Loose Canons: Nancy Brunning

Writer, director and performer Nancy Brunning digs into her past and the heart of her work.

Loose Canons is a series in which we invite artists we love to share five things that have informed their work. Meet the rest of our Loose Canons here.

Nancy Brunning is a renowned actor and director of theatre, film and television. Since her award-winning performance in Briar Grace Smith's 1992 play Ngā Pou Wahine, Brunning has been a leader in kaupapa Māori productions, directing te reo Māori productions for Taki Rua, working a alongside Taika Waititi on the Oscar-nominated Two Cars, One Night and launching Hāpai Productions with Tanea Heke. Brunning is the director of He Kura E Huna Ana, opening at BATS in Wellington on June 12 before touring to Tauranga, Gisborne, Auckland, Hamilton and New Plymouth.

I moved to Wellington at the age of 18 to train at Toi Whakaari Drama School. I am so grateful to Sunny Amey, the director of the school at the time, who fought to get me in there. I moved to Auckland after graduating to pay off drama-school debts working on Shortland Street for two years (the original Jaki Manu – Tania Gilchrist – chose to follow her new young family to Wellington and I got cast by default). From there I returned to Wellington and worked mainly in Māori theatre in Wellington and was fortunate enough to land a couple of film roles such as What Becomes of the Broken Hearted, Crooked Earth, most recently Mahana.

I began writing for theatre in 2011, co-founded Hāpai Productions with Tanea Heke in 2013, produced my first play Hīkoi in 2014, and then again in partnership with Auckland Arts Festival in 2015. We have just recently finished presenting Portrait of an Artist Mongrel – Rowley Habib at the Auckland Writers Festival. At Kia Mau Festival I am directing He Kura E Huna Ana by Hōhepa Waitoa for Taki Rua Theatre Productions and I will be presenting draft one of play number two at the Tawata Productions Breaking Ground Festival 2018.

I knew at the age of 15 that Māori theatre was what I wanted to do for a living. I believe this medium can communicate to our people on many levels – visually, aurally, emotionally, intellectually, verbally. I thank Tungia Baker, Wi Kuki Kaa, Rona Bailey, Bob Wiki, Rowley Habib, Don Selwyn and Keri Kaa for creating and establishing a Māori theatre industry for us. I was very lucky to have arrived on the scene during their time here and experienced and learned the kaupapa for their Māori theatre vision in the New Zealand industry. He mihi aroha tēnei ki te hunga mate, piataata mai i a Matariki, ko koutou ngā whetū tūturu. Ki te hunga ora, whaia te aroha i ngā wā katoa. Mahi tonu, mahi tonu, mahi tonu.

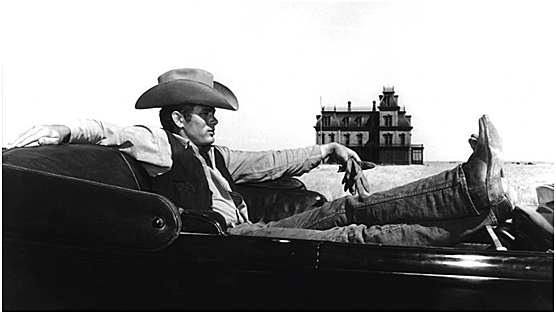

James Dean

I was 11 or 12 when I first read about James Dean. I was actually in love with Matt Dillon and would read any article I could find about him. Matt Dillon was part of the 1980s group of up-and-coming starlets know as the Brat Pack (the then-modern equivalent of the Rat Pack, who were the likes of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr.). The rest of the Brat Pack was Ally Sheedy, Judd Nelson, Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez, Demi Moore, Rob Lowe, Chad Lowe, C. Thomas Howell, Ralph Macchio. They portrayed the awkward, reckless, emotional, dramatic and dangerous teens in classic films like The Breakfast Club, Rumble Fish and my favorite, The Outsiders. On a trip home from Ōtaki I had acquired a magazine with an article on Matt Dillon. The article described him as the James Dean of the 80s film era. I thought ‘what?’ Matt Dillon is a version of this guy James Dean? Who’s this guy? There’s a picture of James Dean – a light-haired version of Elvis.

