Internet Histories | 9 December

This fortnight: speculations on whether we're about to see the end of New Zealand's foremost literary journal, the snark vs smarm debate and New Zealand's weirdest pyramid scheme yet.

This week on the Internet:

The end of Sport? | Smarm v Snark

Realstew, New Zealand's weirdest pyramid scheme yet

Will

For some reason, Creative New Zealand has decided to stop funding Sport(the literary magazine, not the social physical activity). I write “for some reason” because it’s still unclear why the decision was made.

Victoria University Press publisher Fergus Barrowman puts Sport together, and has done so for the last quarter of a century. He tweeted last Thursday that CNZ had told him Sport’s latest application for $5,000 had been denied because of “missing detail and confusion in budget information”.

Considering that CNZ has been funding Sport throughout its 25-year existence, and that Barrowman maintains he didn’t fill out his forms any differently this time round, it all seems a little strange. And it seems even stranger when CNZ’s public statements (okay, tweets) have said that, on the contrary, it was the strong competition which left Sport empty-handed this round.

Re Sport -stronger applications this round so unfortunately Sport unsuccessful this time. We're talking to Sport about applying in Jan.

— Creative New Zealand (@CreativeNZ) December 5, 2013

So which reason was it? And does it matter anyway?

New Zealand writer types learning of Sport’s apparent fate have, unsurprisingly, been quick to express their unhappiness with the prospect.

So Creative New Zealand, NZ's govt-funded arts agency, has just killed the country's leading literary magazine?

— Bill Manhire (@pacificraft) December 4, 2013

Funding withdrawn from the literary journal SPORT means a huge loss to our culture. http://t.co/v3K1varNMc

— Emily Perkins (@EmilyJPerkins) December 5, 2013

I'm really disappointed to hear that Creative NZ has withdrawn its support of SPORT. The wrong decision, whatever the rationale.

— Eleanor Catton (@EleanorCatton) December 5, 2013

But none of this matters, of course, unless you think publications like Sport are worth having/saving in the first place.

An article published last month at Overland and The Guardian begins to address this question in the Australian context. Jeff Sparrow, in response to another article by Robyn Annear in the The Monthly, accepts Annear’s allegation that there are just not very many readers for this sort of thing:

Literary magazines do not reach a mass readership. Then again, neither does literature.

But he then goes on to argue sensibly that this is not really the point, and neither is the fact that literary mags don’t turn much of a profit.

What he never gets to say, however, (and what must really be at the bottom of this issue) is that you’re only ever going to be convinced of the importance of literary magazines if you’re convinced of the importance of literature in the first place.

A recent New Yorker piece takes a look at two recent psychological studies that might convince even the non-book-loving type that literature and literary culture are useful. The studies seem to provide evidence that reading – serious reading –can make you more empathic.

Perhaps it is appropriate, in our moment of ardent quantifying—page views, neurobiological aperçus, the mining of personal data, the mysteries of monetization and algorithms—that fiction, too, should find its justification by providing a measurably useful social quality such as empathy.

This is all well and good, Lee Siegel writes, but why should literature have to be useful in the first place?

Fiction’s lack of practical usefulness is what gives it its special freedom. When Auden wrote that “poetry makes nothing happen,” he wasn’t complaining; he was exulting .

Rosabel

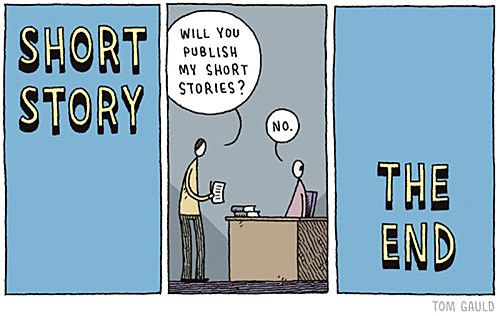

[caption id="attachment_8466" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Illustration by Tom Gauld; Sentiment by Creative New Zealand[/caption]

I want to comment quickly on whether publications like Sport are worth having in the first place. Short answer: Yes. Long answer: Yes, and in a country like New Zealand, the decision to stop supporting a journal like Sport isn't just baffling, it's disheartening.

Literary journals are rarely profitable ventures, and one that consistently and tirelessly works to showcase new writers in a small country is basically guaranteed to operate at a loss. It's a testament to the reputation Sport has established that it's managed a meagre profit in recent years (and only then with the support of CNZ), but its real value lies in giving talented writers an opportunity to see their work in print. Not only because it gives previously unheard voices a mouthpiece; not only because it's exciting and invigorating for both writer and reader; not even because each issue acts as a sort of anthropological record, preserving the landscape of our literary scene at a given time, but because it’s an essential part of the cultural ecosystem.

Being published is a practical and necessary step to climbing the authorial ladder. You can try to apply for a grant, or a residency, or pitch to a publisher without having had anything published elsewhere. You can.

But Sport acts a bridge between being alone in your bedroom with a hard drive full of sad poetry about friendly bodybuilders and their tiny pugs and being alone in your bedroom with a published book of that poetry. When you remove scaffolding like this, you hinder growth and evolution. See also: scores of 8-bit lemmings cascading serenely off a cliff.

