Internet Histories | 29 October

The ambiguity of megadeath, list of lists of lists, Hilary Mantel and historical fiction, Illegal Peanut-Factory Sex: urban legend no longer, Jimmy Savile and the cruelty of nostalgia and nanostructural architecture: the interpretative dance

This fortnight:

The ambiguity of megadeath | List of lists of lists | Hilary Mantel |

Illegal Peanut-Factory Sex: urban legend no longer | Jimmy Savile and the cruelty of nostalgia | Nanostructural Architecture: the Interpretative Dance

Matt

There was a space of time, before the Sokal hoax and a million outraged academics, when applying quantum processes to messy human philosophy wasn’t as disreputable as it’s become today. That space is long-since closed up, with an interesting exception I discovered the other day: analogising quantum physics as a type of literary criticism, and applying it to real-world events. I’m speaking specifically of this article, which uses the ideas of superposition and indeterminacy to explore the strange double-think that exists, legally, around the sites of genocides and mass murder.

The mass grave that is supposed to contain the remains of my friend Andrea Wolf is located in the mountains south of Van, Turkey. The gravesite is littered with rags, debris, ammunition cases, and many fragments of human bone. A charred photo roll I found on site may be the only witness to what happened during the battle that took place there in late 1998.

Even though several witnesses have come forward stating that Andrea and some of her fellow fighters in the PKK were extrajudicially executed after having been taken prisoner, there have been no attempts to investigate this suspected war crime, nor to identify the roughly forty people supposedly buried in the mass grave. No official investigation ever took place. No experts went on site.

No authorized observer can break superposition, not because there were no observers, but because they have not been authorized. It is an incompossible place, incompatible with the existing rules of political realism, constructed by the suspension of the rule of law and aerial supremacy, beyond the realm of the speakable, the visible, the possible. On this site, even blatant evidence is far from being evident.

It’s framed in academic parlance, but there’s a moving undercurrent of melancholy that suffuses the piece; though legally it can be hoped an authoritative account of what went on might ‘collapse’ a reputed site of violence’s radical indeterminacy – either missing people were killed here, or they live on, someplace else – realistically we know there’s only one way the wave function crumbles. Steyerl’s forlorn hope that it might be otherwise is by the end painfully clear.

Thematically similarly, this lengthy GQ piece is by a woman who as a teen hitchhiked with murderous, rapist truckers. I don’t know when I became the ‘depressing blogger,’ but hopefully it’s not a forever thing. In the wake of trucker/serial killer Robert Rhoades, she thinks back on a time she saw a woman’s body being discovered in a dumpster behind a truck stop, and decides, years later, to investigate whether he might have been behind that as well.

He wore a cotton button-down with the sleeves rolled neatly up over his biceps and had the cleanest cab I ever saw. He must have seemed okay or I wouldn't have gotten in the truck with him. Once out on the road, though, he changed. He stopped responding to my questions. His bearing shifted. He grew taller in his seat, and his face muscles relaxed into something both arrogant and blank. Then he started talking about the dead girl in the Dumpster and asked me if I'd ever heard of the Laughing Death Society. "We laugh at death," he told me

These girls that disappear – are they dead, killed? Or just off the grid, like she was for all these years? This math’s more in her favour than Steyerl’s, but that’s not saying much. When did GC become such a generally excellent publication, anyway?

The most long-lived people in the world subsist on a small island belonging to Greece. What keeps them alive? I know their secrets, and you may learn them also, here.

Seeking to learn more about the island’s reputation for long-lived residents, I called on Dr. Ilias Leriadis, one of Ikaria’s few physicians, in 2009. On an outdoor patio at his weekend house, he set a table with Kalamata olives, hummus, heavy Ikarian bread and wine. “People stay up late here,” Leriadis said. “We wake up late and always take naps. I don’t even open my office until 11 a.m. because no one comes before then.” He took a sip of his wine. “Have you noticed that no one wears a watch here? No clock is working correctly. When you invite someone to lunch, they might come at 10 a.m. or 6 p.m. We simply don’t care about the clock here.”

Although the concept of a 'society out of time' fills me with vague existential dread, I guess you could get used to it, with the help of 2-4 wines per day.