Without internet you had to go to the library to research any favorite movie stars, or do what I did, wait for an entire two years and stumble upon information about him by accident. I was part of a theatre troupe in Portugal performing with 24 other countries and on our travels we go through Europe. I’m still in love with Matt Dillon but everywhere there’s memorabilia of James Dean. I read up about him. I find out he’s made only three movies in his life and dies a tragic death at 36. I buy posters and reprinted photographs of him, take him home and plaster him all over my walls. I watch his movies, East of Eden (his performance changed the way acting was approached in film), Rebel Without a Cause (the character defended the underdog), Giant (he went method on this one). He rocks my world. I mourn for him. (Mō te whakameamea! So dramatic.) I have fallen out with Matt Dillon and in with James Dean. When I applied for drama school, I imagined that I would be acting just like James Dean.

Being in the middle

I was the second youngest of seven children and was born after the only boy and before the baby of the family, both of whom were considered ‘special’ children. I refused to give up my baby privileges and still have memories of ripping the bottle from my little sister’s tiny baby lips, shoving the dummy into my fat mouth and draining the milk faster than my little sister could gasp and wail.

My dress sense was influenced a lot by my brother – I looked like a boy and strangers called me ‘son’ a lot. I had regular unprovoked fights at school because of my then-androgynous appearance. I think boys were so confused about me they had to punch me to make sure I wasn’t a guy. I became devious – my parents would be preoccupied with their demanding ‘special’ children while I, alone, would play behind the shed, starting grass fires (that I could put out myself).

At about 11 years old, while at intermediate, we did a drama exercise where settlers arrived in New Zealand and encountered the Māori. We could decide which side we wanted to be on. My best friend since primary school was a Pākehā girl and I followed her onto the white-settler side, and pretended I didn’t like to get my feet wet and spoke posh. We were directed to sit opposite each other, the settlers and me face-to-face with the Māori. We were encouraged to talk about what we knew of each other. My Māori side said white people were rich, that they drank tea out of cups and saucers and wore too much makeup. My Pākehā mates laughed and countered that they’d never drunk tea from a cup and saucer, wearing too much makeup would label them as tarts and they didn’t think they were rich. I couldn’t defend my settler status, because I didn’t have a clue. My Pākehā settler side said what they knew of Māori. Māori were lazy and not very good at school and were dole bludgers. I looked at my Pākehā mates, shocked that they thought Māori were those things. For the entire exercise I became silent and voiceless. It made me feel sick. I later realised that being in the middle is at the core of my writing.

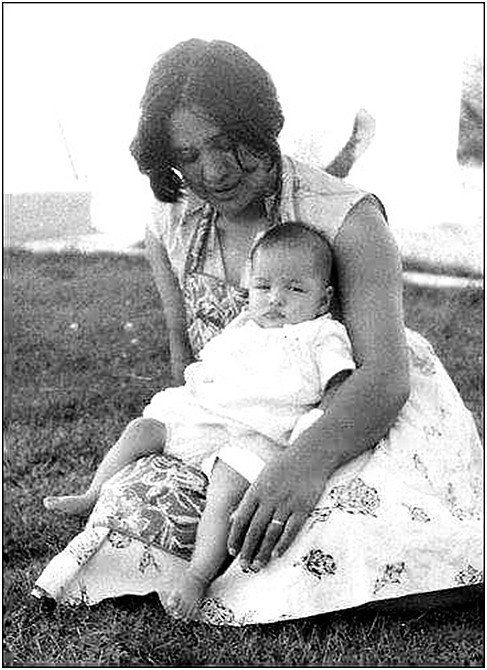

My mother and father

The older and more educated I became about the deep and often disturbing history of colonisation of Māori in this country, the more I began to see my parents in a different light. Both my parents were also stuck in the ‘middle’ of something. My father was Chinese/Māori and growing up with that lineage meant you had to learn a whole new set of survival techniques. My mother was plucked from home and fostered by a family that believed beating the Māori out of you at home and school was the best thing for a child under 10. Dad is from Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga (Ōtaki, at the head of the fish) and my mum is Ngāi Tūhoe (Ruatāhuna, the heart of the fish). My parents met in Ngāti Tūwharetoa territory (Taupō, the puku of the fish). They were either lured or stolen away from their papa kāinga through policy, carrying with them their burdens from the past.

They married, had children and raised us in Taupō. There they created a peaceful life, where you did things humbly, almost to the point of submission. The majority of my siblings were written off at school. Rather than fight the school system to give her children a better education, my mother preferred to support my older siblings when they could leave school and find them jobs as soon as she could. My dad worked, travelled, building houses all around the country. He worked a lot in isolation. Sometimes we’d get piled up into the truck with him and spend a week by the beach while he was building.

Both my parents were quiet people unless their families or friends came to visit and suddenly the house exploded with life. I often think about everything they kept hidden deep inside of themselves and how their lives could have been if they were truly able to be themselves. To be Māori or Chinese, to speak their own language, to freely practise their own culture. Being their true selves. Being free. My parents’ lives and experience, and the experience of that generation of Māori in this country is something that I want to continue to acknowledge either through creating characters or when writing.

Rangimoana Brunning and Grace Jones

My sister Rangi influenced my music taste. She introduced me to Prince, Michael Jackson, Fun Boy Three, Madonna, Tom Tom Club, Flock of Seagulls, Third World, the Pointer Sisters and Janet Jackson. More importantly she introduced me to Ricki Lee Jones and Grace Jones. (I have a poster of Ricki Lee in the office at hau kāinga.) Every morning I would ‘borrow’ her records when she was at work, take them to intermediate and play them on the hall stereo to all of the kids hanging out before assembly. My mum had passed away a year earlier and music became my consoler, my liberator. I connected to other cultures through music. I could see how these cultures through their music survived in Pākehā society. I could see how culture through music could be elevated to a different plane…ladies and gentlemen – Miss Grace Jones…

I saw Grace Jones’ concert in Queenstown this year. It was without a doubt the best live concert I have ever been to. She is my goddess divine. All I kept thinking when I watched her was how powerful she is and she is 69 years old. If I could perform with a quarter of the power she performed at, that night? My live-theatre-experience zone-out would never be the same for me, ever again.

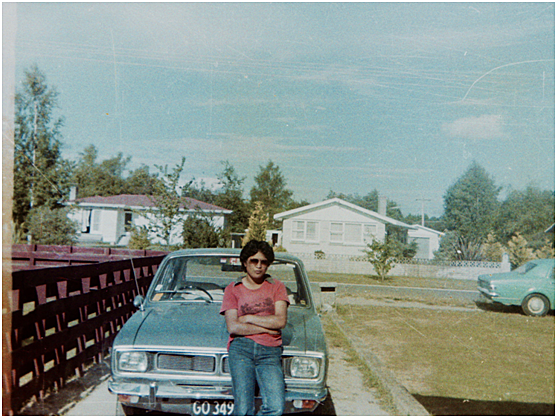

My siblings

I have grown up surrounded by girls and a brother. I love, love, love my sisters to death, but in my youth, being raised with a bunch of them was full on, man! The emotion and energy that flew through our home on any given day was intense. My introversion, I believe, began when I resolved to “not compete with them, but to learn from them.” Every trick they played and failed at, every rule broken, every lippy remark, every chore not done, every lie and broken item that was left unclaimed; I observed, very closely, their techniques and concluded to never do it like that.

Every morning our household must have sounded like a murder-house – with sisters who knocked you out if you took too long in the bathroom, a sister who burned the porridge while day-dreaming and all the other sisters would attack her because breakfast was ruined. Sisters who had screaming fits at the hairbrush that would not comb through their bushy mop and sisters who did not tolerate cheek, and would chase you around and around the block until your body cramped up and collapsed to the ground and you were dragged back home to face your crimes. But then on the other hand you had your sisters who never used up all the water in the morning, who could cook porridge, who knew how to French braid your hair, and chased the bully-boy down the road until he cramped up and collapsed to the ground and was made to face his crimes. Who needed drama school when you had access to that material every morning for 18 years? Some days my silently suffering bro and I would run away from them. My brother liked to climb onto the shed roof and jump off it for fun. Did I say, I used to play behind the shed, lighting grass fires I could put out myself?

He Kura E Huna Ana will play at:

BATS Theatre, Wellington from 12th-16th June

X Space, Baycourt, Tauranga from 19th-20th June

War Memorial Theatre, Gisborne on 22nd June

Herald Theatre, Auckland from 26th-30th June

Gallagher Academy Space, Hamilton from 2nd-3rd July

Theatre Royal, New Plymouth on 5th July

Click here for full details.