Ripening Together: Magical Fruit and a Precious Offering in 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart

Qianye and AL Lin remake cultural myths into personal narratives, reckoning with migranthood, Queerness and translation in a new, super-sized work, writes Gabi Lardies.

“Do you want a piece of skin to smell? Do you want to bite into it?”

Qianye Lin holds out a segment of grapefruit. She has just climbed back in through the window, having picked two yellow grapefruit from the tree outside. She sits on the daybed, bare feet scrunching a yellow blanket. Her younger sibling, Qianhe, known as AL, swivels towards her on an office chair. AL smooths the blanket, brushing off dirt carried in on Qianye’s feet.

We are in the siblings’ post-production suite, which doubles as AL’s bedroom. AL sits in front of an iMac on a long wooden table; Qianye’s MacBook sits closed beside it. A microphone is clamped to the table, next to a red ceramic baby – something in between a garden gnome and a Kewpie doll. Apart from the sheets gathered in a pile in the centre of AL’s bed, the room is neat; no clothes on the floor, no shelves filled with knick-knacks, no mugs on the table. Only a furry blue star-shaped cushion sits between Qianye and me on the daybed.

The starting point for 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart was the Ren Shen – a magical fruit “every single person in China knows”

The siblings are part of a group of young Queer migrant artists who flat together off Remuera’s prestigious Victoria Avenue. They are reckoning with their relationships to cultures, places, identities and practices. The path to their front door is paved in beige tiles, but long grass dries through the gaps. Neighbours have complained that the inattentive gardening is lessening the value of their properties, although none are for sale.

The occasional sound of a hammer banging comes from under the polished floorboards, where the group shares a workspace. Down there, the garage door is open and sunlight is streaming in. There is shit everywhere. A mannequin, floodlights, a mismatched collection of tables and desks, and the siblings’ filming studio: a plywood bay painted neon green. JingCheng Zhao (Jing) is constructing a wooden screen. Her paintings lean against the walls, and cables from tools spool across the floor. Two wooden tables hold Ningyi Hu’s and Angela Hu’s jewellery and ceramics. At the furthest end of the studio, Alex Su (Susu) works. His silver, frothy-yet-solid heart hangs from a hook on the wall, and giant, fuzzy pink petals lie beside a massive mirror.

A $400 light, Qianye Lin and JingCheng Zhao in the film studio/garage. Photo: AL Lin

