Internet Histories | 15 October

The unmasking of the biggest troll on the web, the ministry of social development's shoddy security, tesla coil, open-source academia and how to spot a feminist

This fortnight:

On the Unmasking of the Biggest Troll on the Web | The Ministry of Social Development's Shoddy Security | Tesla Coil | Open-source Academia | How to Spot a Feminist

Joe

I can’t really recall a time when I’ve used it, but I suppose Reddit is one of the few websites that essentially functions as a macrocosm of the whole Internet itself. Its surface is a crowd-sourced mish-mash of trivia, celebrity, broad humour and occasionally actual news, its 100,000 ‘subreddits' appear to run the gamut of every possible hobby, interest and urge, and its depths are a source of all kinds of unholy terror – hate speech, cruelty and underage photos.

It’s also functioned as a sort of sealed-off concha bullosa to the rest of the Net. It plays by its own rules and its own lingo, forged by a well-delineated hierarchy of users. It protects its own – they meet each other in real life, see the faces behind the personas, then respectfully return to their double lives. Now, Adrian Chen’s Gawker piece ‘Unmasking Reddit’s Violentacrez, The Biggest Troll on the Web’ has well and truly shattered those barriers, causing Reddit to go into lockdown and ban outbound links to the NYC blog.

Chen delves into what are inarguably the site’s nastiest and most maladjusted corners – ‘Creepshots’, aggregating photos of women taken without their consent; ‘Jailbait’, where photos of 13-year-old girls in bathing suits were traded on the most marginal of terms; ‘Chokeabitch’; ‘Misogyny’; ‘Incest’. The list goes on. Most crucially for the piece, Chen also claimed a scalp: 49-year old Michael Brutsch of Texas, who under the moniker ‘Violentacrez’ instigated then moderated some of Reddit’s most repellent substrata. As the Guardian’s Jemima Kiss notes, “Under Reddit's guidelines, publishing sexually suggestive covert pictures of women would be acceptable, but identifying Violentacrez by name would not be”. Chen burst the bubble – this is his real coup in terms of sheer tenacity, though I question whether it’s a real coup for journalism.

Questions I have reading Chen’s piece, and it is compulsively readable because we’ve all seen vitriolic abuse on the Internet, always wondered about who jabs on the poison keyboard on the other side of that screen; why is a story that’s on one level about a private company’s uncomfortably laissez-faire attitude to freedom of speech’s shuddering fringes also about unmasking and ruining one individual? If an entire culture has formed around rape fantasies, bestiality and god knows what else, why focus on Brutsch with so much ‘Public Enemy #1’ hype? Is Gawker suitably confident that its ethos, from its selection of stories to its comments section, lets it leave the glasshouse and cast stones?

And having learnt from Chen that the real Brutsch is meek, overweight, weak-chinned, goes home to a disabled wife and a mortgage, how are we meant to feel about this passage -

He asked a number of times if there was anything he could do to keep me from outing him. He offered to act as a mole for me, to be my "sockpuppet" on Reddit. "I'm like the spy who's found out," he said. "I'll do anything. If you want me to stop posting, delete whatever I posted, whatever. I am at your mercy because I really can't think of anything worse that could possibly happen. It's not like I do anything illegal."

- knowing that Brutsch is outed, has been outed, will presumably lose his job?

Chen rightly refutes Reddit logic – the pernicious and reality-skewing idea that outing Violentacrez is worse than distributing ‘creepshots’ of real, unsuspecting and innocent women – but does that amount to a justification for outing Brutsch the way he does? One argument might be that personalizing the story, by leading front-and-center with a human face as part of a broader critique of the culture Reddit fosters, means more people are likely to end up seeing it. I still find myself reckoning with whether the ends justify the means here.

Though I’ll keep following the US presidential race on the most superficial of levels (watching the debates; posting hilarious pictures of Paul Ryan working out on my Facebook) I’m tapping out of all the meta-punditry, the articles about articles about polls and strategy, the parallel universe of US politics as an elaborate lattice of elite movements that weirdly, horribly, starts to affect the decision-making of actual leaders.

