Inside Looking Out: Miranda Harcourt on 'Verbatim' and 'Portraits'

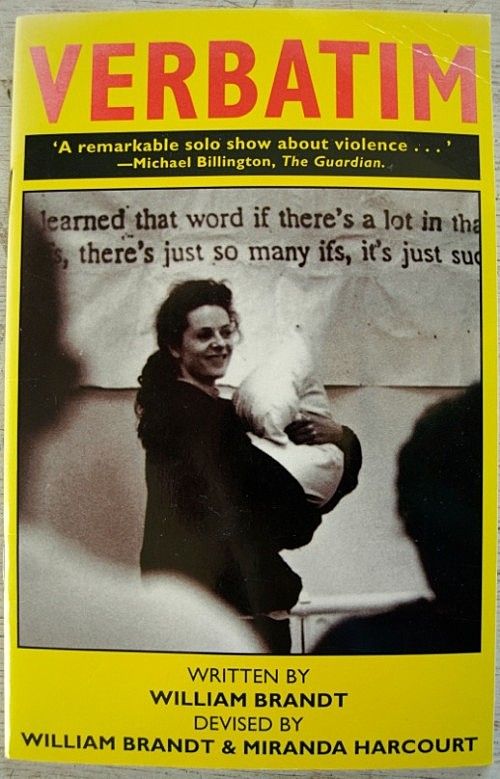

Twenty years after it made its debut in a Wellington women's prison, William Brandt, Stuart McKenzie and Miranda Harcourt's searing 'Verbatim' is being paired up with its follow-up, 'Portraits', and performed in Auckland, Manukau and Wellington. Di White talks to Miranda about why and how both plays were made, and still matter.

Miranda Harcourt has spent a lot of time in prisons. Women’s prisons, men’s prisons, prisons in Australia, prisons in the UK, and, to the best of her knowledge, every single prison in New Zealand. It was 1993 when Miranda and writer William Brandt set out to devise a play using the words of offenders of violent crime, their families and partners, and the families of victims. They went into prisons and homes, conducting dozens of interviews to get the stories of violent crime from those who have truly felt its effects: stories of destroyed lives, lost potential and deep regret.

Verbatim tells the story of a murder: a 22-year-old guy, Aaron, who has gone from doing small-time burglaries (the first of which was when he was just four years old, as he was pushed through a toilet window so he could go and open the front door for his brother) to murdering a woman who catches him robbing her house. The play recounts the murder – the lead up, commission and aftermath – from the perspectives of Aaron, his former de facto partner Sheree, his mother May, his sister Danica and the husband of the woman he murdered, Robert. The play is performed by a sole actor, who was originally Miranda, a choice that from the outset breaks down the villain-victim dichotomy and blurs the lines between victim and offender.

The story, devised entirely from the words of around 30 interviewees and depicting real stories, was not something William and Miranda went into the project looking to tell. Instead, she describes it as a responsive piece: they had been given permission for the project from the then head of the prison system (and, until recently, director of Rethinking Crime and Punishment), Kim Workman, on the basis that they would simply come into the prison and listen to anyone willing to tell their story. “We went into the prisons to find out what the story was that we were going to tell, and that was the story that emerged from the material we collected”, she recounts. “Not only the content, but also the form emerged from that content. We didn’t go in having decided we were going to make a solo show. Form emerged from the experience of the prison system.”

It’s no surprise that this form – a verbatim-style piece with a sole actor – was what emerged. The voices of prisoners, and indeed their family and loved ones, are some of the least heard or understood voices in society. We live in a society that almost collectively turns its back on once that person has been convicted of a crime. Often there is little interest as to why they are there; what events and circumstances – often over an entire lifetime – conspired in a way that murder seemed like the best – or at least, the only – option at the time. While we remain fixated on dehumanising offenders, gratuitously depicting every gory, salacious detail, we so often miss the real, far more complex story.

Miranda describes the story of Verbatim as a “page 4 story”, as opposed to a front-page murder story. It’s not a “whodunit”, like the cases of Mark Lundy or a David Bain, or a mass shooting in a sleepy town: “It was really just a fuck up,” she says. “He didn’t mean to kill that lady. And again and again and again we met those guys.” She describes the act itself as a by-product of a crime gone wrong: “It’s not a murder that began with an intention. It’s like a drunken episode that turned into a burglary for no particular reason, but then transitioned into a murder and then transitioned into a lifetime of either regret or remorse.”

Verbatim opens with Aaron telling the story of his first get away from the Police. He’s age 13. It also happens to be the story of how he learnt to drive. Prisons act as a repository for stories like these: stories of childhoods destroyed by child abuse, alcohol and drugs, and social exclusion. Often, they are also childhoods of undiagnosed learning difficulties, poverty, youth offending. and in the context of country where over 50% of the prison population is Maori, the long and oft-overlooked scars of colonialism. These factors don’t act as excuses; but often they act as explanations. There are a lifetime of reasons why I sit here writing about crime rather than committing it, and in much the same way, there is often a lifetime of reasons behind why someone falls into a life in the NZ criminal system. To Miranda, Verbatim is more a life history than a play solely orientated around a murder.