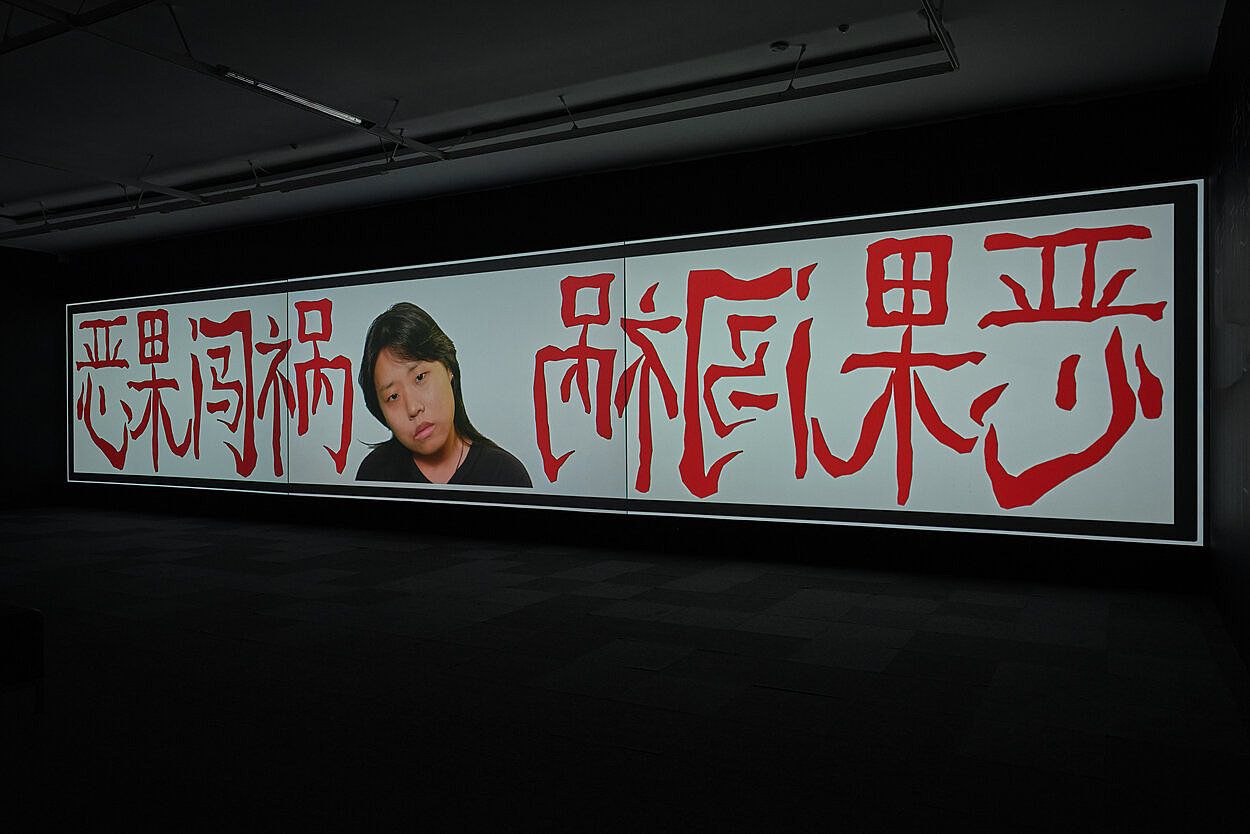

This is where the Lin siblings created 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, the three-channel, 7-minute video playing on loop at Te Tuhi until 8 May. The video marks an elevation in the siblings’ output – a work where all the visual and aural material is their own, rather than collaged from other sources. It is made up of footage shot on the greenscreen downstairs and digitally created imagery. Projected across an entire wall, over 14 metres wide and just under 4 metres tall, the work has a polished, high-definition texture. “It’s high production – like Imax,” says AL.

The starting point for 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart was the Ren Shen – a magical fruit “every single person in China knows”. Its story goes like this:

Legend has it that when the sky and the ground were not yet split, and the first chaos was just becoming discernible, a magical root formed … 3000 years to bloom, 3000 years to bear fruit, another 3000 years to ripen. The fruit is said to be shaped like a baby, if one is lucky enough to smell it, they will live to be 360 years old, eat one, then they will live for 47,000 years.1

Across China, shops sell baby-shaped fruit, which taste suspiciously like pears. “Of course they’re fake,” says Qianye, “but sometimes in culture there are things that live in between reality and fiction.” AL brings up photos of the fruit: they hang from tree branches, then sit wrapped in cellophane and a red ribbon. “People are suspicious, but more superstitious,” says AL.

Qianye Lin and Qianhe ‘AL’ Lin, What a thrill, WHAT A SUCCESS!!, 2020, Papatūnga, installation view. Photo: Misong Kim

Across China, shops sell baby-shaped fruit, which taste suspiciously like pears

Such mythology has propelled all the siblings’ collaborations. They are not the traditional stories but fable-like imaginings penned by AL and then expanded and edited by the duo. What a thrill, WHAT A SUCCESS!!, shown at Papatūnga in 2020, was driven by the story of Pig. Pig would learn human behaviours during the day, and then celebrate each night with human friends, finally returning to pig behaviour at midnight. It was a busy work: a giant peach and Mandarin text were painted on the walls, cartoon clips were collaged together and projected into the space, a large welded iron gate leant into the corner, and hearts, stars and arrows made of reflective tape decorated the floor. For one night only, an apocalyptic celebration took place at Papatūnga, with Qianye reading the script, people holding hands and skipping in a circle. Finally, a machine spat out bubbles.

After Pig came It, who came into the world as a formless being. In the three-channel video Thus the Blast Carried It, Into the World 它便随着爆破, 冲向了世界, an oracle narrator tells the story of It as it learns the laws of the world through immersion, re-experiencing the world in an endless loop without access to structures of meaning. This work was originally commissioned by The Physics Room in Ōtautahi and shown there in early 2021. Later that year, it was shown again at Coastal Signs, Tāmaki Makaurau, accompanied by a new “super-professional big-boy book” of the same name. Its 115 glossy pages gather the Pig and It scripts, in both Mandarin and English, pieces of writing by JingCheng Zhao and Sarah Hopkinson, and visual documentation from both shows.

