Internet Histories | 30 June

This week on the internet: how we talk about Google, how we talk about art, and how we talk about voting

This fortnight:

Talking about Google | Talking about art

Talking about not voting

Matt

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="388"] googl plz[/caption]

Almost exactly a year ago, Google launched Project Loon in a remote part of the South Island. The project involves a series of high-altitude balloons that act as relay stations and broadcast towers for the internet, beaming down WiFi signals across huge swathes of land. The trials down south have been ongoing – last week a balloon somehow crashed in North Canterbury. The goal’s laudable-sounding enough: spread cheap or free internet connectivity to people who can’t currently access it – it costs a heap to lay down fibre or copper, and not much at all to shoot out radio waves.

Thing is, Google isn’t doing this out of the kindness of it’s heart. The more people who are on the internet, the more people use it as a platform for searching or sharing, the more data it can collect and the more profitably it can sell you to advertisers. This is obvious and self-evident, but it’s something only rarely mentioned in glowing advertorials about self-driving cars, virtual reality head-up displays and, of course, bringing cheap, fast internet to the world’s poor. The best piece I’ve read recently on Google’s current and near-future business model ran last week in Slate, and I think it’s something most internet users should probably read if they want a very short primer on the tight interrelationship between privacy, information and money:

Consumer data is always the simplest to commodify, though, because unlike Hollywood and record labels and book publishers, consumers don’t have lawyers. As smart watches and smart fitness monitors become tinier and more ubiquitous, as cars get smarter and civic infrastructure gets smarter and your thermostat knows which room you’re in and your clothes know what time you go to sleep and your fridge knows what you ate last night and your toilet knows you’re pregnant, there’s going to be a lot more data, much of it automatically collected, collated, and aggregated… That information is also useful to companies that want to sell you things. And if Google stands between your data and the sellers and controls the pipe, then life is sweet for Google. It’s good to be king—and by “king” I mean “exclusive middleman.”

I’m not saying Google’s bad or evil or somehow below-board. I am saying you should be aware that by using Google’s services, we’re all buying into a system that commoditises our information in a system of hyper-advertising unlike anything that’s ever existed.

Rosabel

Last Thursday, around 100 people gathered in the upper NZI for The Big Conversation, a one-day conference hosted by Creative New Zealand. Pitched at those working in the arts sector, the day's sessions felt like a marketing class if people taking marketing classes actually gave a shit about what they were selling. The titular Big Conversation referred in part to the types of conversations that were taking place between arts organisations and their audiences (mostly dire) and how they could be improved (you can find the reader here).

The day began with a provocation: "We're killing conversation." The cause: "Lazy copywriting." ("Why are dance companies always 'exhilarating',"complained Andrew McIntyre in his keynote, "and why are the dancers always mid-air?") The real highlight of the day, though, was - counterintuitively - a session I missed, but received a full briefing on: Rhana Devonport, the new director of Auckland Art Gallery, on how we talk to audiences about art. If the idea is that art should be accessible to everyone, she posed, then what role does the expert have?

[caption id="attachment_9704" align="aligncenter" width="460"] The director of Tate Britain, Penelope Curtis[/caption]

At one extreme end, the answer is 'none'. Those are the bullets being fired at the Tate Britain, where critics are calling for its director, Penelope Curtis, to be sacked. The controversy here surrounds Curtis's rehang of Tate's permanent collection: she's arranged everything chronologically and removed all explanatory panels. It's a move that's been met with great enthusiasm and unimaginable hostility, and one which brings to the forefront the question of whether there's a 'best' way to experience an exhibition.

There are better ways than Tate. The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart, for example, have nothing on the walls, but gives each visitor an iPod Touch. The device tracks you as you walk around the building, and allows you to access 'artwank' (the stuff that'd usually be on the walls, as well as essays and interviews), 'gonzo' (where founder David Walsh offers his personal take on each piece), 'ideas' (brief quotes and facts that offer point from which to jump) and 'media' (where you can stream video and audio content). You can also rate each piece using a moronic but effective 'love it' / 'hate it' rating system and download your visit when you get home.

The strength of MONA's guide is that it recognises everyone has different preferences for how they engage with art. It's taken me a while, but I've come to realise that what hooks me in most is process, and the underlying desires, fears, and narrative that drive creation.

