Review: Voices of the Land: Nga Reo o te Whenua and Sol LeWitt

Profiles of the American artist Sol LeWitt and the New Zealand ethnomusicologist Richard Nunns explore the passage of cultural knowledge - and all its disruptions, too.

One of the great pleasures of seeing films in a festival context is the discovery of unexpected thematic and textual links between ostensibly disparate cultures. For perhaps obvious reasons, this phenomenon seems to occur more frequently in the documentary realm than with fictional worlds. Case in point: profiles of the American artist Sol LeWitt and the New Zealand ethnomusicologist Richard Nunns share an avid exploration of the passage of knowledge, and disruptions to it, both through time and down generations.

The sounds produced by taonga pūoro—traditional Māori instruments—have become commonplace in this country, to the point where, in certain settings, their absence is noticeable. Radio New Zealand recently introduced new theme music for some of its shows, among them Morning Report; the appearance of certain taonga pūoro in the cue before the 8am news bulletin now reveals both the absurd blandness of the synth-driven ’80s track it replaced, and just how central these instruments and their sounds have become to our sense of national identity at the start of the 21st century. Te Reo Irirangi o Aotearoa now truly “sounds like us.”

Director Paul Wolframm (Stori Tumbuna: Ancestors’ Tales, NZIFF ’11) has crafted a rigorous, in-depth profile of Nunns, who is the preëminent scholar of taonga pūoro. As its title would suggest, Voices of the Land: Ngā Reo o te Whenua explores, through Nunns’ life and work, the notion that traditional Māori instruments, music, and waiata are inexorably linked with the physical features (the geography and geology) of the land in which they were created. In doing so, Ngā Reo o te Whenua functions, in part, as a celebration of the quickening renaissance enjoyed by te reo, and by Māori culture more generally. (As such, to this writer’s mind at least, the film barely needs its English foretitle.) Most interesting is the film’s intellectual endeavour to educate viewers about the differences between Western musical traditions and instrumentation and those of the Māori. Many taonga pūoro went unheard for most of the 20th century; Nunns is credited, as Bill Gosden notes in the festival’s programme, with “retrieving [them] from the silence of the museum,” sometimes single-handedly.

The film is deliberately paced to match both the slow rhythms of Nunns’ multi-faceted story, and his now-limited physical abilities: an auxiliary concern was to document Nunns’ affliction, in recent years, with Parkinson’s disease. Wolffram reveals information piecemeal, and in certain cases even occludes it until it is absolutely necessary to understand what has been happening on screen. Nunns is an erudite speaker, and appears a remarkably patient man; even to the uninitiated viewer his absolute expertise in his field is evident within the first few minutes of his appearance. The only downside of the film’s construction is that, to those unfamiliar with him, Nunns’ speeches perhaps seem more like pronouncements from on high than the miniature academic essays they evidently are.

Ngā Reo o te Whenua is a deeply spiritual journey; the film’s undeniable beauty is predicated in the marriage between Alun Bolinger’s plentiful cinematography and Tim Prebble’s faultless, emotive sound design. For the bulk of the documentary’s 100 minutes, Nunns traverses Te Waiponamu, the South Island, playing instruments with Horomona Horo, who is something of an apprentice of his—though, as with other facts, this isn’t made explicit until late in the piece. Performances in honour of Nunns given at a concert at Te Papa some years ago are threaded through the film. Wolffram looks at Nunns’ work largely through his collaborations: principally with the late Hirini Melbourne, but also with the master carver Brian Flintof, and a host of musicians and other artists, many of whose works pay tribute to Nunns and the intellectual opportunities he has created through reviving these art forms.

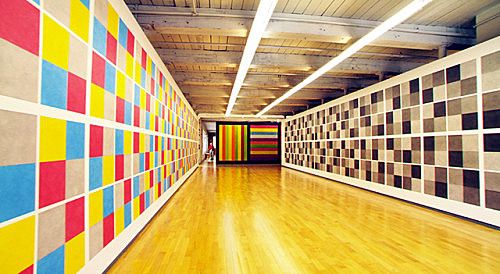

Chris Terrink’s comparatively homogenised Sol LeWitt, is, by contrast, a portrait of the artist as an absent presence, so to speak. It is distinctly not biographical. LeWitt, who died in 2007, was camera-shy and avoided fame, stringently opposing any notion of the artist as a personality. Core to his understanding of conceptual art (judging by Terrink’s slender and slightly hollow film) was the elimination of the artist, or any notion of her influence, from the work. Permanence was not a concern of LeWitt’s; many of his works were ideas to be realised, and nothing more—he would have been happy, as one commentator says, to have some of them exist for only an hour. He never attended an opening, and rarely posed for photographs.

Maintaining this philosophy, Terrink’s film includes LeWitt only as an abstracted voice in a filmed interview, and then only very briefly. The documentary concerns itself with surveying, in especially eloquent visuals, current expositions of his pieces on gallery walls, and with the realisation of one LeWitt’s “Wall Drawing #801” by a group of assistants. The finished work, installed in 2011 in the interior of an art-museum tower in Maastricht, Holland, is a minimalist piece, grand in scale, that makes a feature of natural light: concentric circles, spaced at exacting, mathematically evaluated distances, are painted onto the conical wall. This involves applying floor-to-ceiling runs of masking tape on the surfaces before inky blackness takes over the interim spaces. Many people, and much scaffolding, is required for this purpose. The film exits these preparations every so often to examine LeWitt’s work posthumously through interviews with friends and colleagues, referring to archival material only rarely. His Italian period, which reveals the origins of his “Wall Drawings” concept, seems to have been his most life-affirming, and is presented here with the most warmth and appreciation.

The connection with Wolffram’s film is in the way that the artist and the academic-musician are repositories from whom information and ways of working are learned and applied later—even, as with LeWitt, absent the creator. As these two films show, the gallery assistants in Holland are not dissimilar to Nunns’ scholarly colleagues and apprentices; what is important is that ideas and interpretations are retained for future generations—along with instructions on how to best use them.

Voices of the Land: Ngā Reo o te Whenua, a film by Paul Wolffram

New Zealand · 2014 · 100 mins.

Sol LeWitt, a film by Chris Terrink

The Netherlands · 2014 · 72 mins.