Making Like a Forest: An Interview with Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror

How can we grow understanding as well as vegetables? Zoë Heine in conversation with two artists on their works in 'From the Ground Up' at The Dowse.

It starts [with|in] the ground

[we find worms | worms find us]

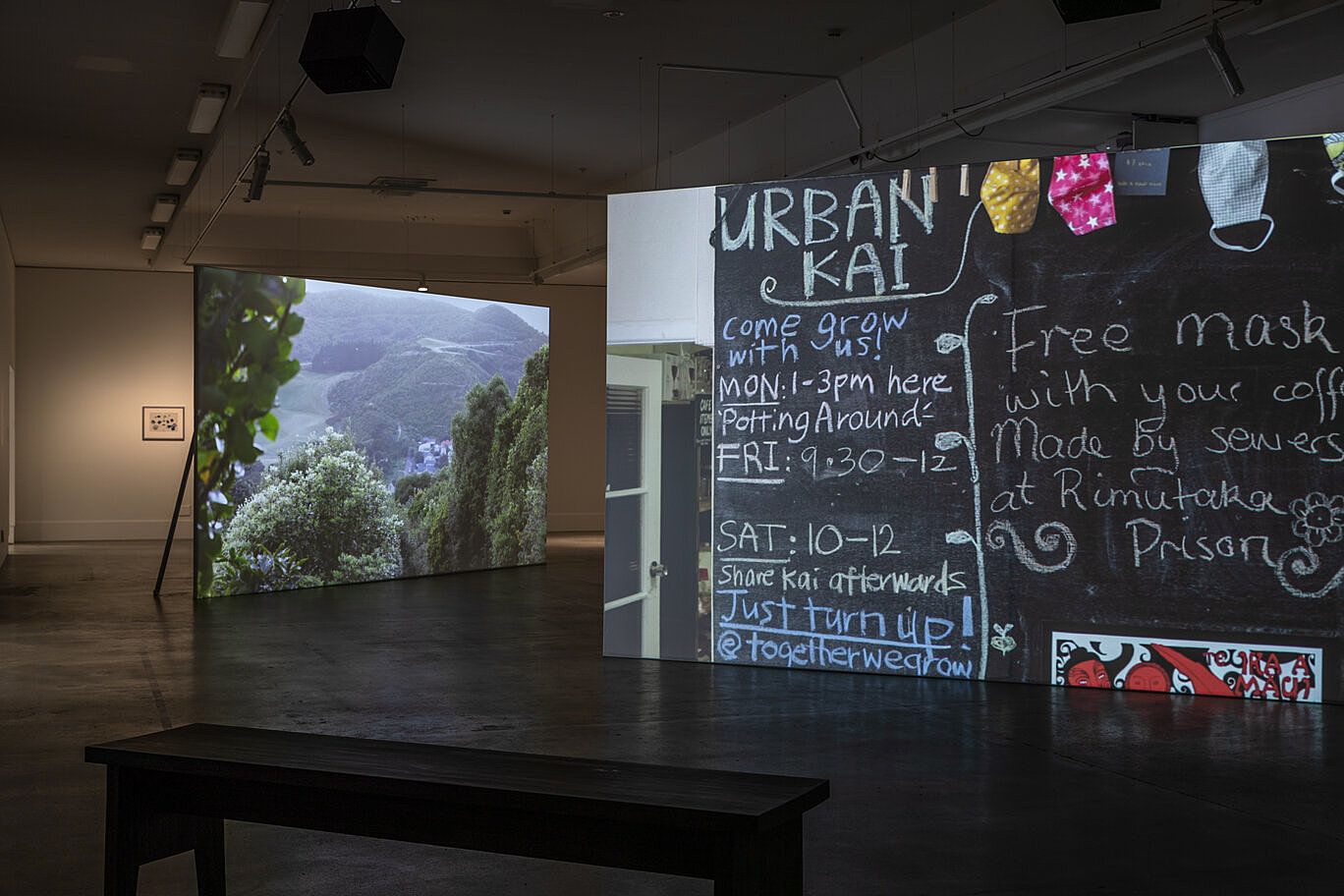

I sat alone in a room filled with the sound of worms squirming through compost, a chorus of rhythmic pops vibrating through The Dowse Art Gallery. From my perch on a seat, I can see Making Like a Forest: Common Unity Project Aotearoa and Manawa Karioiby Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror in From the Ground Up: Community Cultivation and Commensality. Xin and Adam are just two of the seven artists that contributed to this exhibition. They invite viewers of their works to slow down, to stop moving for just a moment and contemplate the connections between humanity and the many species we share this planet with. The works are gentle and thoughtful, inviting me to sit, watch and listen.

Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror, Making Like a Forest, 2020

In Common Unity Project Aotearoa humans and garden species are captured in motion at community gardens in Te Awakairangi. Manawa Karioi records the slow sway of forest species at a forest restoration project at Tapu Te Ranga Marae. I spoke with Xin and Adam before I visited this exhibition, so I was lucky that my experience came complete with comprehensive notes. In our conversation, Xin described the sound of the worms to me “as almost like a heartbeat”. Sitting here in the dim light, I begin to imagine it as such.