Qianye Lin and Qianhe ‘AL’ Lin, Thus the Blast Carried It, Into the World 它便随着爆破, 冲向了世界, 2021, The Physics Room, installation view. Photo: Janneth Gil

The Lin siblings have been gaining recognition as a duo. Only three years ago I would pass them in the Elam School of Fine Arts hallways at The University of Auckland, rarely alone or with only each other – there was always also Jing, Susu, Ningyi and Angela. Back then, they shared studio space provided by the university, and the friends were all members of a programme within the art school called Studio International.

Studio International was set up for international students, students for whom English was a second language, and those who were migrants or children of migrants. It became a place to forge community and a sense of belonging in a place that may have otherwise been isolating. “Imagine you’re a Mandarin-speaking migrant in Auckland, and you’re an artist, and you’re also Queer,” Qianye says. For her the group is “a little bit like a family born of desire, but at the same time, necessity.”

“Imagine you’re a Mandarin-speaking migrant in Auckland, you’re an artist, and you’re also Queer”

In Qianye and AL’s years there, the programme was run by Yona Lee. Zooming from an artist residency in the Netherlands, Yona remembers the siblings and their friends as a “special group that bonded together.” In Susu’s words, “besties.” By 2019, this smaller group within Studio International had become core members – they came every week, participated, were vocal, and wanted to collaborate and help each other. They had gained momentum, having been involved in the programme for a few years. The group put together the annual Studio International exhibition at ProjectSpace differently from previous years. Rather than a show with members contributing individual works, they worked collaboratively to create A Mass of Pub-a-Pub-alee. This installation included a video inside a paddling pool, spray-painted text and drawings on the walls and floor.

An apocalyptic celebration took place, with Qianye reading the script, people holding hands and skipping in a circle

Qianye Lin and Qianhe ‘AL’ Lin, What a thrill, WHAT A SUCCESS!!, 2020, Papatūnga. Photo: Misong Kim

It is this group of besties who skipped in circles as part of the live performance for What a thrill, WHAT A SUCCESS!!. For Thus the Blast Carried It, Into the World 它便随着爆破, 冲向了世界, Ningyi did the costume, makeup and set design; Susu worked on the set and makeup, rendered the mountain background and the final scene, and Jing was the videographer. In 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, Jing was behind the scenes again. “You should have seen it – the greenscreen lit with a Bunnings light – the face lit with our expensive $400 light, and then Jing was holding a blow dryer for my hair,” says Qianye. “Susu rendered the green baby we used in the video,” adds AL.

Hallways weren’t the only places I ran into the group that year. In 2019, mana whenua at Ihumātao called for solidarity, and people joined the land occupation in their thousands. In the rain with mud soaking my hems, I watched Qianye and AL stand as part of the group Asians Supporting Tino Rangatiratanga, which was formed to show solidarity with Māori struggles for sovereignty, and to position Asian migrants as tangata tiriti. They carried a banner that read: ‘ASIANS STAND WITH IHUMĀTAO’. The inside of the O was cut out, and group members would occasionally peer their faces through as if it was a cut-out photo board.

Their relationship to Aotearoa is “complicated”. “We can't just use the landscape for our own ends"

The siblings are acutely aware of their tauiwi status on colonised land. They first followed their mother here in 2002 when she came to study, each staying temporarily for stretches of months before returning to Zhuhai, China. In 2013 AL moved indefinitely to Aotearoa when they were 15, and Qianye followed in 2014 when she was 18. Though this seems formative, it is relayed quickly and minimally, and wrapped up with, “But anyway – where were we?”

Their relationship to Aotearoa is “complicated”. “We can't just use the landscape for our own ends,” Qianye says. The European settler structures are obviously built to alienate migrants not of European descent, and then there is the actual land – of which so much has been taken from mana whenua. They are still unpacking their positioning here and unravelling what relationship to the land could be possible in a decolonial context – especially since, as AL puts it, “we came through the Crown, so our relationship to colonial violence is tangled.”

