If He Could Only Connect: Peak Sorkin, Eisenberg-as-Zuckerberg, and the Inception of Facebook

The Social Network is not so much a zeitgeist-capturing film about a monolithic website as it is a film about loneliness, isolation, alienation and disconnection. As an exploration of our intractably networked age, it is barely a thumbnail sketch—but it is one that is nonetheless fascinating.

[S]ocial networks have always existed, and they have almost always sprouted from an agenda of exclusivity. In 1727, a twenty-one year old in Philadelphia founded The Leather Apron Club, informally known as “the Junto.” He and his friends were a group of likeminded young men who met on a regular basis to discuss the issues of the day, to debate philosophy, to devise schemes for self-improvement, and “to form a network for the furtherance of their own careers,” in the words of Walter Isaacson, the young man’s biographer. The group stood in opposition to the prominent high-society gentlemen’s clubs at the time, and the number and power of its membership would eventually be leveraged to create, among other communal services, a lending library and The Union Fire Company, the latter born of frustration over “the utter lack of any organization for extinguishing fires in the town.”

The Junto even circulated lists of questions not unlike the “25 Things About Me” Facebook notes that were in vogue not so long ago. Among the questions was “Is there any man whose friendship you want, and which the Junto or any of them can procure for you?” So from the start, and even despite the group’s intentionally distancing itself from the élites of the gentlemen’s clubs, Benjamin Frankin’s social network sprang primarily from a need to feel part of an exclusive set, to befriend influential and important people, and to feel needed and appreciated by a collection of peers. If you can’t join ’em, beat ’em: make your own cadre of companions where everyone is of equal stature, and build from there until you become more powerful, collectively and individually, than those you once wanted to be in with. Status anxiety—worrying about one’s position in life—has always informed social interaction, and the development and rise of social networking, coupled with the always-on nature of the Internet, has not only allowed this to continue unabated but amplified (arguably out of all proportion) its importance in forming social ties.

He would eventually amass a network of more than half a billion, but in 2003, when he was a 19-year-old Computer Science undergraduate student at Harvard University, Mark Zuckerberg had just one. One friend, that is. Facebook, his social network, would—as David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin’s film The Social Network tells it—start life as a campus-centric HotorNot.com, an idea sparked by the combination of a few too many Tuesday-night beers, his jilted lover’s stupefied resentment at having just been dumped, and a macho need to show off his ‘hacking’ skills to his friends. In his profile of Nick Denton in the New Yorker earlier this year, Ben McGrath quotes the Gawker magnate as saying that Zuckerberg revealed to him that he had originally planned for the site to be, in Denton’s words, “this dark Facebook… the idea was that it was going to be a place for people to bitch about each other, and then it evolved. It was interesting… how agnostic he was about which approach to take.” Towards the end of the profile, McGrath points to a New York Times piece on the film which quotes Denton again, referring to earlier Silicon Valley hippie-pioneers like Bill Gates, Paul Allen, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak:

What may be different is that in the past, those people have been far more colorful and charismatic. They have embraced that side of themselves. But for people like Zuckerberg, it’s more like Asperger’s, that they lack something essential and don’t have an instinctual understanding of human behavior. That’s why he ended up creating algorithms to explain it.

However misogynistic its beginnings, whatever impulses its founder had to create it, and whatever it might explain about the flaws in his character, Facebook has become a fixture in the everyday lives of hundreds of millions of people the world over. Users spend an average of 32 minutes on the site per visit—some 700 billion minutes a month total—and each page view lasts, on average, 35 seconds. It is the world’s largest photo-sharing website, containing over ten billion images—which number doubles by a factor of at least four due to the site’s backup and storage mechanisms that duplicate each photo multiple times for archival reasons, and so that they are readily accessible around the world. The site serves some 300,000 images every second, and its users upload between two to three terabytes of new images every single day. (What’s perhaps just as astounding about these numbers is that they are two years out-of-date; a brisk Google yields no newer figures.) According to the web-metrics site Alexa, Facebook attracts more unique visitors each day than YouTube, Twitter, Wikipedia, and Amazon.com, making it second only to Google. Fincher and Sorkin’s film doesn’t critique the almost completely unplanned nature of the site’s development, nor does it explore any of the myriad concerns (personal-privacy and otherwise) which have arisen from its existence or the massive societal changes it continues to envision and enact almost unaided. This is why much of the posturing about the film being an all-encompassing illustration of The Way We Live Now (on which more later) is not only silly but completely unfounded. But while the film makes little real attempt to explain the site’s prominence in its users’ lives, it makes of its creation—which could quite rightly have been presumed to be un-filmable—a truly riveting drama.

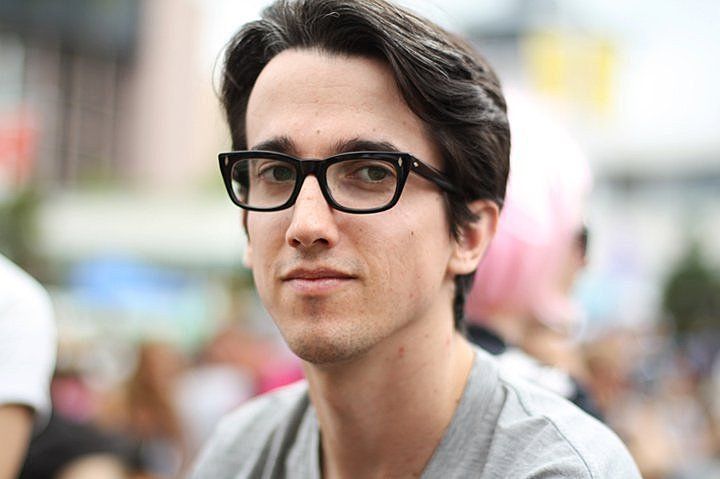

Jesse Eisenberg (The Squid and the Whale, Adventureland) gives one of the best male lead performances of the year in his portrayal of Zuckerberg as an unflinching, unfeeling pseudo-automaton. As the film has it, Mark Zuckerberg is a social autistic, and Eisenberg—who is 26, the same age as Zuckerberg is now—conveys this perfectly: as just one example, like the real Mark, and contrary to what Zadie Smith might have mis-remembered in her appreciation of the film for the New York Review of Books (“Generation Why?,” Nov. 25, 2010), Eisenberg’s eyebrows never move. Seemingly comfortable in his own skin, the real Zuckerberg, as he appears in tv interviews and webcast discussion fora, barely ever emotes—at least not in his face, which is unvaryingly inexpressive—and seems at once cocky and neurotic, indignantly defiant of nothing in particular and defensive of a non-existent attacker. As Zadie Smith points out, when the real Mark gets nervous, he doesn’t get angry or shout, he just sweats. (The spooky TIME magazine cover shot crowning Zuckerberg Person of the Year makes him look alien, lending credence to the conspiracy theory that he is, in fact, a non-human who—almost certainly in collusion with the CIA, and under the supervision of the reverse vampires—is slowly gaining access to all the world’s data.)

[O]wing in large part to Sorkin’s precise, dense dialogue, Eisenberg imbues Zuckerberg with an ominous, ambivalent faux-sincerity: it might seem like he cares what other people around him are saying, but he wishes he could just tune out and retreat to his own little world, “wired-in” to his computer, as he and his fellow programmer-geeks phrase it. Andrew Garfield (Spike Jonze’s I’m Here, Mark Romanek’s forthcoming adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel “Never Let Me Go”) plays Eduardo Saverin, Zuckerberg’s bff and Facebook’s first cfo—his first true confidant, and the only person to whom he initially entrusts the financial goings-on of the fledgling company. The plot concerns the implosion of this friendship, which happily coincides with the social media giant’s phenomenally speedy rise to prominence. An earlier iteration of this digital creation myth was Chris Hegedus and Jehane Noujaim’s 2001 docu-drama Startup.com, a Web-1.0-era tale of the founding of a new media company at the height of the dot-com boom (and bust). But where that film focussed on the friendship at stake in the site’s success or failure, Sorkin and Fincher’s Web-2.0 origin story is told from multiple characters’ points of view as the narrative shifts and continually flashes forward to the two 2008 depositions hearings (in both of which Zuckerberg is defendant) at its core. It is a docu-fiction of the inception of a very recent revolution, one which is still too recent for its ins and outs to be charted with any critical distance or all-encompassing sense of scale—but it is one that is nonetheless fascinating.

The film builds on a sensationalist, deliberately sexed-up unauthorised history of the founding of Facebook by Ben Mezrich, a piece of very creative non-fiction written and conceived, no doubt, with silver-screen and marquee lights foremost in its author’s thoughts. (Sorkin in fact began work on the screenplay in 2008, before the book had even been published; he says he never read written material from Mezrich, and “didn’t get a look at the book until the screenplay was almost finished.”) As his introductory Author’s Note explicates, Mezrich (Harvard ’91)—author, also, of the equally-fabricated “Bringing Down the House,” on which the dismal, pathetically flashy 2008 money-spinner 21 was based—wrote The Accidental Billionaires: the Founding of Facebook, a Tale of Sex, Money, Genius and Betrayal (its title almost certainly deriving from Robert X. Cringley’s excellent history of personal computing, Accidental Empires) without involvement from Zuckerberg:

The Accidental Billionaires is a dramatic, narrative account… There are a number of different—and often contentious—opinions about some of the events that took place… I have tried to keep the chronology as close to exact as possible… Mark Zuckerberg, as is his perfect right, declined to speak with me for this book despite numerous requests.

Janet Maslin, in reviewing the book for the New York Times, calls Mezrich “crass,” dismisses his style as “desperately cinematic,” and condemns his book as “so obviously dramatized, and so clearly unreliable, that there’s no mistaking it for a serious document.” Mezrich is unashamed, even arrogantly proud of what he calls his “thriller-esque style.” In Mark Harris’ account of the film’s creation for New York magazine, Mezrich even goes as far as to pompously align himself with Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe before proposing that his is perhaps a completely new style, a genre that demarcates new boundaries for the fictive-non-fiction hybrid. (David Kirkpatrick’s The Facebook Effect stands, so far, as the definitive clear-headed account of the company’s founding.) Because Sorkin apparently never read the book (not even a single complete chapter), his and Mezrich’s narratives diverge somewhat: where the ordering of Mezrich’s sleazy subtitles betray the trajectory of his vision of the story, Sorkin’s, as it appears through the artifice of the film, is almost the reverse, putting betrayal at the core, and having sex be only a momentary diversion from the real, amorphous goal of containing and conquering the behemoth that is real-world socialisation.

[A]aron Sorkin is famous for the rapid-fire dialogue and the ‘walk-and-talk’ tète-à- tète spiels he gives his characters on the tv series The West Wing, dialogue that is voluminous—probably only Gilmore Girls has a comparable word-per-minute count, and rumour had it that scripts for that show ran to twice the length of a regular 45-minute network dramedy—yet tightly-packed, often imparting multiple plot points in a single sentence. (He saw Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf when he was nine years old, which perhaps goes some way to explaining his frenetic dialogue.) Here, his decision to tell the story from the aforementioned multiple perspectives allows his trademark writing style to impart to us almost too much information. (The shooting script was apparently 142 pages, and the film is only two hours long; by the regular Hollywood measure of a-page-a-minute, this wouldn’t have fitted together if this weren’t an Aaron Sorkin script.)

The film opens with a peripatetic tour-de-force: sometime in 2003, Zuckerberg is sitting across a table from his girlfriend Erica—played by Rooney Mara (Youth in Revolt), whom Fincher has cast in his much-anticipated upcoming remake of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo—at a bar near the Harvard campus. They’re having a heated discussion about a number of things—the number of Chinese with genius IQs, which is apparently more than in the entire US population; Mark’s improbably perfect score on his SATs; the ‘Final’ clubs, which are wasp-y fraternities Mark wants to get into (“Because they’re exclusive, and fun, and they lead to a better life”)—but they’re also breaking up, because Mark thinks he’s “better” than her because he goes to Harvard:

Mark: I wanna try and be straightforward with you and tell you that you might want to be a little more supportive. If I get in [to the final club], I will be taking you to the events, and the gatherings…and you’ll be meeting a lot of people you wouldn’t normally get to meet.

Erica: (Sarcastically) You would do that for me?

