15-Year Journey: A Review of Yātrā

Eight theatre pieces speak to different issues, politics, themes – but all pertain to one’s ‘journey’. Rina Patel reviews Prayas Theatre Company’s latest show and reflects on its community and history.

A political medley of sorts, Yātrā is also a milestone. A Sanskrit word that roughly translates to journey, ‘yātrā’ is a fitting name for a show that reflects Prayas Theatre Company’s 15-year journey of evolution and refinement.

Established in 2005 and now deemed the largest ensemble South Asian/Indian theatre company in Aotearoa, Prayas is based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. The rōpū is strong in number, with members representing the many and varied states from within the Indian subcontinent and diasporic whakapapa.

The heart of Prayas is community. ‘Prayas’ – in short, meaning ‘attempt’– lives up to its company name in what it offers its members. Artistic Director and co-founder Amit Ohdedar has, over the years, built a beautifully welcoming, all-inclusive company ethos that has successfully fostered talent from within, where members are given opportunities to perform, produce, direct, write and more, always guided by those that have gone before – and in 15 years, many have trodden those very foundational floorboards.

What we see on stage is only the tip of the iceberg

What we see on stage is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what each company member has learned and experienced within the rehearsal-room walls. This process of developing talent is a key part of the Prayas kaupapa, creating space for longevity and a sustainable future of confident practitioners. Its co-founders knew what they wanted from the outset and have pursued it through a plethora of classical and modern Indian plays.

There is a confession I must make here. Whereas the members of Prayas predominantly come from immigrant backgrounds, I am a child of an immigrant (Dad) and a first-generation New Zealand Gujarati (Mum). So my viewpoint will have a strong Kiwi-ised Indian lens, which is very much a different voice; even though I may look full South Asian/Gujarāti, my accent sure reflects a New Zilund one. Just saying.

The second confession and parallel I must make is in respect to my historical background as a former member of The Untouchables Collective. In Pōneke in 2004, after my three-year training as an actor at the reputable Toi Whakaari, our pioneering South Asian ensemble presented a play called Yātra: Journey for Identity, devised and directed by Jade Eriksen, which boldly explored our South Asian/Indian identities in Aotearoa via movement, sound and metaphor, some of which evoked memories and sensations of India.

Yātra flyer, 2004

Our title only had one macron, at a time when macrons were hardly used. Our 2004 production had both trained and non-professional South Asian/Indian actors, several of whom shared a New Zealand-born heritage, including myself, and Tarun Mohanbhai and Raj Varma (Those Indian Guys).

The Untouchables Collective was short-lived, simply because we were a bunch of like-minded practitioners who wanted to come together, create and share work but we weren’t necessarily interested in formalising the group into a registered company. We didn’t have a canon of New Zealand-Indian plays to draw from then – and still don’t, really. This is yet to come, I’m sure. Lisa Warrington wrote about this lineage in “Brave ‘New World’: Asian Voices in the Theatre of Aotearoa” (Australasian Drama Studies, No. 46, 2005).

15 years ago there were only a handful of us ... jump-cut to now and there are enough South Asian practitioners to fill Basement’s Studio theatre space

But it’s in the here and now that fellow Toi grad and most recently Arts Foundation Laureate Award-winning theatre practitioner Ahi Karunaharan has cleverly produced and named this production Yātrā (with two macrons); perhaps to echo the lineage of Indian theatre makers who came before, and to showcase Prayas Theatre Company and reflect how far they have come. Eight carefully curated separate theatre pieces speak to different issues, politics, themes – but all pertain to one’s ‘journey’.

I must also point out, 15 years ago there were only a handful of us who were trained South Asian theatre practitioners, none of whom were reviewers; jump-cut to now and there are enough South Asian practitioners to fill Basement’s Studio theatre space. Yet, not all of us that are on the ground are privileged enough to review. So here we go.

•

A spotlit woman (Aarti Kansara) opens the show as we find ourselves an audience at an English-speaking forum, where she confesses English is not her native language, but has now become the language of her thoughts, reasons and the language she uses for loving.

We segue into the first short play, directed by Amit Ohdedar. Keats was a Tuber is a satirical story set in the 1970s, in the English department of an Indian university, where an older staff member, Mrs Nathan (Nona Shedde), announces the sudden appointment of a new staff member, her nephew, played smoothly by Ruzbeh Palsetia. Dressed impeccably in 70s garb with a hint of Anil Kapoor, he arrives unexpectedly to ruffle the feathers of the rest of the staff, who don’t realise just how entrenched they have become in an old institution.