They have never filmed on location because they have never felt licensed to film the landscape in Aotearoa

They have never filmed on location because they have never felt licensed to film the landscape in Aotearoa. The landscapes in their videos are either collaged from Chinese cinema or digitally generated by AL. They draw on the siblings’ time growing up in the People’s Republic of China. Qianye turns to AL, “Can you google 和谐社会, please?”

A collection of bright, photoshopped outdoor scenes appears on the iMac. They are collaged from stock photos: lime-green grass, lurid blue sky, a miniature rainbow, a smiling Chinese family, tulips in the foreground. They are caricature-like – almost satirical in their falsity. The siblings laugh, but there is bitter disbelief in their voices. “Nobody believes it... but this is everywhere.” Qianye remembers the images being used by the Chinese government alongside slogans of harmony. She points, “Look at this! 'Love, Happy, Wish, Dream.’”

Like the Ren Shen fruit, the images are a myth – obviously fake, but so ubiquitous they become part of the landscape, and people forget how absurd they are. Having been in Aotearoa for the better part of a decade, the siblings can view these images from a distance.

Like the Ren Shen fruit, the images are a myth – obviously fake, but so ubiquitous they become part of the landscape

Qianye Lin and Qianhe ‘AL’ Lin, 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, 2022, three-channel video, 7 minutes 16 seconds, Te Tuhi, installation view. Photo: Sam Hartnett

They draw from their shared past, pulling cultural myths from early memories and reconstructing them into new personal narratives. In 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, it is Qianye and AL’s faces that stare back at us. At Te Tuhi, AL’s face is in the centre. They speak their poetry – the video slowed slightly – and large red Mandarin characters spread across the rest of the white field. In a following frame, rain falls onto a digitally generated artificial sea. Qianye’s face is superimposed on top, eyes directed at the viewer. Her hair blows back. They are without makeup, without costumes, tightly held in the frame. “From the start, I wanted both of us to appear in this work; I see this work as the closest to us as who we are, the two of us,” says AL.

It is difficult to write about the siblings as separate people. They seem like two fruit growing from the same tree, from the same tip of the same branch, ripening together. While we talk in the April sunlight, there is always a “we” and never an “I”. Sometimes, they confer privately between themselves before deciding on an answer, but usually, it seems as if everything has already been discussed over bubble tea. In AL’s bedroom, they spend long hours working side by side (until 11pm, when Qianye knows AL will start to think “everything is shit”). They also play long, complicated board games like Ticket to Ride: Europe, cook together, and spend time with their flatmates and collaborators. AL’s ironic “How beautiful, best friends” is quickly met with “No, but it’s true!”

In 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, it is Qianye and AL’s faces that stare back at us

A moment of rest during installation at Te Tuhi. Photo: AL Lin

While their practice happens between themselves, they consider their audience. In making 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, there has been a “hellish translation process – the worst one yet,” says Qianye. One translation in particular “made our hearts bleed.” The character 果 “means fruit but it doesn't only mean fruit.” Its use implies layered meanings, actions having consequences, efforts being met with results, there being expected outcomes to events, expectations, and the way things unfold. In the English subtitles, it appears simply as “fruit” – its associative, multiple meanings inaccessible.

AL wrote the series of texts that appears in the video in an ancient Chinese format – which is impossible to translate. They aren’t interested in creating perfectly legible work prescribed for an imagined white audience, or pandering to Anglo-centric views. They want to honour their own relationship to language, and share that with others. “This work is made for sharing,” says Qianye.

Qianye bites into a segment of grapefruit. It bursts, sending droplets flying

“Everything about this work is true to us,” says AL, bringing their hands towards their chest facing upwards and outwards, as if offering something sweet and delicate, “we give this, but in a precious way. You can have it, but we hold it.”

Qianye bites into a segment of grapefruit. It bursts, sending droplets flying. She uses the star cushion to mop up the droplets on my recorder and the yellow blanket.

1 This is a condensed excerpt from Journey to the West, a novel written by Wu Cheng’en and published in the 16th century, during the Ming Dynasty.

Feature image: Qianye Lin and Qianhe ‘AL’ Lin, 人参果之歌 A Very True Heart, 2022, three-channel video, 7 minutes 16 seconds, in Ata Koia!, Te Tuhi. Photo: Sam Hartnett

*

Gabi Lardies is a cadet in the Next Page cadetship programme, public interest journalism funded through NZ On Air.