Then I’ll return to this David Grann New Yorker piece from 2004 as a salve. 'Annals of Politics: Inside Dope’ is another enviously subtle and observant piece of writing – starting with a slack-jawed bemusement at the world of political news digest editor Mark Halperin (the jargon, the news cycles, the trivia, the jargon, the positioning, the jargon) Grann quietly, slowly reveals more background – the story of Halperin’s dad, the story of how we got here, and artfully wraps it all together with a question to Halperin that reveals how trapped he is, how much poorer we may be in the 21st century as a news audience:

Just imagine Deep Throat during the current age. On cable TV every day there’d be guessing games on who it was. Bob Woodward would be staked out, and there would be profiles and journalistic stories about the journalism and was it ethical and how many sources did they have. You’d have a countdown clock on some cable channel of when Nixon’s going to resign. You’d have Web sites with endless speculation about who Deep Throat was, and critiques of the language, and textual analysis of every Woodward and Bernstein story. All of that would serve to dilute and diminish not just the exclusivity of the scoop but the importance of the underlying story.

It makes you want to close all the news-related tabs on your browser for a little while.

Keith Ng has dropped one of the scoops of the week by revealing just how easy it is to foist your eyes on the personal details of Ministry of Social Development clients - including the most at-risk kids in the Child Youth and Family Service’s books, bills from pharmacies to CYFS facilities revealing what drugs their young charges are being prescribed, and the name and details of at least one individual’s suicide attempt.

How did Keith do this? Terrifyingly simple: he walked in off the street in some shabby jeans and logged in to one of Work and Income’s self-service kiosks. This belies the huge amount of time and effort that went into poring through what he found, though (not to mention the possible legal liability in being the one who accesses that information, effectively ‘taking one for the team’ on a fuck-up that may have otherwise gone abused but not reported). This is an astonishing act of investigative journalism – please consider donating on his page.

Finally, I loved LEGO as a child, but this Dutch 14-year-old puts me to shame while reminding me how fun it was.

Matt

Andrew W. K. plays loud, fast, ridiculous music. ‘Electrifying’ is a word often used to describe his live shows, but that became literally true last Monday, when he played a keyboard hooked up to seven tesla coils and spent thirty minutes electrocuting David Blaine, street magician.

Blaine is actually perfectly safe – he’s wearing a faraday cage, a metal mesh that directs the electricity away from his body, but the actual danger comes from his standing on a tiny raised pedestal for 72 hours. That is, despite being constantly zapped by (apparently) a million volts, Blaine’s true enemy is a stray gust of wind. Also it rained.

We were soaking wet, singing along with some of the stupidest lyrics ever conceived, while a man on a pedestal was electrocuted, repeatedly.

More here.

The 22 year old Marina Keegan was the president of the Yale College Democrats student association, she was a playwright, and she was a ferociously intelligent writer and organiser. Despite her youth she had recently been accepted into an editorial role on the staff of the New Yorker, when, in May, she died in a car crash. It’s horrifying that a person with so much promise could be so casually snuffed out, but the publication where she was to work recently published a short story of hers – as a kind of tribute, I guess. The story deals with a young woman of Keegan’s age dealing with the sudden death of her boyfriend.

“They weren’t dating,” Sarah whispered to Sam, and I gave a soft smile so they knew it was O.K. that I’d heard.

But it became clear very quickly that I’d underestimated how much I liked him. Not him, perhaps, but the fact that I had someone on the other end of an invisible line. Someone to update and get updates from, to inform of a comic discovery, to imagine while dancing in a lonely basement, and to return to, finally, when the music stopped. Brian’s death was the clearest and most horrifying example of my terrific obsession with the unattainable. Alive, his biggest flaw was most likely that he liked me. Dead, his perfections were clearer.

It’s probably the best and most melancholy thing I’ve read all week.

Last week I attended a talk by Sir Richard Friend, a visiting physicist from Cambridge. His work involves using organic chemistry to facilitate novel new technologies – foldable plastic solar cells, rollable colour epaper, printable touchscreen newspapers — that sort of thing. Though he primarily talked about his research, he segued several times into mentioning the commercial side of academia: patents, papers, and spin-off companies.