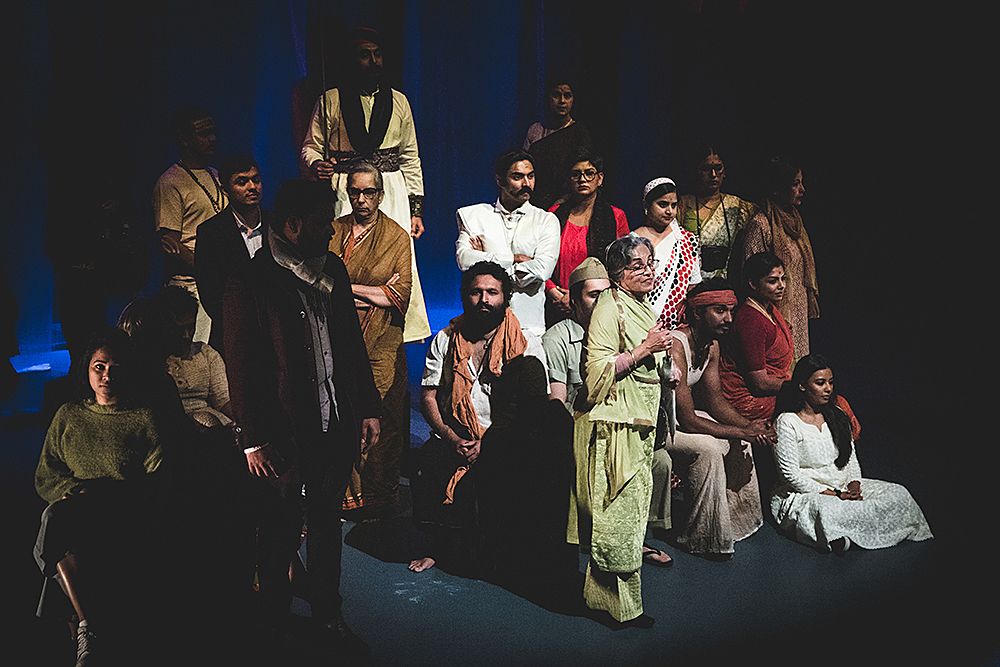

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

Next, I Really Have to Meet Godbrings together the lives of two household servants (played by co-founder Sudeepta Vyas and Shivneel Singh) in 1980s India, who try to outwit each other. Directed by Rishabh Kapoor, it has the scope to really go further stylistically with their absurdist behaviour, and for now has only just warmed up.

Smashing down the metaphorical wall of patriarchy is Aurat,written by an informed political figure who was indeed male, Safdar Hashmi. Sneha Shetty, who has performed in various Prayas productions, makes her debut as overall Assistant Director for Yātrā. In Aurat, Shetty’s direction reveals a great on-stage ensemble energy filling the space with a sense of play and warm hubbub chatter. We are immersed in a house party where the men fast become peripheral and the women, by the end, form a powerful dynamic that somehow cuts through the air.

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

Former Prayas actor Aman Bajaj takes the helm as first-time director for two pieces, the first of which is Know the Truth,set in what looks like a talk-show-style set. Shweta Tomar plays the host. We get a glimpse into primetime TV manipulation and the distortion of what is really happening politically, as bombings are brushed off as fireworks, ambushes as common disturbances, and so on. Families are being torn apart, yet this newsroom host cunningly covers all that bad news with sugar-coated answers to appease and deflect the truth. At times there was a repetitiveness and perhaps having a co-host on stage to balance out the conversation would have improved the interplay between actor and audience.

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

Candid and intimate, Guards at the Tajexplores a day in the life oftwo imperial guards who are on duty as the Taj Mahal is being built; they are forbidden from looking at it, threatened with being fired and outposted. The 1600s Mughal costume design (Padma Akula) is divine. Raj Singh plays Humayun, the older, stoic guard, who manages the juvenile, lust-hungry Babur, a celestial, dreaming optimist, played by Agustya Chandra. They reminisce together, only to find themselves questioning their vocation as dutiful guards.