Wikipedia has a list of lists of lists. Yes.

Yes.

Rosabel

Larissa MacFarquhar's profile of Hilary Mantel in last week's New Yorker is an incredible piece of journalism - authoritative, intimate and with a superb sense of narrative.

She doesn't believe in inventing greatness or significance where none exists. This is why she likes historical fiction: she feels she can write about greatness only in historical moments that have already proved ripe for its flourishing. She believes that there are no great characters without a great time; ordinary times breed ordinary people (of the sort—dull, trapped, despairing—who inhabit modern novels). If Robespierre had lived out his life in Arras, she thinks, he would have ended up like one of her characters in “Every Day Is Mother’s Day”: not enough money, stuck in a bad marriage, frustrated at work, and crushed by self-contempt.

One of the central conversations in the piece surrounds the liberties writers take when working with historical fiction - and if we were to parallel the arbitrary autobiographical fiction-autobiography divide, Mantel would occupy a space closer to history than fiction:

She says, “I cannot describe to you what revulsion it inspires in me when people play around with the facts. If I were to distort something just to make it more convenient or dramatic, I would feel I’d failed as a writer. If you understand what you’re talking about, you should be drawing the drama out of real life, not putting it there, like icing on a cake.”

When she is writing historical fiction, she knows what will happen and can do nothing about it, but she must try to imagine the events as if the outcome were not yet fixed, from the perspective of the characters, who are moving forward in ignorance. This is not just an emotional business of entering the characters’ point of view; it is also a matter of remembering that at every point things could have been different. What she, the author, knows is history, not fate.

So I'm crashing at a mate's and someone has just started having sex in the flat. Thing is, everyone that lives here is in the living room

— Dave Cribb (@davecribb) October 20, 2012

For all the mind-numbing trivialities that flood social media, you do occasionally find yourself privy to some truly entertaining moments. A decade ago, stories like this would have faded into urban legend: a friend of a friend who worked with someone whose peanut-factory flat was broken into to and outrageously co-opted by two complete strangers. Now, we're following the action as it happens, from multiple perspectives, and with accompanying photos and video footage as proof. The whole escapade reminded me of Jennifer Egan's Black Box and new possibilities for how narratives might be delivered.

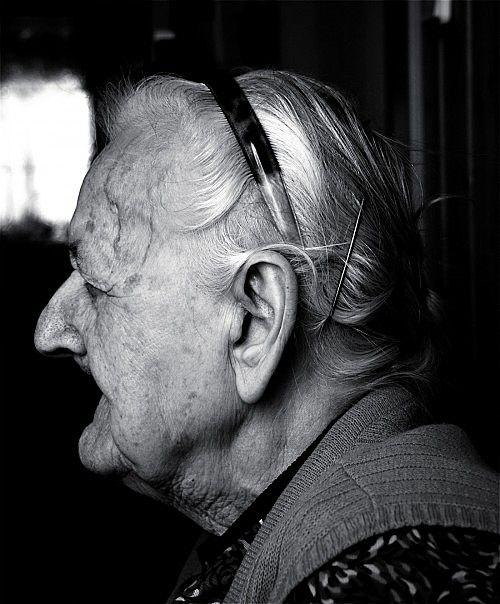

Continuing this trend of documenting every detail of our lives, we're seeing sharing-based sites like Texts from Last Night and My Life is Average evolve into ones like the recently launched He Texted. Alarmingly addictive, it encourages its users to outsource the task of overanalysing messages sent by romantic interests and non-interests alike. Readers vote and comment accordingly, and although your first reaction might be like mine - to cackle with grim disgust and voyeuristic delight - the comments are mostly sincere and often validating (but not worth reading).

Obvious complaints: it's needlessly gendered, and boasts an unfortunate 'Ask a Bro' section, which gives the option of privately messaging a guy who is, for example, "kind of a douchebag, who knows many other douchebags." But mostly it's inoffensive - an artefact of how an age-old tradition is adapting to changing technologies, made particularly fascinating because it chronicles a unique and early anguish. It teeters on the cusp of heartbreak, it's drenched in doomed hope, but it's safe. No matter the outcome, these are small misfortunes in the grander museum of failed relationships.