If Miranda never set out to tell the story of a murder, she most definitely didn’t set out to tell two. It was ten years after the first performance of Verbatim that Miranda, with her husband Stuart McKenzie, returned to the prison system in search of another story. Again, the form was in no way predetermined. After undertaking more interviews with offenders, their families and the victims’ families, one story emerged that Miranda felt they simply had to tell.

“Portraits is about a murder but really it’s about a rape because it’s a play about a twisted sexuality that then ends up in an ‘oh fuck, I’ve murdered her’. That’s what I imagined; it was always about a rape and the murder was just a clean-up operation. The murder is kinda like throwing up the fish and chip paper – it’s an afterthought.” It’s a play that’s difficult to receive as an audience, and, for Miranda, it was a difficult story to tell. “We didn’t chose that story, that story chose us. It emerged and you can’t really turn your back on that story. It’s just such an amazing collection of people,” Miranda says. “It’s such a mythic, classic story; it’s kind of a foundation story of the dark psyche of New Zealand.”

*

When Verbatim opened back in 1993, it was not to a packed audience of seasoned theatre-goers: it was in a room full of prisoners at Arohata Womens’ in Tawa. Over the next three years, Miranda travelled to every prison in New Zealand at that time – 22 in total – and performed the piece to audiences made up of some of New Zealand’s most violent and serious offenders: people convicted of everything from murder to rape to armed robbery. The play was later taken to prisons in Denver, Colorado and the United Kingdom. Festivals, too – though it’s doubtful the experience would have been as knuckle-edge for either the actress or most of the audience.

The performances, documented in the documentary Act of Murder, brought theatre into the prison and told a story to which many prisoners were able to personally relate. “When we took Verbatim through the prison system, so many men – and women – came up to us afterwards and said ‘oh, it so reminded me of my father, my son, my cell mate, my nephew’,” Miranda recounts. “Sometimes they’d even say, ‘It so reminds me of me’. And that was kind of the point: in its specificity, it achieved universality.”

For many prisoners, the reminder of what they had done was difficult to watch. Miranda recounts going into a prison in New South Wales, where she also toured Verbatim. She describes a large, metal bench with a tap that when turned on made a loud noise and splashed all over the bench. When performing, she noticed that one particular inmate was turning on the taps every time Robert (the husband of the murdered woman, Gail) spoke. “He’d run the taps all the way through Robert talking and then, when he could see I’d turned my position and another character was talking, he’d turn the tap off. As an actor, it is so amazing to encounter that audience behaviour: ‘Shut up, I don’t wanna hear you talking so I’m going to create a really, big fucking noise so no one can hear you.’”

While no doubt many prisoners struggled with being confronted by the words of their victim’s partner, there was one voice above all others that they wanted to hear: that of their mothers. It is these voices – that of Aaron’s former partner, his sister, and his mother – that are some of the most striking and indeed heartbreaking of the play. Aaron’s mother, May, recalls the moment she found out about her son’s crime – ironically, in the very same almost clichéd lines with which we associate a parent getting the “knock at the door”. It’s a perspective rarely seen or understood: the pain, the guilt and the regret felt by the mother of a convicted murderer. As the play unfolds, so too do the “invisible” victims of violent crime: the parents, child and partners of the offender, whose lives too are left in pieces as a result of a crime they did not commit.

First touring Verbatim, Miranda took the play not only to prisons but also to schools and to more traditional theatre audiences. In both schools and prisons, Aaron emerged as the “hero”, the character with which audiences related and sympathised. However, traditional theatre audiences – those who are largely middle class, wealthy and white – were far more sympathetic to Robert, Gail’s husband. Miranda recounts performing Verbatim at The Watershed Theatre in Auckland on the night that Jim Fletcher, a wealthy Auckland businessman part of the Fletcher family, was murdered in Papamoa on New Year’s Eve in 1993. It was a murder very similar to the one described in the play: Jim Fletcher came downstairs and surprised the man robbing his house and he was stabbed. “Performing Verbatim in Auckland the night Fletcher was murdered, you could feel the rage in the audience and the hatred towards Aaron.” It’s anecdotes like these that highlight the fact Verbatim is very much a real story.