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

A company member since 2005, Sananda Chaterjee has turned her sights here towards associate producing Yātrā as well as directing Ten Ton Tongue, a powerful monologue that rides the wave of the Me Too movement and is clearly the most experimental piece in the set of eight plays. Three women, played by Porvi Fomra, Gemishka Chetty and Aarti Kansara, start off separately in a triptych-like set-up, each masked behind a clear yet blurry screen, giving a cold, sterile feel, as abstract music begins to pulsate. Via a poetic and loaded feminist text, they make their way towards centre-stage, now clearly visible, eventually entwined with each other as one voice in a simple yet effective choreography. An ambient, contemporary Western soundtrack underpins the poetic lyricism of the way three voices in the end are really one, and that consent is vital. The physical embodiment of hate and rage reaches a tipping point with Gemishka Chetty blowing her fuse at the audience. She is one, yet we know she speaks for all women.

The piece with the largest cast, one of two directed by Rishabh Kapoor, is Thaneer Thaneer / Water Water,which looks cleverly at water scarcity in a remote village, and the widespread political corruption in rural Tamil Nadu in the 1970s. We learn that in order to be heard by the authorities you don’t always need to resort to violence and rioting; sometimes you can be heard by strategically boycotting an election or, in this case, harbouring a convict (really a failed hero, born into bonded labour) to get the attention of an influential journalist. Thaneer Thaneer echoes elements of Ahi Karunaharan’s socio-political epic Tea (2018) – the complexity of politics, human justice and archetypes are all present. This ensemble piece is beautifully cast and has a true classical staging style, always facing out to the audience. The vocal work in this piece is clear, allowing the story to be conveyed with clarity and focus. Kudos to each actor in this piece, all adorned in great costume detail representing a wide scale of caste and class. Naiker, played by Utsav Patel, naturally relishes a high-status role. It’s a shame the black nylon umbrella isn’t of the right era.

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

Bringing us towards an ensemble ending, we are transported to Harlesden High Street, a poetic piece about the immigrant experience in the UK, directed by Prayas co-founder Amit Ohdedar. Rehaan (Ansh Malhotra), a first-generation Pakistani immigrant, runs his stall in tandem with Karim (Bala Shingade) at the behest of his deceased father, who Rehaan believes lives within him as a ghost. Rehaan sells bespoke world maps in which Pakistan is intentionally large and centred – a quip about wanting to be noticed and acknowledged by the West.

Ayesha Heble (Ammi) gives a strong, convincing performance as a loving mother to her son Karim. At times her fellow-Indian-immigrant-deprecating humour is gold. Karim wears a very English-looking scarf, symbolising the English–Indian experience of adaptation and survival. The only time business booms is when it rains, as a makeshift roof brings members of the public together to share shelter – but only ever for a moment. Backdrop projections of forest blanketed in snow play as Ammi and Karim reminisce, on a bus ride home. There is a sadness and a sense of dislocation – a theme most Indians of the diaspora can relate to. The Prayas ensemble adds a warm, blanket support to these three characters who rub up against their respective identity crises. We come to a collective ensemble end.

Yātrā. Photo credit: Ankita Singh Photography

Prayas has curated a rich programme that hangs off eight strong, mostly classically written plays. Again, the concept of the journey resonates with each director in this show, all of whom cut their teeth as actors with the company. The clever curation caters to each director with care and awareness of who they are as an individual and allows them to extend their personal strengths. Bajaj possesses the humour and comedic timing, Ohdedar the classical English lit-wit, Kapoor a progressive twist and vision, and Chatterjee gets to indulge her neo-feminist tastes while Shetty explores women’s rights as a woman in her own right. A big shout out to the marketing and publicity team (Alisha Iyer, et al) for all the wonderful online curation of show profiles and video bites.

New talent is strategically and seamlessly embedded into the large ensemble cast. No stone has gone unturned here. All players have naturally slotted into roles that are neither out of their depth nor too comfortable. There is a tender balance of skill and talent development carefully at play here.

Producer Ahi Karunaharan’s depth of professional industry experience has, over the years, assisted Prayas in shifting and developing its foundational aspects, and this is a gift that I’m sure will keep on giving as long as the kaupapa and vision of Prayas remains strong. The framework of Prayas is solid and a testament to its 15 years of steady, strategic growth, held up by the pillars of committed and wise co-founders. May it continue to shift and evolve for many more.