What boggles me most is that these conversations are being conducted via text.

Joe

I haven’t come across a good longform unbundling of the Jimmy Savile scandal yet – coverage in his native Britain remains too news-cycle hot to stop and walk through the grotesque making and unmaking of a radio and television broadcasting legend. However, the consensus appears to be that one of the worst known sex offenders in British history remained hidden in plain sight within late-20th century pop culture, and public servants and organizations up to the top levels became aware of this and concealed it.

Cressida Leyshon has a good personal response over at the New Yorker, but one that turns to hard scrutiny in the BBC and its part in sustaining the Savile light-entertainment myth:

“…part of the case the BBC makes for itself every time its royal charter comes up for renewal is that it’s the home of quality programming, that it continues to adhere to its mission to inform, educate, and entertain (a mission its Scottish founder, John Reith, took from the American broadcasting pioneer David Sarnoff in the nineteen-twenties). It’s still the place the British public turns to when it celebrates or mourns. The Corporation understands—and exploits—the power of nostalgia, and the way television, in Britain perhaps more than anywhere else in the world, has embedded itself in the popular memory. So the Savile revelations risk tainting forty years of television history, and forty years of shared memories.

And for The Independent, Grace Dent is forceful and angry and right to look beyond Savile to the context in which he thrived. Last fortnight I felt uneasy about Gawker’s ‘gotcha’ on one Reddit troll – that ‘tale of a monster’ narrative, a sort of anti-Great Man theory that exculpates culture. Dent won’t allow her readership to do the same here:

“Over the past few days, I’ve heard people gasp about cover-ups and about upset girls being ignored, peppered with a lot of, “Well why didn’t these women say something sooner?” I think these three things tie neatly together. Instead of faux outrage and arse-covering about history, I’d be happier to hear strident plans to protect and listen to young women in the future, strident plans to stop older men manipulating younger teenage girls, national outrage about sex trafficking of teens in this country now. If you’re 42 with a 17-year-old girlfriend, you’re legally in the clear, but I still find you vaguely revolting.”

