Internet Histories | 8 July

This fortnight: the absurd new Superman movie, vertical cemeteries, films reviewed like video games, naughtiness in award-winning fiction and racism in the US.

This fortnight:

Man of Steel | Vertical graveyards | Censorship in literature |

Incidental legislative racism

Jose

I’d been dreading it for months. With brow furrowed, I’d stand at the kitchen sink filling the dishwasher letting rip with a fustian diatribe laying down my concerns and fears to my girlfriend - possibly within earshot it didn't matter. Surprisingly, I’d started by salivating and savoring the anticipation.

Holy shit, I was pretty into that. Ignore the fact that regardless of the pre-release buzz I’d be seeing the film anyway. The trailer could have featured Supes and Owen Wilson slap sticking their way through an internship at Google and I’d still pay for a ticket (that’s just how thirty four year old boys like myself operate). But this looked fantastic: a rousing Hans Zimmer score, weird krypton stuff, intense flying fighting stuff and bombastic destruction which would no doubt test Superman’s vow to protect humankind.

The glow from the flurry of trailers and TV spots remained for a few weeks. But then it started to ebb as previews and reviews came in. I took a good look at myself and dived in, spoilers be damned. “Joyless” said one review. “Sour and cynical” said another. “Michael Bay” was thrown into the mix as well. The guys at Red Letter Media reamed it, mostly just shaking their heads and responding with gallows humor like traumatised paramedics.

Effectively the problem is hence [spoilers]: during the film, in which a group of criminals from Superman’s homeworld attack earth (the MacGuffin is Superman himself, in a convoluted and contrived twist), huge areas of urban and rural America (and the Indian Ocean) are destroyed in a sustained cinematic barrage of explosions and shattering skyscrapers. The death toll must be in the millions, looking closely one can see bodies flung like chocolate sprinkles every time something goes boom.

The film’s plot has Superman on the other side of the world dealing with one part of the baddies’ plan, while the US military deals with the holocaust in Metropolis. There is no reason given as to why the guy who can fly at the speed of light isn't where he could be saving the most people, which arguably is what you want to see in a Superman film.

Finally, Supes and Lois meet in downtown Metropolis which is a smoking hole, and, inexplicably, they pash while a fine white ash which used to be four million people settles around them. And that’s just foreplay to the finale where Superman snaps Zod’s neck and then starts screaming.

As you’d expect Man of Steel has been discussed widely on the internet. Some, like comic book writer Mark Waid (his work retooling Superman’s origin in 2003’s Birthright influenced some of the better parts of the film), had serious problems with the movie. Waid put it succinctly after going into some detail:

Once he puts on that suit, everyone he bothers to help along the way is pretty much an afterthought, a fly ball he might as well shag since he’s flying past anyway, so what the hell. Where Christopher Reeve won me over with his portrayal was that his Superman clearly cared about everyone. Yes, this Superman cares in the abstract–he is willing to surrender to Zod to spare us–but the vibe I kept getting was that old Charles Schulz line: “I love mankind…it’s people I can’t stand.”

Compare this with the latest Fast and Furious film: In one scene both Vin Diesel's character Dom Toretto and his crew of funkily diverse road racers put themselves directly in harms way to draw the attention of the bad guy in a tank (don’t ask) away from innocent bystanders. (What in God’s name is happening when Vin Diesel is more heroic than Superman?)

It’s not merely the violence; there are ways to have city wide destruction and a badass Superman without making your inner child die. The Justice league Unlimited cartoon managed to examine themes of power and corruption as well as offering the traditional superpowered slugfests.

It’s the Battlestar Galactica effect. The new TV series took a hokey old tv show that revolved around shiny robots and Dirk Benedict’s hair helmet. Rejigged by show runner Ronald D. Moore it became a platform to explore moral ambiguities, religion and what it means to be human. The Justice League cartoon spend a whole season with a Superman fighting self-doubt after watching a mirror dimension version of himself take over the world and turn Lex Luthor into chilli sauce with his heat vision, all to, supposedly, protect the world.

The people behind Battlestar Galactica and the Justice League cartoon have taken two creaky and fairly silly genres (space opera and superheroes) and used them to tell stories about the world by reflecting our insecurities and foibles. But ultimately they both are hopeful: despite distrust and hatred Galactica finds its way to Earth and Superman rejects murder and totalitarianism.

This is all important because we make sense of this world and each other through the stories we tell. I’m not arguing for sanitised, happy-clappy media for kids: Children need scary or slightly dark stories to to teach them about the world and to make them well rounded human beings. They also need to learn how to tell their own stories, so it’s vital what they watch, read and hear is as well crafted as possible.

