Internet Histories | 29 April

This fortnight - dissecting the Super Mario flop, the commercialisation of Amanda Palmer, applause as a social function, talking about ANZAC day, and the Boston bombings.

This fortnight:

Dissecting the Super Mario flop | Ebert on The Pot |

Manufacturing slacktivist outrage | The economics of Amanda Palmer |

Applause as a social function | The best time to talk about ANZAC day

is ANZAC day | The Boston bombings

Adam

If you haven't seen the Super Mario Bros movie from 1993, it's important to note out of the gate that it's both horrible and visionary, a cynical film made by people hungover from the dark, edgy parts of the 1980s and getting it out of their system in the most visible, unpleasant way. If you have, it probably won't surprise you that it was a troubled production.

In her piece for Grantland, 'Hollywood Archeology: The Super Mario Bros Movie', Karina Longworth positions herself as both biographer and pathologist for the beleaguered film. Her breakdown of the harrowing production period doesn't provide any new material - its value is more in its curation of some key pieces from the time, including a 1992 Los Angeles Times feature that's unflinching in its coverage of the trainwreck backstage and a collection of some of the nine Super Mario Bros scripts drafted (a highlight from the synopsis of one: "The one (misguided) attempt at humor is a scene in which Bruce Willis, in homage to Die Hard, cameos in the air ducts of Koopa’s Tower").

As pathologist, though, Longworth goes right to the source to find the cause of the film's extravagant failure. Longworth buys a NES and a copy of the original game and invites her friends around for some gaming and a movie. Longworth writes with warmth as her friends stick around for hours to take turns with the single NES controller, but once the 1993 movie goes in the DVD player -

...by about 20 minutes into the film the group had collectively done a 180. People started fiddling with their phones. People who didn't smoke went out back to have a smoke. But I had to sit there and watch the whole thing, because for whatever reason I had decided to ask for that job.

Longworth's conclusion about why the film emerged from the Hollywood womb already doomed - it was a "blatant exploitation of a brand name that totally ignore[d] that brand's function and meaning, [a parasite] designed to leech off of warm feelings about past amusements, produced with no understanding of what made people fans of [that brand] to begin with" - resonates today, in a contemporary market saturated with these kinds of films (A Good Day to Die Hard, Total Recall, Transformers 3). And if the failure Longworth identifies is a failure to pander successfully, a failure to adapt to a market , rather than a failure to create a piece of worthy cinema, that's only because the context (one she recognises with a fair degree of bitterness) is one where the Super Mario Bros formula is, twenty years on, actually succeeding; a world where a little extra cash is justification enough for taking stories we love and stripping them of what we remember fondly. Longworth's unspoken suggestion is that, had Super Mario Bros been put through exactly the same process in 2013, maybe it would have had a fighting chance.

Bloomberg Businessweek ran a feature last week about Herman Torres, a young man drawn into a bank robbery scheme by a man on a phone who claimed to be working for the Defense Intelligence Agency. Torres' job was to 'test the security of retail banks' by going into them and robbing them. Armed guards, police or a five-minute wait were cause to flee, as the bank had passed the test. Of course, one robbery did not go according to plan. Of course, Herman got arrested. And of course, all was not as it seemed.

Torres' story is a larger-than-life tale worth reading for the sheer absurdity of what followed Herman's arrest. It's a hoary cliche to say truth is often sometimes stranger than fiction, but Herman's story is one that wouldn't be out of place in a five-dollar paperback in a bin at Whitcoulls - and that's what makes it fascinating.

Roger Ebert died on April 4. Ebert was an incredibly lucid, eloquent writer with an immense passion for the art of film, and his influence is felt in every young upstart reviewer who started a blog or wrote in student media in the last fifteen years. He democratised film criticism, for better and for worse. But, most importantly, he was an incredible advocate for young filmmakers who only had a camera and something to say, as attested to in this video of Roger at the Sundance premiere of Justin Lin's Better Luck Tomorrow.

Buy a rice cooker in his honour. Make something in it. He would've liked that.