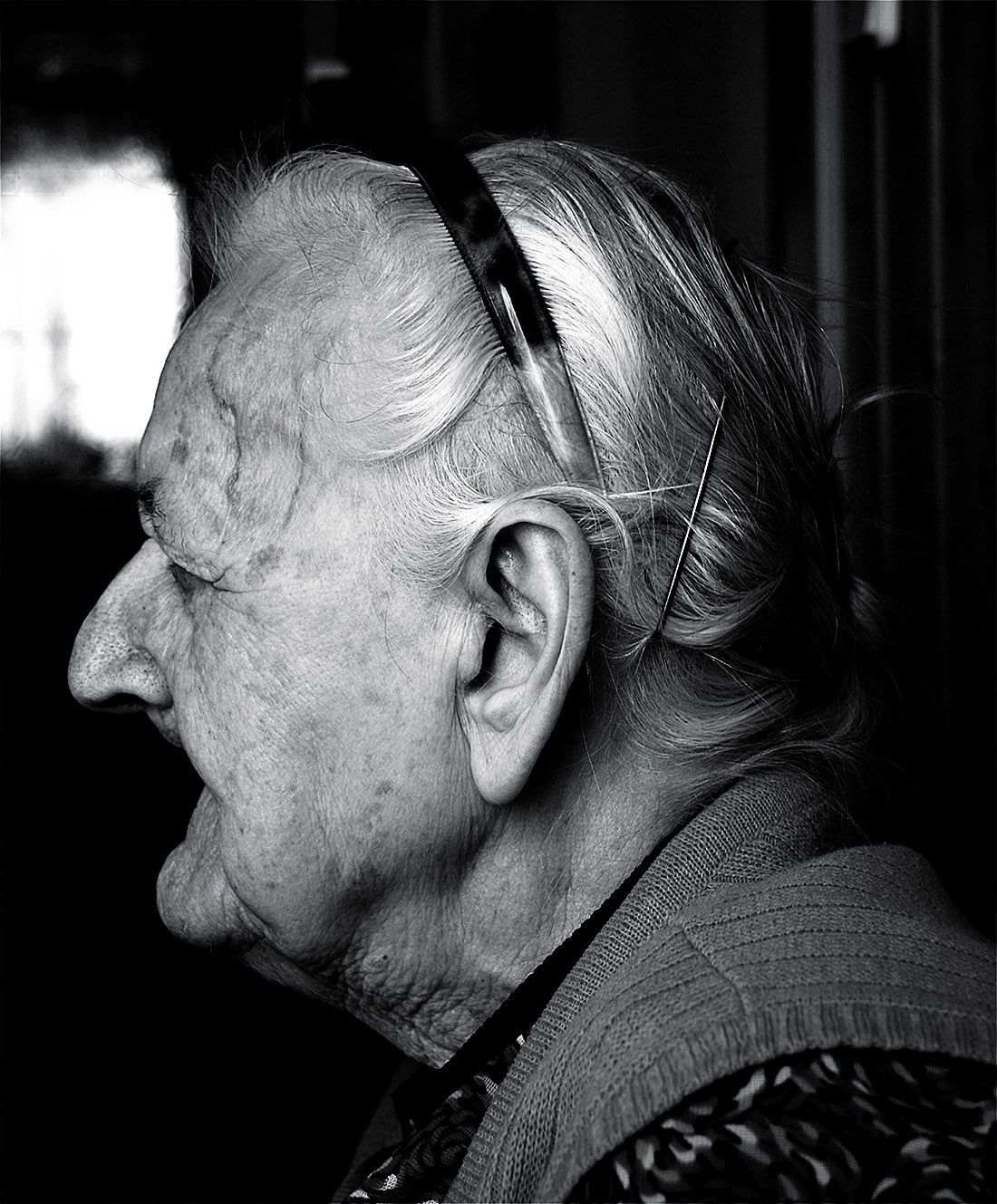

One of the most haunting set of images I’ve ever seen on the Internet (no idea how to find them again, and I’m not up to the grisly challenge of entering the right keywords on Google to do so) was a series of Middle American motel rooms – thick beds, yellowing wallpaper, Gideon bibles, dreary lampshade kitsch – and a spectral hint of movement and activity, like a superstrata flicker of life over the empty scene – an optical double-take. These were photos of horrendous sexual abuse of children – the authorities had come across them, painstakingly Photoshopped the atrocities out, circulated the abandoned, near-identical rooms far and wide – hoping someone could identify them, what city, what highway, what state.

This is what I think about when I imagine the hours of footage of Top Of The Pops and Jim’ll Fix It and Speakeasy, the fodder that became ready-made remembrances on cheap and cheery television retrospectives of the 60s and 70s. In a turn that bears haunting analogy to those motel rooms, tapes recorded on the same reels suggest Savile molested young women as he made his radio show. Executives and producers at the time would have been aware of these recordings.

This recasts cosy nostalgia as something quite horrific – but actually, the whole idea of ‘recasting’ privileges freshly-shocked audiences and trivializes the experience of Savile’s victims for whom it was never nostalgia, who have spent decades inundated by sepia-toned, light-hearted reverence of their abuser. More than ever, nostalgia is churned out in vast and terrible quantities by the victors as a proxy for history – I wonder if in England, this will curb the retromania for a while.

One of my favourite Raymond Pettibon pieces that gets at the same idea, while we’re here:

I had no idea that Science magazine and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences had co-sponsored a ‘Dance Your PhD’ contest for the past five years, but apparently and amazingly it’s for real:

“The competition challenges scientists around the world to explain their research through the most jargon-free medium available: interpretive dance. The 36 Ph.D. dances submitted this year include techniques such as ballet, break dancing, and flaming hula hoops. Those were whittled down to 12 finalists by the past winners of the contest. Those finalists were then scored by a panel of judges that included scientists, educators, and dancers.”

Here’s the winner, Peter Liddicoat of the University of Sydney with ‘Evolution of nanostructural architecture in 7000 series aluminium alloys during strengthening by age-hardening and severe plastic deformation’: