Internet Histories | 13 May

This fortnight: Playing the taxonomy game, communicating depression, African urban geographies, the Aaron Gilmore Conspiracy, defining the video game, Charles Ramsay and the memeification of tragedy and poverty, and a warm welcome to James Dann

This fortnight:

Playing the taxonomy game | Communicating depression

African urban geographies | The Aaron Gilmore Conspiracy Theory

Defining the video game | Discovering modern Ben Elton

Charles Ramsay and the memeification of tragedy and poverty

and a very warm welcome to

James Dann

Matt

There’s a special kind of outrage reserved for getting taken in by a convincing lie. It’s not only directed outward, but inwards too, a small and formless voice that nevertheless keeps screeching YOU ARE A MORON.

Successful lies play to our fears and hopes, and since there's nothing more terrifying than the existential threat of being removed from the world and leaving not a trace or a memory behind, the busy lie-factory that is our contemporary internet gets the most mileage out of inventing people who have never existed.

The best one I've come across recently is this immaculately detailed story of a Russian director who died in 1960 but was invented in 2002.

The drinks and exhaustion sparked their imagination. They tossed out fantastic hypotheticals, wondering what kind of director would "shoot an insane amount of material, more material than anyone could ever watch," as Ducker later recalled. "What kind of person would shoot an endless film, just never stop shooting?"

The two friends were forging a fascinating character—a fictional marriage of legendary Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky and control-freak geniuses like Stanley Kubrick, an archetypal director slowly creeping into madness. Or as Ducker described him, "a slightly psychotic person. And a slightly manipulative person." They were creating Yuri Gadyukin.

There’s actually a professor in the States, one T. Mills Kelly, who teaches an undergrad course named Lying About the Past. Each year the students in his class are tasked with inventing convincing lies and misleading as many people as possible. Last year they managed to start a Wikipedia edit war (“Things like that really, really, really annoy me,” raged Jimmy Wales, really, really, really forcefully). But I mean, what sort of a name is T. Mills Kelly? George Mason University, the school he’s supposed to teach at, has ‘Where Innovation is Tradition’ as their motto. Their student email server is called ‘Patriot Web.’ Is this a real university? Is he a real professor? Did The Atlantic just make the whole thing up to continue the joke? This is some liminal indeterminacy shit right here. If T. Mills Kelly were to rename his paper ‘Schooling schmucks: internet epistemology and u’, that is a MOOC I would sign up for.

Not that big hoaxes were invented contemporaneously with IP protocols; I’m currently reading Foucault’s Pendulum, a book about playfully creating complex lies, getting caught up in them, and eventually, unwittingly, coming to believe them. Eco nails it:

That day, I began to be incredulous.

Or, rather, I regretted having been credulous. I regretted having allowed myself to be borne away by a passion of the mind. Such is credulity.

Not that the incredulous person doesn’t believe in anything. It’s just that he doesn’t believe in everything. Or he believes in one thing at a time. He believes a second thing only if it somehow follows from the first thing. He is near-sighted and methodical, avoiding wide horizons. If two things don’t fit, but you believe both of them, thinking that somewhere, hidden, there must be a third thing that connects them, that’s credulity.

Rosabel

In psychology, it’s not often you’re exposed to personal stories of depression. Oh, you know the diagnostic criteria. You know those by heart. You know its neurobiology and the standard therapeutic approaches. You learn about maladaptive thinking patterns, rumination and how to identify the kinds of core beliefs that need addressing, but it’s rare that you’re given time to pause and engage in the act of empathy. Don’t get me wrong: you know how to seem like you’re empathising, but in terms of actually understanding what it means to be depressed, opportunities for this are rare.

That’s not necessarily an indictment on the way psychology is taught. Well, no, it is. But it’s also a reflection of the fact that, quite wonderfully, as a society we’re able to talk about it openly and often. The one pitfall of this is that the word can become a heuristic for an experience we’re all expected to understand - particularly since it’s a mood disorder and we all exist on the spectrum somewhere - and in some cases, it’s just plain misused. It’s also, of course, very hard to describe. David Foster Wallace touches on this in Infinite Jest:

It goes by many names - anguish, despair, torment, or q.v. Burton’s melancholia or Yevtuschenko’s more authoritative psychotic depression - but Kate Gompert, down in the trenches with the thing itself, knows it simply as It… It is also lonely on a level that cannot be conveyed. There is no way Kate Gompert could ever even begin to make someone else understand what clinical depression feels like, not even another person who is herself clinically depressed, because a person in such a state is incapable of empathy with any other living thing. This anhedonic Inability to Identify is also an integral part of It. If a person in physical pain has a hard time attending to anything except that pain, a clinically depressed person cannot even perceive any other person or thing as independent of the universal pain that is digesting her cell by cell. Everything is part of the problem, and there is no solution. It is a hell for one.