That brings me back to Man of Steel. There’s a lot you could say about it: how its plot holes could be forgiven if it was simply just fun to watch or how films nowadays seem to insist on telling you about its characters rather than showing you. But perhaps the most damning thing I could tell you about Man of Steel is that it’s a Superman film I wouldn’t feel comfortable taking an eight year old to. And I’d tell you how depressed that makes me feel.

Matt

Where do you go after you die?

The sack of flesh you leave behind, I mean. Despite the richness of human culture, we’re pretty vanilla when it comes to chucking out corpses. I guess there are only so many ways of saying goodbye that aren’t grotesque parodies.

The ceremonies we do have are grotesque in their own ways, though. Embalming involves hollowing the organs out of people's bodies, then filling the leftover husks with toxic chemicals that make them look sleeping. Cremation makes a lot of sense, if you’re not skeeved out at the thought of accidentally inhaling your loved one. Burial takes up a heap of land and resources that might be better enjoyed by people who aren’t dead.

I’m actually a big fan of cemeteries. They’re quiet and well-tended oases of calm, and often bear interesting historical information on tombstones and plaques. Still though, they take up a huge amount of space, and people keep on dying. It turns high-density living is the new trend in dying.

Like other communities that bury their dead, the Baha’is of Mumbai are fast running out of burial space. Their community might be a small one—around 500 in the city—but they are aware that the two graveyards are no longer enough. In 2004, after they were unable to secure more burial land from the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, the Local Spiritual Assembly (LSA), the elected council of Baha’is in Mumbai, passed a decree whereby two bodies are to be buried in a single grave. So now, bodies are buried in concrete and stone vaults with partitions. In 2008, they realised that even this was not enough. So a new decree was passed—each new grave will have to house three bodies.

…

In fact, there are no permanent graves available in Mumbai. Both in Protestant and Roman Catholic cemeteries, bodies are buried for two years, after which their graves are reused. The bones of previous occupants are exhumed, and either stored in ‘niches’ (small shelf-like vaults in cemetery walls), or, if the family is unable to afford a niche, cast away in a bone well, a tank-like structure that stands within all cemeteries.

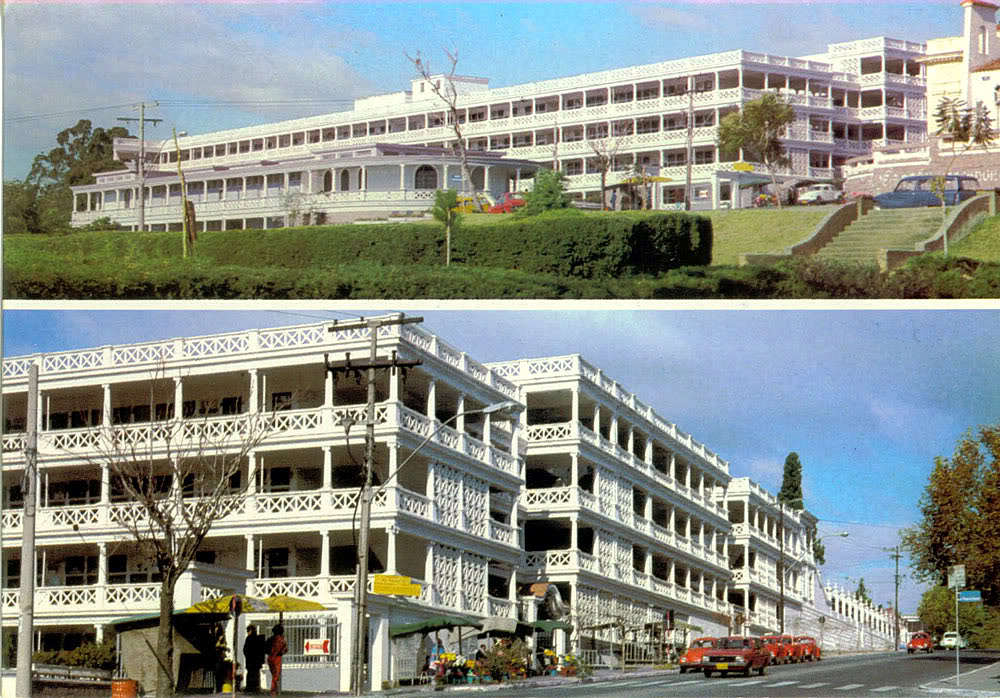

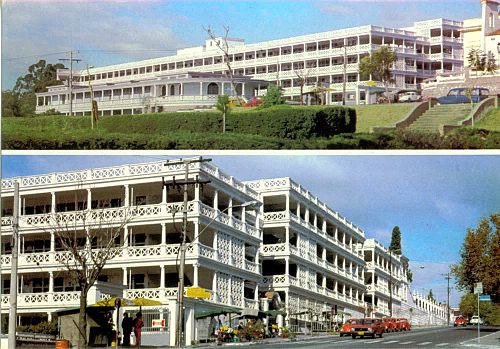

This is a problem people have been thinking about for a while. The fantastically-named ‘necropole’ is a type of vertical cemetery in Brazil:

