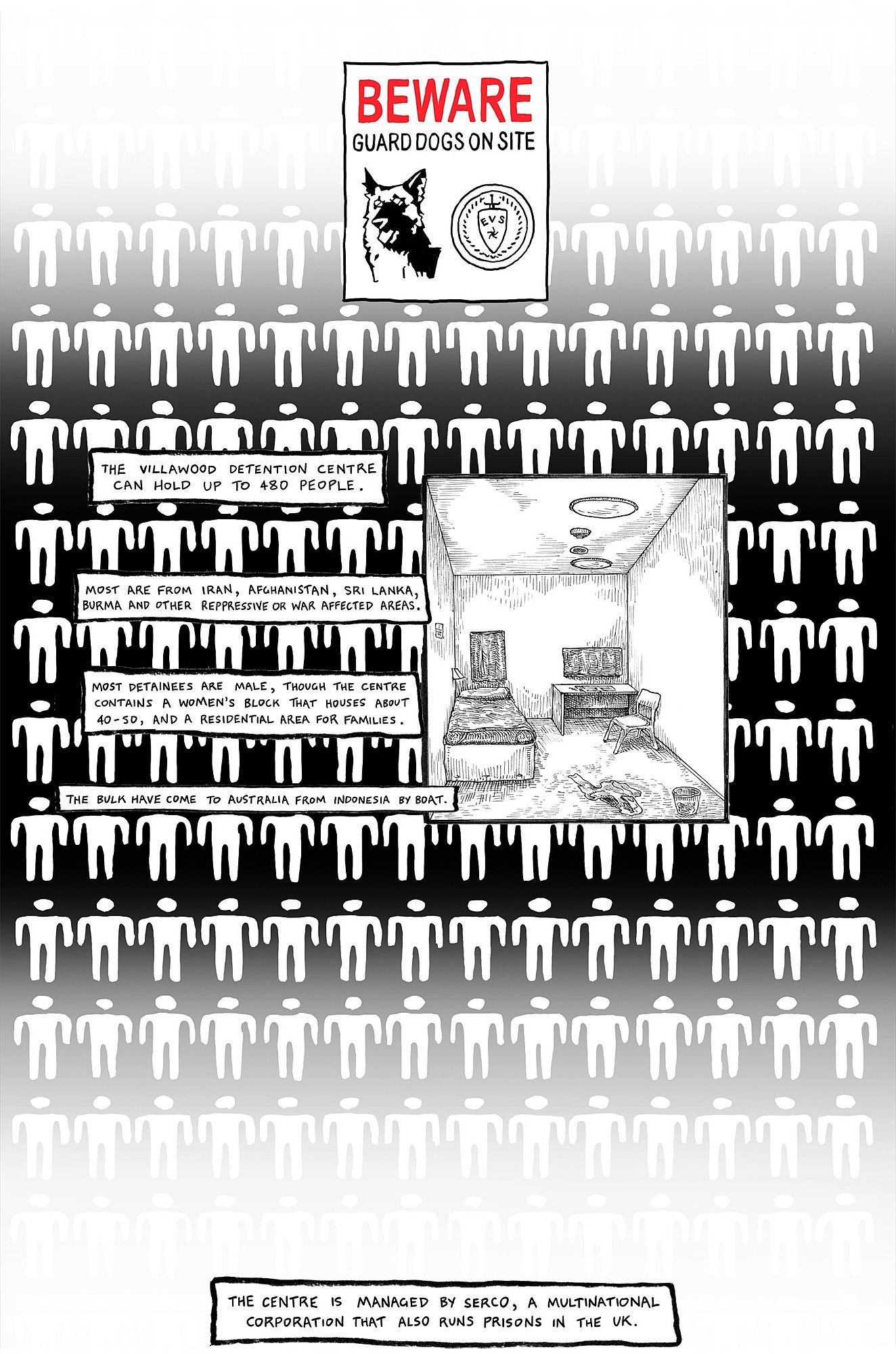

Long form non fiction graphic reporting and commentary is getting stronger every year and 2015 seemed a year when online publishers really embraced it. One which I encountered that stayed with me was 'The Shipping News' by Safdar Ahmed, a compelling piece written against and about the Australian practice of mandatory detention for asylum seekers. Villawood in Sydney is one of the few onshore detention centres that Australian activists can visit to provide support for asylum seekers and Ahmed’s comic communicates the ways in which the unending limbo of detention impacts on already traumatised people.

Much like Sam Wallman’s 2014 piece, 'At Work Inside Our Detention Centres', 'The Shipping News'shows us the strength of the graphic form at conveying emotional subtext:

“There are squirrels living in the spare bedroom upstairs. Three dogs also live in this house, but they were invited. I keep the door of the spare bedroom shut at all times, because of the squirrels and because that’s where the vanished husband’s belongings are stored. Two of the dogs—the smart little brown mutt and the Labrador—spend hours sitting patiently outside the door, waiting for it to be opened so they can dismantle the squirrels. The collie can no longer make it up the stairs, so she lies at the bottom and snores or stares in an interested manner at the furniture around her.”

I discovered the essay 'The Fourth State of Matter' by Jo Ann Beard, courtesy of a friend’s Facebook post just as 2015 eased into 2016, almost 20 years after it was written. It eloquently draws a picture of the author’s experience as her imperfect life and struggles are suddenly overshadowed by the shooting of all her colleagues. Its a story that feels depressingly pertinent for a 2015 marked by many mass shootings.

My visits to Jason Books, a second-hand bookshop on the characterful O’Connell Street in central Auckland, almost always result in the discovery of some remarkable piece of writing. This is due less to the quality of the store’s stock (though it does tend to be excellent) than to its owner, Maud Cahill, who is uncommonly well read, and so is an invaluable source of good things to read.

‘Pretty Violence’, a review by Tim Parks of David Shields’s War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Combat (New York: powerHouse Books, 2015), is just one of the gems Maud pointed me to last year. The piece bears the hallmarks of many of my favourite writings; it’s art-related, political in flavour, and barefacedly contrary.

Parks’s prose is a delight – easily elegant, without being (to adapt one of his pithy phrases) so concerned with an aesthetic that it becomes anaesthetic in its effects. The review gets bonus points for linking to an engrossing essay by Luc Sante on a cache of New York Police Department photographs that was unearthed a few years ago.

I’ll certainly be looking out for Sante this year, having also thoroughly enjoyed reading his decidedly not-from-2015 piece on William Boroughs, which I came to thanks to that genius of every year, Rebecca Solnit. She endorsed it in her deliciously sharp answer to Esquire’s ‘The 80 Best Books Every Man Should Read’, titled ‘80 Books No Woman Should Read’ – which, of course, no person should not read.

I subscribe to two magazines: The New Yorker and BusinessWeek. Every year they pile up and mostly don't read them until two weeks over summer, during which I scramble to get through what I can to pretend I'm a well-rounded citizen of the world. I don't read enough and I know it.

My favourite stories of 2015, then, are one from each of those magazines. There were no doubt better ones from all over, but I didn't read them.

'Where the Bodies are Buried', by Patrick Radden Keefe, looks into a decades-old murder, from the heights of Northern Ireland's very inaccurately-named 'Troubles'. I grew up in London in the '80s, and have the fuzzy childish memories of the bombs and bomb scares. That struggle was real. Given the masthead, it's obviously superbly reported, but I think the element which I found most profound and affecting was the vision of the ends-justify-any-means inhumanity of the IRA. Dragging a woman away from her screaming children to be executed on a hunch that she might be collaborating was considered all in the game – a mentality common to governments and militant opposition groups alike in that era.

The long coda, centring on Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams' life-long efforts to pretend the past never happened, is particularly queasy. It's like a twin to Lauren Collin's unbelievable story of English spy infiltration of the animal rights movement in the UK, which produced a fake marriage and a real child.

The Businessweek story I've chosen could really be one of a dozen: they're all essentially the same: six pages, maybe 2500 words, urgent, fun, brilliantly-designed. That is, apart from 'Code', the 38,000 word monster essay which was probably the most heroic thing which happened in publishing last year. Anyway – I picked 'The Ageing of Abercrombie & Fitch', about the rebirth and slow death of a retail icon. It has all these beautiful elements – a kind of genius in rapid decline, a once-sharp strategy now hopelessly dated and the machinations of boards and shareholders and management skirmishing in the background. It's a good time. See also, on the same theme, a story on another gross clothing guru, American Apparel's Dov Charney from 2014.

One last recommendation: Greg Bruce's pitch-black comedic World Cup odyssey for the New Zealand Herald.

If you’re jonesing for a read through-your-fingernails unbearable read about awful people, but wouldn’t mind mulling a few serious and valuable points along the way, Vox deputy editor Emmett Rensin’s piece on meeting MRA’s IRL had you covered. He emerges from his multiple nights out fraternizing with “Max”, a keyboard warrior from Chicago’s suburban flush side, refreshingly unsentimental.

Rensin’s snapshot of how his comfortable middle-class subject got to where he was vindicates my spitballing Overland argument last year that the internet is no place to raise your young men, more than ever, and we don’t have a social studies curriculum in most schools to counter its garbage island mythbuilding. Meanwhile, his obiter points (though they're not the most fluid parts, in my opinion) clarify some thinking I’ve been having for a while about the limits of rhetorical shorthand:

“The cudgel of "I am oppressed and this is my experience and you cannot speak to it because you do not know" is valid…but it is a seductive cudgel, too, especially alluring when it can be claimed without any of the lived experience that makes marginalization a lonely-making sort of suffering. American Christians are "persecuted" now; men are the ones being "squelched" by feminism; white Americans are the victims of "reverse racism."

Twisting, appropriating and turning established words and phrases for your own agenda doesn’t take a genius, though it helps if you’ve got a giant chip on your shoulder. Expect to see more of this stuff creep into the political discourse – it’s thrilled Trump’s seemingly put-upon followers to become a marginalised and re-empowered community, and I felt like it augured something in NZ politics when Immigration Minister Michael Woodhouse accused Green MP Denise Roche of being “paternalistic and colonialist” last year over her concern for climate change refugees.

As writer Morgan Godfrey astutely noted, Woodhouse was spouting drivel, a dead cat on the table to distract from a real issue – but the words still carry a weight well-reasoned activists have inculcated them with. Everyone fighting the good fight, then, is going to need to be vigilant on what they fall back on. If it’s buzzwords and not systemic persuasion, they’re going to find themselves in semantic battle with a mirror full of assholes, bouncing it all back in 2016 and beyond. Similarly, go back and take a look at Joan Fleming's blurb above - convenient ways of marking oneself as an ally are comfortable but ultimately self-limiting. I haven't bothered to read anything about Twitter increasing its character limit, but it sounds like a step in the right direction to allow for this.

I want to second "The Lonely Death of George Bell" too. It's a quotidian subject (or at least, as ordinary as death can be) given immense grace and gravity at N.R Kleinfield's hand. Sign of a really good piece is when you stop in your tracks and begin to apply its lessons to your own life. Increasingly, I've retreated into myself in the last couple of years or worse, allowed those around me to in a sort of tender neglect - this builds my resolve not to.