The return of Hyperbole and a Half is fantastic news not only because it’s the most absurdly charming blog on the internet, but because it returns with an incredibly clear and utterly compelling account of Allie Brosh’s struggle with depression. Everybody should read this. Everybody.

Also recommended is David Foster Wallace’s The Depressed Person, which is more weatherless and difficult to read, but of course this is exactly the point.

I'm naively looking forward to Baz Luhrmann’s attempt at The Great Gatsby, want so badly for it to be great, and am refusing to read any reviews of the film until I've seen it. I have no qualms about reading this selection of one-star Amazon reviews of the book, though:

O.K. the first red flag was that this book isn’t part of any series.

IT IS VERY COMPLICATED TO UNDERSTAND AND THERE ARE A LOT OF CHARACTERS.

I AM STILL READING THE BOOK SO MAYBE IT WILL GET BETTER.

All the characters did was moan about their lives and do stupid things.

It’s boring.

It’s futile.

It’s dumb.

There are murders, but not very unique ones.

Bronwyn

Like cities all over the world (hello, our new friend the Auckland Unitary Plan), the cities of Africa are dealing with urbanisation and a burgeoning middle class in need of somewhere to live; keen to separate themselves from the messy realities of old cities, there's a whole lot of "New Cities" being built to house them, over which the Informal City Dialogues blog sounds a warning cry:

What is worrying is that there is little recognition of place, economy, context and even poverty in these cities. This begs several questions. To whom do these cities belong? Who is planning them? Are they inclusive cities, or simply profit-driven businesses?

Many New Cities are being built with input exclusively from architects, engineers and property developers... For example, Tatu City in Nairobi is set to be developed on prime agricultural land. This land was initially a coffee plantation, which happens to be an important foreign exchange earner for Kenya.

One of the most notorious of these New Cities is the Chinese-built Nova Cidade de Kilamba on the outskirts of Luanda; built to house 500,000, it appears to be largely empty. Luanda is reguarly cited as one of the most expensive cities in the world; the combined effects of a twenty-seven year long civil war that decimated local food production, manufacturing, and transport infrastructure, and an influx of foreign companies chasing the oil dollar since the conclusion of said war, has resulted in a cost of living in the city that is eye watering at best, and life endangering at worst:

To offer his children a safe and clean environment, he may decide to rent a house in one of Luanda’s new distant suburbs, Luanda Sul. A 3-bedroom house with garden in a guarded condominium will cost his oil company at least $12,000 per month. Another good deal. In 2008, the price would have been $23,000 USD. His children’s international school, $40,000 USD per child per year, will also be at his employers’ expense. It reportedly costs an average international company operating in Angola $1 million USD a year to settle an expat in Luanda.

Although public healthcare is free, services are limited, which means many Angolans resort to private healthcare:

...Angolans pay $80 to $150 USD for a simple malaria treatment, $200 to 300 USD for a complicated malaria treatment and about the same for the treatment of typhoid fever. Do these hospitals offer quality care? Perhaps the figures speak for themselves. Infant and maternal mortality rates are among the highest in the world, and average life expectancy at 51 is still among the lowest even though Angola’s (official) 2% HIV prevalence rate is extremely low compared to its neighboring countries.

Those trumpeting the release of more land for more development in Auckland, and talking up a new city in Manukau, only need to have a quick squiz at the images of Kilambra to see what happens when planning goes wrong; it's generally held that its failure is because it's too expensive for locals to buy apartments there, and too far away from the buzz of cosmopolitan downtown Luanda to be attractive to ex-pats who could afford it.

James

I'm not sure if it's quite a conspiracy, but there's certainly been talk that Aaron Gilmore is a deliberate smokescreen - one with a wet-dog mullet and a grossly-inflated sense of self-worth. The theory is that the Gilmore revelations have distracted the media from covering the new GCSB laws, which I don’t really buy because it feels like the media aren’t reporting the increased surveillance powers for other reasons, too. That being said, I can see why they’d want to cover his demise. It’s fun. There have been new bits of information every day or so, dripping out suspiciously just when we think the story has run its course. The last time there was a media event like this was the GCSB/Ian Fletcher shemozzle, and before that, GCSB/Kim Dotcom. It seems like the media are only concerned with the GSCB when you throw in a childhood connection of John Key or an oversized German, but not when it could lead to the surveillance of any New Zealander. Maybe they genuinely don’t think it’s an issue. Or you could consider, as Danyl McLauchlan has at the Dimpost, the reaction of the MSM to the Electoral Finance Act under the last government.