The Memorial Necropole Ecumenica is the tallest cemetery in the world. The first building Memorial Necropole Ecumenica 1 was built in 1984, with Memorial Necropole 2 following later that year. Though not Brasil's first multi-storey cemetery, perhaps it is the one most ahead of its time. As the brain-child of Jose 'Pepe' Alstut it was not only conceived of as a solution to the lack of space in the cemeteries of the region but also as an attempt to demystify the macabre of the typology.

I love the idea of the architecture of a cemetery assisting the understanding of the process of death itself. It’s something we don’t like to think or talk about, but death is kind of the most important thing in the world. In 2011, ‘The Tower for the Dead’ won an honorary mention in a skyscraper design competition. But it’s not exactly a type of skyscraper.

As existing cemeteries grow denser the design team imagines that great shafts will be the next logical phase. Therein bodies can lay to rest deep under the earth, but still have markers assessable to visitors. The Tower of the Dead is not just a repository, but an architectural expression of the grieving process. Large ramps spiral down the main light shaft, allowing visitor to immerse themselves in the 5 stages of the grieving process and come out with resolution and acceptance of their loss.

Necropole. What a word.

*

I play a lot of video games, so necessarily read a lot of video game reviews. I didn't realise how deeply I'd been conditioned to expect hackneyed crap until I read this film review in the style of a video game review. As someone currently writing a thesis dealing in part with the transformative power of digital culture, and video games specifically, I find it real galling when they're referred to as a trashy or second-rate narrative medium. But with throwbacks like the current review ecology, maybe it's no wonder.

Bronwyn

You’ve probably noticed that there’s been a bit of a kerfuffle recently over a book featuring naughty words winning a significant literary prize. It’s easy to write this off as a way to sell newspapers, or a predictable response from the self-appointed moral police, but that’s to ignore the real effect this has on people making this work.

The books of Judy Blume were once considered to be of dubious moral standing, and the impact of this led Ms. Blume to become a card carrying member of the anti-censors. Her introduction to a book of writing by authors who have had worked banned is on her website, and it’s definitely worth a peruse.

I wrote Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret right out of my own experiences and feelings when I was in sixth grade. Controversy wasn’t on my mind. I wanted only to write what I knew to be true. I wanted to write the best, the most honest books I could, the kinds of books I would have liked to read when I was younger. If someone had told me then I would become one of the most banned writers in America, I’d have laughed.

When Margaret was published in 1970 I gave three copies to my children's elementary school but the books never reached the shelves. The male principal decided on his own that they were inappropriate for elementary school readers because of the discussion of menstruation (never mind how many fifth- and sixth-grade girls already had their periods). Then one night the phone rang and a woman asked if I was the one who had written that book. When I replied that I was, she called me a communist and hung up. I never did figure out if she equated communism with menstruation or religion.

On being questioned by her (long standing, trusted) editor about the content of a book, and deciding to remove two sentences, much against her better judgement, she says:

What effect does this climate have on a writer? Chilling. It’s easy to become discouraged, to second guess everything you write.

In this age of censorship I mourn the loss of books that will never be written, I mourn the voices that will be silenced -- writers’ voices, teachers’ voices, students’ voices -- and all because of fear. How many have resorted to self-censorship? How many are saying to themselves, “Nope...can’t write about that. Can’t teach that book. Can’t have that book in our collection. Can’t let my student write that editorial in the school paper.”

*

Meanwhile, in the USA, last week the Supreme Court invalidated a part of law that offers special protection for minority voters, and Gary Younge customarily reminded us why we we’re not quite at the promised land of Ebony and Ivory just yet:

For most of the last century, apartheid was not the exception of one nation but the rule for much of the world that described itself as "civilised"...History does not just stop because a memory is inconvenient.

In a related article, he links the narratives that are chosen as good news stories with the Court’s view of racism in the USA.

All mention of what it took to make such a life possible is an inconvenience. The children who were jailed, set upon by dogs and drenched by fire hoses in her home town, so that integration could become a reality, are irrelevant. The people who were killed because they registered to vote, marched against humiliation or just wouldn't shut up when they were told to – so that a black female secretary of state was even plausible, let alone possible – do not fit. Condi made it because she worked hard. Maybe her kindergarten friend, Denise McNair, would have made it too. We'll never know because she was bombed to death by those opposing integration while studying at Sunday school. Segregation was fickle that way.