A company he helped start that sells photovoltaics, Eight19, was named for the amount of time it takes light from the sun to reach earth, but one supposes it might double as an aspirational share price for a hypothetical IPO.

Dr. Friend (he was indeed amiable) spoke of patenting the invention of the LED in the early 90s, and how at the time it was a rare move, highly disapproved of, but how it’s become far more common and acceptable. Why do publicly-funded universities — like Cambridge — conduct research? Is it to deepen the pool of human knowledge? If that’s true, why are research papers so expensive to gain access to? A single peer-reviewed paper, 20-30 pages long, might set an individual back $50 or more, and the cost to university libraries is staggering.

Indeed, the process of research publishing is highly curious, and very profitable in exactly one direction. In order to remain employed, professors are usually expected to produce a certain number of publications each year. These publications are then peer-reviewed by others in similar fields, and finally published by academic journals and periodicals. This work is all done for free, in the eyes of the eventual publisher; they have a high-quality piece of academic literature turn up, already edited and fact-checked, and decide whether or not to publish — and then, ultimately, how much to charge access for it. It’s not like the authors get a cut.

If you think this is a ludicrous practice, you’re not alone. Early this year a British academic wrote a galvanizing blog post about it, and unknowingly tapped into #academicrage. He promised his audience he would refuse to peer review submission for Elsevier, a huge journal publishing company, and soon enough thousands of academics joined suit. There’s a website to keep score with so far 12,792 researchers signed up. This is the kind of progressive academic activism that most people from across the political spectrum should be able to get behind, and indeed that’s kind of how it’s turned out, with the British government deciding in July to listen to their local academic community:

The government is to unveil controversial plans to make publicly funded scientific research immediately available for anyone to read for free by 2014, in the most radical shakeup of academic publishing since the invention of the internet.

Under the scheme, research papers that describe work paid for by the British taxpayer will be free online for universities, companies and individuals to use for any purpose, wherever they are in the world.

The rest here. Whether or not it’ll start a global trend remains to be seen, but baby steps.

Rosabel

Adding to that last history of Matt’s, Sir Richard Friend is speaking in Wellington tomorrow and it’s a talk I’d definitely recommend attending. This is especially true if you work in academia: this isn't simply a Cambridge physics professor sharing the incredible implications of his research. It’s also an exploration of those points at which industry and academia can and don’t intersect. It’s a topic rarely spoken about – it’s distasteful, somehow, to think about the commercial benefits of your research. To talk about it is virtually unheard of. And you notice it, in the way that he speaks and in the way he’s received. At times he takes on a defensive tone, which is ridiculous because it’s simply not necessary. And yet, on more than one occasion, I actually found myself silently groaning as he returned back to a discussion of his companies, because what I really wanted to hear about was his research. It becomes a confronting experience, but in a way that makes you question these kinds of kneejerk reactions.

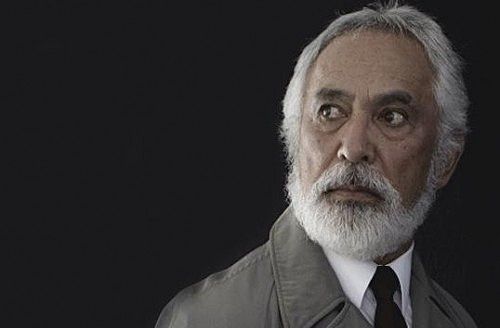

Staying off the grid, Death of a Salesman is currently on at the Maidment Theatre, and George Henare is simply incredible as Willy Loman. Truly. Your heart aches for the entire two-and-a-half hours. And there’s something remarkably unique about seeing a play you know this well onstage – and a lot of people will know it, by virtue of being force-fed the key themes day after day in a high school English class. But there’s this fascinating added layer: you recognise those page-long stage directions, those key lines, and somehow it becomes more about a well-told story; it’s like greeting an old friend and examining their face for those miniscule changes, the parts you don’t recognise, the parts that seem more beautiful than you remember.

And the ever wonderful Kate Beaton on how to spot a feminist: