Internet Histories | 25 November

This week: selfies, seeking asylum and interviewing Manson, then and now.

This Fortnight:

Selfies | Seeking asylum|

Interviewing Manson, then and now

Maddie

None of us should be listening to anything Jezebel says anymore, and largely we don't. Occasionally, though, Jezebel posts something so wildly off-the-mark that we all end up talking about it, like last week’s anti-selfie piece. The author’s argument is that the selfie phenomenon shows a narcissistic preoccupation with beauty, particularly within young girls; and if that sounds like old news to you, that's because it is. It's the Original View of selfies, a view which was being gradually shifted by a number of pro-selfie defences which argued that these pictures can be social, empowering and feminist; Jezebel's piece is therefore backlash-thrice-removed, which leaves us basically back at square one. The internet's response was rapid and largely unimpressed, spawning the hashtag #feministselfie and an uprising of pro-selfie support.

A few quick thoughts: firstly, selfies really don’t take that much time to shoot, and the idea that young girls are passing their time by taking selfies instead of getting diplomas is manifest nonsense. Secondly, selfies are not always an exercise in "look at how beautiful I am"; sometimes people — including male people! — post ugly selfies, sad selfies, staunch selfies and silly selfies. Thirdly, there is actually nothing wrong with the classic “look at how beautiful I am” selfie; in fact, in a society that exhorts women to hate the way that they look, there’s actually a lot right with them. Finally, and relatedly, “look at how beautiful I am” is not the same idea as “look at how well I comply with conventional beauty standards”. The best thing about selfies is that they allow people (particularly female people) who are not traditionally seen by the media to put their images in our faces anyway, and that’s radical, and beautiful, and feminist.

Matt

Australia’s recent elections were divisive and nasty in many ways, but both major parties were in remarkable agreement on one particular issue: boat people. Refugees, asylum seekers, queue jumpers – these desperate people are portrayed by politicians and media as a pestilential, invasive force of almost existential proportion. It's a lie, of course; Australia’s population and geography and economy are all vast enough to soak up every would-be migrant without issue, but somehow it has become electorally inconvenient to point this out.

The biggest problem is that when asylum seekers are a dark cloud over Australia's northern border, they are no longer human. Whatever hopes or fears they might have are elided away until at best you're left with nationalities: Afghanis, Iranians, Pakistanis, Georgians.

A recent piece in the NY Times goes a way to redressing the dehumanising rhetoric. Two westerners, a reporter and a photographer based in Kabul, attempt to make the same journey thousands of others from that city have made, pinning their hopes on the Lucky Country. Along their way, they meet individuals and families stuck in a nightmarish transitory limbo; impoverished and bored in Jakarta apartment blocks, terrified and seasick on the open water, and with haunting photographs chronicling everything, it’s simply one of 2013’s most important pieces of long-form journalism.

The elections were scheduled to be held less than a week after the night I found Youssef and Rashid drinking in the courtyard. Whichever candidate prevailed, one thing was certain: neither Youssef nor Rashid, nor Anoush nor Shahla, were going to get to the place they believed they were going. Rashid would never be reunited with his wife and sons in some quaint Australian suburb; Youssef would never see his children “get a position” there; Anoush would never become an Australian policeman; Shahla would never benefit from a secular, Western education. What they had to look forward to instead — after the perilous voyage, and after months, maybe years, locked up in an isolated detention center — was resettlement on the barren carcass of a defunct strip mine, more than 70 percent of which is uninhabitable (Nauru), or resettlement on a destitute and crime-ridden island nation known for its high rates of murder and sexual violence (Papua New Guinea).

Joe

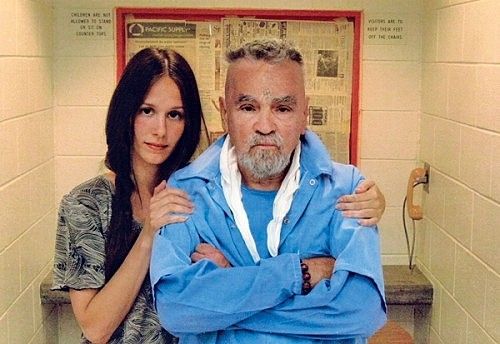

Rolling Stone’s 4-star reviews of the Black Keys and the Killers are like Playboy’s centrefolds. Discerning loyalists will tell you this is just what sells copies, but they’re really reading for the articles. I’m prepared to accept this is a big deal to Rolling Stone still, though: Rick Perlstein’s been brought into their fold to write about politics and history, the late Michael Hastings won them the George Polk Award in 2010. And the next print issue features Erik Hedegaard interviewing a 79-year-old Charles Manson, a piece of work apparently two years in the making.

So far, so good. Until you read the thing, then compound their mistake by going, as invited, to read their original coverage of Manson and his followers. David Felton and David Dalton filled 22 pages of the June 25, 1970 issue with a special report. Waiting for his trial, stymied at every corner in his efforts to appear as his own attorney, Manson sought out the attention of Rolling Stone partly because he didn’t trust the L.A Establishment press, and primarily because he still saw himself as an ascending rock star.

By the time Felton and Dalton got to see him, he was only being allowed one monitored phone call a day (if he dialed a wrong number, it counted). Their exclusive could have just been a recital of his paranoid fugues. Instead, it’s labyrinthine, taking in the way his family’s crimes unfolded, the press ethics, the kneejerk reactions – the excesses of the right and the kneejerk embarrassment of the left. The odd characters that were drawn into his web and spat back out. The burnt-out followers, left behind on an empty ranch at the end of the world. At the start, they describe Los Angeles’ shape as resembling “some discarded prehistoric prototype for a central nervous system” – huge, unknowable, but with some closely-guarded internal logic. And it’s not a bad analogy for the way the 1970 pieces changes perspectives, time, and setting. You will need to set an afternoon aside.

It gets what Hedegaard’s piece doesn’t – that Manson isn’t as interesting divested from his associates and from his cultural ramifications. We get a lot about Hedegaard’s interactions with Manson in prison, what it feels like when he touches you. We even get to hear about how annoying it is when Charles Manson interrupts you with a phone call when you’re trying to enjoy The Big Bang Theory. But his new young love interest, the old adversaries that put him away and then made their millions off gruesome true crime books, his sustained and fanatical Internet fandom – these all feel like distant cyphers.

There are a couple of highlights, courtesy of Manson’s foul but unfiltered screeds, but it’s hard to understand how a slightly eerie encounter with a very famous old prisoner who is definitely mentally ill took two years of work, when Felton and Dalton can’t have had more than six months. If anything, it feels like a failure of nerve (and, in fairness, economics) - we should be doing more Felton/Dalton mindblowers on the present, and not on spooky relics.