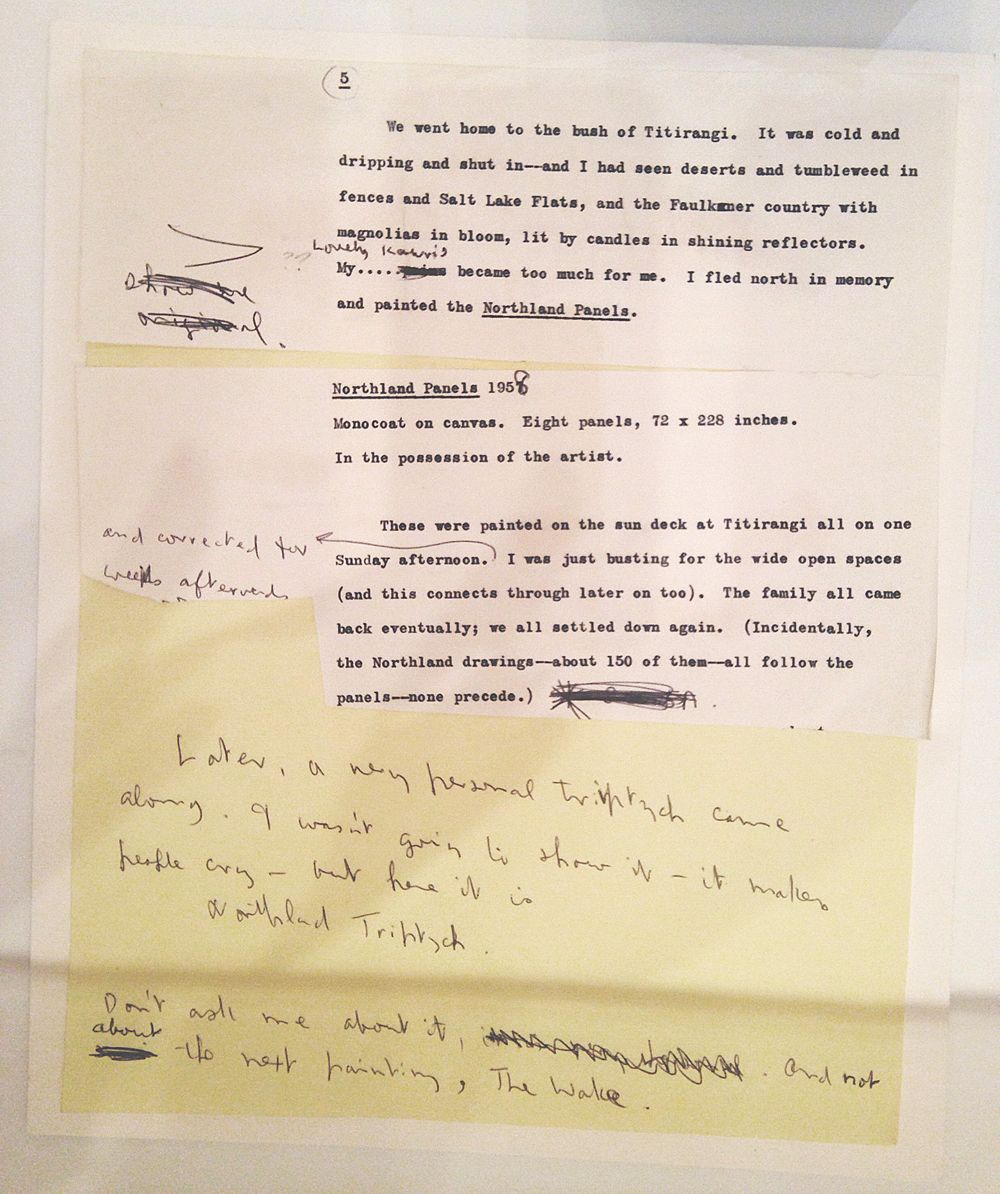

[caption id="attachment_9703" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Excerpt from Colin McCahon's painting notebook[/caption]

Auckland Art Gallery have a small Colin McCahon exhibition at the moment, and sitting in a glass case in the middle of the room is an excerpt from his diary. It tracks the creation of the Northland Panels, which were painted just after he returned from a tour of the States:

We went home to the bush of Titirangi. It was cold and dripping and shut in - and I had seen deserts and tumbleweed in fences and Salt Lake Flats, and the Faulkner country with magnolias in bloom, lit by candles in shining reflectors. My lovely kauris became too much for me. I fled north in memory and painted the Northland Panels.

These were painted on the sun deck at Titirangi all on one Sunday afternoon. I was just busting for the wide open spaces (and this connects through later on too). The family all came back eventually; we all settled down again. (Incidentally, the Northland drawings - about 150 of them - all follows the panels - none precede.)

Later, a very personal triptych came along. I wasn't going to show it - it makes people cry - but here it is:

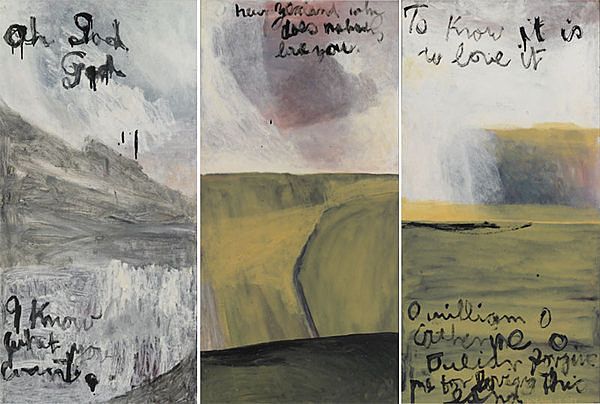

[caption id="attachment_9702" align="aligncenter" width="500"]

Colin McCahon - Northland triptych, 1959 | Inscriptions: (1: Oh God, God / I know what you want | 2: New Zealand why does nobody love you | 3: To know it is to love it / O William O Catherine [illegible] forgive me for loving this land[/caption]

Don't ask me about it, and not about the next painting, The Wake.

Joe

I’m going to be speaking at Auckland’s Q Theatre this evening from 6.30pm at The Wireless’s panel discussion, “Why Vote”? You should come along (you need to click through to register, but it’s otherwise free), but I’m using this morning’s Internet Histories as an aide memoire for what are essentially scratchings, a few stray thoughts as I wrap my head around NZ’s sub-70% and potentially falling voter turnout (heck, enrolment). Consider these spoilers, in the same way that looking at a green screen cyclorama for three hours would constitute a spoiler for the final Hobbit film:

- When this site was in its adorable scattershot Tumblr infancy I wrote a little about voter turnout here and here. The 2001 election had the smallest proportionate turnout of eligible voters since 1887, and it’s still interesting to note that the 1880s were an economically and politically stagnant time where alternating NZ premiers shuffled between austerity and profligate borrowing, and no one actually tinkered with the structure of NZ’s economy or society. From the 2014 side of the bridge, it’s difficult not to look across with a flicker of recognition.

- I made the usual “NZ schools need civics” Internet herb warrior cry at that stage without doing any actual research. Di White’s excellent piece earlier this year broke down some of the myths around it and found that international studies are reasonably glowing about our standard of civics education, and that we punch comfortably above a mean of countries surveyed. This doesn’t mean we’re perfect, but it does mean we’re good. I still think that there’s a curriculum gap between ‘how government works in New Zealand’ and the way we’re taught things like literature, human geography and history in high school (the latter feels like it’s treated like a particularly shameful second-best. Everyone in 7th form, including me, fell over trying to get into Tudor England before that stream closed so that we wouldn’t get stuck doing NZ history. Then I had to do all my internal assessments on NZ history and found out I liked it more. What was the stigma?)

- The International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCES) used a three-tier methodology: the personally responsible citizen, the participatory citizen, and the justice-orientated citizen. If you decide to go and vote this year because it’s an important thing, then congratulations: you clock tier one. But let’s say you do that and expect large swathes of NZ life to change or improve, and let’s say very little does. What I’m getting that is that the youth voting drive, while well-meaning, runs the risk of fetishizing the process of voting in a way that might be short-term successful but shoot itself in the foot down the track. If you have any idea that voting’s worthwhile and you half-heartedly do it when you live at the same address long enough, you might vote a few times in your life. If you’re galvanized like never before to vote this year, and you’re told it’s the most important and wonderful thing, and you do, and nothing happens, you might never bother again. I wouldn’t blame you. We need to equip people with more, because voting on its own is a disappointment.

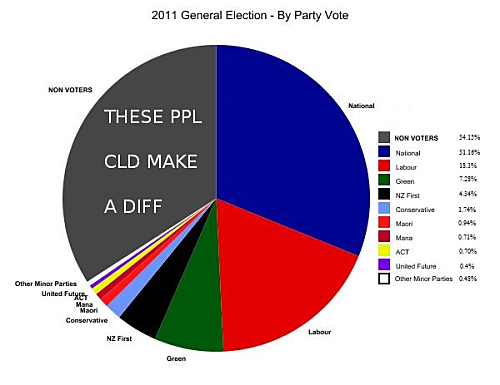

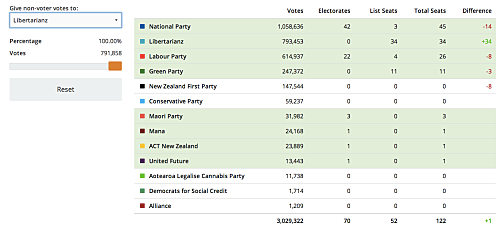

- I’m not going to get too forensic on any graph that contains the label “THESE PPL CLD MAKE A DIFF”, but it’s likely that the author of this ugly guy, currently doing the rounds on Twitter, took the data from MyGov’s excellent Non-voters tool, It demonstrates the heft of the number of people who didn’t vote in 2011’s general election (791,858) by allowing you to allocate as many or as few as you like to the polling party of your choice. This fascinating exercise allows me to show how the slightest variation in turnout and resulting party performance can achieve transformative change that doesn’t take much to believe. Observe:

Elsewhere:

Videos of the Auckland Writers Festival - Eleanor Catton, Alice Walker, A.M. Homes and more

Who Wants to Shoot an Elephant? - Wells Tower for GQ

Why was Teina Pora gagged?

Love me Tinder

The Man who Speaks for Earth

Anti-Vaccination Movement Strikes Out in Bible Belt States

Youth Worker Wages Unconventional Battles for Teen Clients

Rejected Disney Princesses

Bodymore, Murderland

The Supreme Court's Skin-Deep Unanimity

Rock Simulator 2014 trailer (inexplicably NSFW)

Every-day Ukranian Life in 1942 Depicted in Colour Photos

Living the Fitbit Life