*

Prison theatre, or theatre in prisons, is a well-established genre heralded for its rehabilitative and therapeutic qualities, both in its telling and receiving. It allows prisoners to explore experiences, be it their own experiences and that of others, through the medium of performance. When Miranda. William and Stuart conducted the interviews with prisoners for both Verbatim and Portraits, they went in not only as playwrights but as confidants. “The deal was we would listen for as long as it takes to tell the story. There was no judgment: we were not lawyers, not psychologists, not sticking our oar in in any way. We just wanted to hear the stories because we were writing a play,” she says. “We found a lot of people who were interested in talking to us because there was no judgment. We weren’t lawyers, psychotherapists or prison officers, there was no input. William and I were just a set of listening ears.”

The play was also therapeutic for Miranda. In the late 1980s, a man broke into Miranda’s home and she was herself a victim of a violent attack. For her, going into the prison system and conducting the interviews was an attempt to understand more from a different experience informed by her own experience. “I found it very therapeutic,” she says, “The guy who attacked me – I never found out who he was – was in the prison system somewhere. So I may well have performed to him, really I don’t care – it doesn’t make any difference to me – although there’s a dramatic irony.”

While there is no “right” response to being the victim of a violent attack, there’s no doubt this is a remarkable one. Sadly, this restorative approach, in which Miranda effectively met her offender over and over again, is one many victims are not even given as an option. Instead, the more common response – one that is encouraged by the way society demonises offenders – is that of hatred and anger. To say these emotions are understandable is an understatement, but what Miranda’s experience – and that of many others who go through the restorative justice system – harbouring these emotions is rarely conducive to moving forward.

Twenty years on from the first performance of Verbatim, and ten years since that of Portraits, you cannot help but feel that the two pieces were defining projects in the career of one of New Zealand’s most eminent stage practitioners. “Verbatim and Portraits were the start of a long journey for me,” she explains, “From the perspective of journalism, poetry, drama, theatre and writing, these plays had a huge impact on my life and my work.” Her commitment and resolve to telling the stories of those behind bars is as strong as ever. “It’s not something to enter into this world and then go ‘Oh, thanks it was really awesome to suck out the blood of the prison system,’” she explains, “It’s really a life long commitment. Verbatim and Portraits were the start of a long journey for me.” Currently, Miranda is working with women prisoners at Arohata Prison in Wellington on a story reading and literacy programme. The women at Arohata come from all over the country, this being the only women’s prison to offer an alcohol and drug programme, meaning many children simply do not get to see their mothers. Miranda goes into the prison with a sound recordist and gets the women to read Joy Cowley books donated by publisher Clean Slate Press. The women write a message in the book, and the CD with the mothers’ voices and the books are sent to their children. It’s a project that recognises the impact imprisonment has on children – especially when it’s the child’s mother in prison.

With 20 years having past, almost all of the people Miranda interviewed and performed to will have been released. While she has not made a concerted effort to keep in touch with any of the offenders or victim’s families, thinking to do so would be “barking up an inappropriate tree”, she’s had a number of encounters with people from the almost five-years she spent in the prison system. “I still sometimes run into people who look at me in a certain way, wearing a particular type of jumper or on the street, and there’s a sense of complicity passes between us, and I know where I’ve met that guy before.” She tells me, fighting off tears, of one former prisoner she met who recently received his PhD. She laughs as she tells me the story of a former inmate who added her on Facebook with a message: “I was in Paremoremo for robbing banks. I haven’t robbed a bank for over 20 years but every time I look at my bank statements I feel like they are robbing me.” Miranda may have taken the stories of people who have undoubtedly committed horrendous crimes, but they are still people. They are people who after they murdered someone went home to tuck their child into bed; they are people who have mothers and children and girlfriends; they are people who resent high bank fees.

If the plays sound uncomfortable, it’s because they are. They are confronting, they are heartbreaking, they are complex and, above all, they are real. Both are messy; there’s no point for disengagement from the plays and re-entry into reality. In this respect, they are exactly what Miranda, William and Stuart set out to do. “It’s not just about performance, it’s actually about engaging with the community,” Miranda argues. “Otherwise, why do it? Why would you just fuck around doing theatre to the same group of 500 people with season tickets all of your life? It’s about finding new audiences and really using your work to engage with new audiences in the community.”

"Verbatim" and "Portraits" are being performed as a double bill at Basement Theatre from 12-16 November, at Newtown Community and Cultural Centre from 20-23

November, and at Mangere Arts Centre from 25-27 November.

The performances are a collaborative project between Auckland-based Last Tapes Theatre Company, and JustSpeak, an organisation of young people pushing for change in our criminal justice system. Starring Renee Lyons (Nick: An Accidental Hero), Jodie Rimmer (Until Proven Innocent, In My Father’s Den) and Fraser Brown (Harry, and the upcoming Field Punishment No.1). Directed by Jeff Szusterman. Visit http://www.iticket.co.nz/go-to/verbatim-2013 for more details.

Di White is part of JustSpeak, and is working with Last Tapes Theatre Company on the 2013 season of Verbatim and Portraits.