Longing for a World Yet to Come: Nostalgia in Contemporary Politics

Andrew Dean considers his family's heritage as Jewish refugees, his formidable great-aunt Frances, and the important and often misused relationship between nostalgia and politics.

Andrew Dean considers his family's heritage as Jewish refugees, his formidable great-aunt Frances, and the important and often misused relationship between nostalgia and politics.

One weekend afternoon, at the end of the last northern summer, I was in my back garden, working on my thesis, drinking a cup of tea, and eating a biscuit. On this afternoon I was listening to Bach – the Brandenburg concertos, to be precise – in the shade of the apple tree. As the trumpets came in, I felt myself transported. I’ve been here before.

And suddenly the memory appeared. The sound was one that I’d heard in my great-aunt Frances’s sitting room in her flat in Sydney, underneath the conversation, chugging away, straining to make itself heard, at least two decades ago. There I was, eight or ten years old, sitting across the coffee table from this formidable woman, next to her stereo, which was set to a low jangle. She offered me sparkling water – sparkling water, something I didn’t know you could do to water – to go with her triangle-cut cucumber sandwiches. Hearing Bach that afternoon under the apple tree, her room formed itself in my mind, without any effort on my part. The art all over her walls – over her shoulder was a brushy three-foot-high nude, another shock – and the cucumber slices and cream cheese. There I was, listening to this woman who could only ever speak in full sentences, descending cadences; my aunt, sure, but utterly foreign.

Frances died recently. It was a long and difficult decline: dementia... a rest home. An unpleasant way to go for a woman of singular style and refinement. She never became less foreign to me over the years, never less mysterious...

Frances died recently. It was a long and difficult decline: dementia; some legal difficulties; a rest home. An unpleasant way to go for a woman of singular style and refinement. She never became less foreign to me over the years, never less mysterious – in fact, neither to me nor much of the rest of my family. Here is what I know. She was born in London in 1928, the daughter of two Jewish refugees, Harry and Jenny, who worked in the rag trade. Jenny was from Latvia, Harry from Poland. I say refugees, and I say Poland: it was Russia then, and it would become Russia again, before again becoming Poland; and they were both escaping war and the pogroms.

According to Frances – although I’m already getting this second hand – Harry left at the outbreak of World War One to escape conscription, which for Jews in the Russian army meant almost certain death. He spent a year travelling across Europe with nothing but the clothes on his back, before arriving in Britain, where he was conscripted, successfully this time. He didn’t have a surname, and took what he was given, ‘Wislaw.’ It was the anglicized version of the town he had left, and a name that for the rest of his life he could not pronounce.

Frances was brought up in the East End. She was evacuated to the countryside during the Blitz, and hated it – she couldn’t stand the provincial life. She emigrated along with my father, grandparents and great-grandparents to New Zealand in the early 1950s, and hated it almost as much. It turned out that she didn’t like Britain’s farm much more than she liked British farms; she soon left for Sydney. She spent some time in Israel, although how long, or why, I’m not sure. She spoke French and Italian; she cooked mighty meals; she drank fine wine; she made cucumber sandwiches. Last time I saw her, at a family wedding, she told me that if I wanted to do a degree in literature I should read Proust – and learn the French to go with it.

A departed world comes rushing back, not as symbol, but as reality, the presence of another world within this one.

The experience I had that summer afternoon is one we all know: that of walking in a past time that emerges, all at once, out of the least likely of materials. A certain smell, sound, or feeling – stretching out your legs in a cool bed on a summer afternoon, perhaps, or listening to Bach under an apple tree. A departed world comes rushing back, not as symbol, but as reality, the presence of another world within this one.

My great-grandfather Harry knew what it meant to inhabit the irrevocable past. Living out his life in suburban Christchurch, he was stuck giving a name that wasn’t his, in a language he never mastered, for a place to which he could never return. Poland was behind the Iron Curtain, and anyway, there was no shtetl to return to, neither for him nor for the Jews of Eastern Europe: a whole way of life departed. So there were Harry and Jenny, and perhaps Frances too: remainders of 20th Century history, the survivors of a political order that had cast families, places, names, histories, and time itself, to the breeze.*

I have begun with this material for a number of reasons, but one of them is that I want to appeal to a register quite different from how we normally think about politics – I want to appeal to feeling, specifically feelings that we have for the past in the present. We have seen this condition of living – that we all live with ghosts of the past – become motivated politically over the last year or so. I told a story, one that translates quite quickly into politics, I think, not through making propositional arguments about historical redress, holocaust memorialization, or indeed the state of Israel, but rather through my great-aunt’s and my great-grandfather’s experiences – and my own.

I’ve been trying to give some weight to nostalgia, and its place in political thinking.

In doing so, I’ve been trying to give some weight to nostalgia, and its place in political thinking. Nostalgia, after all, is often written off as something that simply has no place in modern political life: it’s wrong, it’s irrational, it’s not serious. Yet it is my sense both that it has a place in politics whether we like it or not, and that there are ways in which the longings and desires represented within nostalgia can be legitimate for political thinking.

Writer and academic Svetlana Boym in The Future of Nostalgia explained that ‘nostalgia’ has two roots. The first is ‘nostos,’ meaning ‘return home’ – the element of ‘return’ is important here. The second is ‘algia,’ meaning ‘longing’. Hence nostalgia is, she writes, ‘a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. [It] is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy.’ No longer exists or never existed: it is an obsession with the irrecoverable, but one that we all seem to have had. It comes at us in ordinary moments of life, sometimes through music under an apple tree. Sometimes, though, it comes at us in its public political use.

The experience of nostalgia appeals to the realm of feeling. When the ‘nostos,’ the return home, is emphasized (instead of the ‘algia,’ the longing for something that may never have existed), it lends itself to romantic and pastoral nationalism, myths of blood and soil. This is no doubt what we have seen in Britain and the US. Farage’s Britain is one that is ethnically British, a people sprung from the earth. As The Black Atlantic author Paul Gilroy famously said, ‘There ain’t no black in the Union Jack.’ Donald Trump, of course, doubted Obama was really American, and spent the first months of his presidency attempting to suspend the refugee programme and to institute a ban on those from Muslim-majority nations. And all of this under the moniker of making America great again, a structure of desire that is explicitly nostalgic. He never has to specify quite when the ‘again’ is that he’s talking about, even while he’s claiming to restore it.

We in New Zealand are not immune from the desire for the return to the true home, either... I wonder if attachment to the way things weren’t is latent in Pākehā self-identification.

We in New Zealand are not immune from the desire for the return to the true home, either. In fact, quite the opposite: I wonder if attachment to the way things weren’t is latent in Pākehā self-identification. That sense that we’re all from small towns and organic communities which have sprung from the earth asks of settler colonialism that it never happened. And, as in so much of our earlier literature, we still seem to believe that putting labour into the land – shedding blood, or dying on mountaintops – is what makes it ours (ours as opposed to theirs).

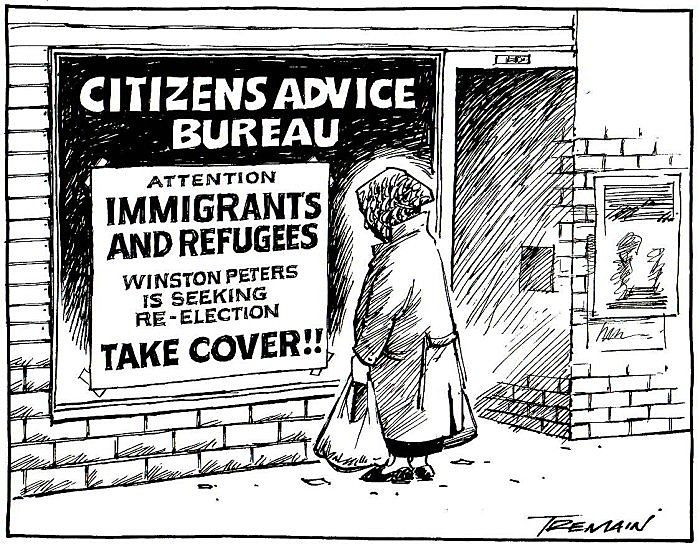

New Zealand politicians here have attempted to connect with the rise of nostalgia. The most explicit example of this is Winston Peters who has long made a career out of old politics, and is now touring the country speaking with renewed vigour. As ever, he is against immigration and in favour what he would call ‘integration’; he is against selling state assets and in favour of state intervention and industry protections. He offers, in short, much of what Muldoon offered: a time before the fall.

And then there is Gareth Morgan. His campaign slogan for his Opportunities Party is ‘Make New Zealand Fair Again.’ Of course, he’s attempting to channel Trump, albeit in a way that hasn’t exactly brought much of the country with him. Yet it’s notable that he believes that New Zealanders long for fairness, specifically a time when everyone in our country had a fair go at things. As with Trump, there are obvious questions that go unasked in this structure. When was New Zealand fair – and who was it fair for? Was it fair for women in the supposedly egalitarian 1960s? Has it ever been fair for Māori? Even if his party isn’t gaining much traction, there is a reason why he is attempting to connect his party with a vision of New Zealand’s past: it plays into the way so many of us imagine and experience politics.

Fantasies of the past are all over our politics at the moment... It’s what happens when our expectation that the future will be better than the present collapses.

Fantasies of the past are all over our politics at the moment, and this seems to have arisen out of all kinds of worries: the oncoming climate catastrophe, rising inequality, lack of access to quality public services, and the measurable decline of community participation. It’s what happens when our expectation that the future will be better than the present collapses.

The politics of nostalgia have also often been affiliated with insurgent, rather than established, political parties. I would think that this is because the political settlement of the last few decades has been explicitly committed (as Ruth Richardson emphasized to me when I interviewed her in December 2014), to unleashing ‘disruption’ and ‘creative destruction’ within the body politic. In this frenzied scheme of individual and social transformation, our attachments to certain social goods – community and the public, most obviously – are mere obsolete inhibitions, ones that need to be overcome if we are to achieve economic dynamism (a dynamism which is always just beyond the vanishing point). Our longings for connectedness, rootedness, and even for better lives, to say the least, haven't been able to find expression in mainline electoral politics.

The left in particular has not been able to articulate a robust political project that would be able to describe people’s struggles and their desires in a way that is meaningful to them, and to turn that meaning towards political change. On the one hand, there are the ahistorical, and largely technocratic, elements of the left: those who believe we are beyond ideology, and that the left should now be in the business of applying the data collected about the public’s views and preferences to political management.

More of the same, only a little different, isn’t speaking to people’s hearts.

In this view, the job of the political party is to offer ever-improved technical fixes on current political structures – this is government as a kind of science. This element of left thinking has not connected with the way citizens are experiencing politics through love, hope, hate, loss, grief, mourning, and melancholy – and often explicitly through ghosts of the past that walk among us in the present. More of the same, only a little different, isn’t speaking to people’s hearts.

On the other hand, as political theorist Wendy Brown pointed out, there is an element of the contemporary left that has, in her words, a ‘melancholic attachment to a certain strain of its own dead past, whose spirit is ghostly, whose structure of desire is backward looking and punishing.’ On the retreat for so long, this part of the left has become the traditionalists, standing up for settlements made, concessions won, and analyses performed during different economic and political moments. They have their own kind of nostalgia, and it looks a lot like Gareth Morgan’s ‘make New Zealand fair again’: self-evidently stuck in a fantasy structure of the past, and often shadowed by lament that things will never be the same again.*

Much of what I have said has been in response to the notion that the lid needs to be put back on politics, that there is no place in political reasoning for the very longings and desires we have recently seen in Britain, the US, France, Holland, and elsewhere. It is my view, besides everything else, that this simply is not possible. What we have seen has arisen out of a well-established and human way of making sense of the baffling, and affectively restricted political moment. Contemporary nostalgia calms the maelstrom of recent history. This way of knowing and feeling has become particularly appealing in the absence of left analyses that propose bold alternatives and are situated in contemporary struggles and forces.

Perhaps we need to understand how it is that we live among the 'algia,' the longing itself, which is always a longing for a world yet to come.

The question now, for us, is how the politics of nostalgia may become something other than discriminatory and narrow. This will mean thinking otherwise from the ghosts of the past that we have seen haunting Western democracies. It will mean requiring of politicians a more complex, reflective relationship with the past, and also a more fully articulated version of the communities and lives that we are seeking.

I suspect my great-grandfather would not really have wanted to go back to the shtetl. Rather than restoring the home of the past, the 'nostos,' perhaps we need to understand how it is that we live among the 'algia,' the longing itself, which is always a longing for a world yet to come. This is a much more difficult and unsettling task: we have nothing clear to return to. Perhaps it could be as unsettling as being given the name of home, in another language, which we can’t pronounce. Yet, in the place of the single origin or the absolute truth – in the place of Trump’s America or Farage’s Britain – we can, I think, view our longings and our losses as ethical and political challenges – not as retrospective but as prospective, and not as returns to a past home but as journeys towards a different future. What we call nostalgia can be a preparation for what is yet to come.

This talk was originally given at VicBooks in Wellington and Scorpio Books in Christchurch in late April 2017, where Andrew Dean was in conversation with the publisher at Bridget Williams Books, Tom Rennie, about nostalgia in contemporary politics.

Andrew Dean is the author of Ruth, Roger and Me: Debts and Legacies, published by Bridget Williams Books. The feature image of Frances provided by the Dean family.