Loose Canons: Shilo Kino

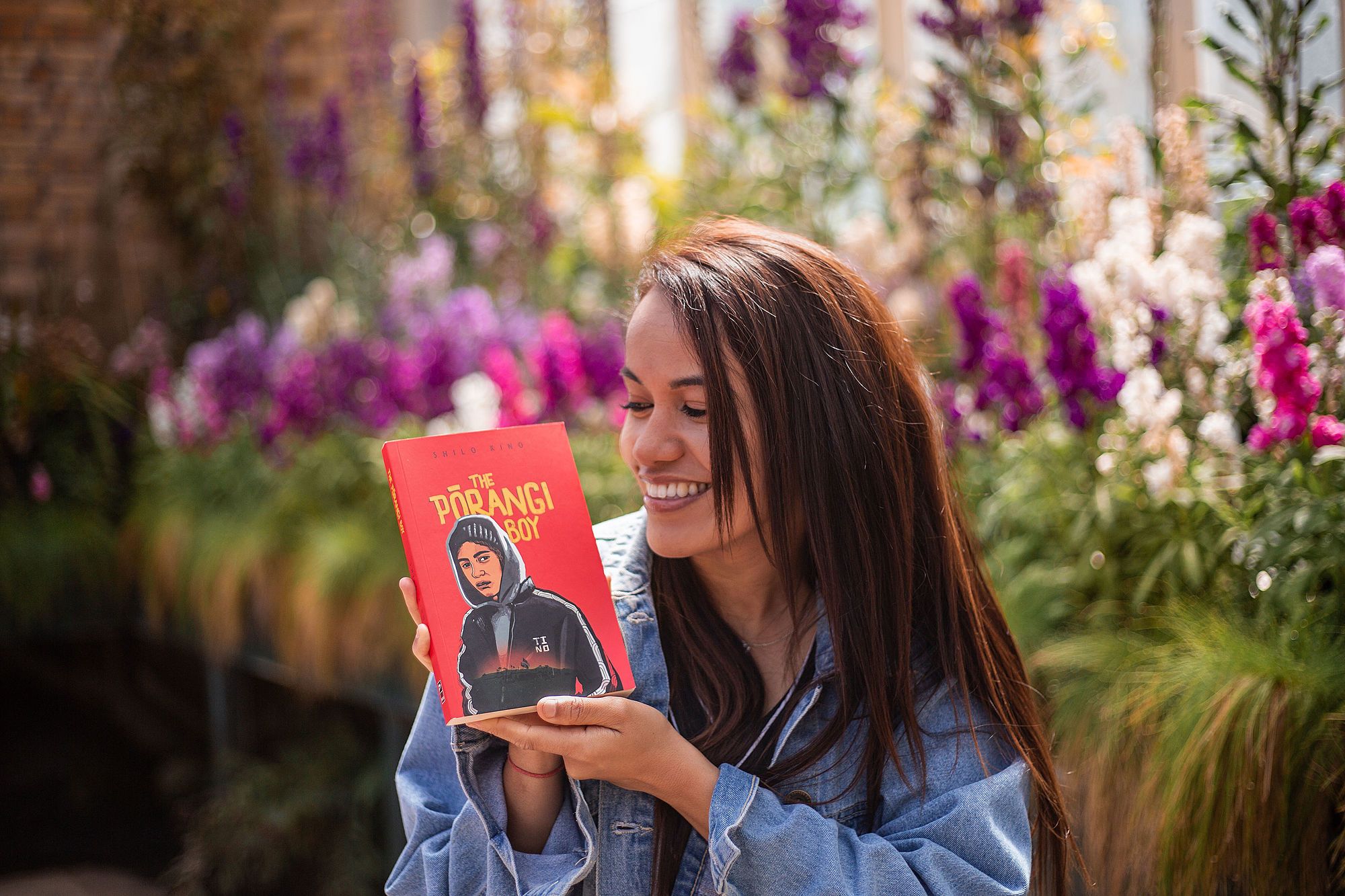

Shilo Kino, a writer and a TV journalist on Marae, tells us about the five Indigenous wāhine who influenced her life and inspired The Pōrangi Boy, her debut novel.

Loose Canons is a series in which we invite artists we love to share five things that have informed their work. Meet the rest of our Loose Canons here.

Shilo Kino (Ngāpuhi, Tainui), is a writer and journalist who has recently released her debut novel The Pōrangi Boy.

Image credit: York College ISLGP, Flickr

MAYA ANGELOU

Being aware of her displacement is the rust on the razor that threatens the throat.

The yearning to belong in a Pākehā world is like standing next to a well of water, taking sips but never quite able to quench the thirst. I stumbled across Maya Angelou like so many girls of colour around the world, unsure of myself and my frizzy hair and flat nose in a world where the M word (Māori) was always spoken with sharp daggers. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings spoke to my soul, it sang the melody that was aching in my heart. Maya told me I was never supposed to belong. She was my introduction to words that would commence my journey of writing.

Miriama Kamo

MIRIAMA KAMO AND MIHINGARANGI FORBES

My Māori identity was very much shaped by what I saw on the news. Child abusers, gang members, angry protesters, the same old narrative told through the lens of the coloniser. Seeing strong wāhine Māori journalists like Miriama Kamo and Mihingarangi Forbes on the screen stirred up feelings of pride, even if it was just for a moment. I never imagined I would go on to work in the same industry, or that those feelings of pride would ignite a burning fire in my soul and steer me to where I am today.

TOI MAIHI

Before Ihumātao there was Ngawha, and Toi Maihi. One of the lead protesters, Toi fought for years to stop the government building a prison on sacred geothermal land. Meeting Toi was a life-changing experience. I met her at a time when protests and activism weren’t mainstream and if you saw Māori activists on the news, they were ‘angry’ and ‘pōrangi’.

I sat with Toi and listened to her speak of the multiple protests and endless battles that resulted in the prison being built anyway. There was hurt in her eyes and trauma in her voice. She showed me a photo of a kaumātua who was arrested; I wondered what it would be like for a child to see their own koro arrested for peaceful protest – and so I started writing The Pōrangi Boy, centred around Niko, who has a close relationship with his koro. Protesting is not as glamorous as people think it is, it’s more than holding a picket sign. But the greatest lesson I learnt from Toi is we should all be activists. What she mourned for, what we all mourn for, is more than the loss of land. She mourns for the loss of sovereignty.

Image credit: Ngāi Tahu Pounamu

STACEY MORRISON

“You can be iwi hard and urban Māori proud.”

My decision to leave full-time mahi and learn my language next year in a full-immersion course is because of Stacey Morrison. If you ever get the opportunity to be in the same room as Scotty and Stacey Morrison, you are in the presence of spiritual giants. The room trembles and mana glows from their ahua, all without words being spoken. What’s special to me is that someone who grew up like me, who could only say ‘kia ora’, is now the greatest te reo advocate this country has seen. Stacey and Scotty built the waka, and we’re on it now, paddling in the same direction and often against some rocky waves. But at least we’re in it together, eh? One day I hope to be like Stacey, to be able to walk with my head held high in the world of Te Ao and to hold out my hand and bring others with me, just like Stacey does. Te reo Māori is my birthright and I might spend a lifetime getting it back, but what is of the greatest worth requires the greatest effort.

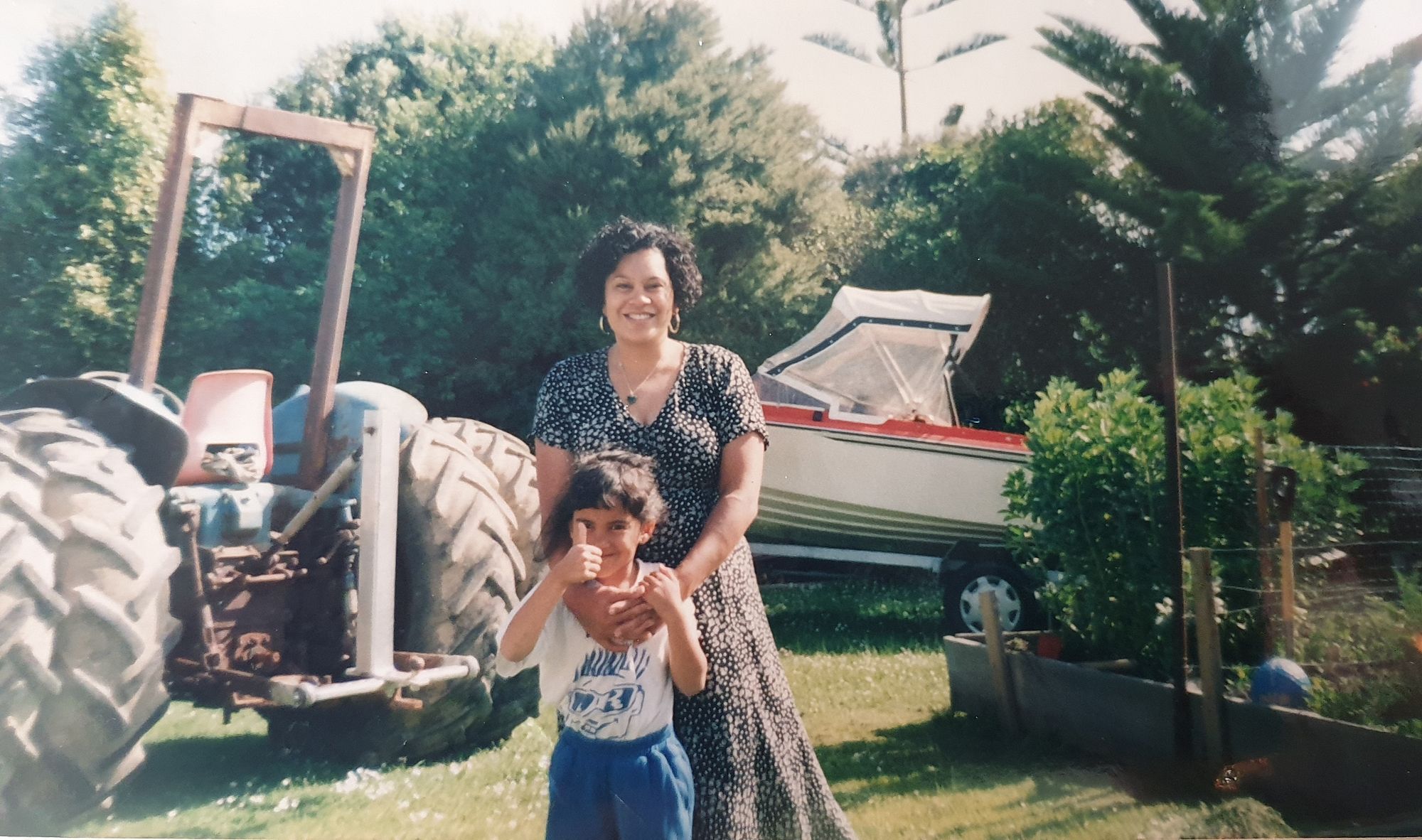

Shilo and her mother, Deborah Nolan

MY MOTHER, DEBORAH NOLAN

It is not until you become an adult that you begin seeing your parents as humans, and survivors of intergenerational trauma and colonisation. My mum was raising four kids at a time when there was no Brené Brown to tell her how to let go of shame. Therapy was something people did in secret and racists were still given an outlet to remind her she was inferior because of her whakapapa.

My mum turned her back on a world of gangs and fought her way into an unknown world where she became the first in our family to be educated, raising me in an environment where education was important and books were of great worth. There were times, as a child, when I would hear mum crying in the bathroom, and not know why; never truly understanding what she went through and sacrificed for us.

I know I’m a writer, not because my teachers told me so, not because I used to win prizes at school, and not even now because I’m an established journalist and published author. I know I am a writer because my mother told me so, at the age of five years old when I scribbled words on a paper and passed it to her, and she blu-tacked it to the wall and said, “My daughter, the writer.” All that I have, I owe to my mother.

.

The Pōrangi Boy is published by Huia