Thomas Beagle at Techliberty has a summary of the communications part of the bill which is a little concerning. Credit must also go to the Herald’s most internet-literate writer Toby Manhire for at least trying to raise the issue in the broadsheet. Apart from a few people in the echo-chamber of twitter, it really doesn’t seem like anyone cares about this bill, not even the government who are ramming it through under urgency. Maybe brainless and impatient weren’t the right words to describe the media, but they’re probably more pleasant than some of the other words I could have chosen: negligent, complicit, oblivious.

Adam

Video games, huh? How about them.

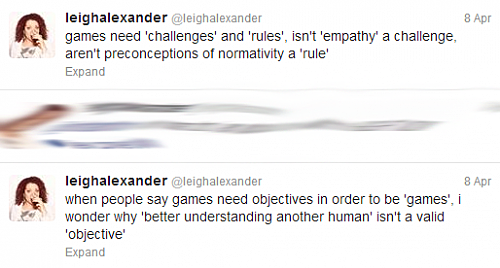

Leigh Alexander, editor-at-large at industry site Gamasutra, is a pivotal figure in modern games writing, prominent in her advocacy for criticism that treats games as expressions of political/social/personal/spiritual identity as well as systems of rules and goals interacting with aesthetics (her piece on Colossal Cave for RockPaperShotgun is pretty much the perfect entry to her work). Raph Koster's a game designer who earned his stripes on Ultima Online and Star Wars Galaxies, a man who obviously knows his shit.

Together, they've inadvertently started a persistent blogosphere shitstorm.

The facts are these: In early April, Alexander tweeted the following -

Koster questioned Alexander’s position with ‘A Letter to Leigh’, a lengthy and thoughtful analysis of what, for him, constitutes a ‘video game’. To Koster, games are a conversation between player and creator, and the ‘art games’ he refers to, games like Dys4ia, Train and To The Moon, lack the ‘gameness’ that would make them ‘games’. ‘Gameness’ is contingent on agency – the ability to ‘argue’ with the game and ‘maybe change its mind’ – and compromising that agency for rhetorical purposes sacrificing the necessary element of dialogue. It’s not that these games are bad, Koster says – it’s that they’re different.

Alexander replied in full in a blog post titled ‘Definitions’. She acknowledges that she agrees with Koster’s belief that games are fundamentally a dialogue, but questions whether Koster’s ‘art games’ really do sacrifice that conversation:

And I think some of the games we’re discussing simply offer us new forms of agency that we haven’t seen before — the ability to pace ourselves through the conversation, to interpret, to choose points of empathy. These are meaningful choices that the system the author’s chosen makes available to me. If I play someone’s game, and I feel I have engaged with them, and I feel something in me move and respond, I feel I’ve had a conversation, an interactive experience.

Then Tadhg Kelly posted 'Formalists and Zinesters: Why Formalism Is Not The Enemy' - less a contribution, more a whine about being 'victimised' because of his assertions as to what games are. He avoids meaningfully engaging with the political implications of creating and policing taxonomies, and it leans on a definition of game that demands 'the joy of winning while mastering fair game dynamics' and scorns mere participation and dialogue. It's passive-aggressive, stubborn and full of generalisations; funny, given that he's trying to call out 'zinesters' who do the same.

Unfortunately, Kelly's response is the one that's come to define discussion, as summarised in this helpful Critical Distance round-up (Craig Bamford's response is my favourite). More recently, though, Matthew S Burns at Magical Wastelands weighed in with 'Our Immiscible Future', a reflection on the fracturing that was part-cause and part-product of this mess. It's a surprisingly funereal overview of the interplay between commercial developers, modern 'indies' and 'zinester' subculture, something he admits, but it's compelling in how it builds off a hopeful statement made in 'Definitions' -

It’s not that I’m pressing for All Things Artful to be defined as “games.” It’s simply that I think the definition discussion distracts from the ways we see interactivity being able to give creative voice for so many. To allow them to have those conversations through a medium, and the medium is designed interaction. In other words, I don’t care what things are called, but I think all kinds of designed interaction can have a place at our table, can have things to teach us.

I agree quite strongly with Alexander here. Definitions can be fun, but their formulation can result in loaded decisions that shut out certain types of voice and experience when we should be doing all we can to help develop those voices and present those experiences. It's telling that, of the reasons Kelly gives for Koster's 'art games' not being games, one is that they represent such a challenge to the status quo that they'll never gain mainstream traction. It's almost as if there's a value judgment there.

Ben Elton's latest sitcom, The Wright Way, premiered on the BBC late last month. It was savaged by critics, for good reason. It's grotesque and shambolic, indistinguishable from any parody of sitcom excess. It's also totally baffling, constantly contradicting itself and the messages it wants to send. On one hand, it's a sitcom custom-built to make a certain type of middle-aged middle-class white man feel comfortable. Through his volatile lead, council bureaucrat Gerald Wright (David Haig), Elton fires off archaic, overwritten broadsides at women, inconvenient technology, health and safety practices, millennials, customer service, male grooming, people who aren't white, and women, and the majority of these pot-shots stand unchallenged. The show's thirty years out of date, something reinforced by the hacky pratfalls and dirty acronyms that make up the rest of its 'comedy'.

On the other hand, the only reasonable character in the show is Gerald's twenty-something lesbian daughter, Susan, an electrician who goes out of her way to help Gerald through his recent divorce. Meanwhile, a world of pain and humiliation is visited upon Gerald, and all he does is moan and antagonise people, hurting himself more in the process. Gerald's the author of his own misery, but it's hard to tell how much Elton wants us to think he's earned it.

Regardless of this, The Wright Way is terrible and Elton's a shadow of the man he once was. The Elton who railed against sitcom sexism in the 1980s now peddles it for a couple of extra quid; the Elton who constructed witty, whip-sharp dialogue for Rowan Atkinson and Tony Robinson now operates as a pratfaller-for-hire; the Elton who used The Young Ones, Blackadder, Stark and Gridlock to critique the Thatcher orthodoxy is now too happy to bemoan government micromanagement.

Elton's been like this for a while. But I didn't know that. As a gawky idiot teen, Elton was a kind of an idol. I cherished the Blackadder repeats on TV One and devoured Dead Famous, Gridlock, Popcorn, This Other Eden, Blast From The Past and Chart Throb in quick succession in 2005 and 2006. His work resonated - the selfish and unpleasant characters, the cynicism towards a world built on self-interest and petty grievance, the tempered humanism underscoring it all. I'm not understating his impact - hell, Gridlock left 15 year old me genuinely angry (and ill-informed) about Big Oil. His work clued me in to political and social discussions I wasn't aware existed, and his influence still carries.

The Wright Way left me exhausted and betrayed. It was the final nail in the coffin of a man I once adored, a man I held up as an intelligent, entertaining, righteous comic idol. The same attitudes and jokes I fell in love with seven years ago are on full display here - but now they look ugly to me. All it took was getting older.

*

Speaking of dying idols, Dave Anthony and Greg Behrendt had notorious comedian/watermelon-smasher Gallagher on their Walking the Room podcast. Gallagher's downward spiral into an aggressive, burnt-out husk of a comedian has been well-documented, and Anthony and Behrendt try to go beyond that. They meet him as they would any other guest, and the result is devastating. He owns nothing and thrives on distancing himself from others. Death preys on his every thought. He's not a husk - just a sad man battling his own irrelevance.

*

Some other good stuff from the interwebs - Martin Amis' hilariously terrible 1982 book about video games; a game about collecting candies and Leigh Alexander's astute observations about what it says about social gaming; and a gem from the Internet Wayback machine, the website of Brendan Horan, NZ First MP and MC for hire.

Joe

Last week’s discovery at 2207 Seymour Avenue, Cleveland was always going to make international headlines. Loved, missing and presumed dead, found again, with the narrative tumult of disbelief, relief and then a yawing, awful horror. It’s the kind of thing cowled editors would try to summon into being over a stone tablet with the sacrifice of an intern, and I don’t really blame them.

However, the subsequent treatment of neighbour Charles Ramsey, one of two men who discovered and rescued the three women, felt like a weird and inappropriate moment in the Internet’s continued memeification of all living matter. Partly because it’s because about a dozen people attempted to Autotune (or Songify, or whatever) the aftermath of three people getting raped and tortured for a decade, and partly because it feels like we’ve seen a lot of poor black eyewitnesses turned into macros and dubstep remixes lately.

Salon put a finger on my unease first:

Granted, the buzzworthy tactic of reporters interviewing the most loquacious witnesses to a crime or other event is nothing new, and YouTube has countless examples of people of all ethnicities saying ridiculous things. One woman, for instance, saw fit to casually mention her breasts while discussing a local accident, while another man described a car crash with theatrical flair. Earlier this year, a “hatchet-wielding hitchhiker” named Kai matched Dodson’s fame with his astonishing account of rescuing a woman from a racist attacker. But none of those people have been subjected to quite the same level of derisive memeification as Brown, Clark, and now, perhaps, Ramsey—the inescapable echoes of “Hide yo’ kids, hide yo’ wife!” and “Kabooyaw,” the tens of millions of YouTube hits and cameos in other viral videos, even commercials.

It’s difficult to watch these videos and not sense that their popularity has something to do with a persistent, if unconscious, desire to see black people perform. Even before the genuinely heroic Ramsey came along, some viewers had expressed concern that the laughter directed at people like Sweet Brown plays into the most basic stereotyping of blacks as simple-minded ramblers living in the “ghetto,” socially out of step with the rest of educated America. Black or white, seeing Clark and Dodson merely as funny instances of random poor people talking nonsense is disrespectful at best. And shushing away the question of race seems like wishful thinking.

Vlogger Jay Smooth makes some wonderful succinct points on top: he calls time on about three years too many of bad, cackhanded free software Autotune jobs on the most obvious of source material (admittedly, we got some highpoints at the start: here’s the video YouTube says I’ve watched the most). He loses the ‘harrumph’ tone of Salon, because sure, Ramsay was pretty good when you got him in front of a camera. But then he wraps up with this:

Charles Ramsay is a funny person, but he’s a real person, who at least on that day had a well of integrity and passion that made him worth talking about. And the more we take people like him and keep running them through the viral meat processing plant over and over…I worry that we’re filtering out whatever is real and valuable about people. I feel like we as a culture turned some kind of corner when the word ‘meme’ became a verb that described something you do to a person. I just think that’s kind of weird, and we might want to pause periodically and look on the path we’re on with that, because it’s taking us to some weird places.

You could push that boat out further and wonder what we’re doing to whatever the situations are – individual, or systemic – those memes arise out of. Eyewitness accounts and testimony have a place and a purpose in news reporting – take them out of it and the results are the sort of medium-to-message spaghetti junction McLuhan didn’t see coming. Especially as video crews grow more web-savvy, and finding ‘talent’ like Ramsay, even in the middle of a crime scene, takes a greater priority than ever before.

Anyway, Ramsay also has a nasty domestic violence record, which he would have had whether or not he happened to help save three people’s lives and go on television in the heat of the moment. Causation doesn't equal narrative, wishing just makes it so – with that in mind, let’s not get into that huffy undirected sense of betrayal having rooted for the guy, or that tedious arc of redemption, shedding skins, “this marks a break from the past” news-cycle hagiography. I liked what Liliana Segura had to say for The Nation:

Some criminals, like some heroes, are allowed to be complex, as we are reminded in the wake of mass shootings committed by white men who are immediately scrutinized for signs of mental illness. Confusion and debate over what Ramsey really is—criminal or hero (or jolly Internet meme)—shows how little complexity we afford people like him. It may have taken an extraordinary action, the saving of three white girls, to make him worthy of people’s collective empathy—and it’s certainly likely that if his criminal record included, say, first-degree murder that this empathy would largely evaporate. But if we more broadly applied the logic of legions who have leapt to his defense as a changed man, if we started thinking that more people might be worthy of a second chance, we might start to change the conversation around prisons and sentencing.

Actually, on prisons: the best piece of TV I saw last week was Campbell Live’s feature inside Rimutaka Prison. Patient, compassionate, informative and underwired with a sort of steely pragmatism that felt like a challenge to the Xtra-accounted, law and order hordes: these people are going to be freed one day, whether you like it or not. What kind of society do you want for them when they walk out? One they reoffend in, or one with second chances?

More than once in its 11-minute runaround I had to turn around and exclaim “it’s still going! They’re still going!” This is a good thing, particularly when Seven Sharp can’t even give our salty, salty diets the 5 minutes grace they deserve. They’re all still beggars when it comes to any possibility straightforward embedding, though.

Finally, to commemorate my getting a new phone this week: the year is 2013, and here is one-time presidential hopeful Newt Gingrich doing his best “What’s up with that?” about cellphones. Stay tuned, though – it sounds like these things have some potential!