Joe

Wellington's Saziah Bashir is finally blogging under the nom de plume "Brownie Prolix". She wrote the following heartfelt and deeply resonant piece about why MP Richard Prosser's Investigate column about profiling young Muslim men was so vile - whereas most responses were a white Herald harrumph of propriety or just hashtag satire, she actually made the case for why it mattered. For her inaugural post on her own space, she's taken a very hard look at the "pls like-pls share-1 click means 1 dollar" ethos of Facebook - often initiated by companies, usually propagated by the well-meaning, accomplishing precious little. If this is familar territory, her particular critique isn't - members of the young Bangladeshi diaspora sharing pictures of partially-crushed people in vibrant and unsubstantiated appeal, whose engagement with homeland politics are limited to the odd parental rant, who oscillate between apathy and the odd flurry of outrage when something kills enough people:

I disagree that a picture is always worth a thousand words. Even a thousand words is sometimes not worth a thousand words. If you feel strongly enough about something, take the time to engage. It needn’t be lengthy prose. But this two second share and retweet exercise of something fraught with problems which you then discard in your mind a second later means nothing. In fact, it’s harmful.

I don’t know how we participate meaningfully. But I know how we don’t. We don’t make it a trivial one click experience. We don’t dwell in the grotesque and trade in shock value at the expense of respect and engagement because it’s easier and garners a bigger, quicker response. We don’t exclude. We don’t harbour the grand and ultimately self-serving delusion that we can “save” anyone (because too often I’ve heard educated Bangalis talk of “teaching” the “lower classes” in language borrowed directly from the colonizers who once sought to tame us savages).

Sure, Bashir allows, some of us talk about issues and solutions and share practical on-the-ground information, but there's a lot of noise that we consciously choose to make. Obama's Digital Director, Teddy Goff, visited New Zealand in February. One of his social media 'takeaways' (ugh) was about what people share - and no surprise that it tends to be the stuff that makes us look, at least superficially, like well-rounded and interesting people (ie: no one wants to be the guy who's on Facebook admitting they read about the Kardashians).

We'll form an echo chamber for marriage equality once it's legislatively a done deal, for protecting dolphins and kittens after an environmental disaster, for huge, sad-eyed children after a building collapse or a famine. Information that lacks a face or is systemic doesn't let us offer up a concerned and 'switched-on' facet to the world quite so easily, because the world is in a hurry - too bad, because it's this kind of information that can have real preventative application if shared and learnt.

This isn't some declaration that we need to start posting reams of text online - because if it's designed and presented well, you can convey important information on an infographic too. But Bashir is right that even those of us who are stuck on Facebook have choices about how we use it, just as much as we have choice about what we say aloud. Let's pad out the water-cooler conversation with some substance.

If you haven't read a Thomas Friedman column before in the New York Times, save your free monthly quota and continuously hit F5 on the Thomas Friedman OpEd Generator - a genius bot that produces a near-perfect simulation of his proto-TED Talk slashfic. Every point on your Friedman checklist is here. Travel anecdote as key to generalised truth? Yes! The knowledge economy as experienced by sage foreign taxi drivers? Yes! Homily upon homily about a globalising (or, 'flattening' world)? Yes!

Let's make America for the world what Cape Canaveral was to America: the world's greatest launching pad. If I had fifteen minutes to pitch my idea to politicians, I'd tell them two things about gas prices. First, there's no way around the issue unless we're prepared to spend more: and not just spend more, but spend smarter by investing in the kind of human capital that makes countries succeed. That's going to require some tax increases as well, but as they say, "them's the breaks."

Second, I'd tell them to look at Norway, which all but solved its gas prices crisis over the past decade. When I visited Norway in 2001, Tintin, the cabbie who drove me from the airport, couldn't stop telling me about how he had to take a second job because of the high cost of gas prices. I caught up with Tintin in Oslo last year. Thanks to Norway's reformed approach toward gas prices, Tintin has enough money in his pocket to finally be able to afford a soccer ball for his kids.

It's good to see the talks between the president and congress getting off to a solid start, but we know there will be plenty of partisan fireworks before any deal is cut. If I had fifteen minutes to pitch my idea to politicians, I'd tell them two things about capital gains. First, there's no way around the issue unless we're prepared to spend less: and not just spend less, but spend smarter by investing in the kind of green energy that makes countries succeed. That's going to require some tax cuts as well, but as they say, "Ya gotta get down to brass tacks."

I don't know what Luxembourg will be like a few years from now, but I do know that it will probably look very different from the country we see now, even if it remains true to its basic cultural heritage. I know this because, through all the disorder, the people still haven't lost sight of their dreams.

On the other hand, there's not much to be said about Amanda Palmer's TED talk, but it helps to tease out some of the stuff that's a matter of taste (her music's drippy theatrical excess, the frustrating and obscuring distance of its melodrama, the way 'punk cabaret' seems more like borrowed nostalgia for edgy high-school virtuosos and less like a bid to shatter taboos - okay, you see where my taste lies) from a series of words and deeds that suggest a complete failure to come to terms with privilege, class, and a basic economic history of the music industry. Writing for NY Mag, Nitsuh Abebe does a good and considered job of it:

She’s politely explained and defended her choices at length on her blog, but the forum Palmer chose to unpack her philosophy as a whole turned out to be both the most ideologically friendly and the easiest to mock: She recently gave a TED talk. As TED talks go, it hit all of the right marks. She wrapped the length of her career, from street performer to lecturer, around the kind of single, simple insight that appeals to people who regularly consume fairy tales about creatively “disrupting” established business models and summoning Utopia via Wi-Fi.

I have sympathy for this argument, because the exchange she's talking about really does get lost when we talk about the economics of art; we focus on material questions of who should pay for what, and often act as though the attention and approval artists get from us is a bigger gift than the world full of art we get from them. However: Palmer’s logic here is itself generally identical to cold, hard free-market capitalism. Yes, the exchange she’s describing is “fair” — everyone involved is willing and happy to engage in it. It’s also “fair” to pay someone minimum wage for work that makes you millions, and fair for a male musician to spend every night having sex with starstruck, consenting young fans, but fairness is not the same thing as nobility, and neither of those arrangements is something you’d present as a revolutionary new relationship.

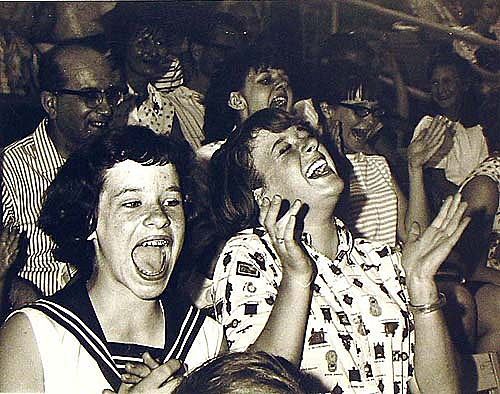

His conclusion is on it too: love her or despise her, Palmer's Kickstarter and app-fuelled public persona now faces the same gap as any commercial entity that reaches out to an online audience: some people are going to want what you're selling, while a whole lot are going to be infuriated when they incidentally encounter it. The question of whether this is simply the myth of 'the divisive performer' writ large or the cold-hard reality of persona as product may be a vexed one - but Palmer sure as hell isn't the first, or the funniest to cross it:

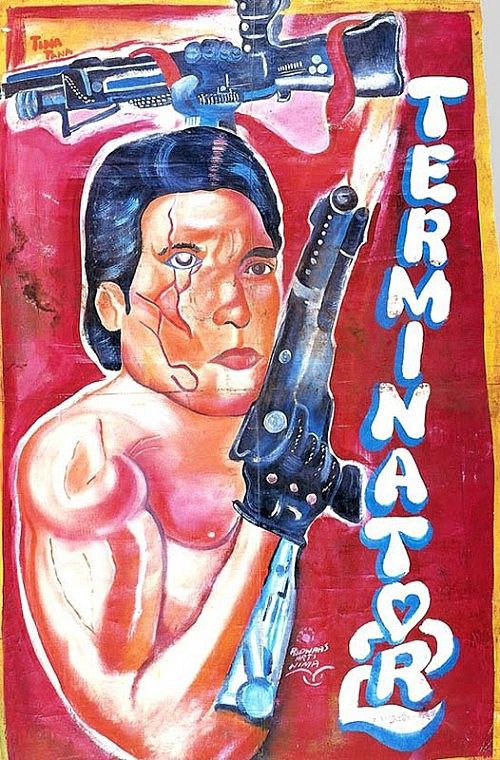

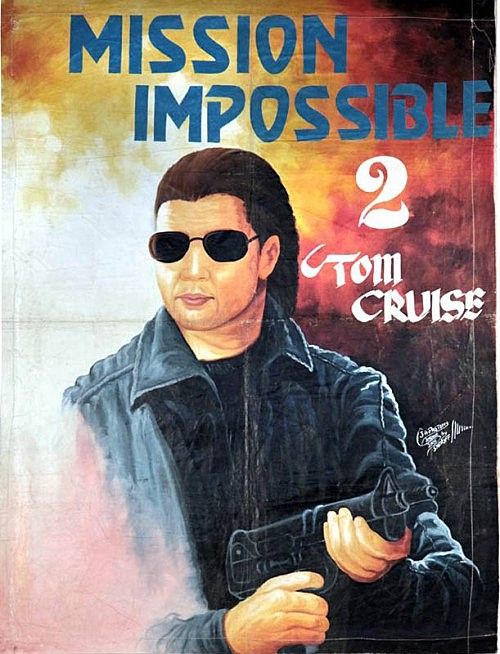

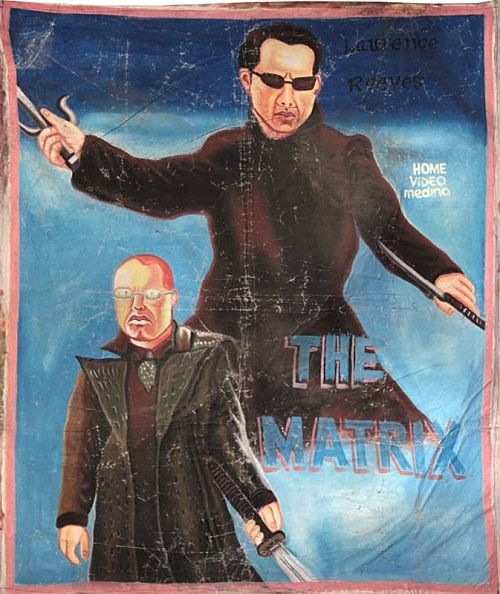

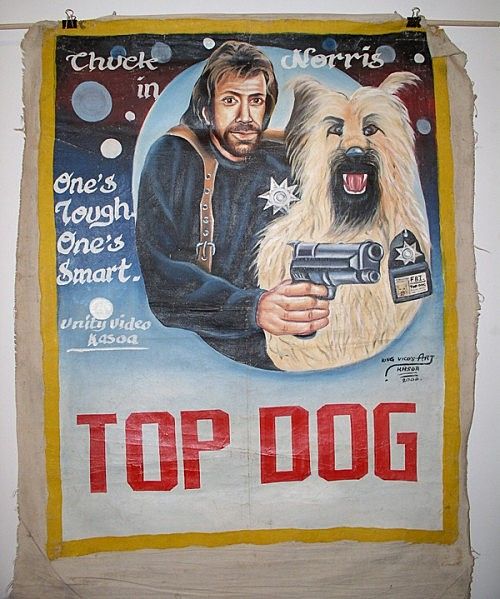

Finally, these oil-on-canvas film posters from Ghana's fledging film theatre industry are lurid, crude and quite wonderful. The story goes that, with the arrival of videotape and VCR equipment in the 1980s, rural audiences were able to see international films for the first time, and a roaring trade of mobile cinema travelled from town to town with social club or open-air engagements. Screenings were presaged with locally commissioned and painted posters for the likes of Terminator, Face/Off and Mission-Impossible.

More can be seen here.

Bronwyn

I was going to link some articles I've been reading about comedy, and why it's so often the preserve of a particular group of people (like the comedian I saw as part of a group show last night who made a joke about how gross it is to have sex with their pregnant wife, because the penis might touch the baby, hahaha/ewwww/hahaha! and his wife was so horny she raped him, big laugh!) but as you could imagine, it's all mostly pretty dispiriting. However, as a worthwhile diversion I did find this list from Amy Poelher on the habits of her co-star Adam Scott.

On a related tack, The Atlantic has a history of applause, including the theory that the Alexandrians had three categories of applause, so admired by Nero that "he selected some young men of the order of equites and more than five thousand sturdy young plebeians, to be divided into groups and learn the Alexandrian styles of applause ... and to ply them vigorously whenever he sang."

Even the modern audience member can be struck by the differences in how audiences use applause; on Broadway the convention is that actors are clapped on entry, to the point where this regularly threatens to derail the whole production, and directors are tasked with coming up with increasingly inventive ways to circumvent this.

The writer makes a slightly tenuous link made between clapping and the use of Like buttons and retweets; yes, both are ways that people give approval of a person or idea, but this ignores the fact that applause from a crowd is almost exactly the opposite of an individual sitting alone pressing a button; also, our conventions of performance and being an audience member mean that clapping is so codified that often we don't even know why we're clapping.

Finally, I'd like to suggest that the best applauder in NZ is the composer John Psathas, who engages his whole upper body to create a resonant and enthusiastic clap. The "Elegant Woman" would be appalled.

Jose

I missed Gordon Campbell's column on Friday, but I'm glad I caught up eventually because he wrote about the previous day's ANZAC events.

The point is that the official tone of the day’s events is almost uniformly celebratory – which is arguably not the best or only way of honouring those who died, or those who came home wounded in various ways. In the process the allegedly glorious nature of the human sacrifice involved tends to drown out the consideration of the horrors of war, and the craven nature of many of the decisions that generated them.

While I don't think it's quite right to describe ANZAC day 'celebratory,' it could be twice as wrong to call it exploratory.

I once contacted a prominent comedian to ask if he would take part in a fundraiser I was organising for the journalist Jon Stephenson. He declined, citing Metro's decision to run Eyes Wide Shut (Jon's expose on how New Zealand soldiers in Afghanistan broke the Geneva Conventions by releasing prisoners over to US and Afghan forces knowing it was likely they'd be mistreated and, possibly, tortured). He said he couldn't respect the fact that the issue of Metro with Jon's story was published during ANZAC week (I think it might have even gone out on the 25th), that he was "pro-SAS" and "although he is not accusing them of torture I personally think prisoners do need to be transferred to Afghan authorities as it is their country and is not our job to try them."

Putting aside the fact he clearly hadn't read the article (Jon's sources include SAS members) I appreciated the fact he took the time to politely point out his objections. I appreciated how it illustrated a particular view: anyone pushing out media critical of the military during ANZAC week must be doing it for extra publicity and that is disrespectful.

The positioning for media exposure is a given and I don't think it necessarily follows that it's disrespectful. Done the right way, ANZAC day, or at least that week, is a perfect time to examine New Zealand's military adventures overseas. Take, for example, He Toki Huna, Annie Goldson and Kay Ellmers' understated but strong documentary on the war in Afghanistan seen through the eyes of Jon Stephenson. The full doco is online and an extended version is, apparently, to be screened during the film festival this year.

Matt

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] A part of Boston's skyline from the top of Bunker Hill[/caption]

I woke up a few mornings ago and habitually checked my phone see what the world had been doing while I slept. An email received in the early hours caught my eye – it was from a close friend, just one line long: Don’t worry – was not near explosions.

I immediately started worrying.

At the beginning of 2012 I spent some time in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a stroll over the Charles from Boston’s CBD. After a month confined in an RV, rushing between cities, two weeks unhurriedly wandering Boston was good for the soul, even in the dead of winter.

Boston’s not like any other town in the States. Cosmopolitan and massive, it revels in its history, with stories of heroes and sites of tragedy linked not only by historical walking trail, but also through a foundational mythology. The city’s heart beats less frenetically than mad New York, and its people are more willing to stop and smile and say “excuse me.” They slowed rather than accelerated as you crossed the street. It felt almost homey; I loved the place.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] This giant flag hangs from inside the JFK presidential library. In Dallas last week, Obama spoke briefly of the bombings while opening the George W. Bush presidential library.[/caption]

I found myself trying to ignore the grisly details, but it was impossible – endlessly iterated via social media, they were hard to hear, but harder not to. Pressure cookers and baseball caps and tourniquets and backpacks and nails. Then, days later, a shooting at MIT - where two friends and a dozen acquaintances study - and then a night spent listening to the police scanner and refreshing twitter as a manhunt sent a city into “lockdown.” What is lockdown? Is it like martial law?

More details: a boat, a tarp, an infrared camera and a gunshot to the throat. They were white, but also ostensibly Islamic, and everyone knew what that meant. The boy caught alive was not read his Miranda rights.

Throughout, a deluge of ‘news.’ Reporters stood on Boston street corners, gleefully solemn, and hysterically spoke nothing. People were accused of being involved, and then accusations were revoked in light of better CCTV angles, a measure of how far we’ve come since Salem (just a short drive up the road). It was a chaotic mess, and now the suspects have been either charged or killed, and it remains a chaotic, fucked up mess.

Some supporters are already rallying behind the surviving suspect, suggesting the brothers were victims of a ‘false flag’ operation perpetrated by the US government. I followed a link on Facebook to one such conspiracy theory website. It had detailed diagrams and asked pointed rhetorical questions and showed a photo of the older brother, naked and dead on a table, with dark wounds gaping and deep holes excavated from his body – it made me sick.

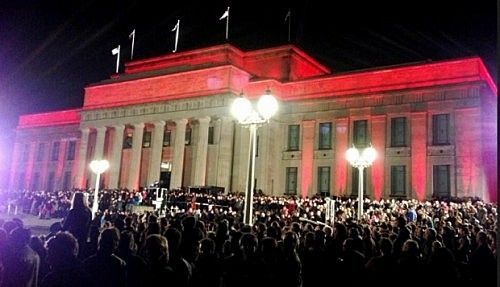

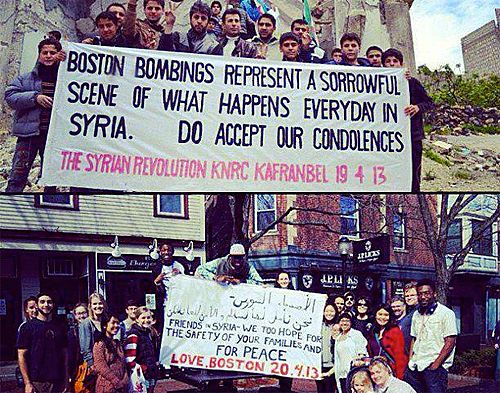

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] Noticing a trend here[/caption]

The internet abounds with more mainstream analyses of the Boston events. The most unexpectedly muddled comes from The Atlantic:

“But perhaps less important than whatever their rationale turns out to have been is how the United States is reacting to the events of this week. On that score, the initial reactions here suggest that we may have turned a post-9/11 corner, still shocked, still pained, but no longer so fearful, so ready to blame religious zealots, and so willing to discard the freedoms that give us such strengths and yet can, at times, leave us so vulnerable.”

This is very perplexing. An entire city sequestered as shops didn’t open and people were told to stay inside during the manhunt. Several people had their faces inappropriately plastered on national newspapers and magazines as editors around the country raced to finger someone, anyone, for the explosions (what was that about Salem?). People began openly praising the CCTV cameras that recorded much of the marathon crowd, and the concept of a surveillance state was spoken about, for the first time in my recollection, with a sort of aspirational fetishization. None of these steps actually contributed to capturing the suspects, who outed themselves by mysteriously shooting an MIT cop, then getting chased down the old fashioned way; the younger brother wasn’t located until people were ‘let’ back onto the streets, and someone found him cowering in a boat.

This article in Salon – “In Boston, our bloated surveillance state didn’t work” – clarifies my objection, and unlike the one from The Atlantic is worth a read.

There’s also the misplaced impulse a certain sector of the political spectrum seems to entertain when tragedies like this strike American targets, to equivocate on the root causes global suffering – as if there’s a quota on caring, and it’s all used up mourning Pakistani children murdered by drones. It was especially foul after 9/11, but social media’s expanded public sphere means that odds are, some of your friends posted something a bit off-colour, as some of mine did.

Even so, there was a kind of silver cloud to the bombings – if you can call the expanded venn overlap of ‘civilians’ and ‘people who have endured bombings’ a silver lining. Kafranbel, a small town in Syria, expressed their sympathies to the Boston victims, and Boston responded in kind. It’d be nice if signs like the above didn’t have to exist, but in the meantime I’m just glad they do; despite the 70,000 people so far killed in Syria’s ongoing civil war, it means that at least some participants in that ongoing tragedy haven’t used up their stores of empathy just yet.