That’s not to say there aren’t other literary journals in this country - we're lucky to have publications like Hue & Cry, Landfall, takahē and JAAM – but Sport is the best we have. It’s also worth mentioning that they pay. Not heaps, but more than other journals, and by the page instead of a token flat fee. For many writers, it'll be the first time they've been monetarily valued for their work. I know that's not why people write, but it is how writing should be valued (and the fact that 'at all' is an acceptable benchmark here says a lot).

*

Last night was the fourth edition of Twitter Poetry Night NZ, a brilliant project run by Ashleigh Young where people record themselves reading poetry. There's a certain magic to seeing each poem assemble here, like sand rushing across the dunes or a single creaking, collapsing raincloud:

[caption id="attachment_8484" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Storm over Colorado[/caption]

Joe

Ever had an argument on the Internet? Got upset at a bad review, or sneered at a good one? Responded to criticism by talking about how people have lost the faculty of common decency? If so, you might be on one side or the other of the new culture wars - over at Gawker, Tom Scocca has devoted a lengthy essay to the pitched battle unfolding between the noble forces of 'snark' vs the establishment's 'smarm'. Reading through for the second time, I'm proudly riding shotgun alongside Scocca for everything he takes aim at: Buzzfeed, PR consultants, Joe Lieberman (in NZ terms, a Peter Dunne who could not get over the intoxicating smell of his own shit), Niall Ferguson - but I feel like he's giving lazy and thoughtless responses (short and long) a sort of ideological baggage they don't have. 'Snark', he insists, is the last weapon of the dispossessed, the legitimately angry, the underdog critics who will not bow. 'Smarm' is the tool of the neo-liberal hegemon, at once wielded to force Upworthy-style headlines down our throats and implement policies to quietly eliminate the homeless.

Leaving aside leading snark proponent Gawker's backing by a modest community co-op media company worth $300 million - leaving aside the fact that I can't stand glib clickbait positivity anymore than the next broke writer - I just don't believe snark and smarm don't have the particular couplings to prestige and privilege that Scocca says they do. You can heap venom on low-level offenders, beneficiaries and the undeserving poor with a bile that could corrode titanium, you can smarm at the top of the Twitter heap about a 'highly probematic' turn of phrase with the best of them. There's a whole bunch of different power relations in which these tonal devices are interchangeable, but with both, it often comes back to serving the writer or speaker and his or her own, rather than the subject.

Weirdest part is where Scocca demonstrates how smarm detracts and distracts from Edward Snowden's situation - smarm is saying Edward Snowden is a traitor, or a self-seeking narcissist, or a naif who betrayed secrets without recognising the consequences - suggesting that snark is a beacon of righteous clarity. But plenty of stuff I'd qualify as snark - sharp and biting digs at Snowden's weird Atlas Shrugged/Ron Paul libertarian streak, at the way that this and the GCSB was overwhelmingly a middle-class white person concern - didn't exactly cut to the essential truth either. At this stage, snark is 'an angry or sarcastic thing I agree with', smarm is 'a faux-earnest or passive-aggressive thing I don't'. This is an interesting theory (and whether you like your bullshit served to you neat or on the rocks is another great question) but it's rubbish semantics.

Snark or smarm - they're both ultimately a failure to put ego aside, and they usually imply a disregard or lack of consideration for a work, an argument, whatever - because it's more important to get in first and get in fatally (hattip to Rosabel for this great observation). The framing device of 'On Smarm' is the Anakin Skywalker-like figure of Dave Eggers, who abdicated a life of 'incredibly snotty, hostile articles attacking big name, non-fiction journalists' to become an insufferable Zen-like figure of moderation who sagely counsels our youth not to discuss a book until they've written one. But really, he just proves a more basic reality - that a pathological egotist will eventually find the right tool to get himself success and attention, whether it's more vinegar or more honey.

Hayden

The recent Roast Busters scandal and subsequent media frenzy shone a light on some of the awful human behaviour that can thrive at the intersection of rape culture and social media, much of which poses serious questions of our society. But the most bizarre thing it brought to light - by way of a journalist doing a bit of background on one of the perpetrator’s dads - is RealStew, ‘a revolutionary step in the way the world communicates and interacts’, developed right here in New Zealand.

RealStew, like so many internet start-ups, seems to have been funded and built entirely on the back of lofty, meaningless rhetoric. But what makes it so much more intriguing is the amateurish, ragtag nature of the thing. Where you might usually expect such a start-up to at least have an agency-polished veneer atop the bullshit, RealStew seems to have called on the best in-house skill milling around its Parnell offices.

The result is a brand identity made up of animal stock images, word art and promo videos - featuring Anthony Ray Parker - that include bizarre scripts and Tim and Eric-style animation pitched in a strangely melancholic tone. The website itself looks as if it came on a complimentary CD-ROM that shipped with Windows 95, and many of the applications don’t even work yet.

And the name! Which is apparently an acronym for

Ripple Effect

Empowering

Abundance

Life Changing

Sharing

Transparency

Energy

Wealth

There is absolutely nothing that’s not weird about it. Which is why the first reaction most people have when encountering it is ‘this can’t be real’.

But it gets even better, because the more you try to decipher the bullshit and figure out what RealStew actually is, the more you realise the entire thing is seemingly some sort of cultish pyramid scheme, where members can somehow, through a mathematical formula based on the six degrees of separation, share in the profits generated when other members click on advertising within the site.