Xin considers the two artworks to be connected through food. Where Common Unity Project Aotearoa shows the cultivation of our food, Manawa Karioi, records a home and source of food for birds and other creatures, “Like growing a garden that lives for over a thousand years.” Continual shots are shown from each location. On the right worms churn through compost in the garden; to the left, a kōhūhū with purple flowers fills the screen in silence.

A recipe for generosity:

For good conversations

bring snacks.

Carrot sticks are good –

very versatile, easy to make.

Or even better, carrot cake

You’ll need: carrots, dates, coconut oil, rice flour.

A cake made possible

by species migration.

Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror, Making Like a Forest, 2020

I had arranged to meet Xin and Adam the day after the exhibition opened, at the Bond Street community garden, a tiny site in Te Whanganui-a-Tara CBD designed to “bring colour and energy” through the power of plants. Countless times I’ve walked past it, but never paused. This time, I was the first to arrive, so I attempted to make myself seen standing by a bollard at the Willis Street entrance. But as I contemplated the passers-by I felt exposed – streets are places to be in motion. Instead I retreated to the seats in the garden and here time slowed down again. Surrounded by wallflowers and rosemary, I no longer felt out of place.

Xin arrived on foot and we moved to Denton Park. I remember the park before it was rebranded – pigeons would try to steal my lunch, and everything was coated in their scat. It’s lush now and there’s a grassy knoll where I’m sure there used to be a flat space with rundown park benches. We positioned ourselves on the grass and waited for Adam.

Adam arrived, and when he was settled on the grass I asked them how they knew each other. They tell me they met at a reading group organised by Xin. It was a group designed to spark conversations over carrot cake, on how we connect to other beings on this planet. Nowadays, Adam spends two days a week at the Common Unity gardens in Te Awa Kairangi, and Xin has recently returned from Hamburg, Germany, where she completed her master’s. She now lives in Tāmaki Makaurau with her parents and a thriving worm farm.

a conversation on how mushrooms might be aliens from outer space

I was interested to know what it was like for Xin and Adam in getting the works ready for the exhibition. It was apparent it had been a marathon of creation, and they were exhausted. Then I realised that here I was asking them to keep creating thoughts and ideas, and I had brought no tea or food, or shelter from the cold breeze. It was an ironic failure of the principles of care and generosity, given the topic of their work. Yet Xin and Adam still brought thoughtfulness to each of my questions, in a conversation that ranged from learning to love intestinal worms to how mushrooms might be aliens from outer space.

The themes of the two works are built on Xin’s interest in resourcefulness and connections. “For me, it's a lot about operating in the cracks of capitalism ... these alternative economies and this kind of generosity and sharing.” Xin’s approach considers the garden as an architectural space for multiple creatures. The slow movement of slugs over rotting wood or the way a bee explores the intricate insides of a flower. She says, “Go to those leaves and look at them as though you are looking through the leaves. Then you see this very intimate space with many layers of green, and how it changes in the wind. I guess it's this certain kind of looking feeling, which if you are just walking by, you don't have access to.”

Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror, Making Like a Forest, 2020

As I watched the two screens, these words resonated with me. I tried to keep track of whose voice I was listening to and which species were being displayed, finding familiarity in the close-up shots of garden details; borage, fennel, broccoli, radish seedlings, slaters – species I could instantly identify and place. In contrast, the native species growing in Manawa Karioi were vaguer to me, although it felt like I should know them. My notes show scribbles of ignorance – was that a rimu or tōtara? I mused on whether a garden is a forest, or a forest a garden. But I suspect it might not matter – both are human terms for labelling complex entanglements of living beings.

Adam tells us of taking the compost out for his mum in the night and his flashlight illuminating the worms doing their busy worm business. For Adam, this moment revealed to him how worms have “just got this whole life that they live.” As I sat there, his remark had me wondering about the living worms far beneath me. In the dark of the museum foundations, is there a layer of soil with worms shifting around and making their popping vibrations? Are they singing and chatting to each other, far out of human sight?

Adam considers worms fantastic and friendly creatures. I ask him how he knows they are friendly, and he tells me, “They've never done anything that made me not think that. They wriggle and they eat things, they produce richness for everyone around them. I think they’re really aspirational.”

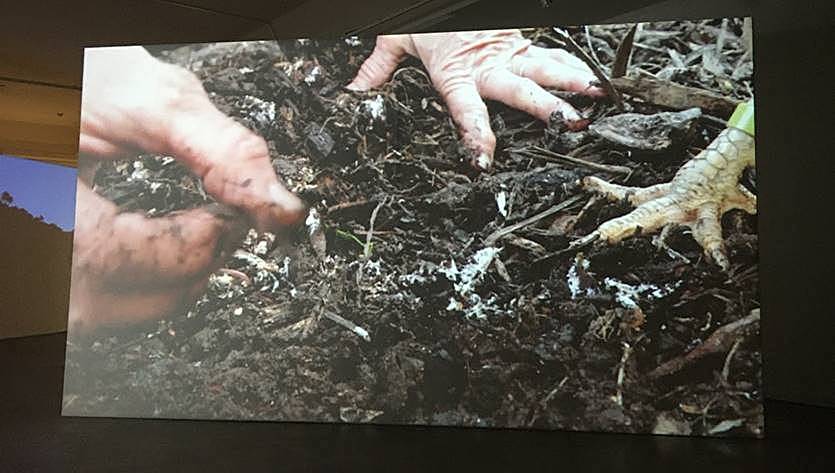

In the videos, the human presence is largely people’s hands. Hands that gather broccoli or prick out radish seedlings from seed raising mix. One of my favourite shots is human hands working alongside chicken feet – they rummage through the soil together.

Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror, Making Like a Forest, 2020

This act of putting our hands in soil has long been a way for us to connect to place. Adam tells us, “Pretty much every generation in my family, going back to my great-grandparents, has had to move to a new country for various reasons. It feels really significant for me to be touching, to be working with earth and plants.” I ask Xin if she considers herself a gardener and her answer reminds me of the need to be settled in place to tend to a garden. “I haven’t been so much, as I have been travelling or moving around, but I would love to start a garden.

Xin is interested in the way that hands and tools, claws and beaks transform the materials they work with and the hands as well. “The material changes us, and then we change the material.” The wider exhibition deals with ideas of food sovereignty and migration – who grows the food, and on whose land? Both concepts relate to the transformation of people and place through complex inter-species interaction.

The sounds of a blackbird in the garden recording reminds me that other species are not neutral players in human entanglement, even if they may be unaware of their own symbolism. Last year I came across an old newspaper clipping about blackbirds, who were brought to Aotearoa to remind colonisers of their faraway homes. The article finished with an explicit reminder, “May they thrive in their bloodless and unobtrusive mission of colonisation.” I realise I now can’t hear a blackbird without thinking about the history of how their (and my) ancestors got to this land.

“I suppose that’s the way we humans are, thinking too much and listening too little.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

In Ted Chiang’s short story, ‘The Great Silence’,an unnamed Puerto Rican parrot writes a letter to homo sapiens. The parrot ponders why we humans spend so much time searching for extraterrestrial life, and so little listening to the other species we share this planet with. With a soundscape built by bird calls, human voices and simply the wind in the trees, Xin and Adam’s artworks are a timely response to this.

we spend so much time searching for extraterrestrial life, and so little listening to the species we share this planet with

In Common Unity Project Aotearoa, a gardener retells a story of walking in the South Island. Sitting by a river when it starts to rain, they notice the drops creating a “deeply textured” space on the river surface – water meeting itself again. Taking shelter in a stand of mānuka, the gardener shares this intimate moment, “I could hear a sound coming from the plants as if singing.” I’m reminded me of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s description of standing in a cedar forest as the rain comes down in Braiding Sweetgrass. “I don’t want to just be a bystander to rain, passive and protected; I want to be part of the downpour, to be soaked, along with the dark humus that squishes underfoot … I want to feel what the cedars feel and know what they know.” Kimmerer encourages us to pay attention to our environments, “to acknowledge that we have something to learn from intelligences that are not our own.” Her work brings together the ideas of care and kinship, two concepts raised as significant in the gallery wall notes for Xin and Adam’s works.

Common Unity Project Aotearoa finishes with a story about a goat who helped overcome the initial mistrust that parents had towards a Common Unity garden project on a school field. It’s a clever thread that combines the central tenet of the show; that connections between humans and other species build kinship and community. I wonder why we as humans struggle to communicate within our own species. Why is it easier for us to trust a goat than another human? Perhaps there is a simplicity in our interactions with other species that is free from the complex violence of human history – violence present in the soil of Aotearoa and made manifest through colonisation.

In the act of resistance, Indigenous peoples throughout the world continue to live in relationship with ecosystems. In Manawa Karioi, a voice tells of how they only gather rongoā when Tāne Mahuta gives them permission. Adam shares that while Manawa Karioi may need humans to care for it, the reverse is also true. He recounts a conversation with Dean, the son of Bruce Stewart (founder of Tapu Te Ranga Marae). “When we were talking to Dean … he was talking about manaakitanga. We asked whether he thought that he was kind of tending, if he was extending manaakitanga to these other beings. And he was like, no, it's the other way around. They're the owners, they are extending the welcome to us.” The challenge set by Making Like a Forest: Common Unity Project Aotearoa and Manawa Karioi, and more broadly by From the Ground Up, is for more and more of us to recognise and accept this act of generosity, and to repay it in kind with respect and reciprocity.

From the Ground Up: Community Cultivation and Commensality

The Dowse Art Gallery

24 October 2020 — 7 March 2021

.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Feature image: Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror, Making Like a Forest, 2020