Mark: We’re dating.

Erica: Okay. Well I wanna try and be straightforward with you and tell you that we’re not anymore.

Mark: What do you mean?

Erica: We’re not dating anymore. I’m sorry.

Mark: Is this a joke?

Erica: No, it’s not.

Mark: You’re breaking up with me?

Erica: You’re “gonna introduce me to people I wouldn’t normally have the chance to meet.” What the f— What is that supposed to mean?

He insults her further, claiming that the only reason they got into the bar is because she slept with the bouncer, who is actually a friend of hers, and, contrary to what she keeps arguing, condescendingly tells her she doesn’t have to go back to her dorm to study because she “goes to B.U.” (i.e., not Harvard or another ivy-league school). He genuinely believes that she cares as much about status as he does. He apologises (but only “if it seemed rude”) and stops Erica at one point to ask (echoing and doubling up his previous “Is this a joke?” line) if “this” (i.e., the breakup) is “real”—the idea being that he’s unable to read her body language and/or totally distracted by something other than what’s happening right in front of him. “I think we should just be friends,” Erica says. “I don’t want friends,” Mark shoots back—a telling line: he doesn’t want acquaintances; he just wants the power, access and privilege that attend their befriending.

This scene, and another later in the film set at an a cappella group recital at Christmastime, are Peak Sorkin: the dialogue is multi-layered (“Sometimes you say two things at once, I’m not sure which one I’m supposed to be aiming at,” says Erica) and exhaustive (Erica, again, in perhaps a meta-comment on Sorkin’s style: “Dating you is like dating a StairMaster”) and something mentioned at the start of a ‘paragraph’ will circulate and come back around to be answered, re-phrased or dismissed at a later juncture. His script for this film far surpasses his writing on the excellent (and unfairly overlooked) single-season show Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, and is on par with many of the great monologues and all the most enjoyable verbal jousting and sniping in the very best episodes of The West Wing.

Because Zuckerberg coöperated with neither Mezrich nor Sorkin et al., both book and film are very much The Eduardo Saverin story, with every inaccuracy and barbed phrase that caveat entails. After the breakup scene—for which Fincher, in search of perfection, exacted a whopping 99 takes from his actors—the film entertainingly dramatises the inception of the website in a masterful display of parallel editing. Mark jogs back from the bar to his dorm room through the leafy environs of the Harvard campus, where he lifts the lid on his laptop and installs himself at his desk, ensconcing himself once again in his familiar, almost homely lair. He opens his web browser and begins, in one window, an ill-advised LiveJournal rant (taken verbatim from blog-post archives) about how much of a “bitch” his now-ex-girlfriend is. In another window, he opens the online facebook of one of the Houses on campus, and contemplates what he can do to (symbolically) get back at Erica for dumping him—something, in his weasel words, to take his mind off her. One of his roommates suggests putting the pictures “next to photos of farm animals, and having people vote on who’s hotter.” He doesn’t go that far, but he does download all the available photos of female students on campus and creates, at random, false rivalries between them based purely on looks: this is FaceMash. It races across the digital corridors of the university and (literally) becomes an overnight success, in much the same way as “Facebook me” would become a regular expression on campus within only a fortnight of the site’s birth. Zuckerberg gets interviewed the next day in the Harvard Crimson, and begins to taste the fame (and some of the recognition) he was seeking.

On paper, this scene might not have sounded too interesting—hence the aforementioned critique of the story being obtusely un-cinematic—but in the film, Fincher brings it to life, pitting Mark’s hacking theatrics against another kind of spectacle: the arrival, elsewhere on campus, of a busload full of young women trucked in from another college to entertain and delight the men of Phoenix club—one of the final clubs Mark desperately wants to get in to. Powered by decisive, vital parallel editing and spurred on sonically by a propulsive, house-music-inflected score cue called “In Motion,” this sequence is one of the early highlights of the film. Computer ‘hacking’ is never sexy or entertaining, but thankfully Fincher has delivered something closer to the precision of the computing scenes in the otherwise easily-discarded Antitrust, rather than the absurd digital pyrotechnics of The Matrix, Swordfish or, God forbid, Hackers. (The less said about whatever it was the makers of 1995’s The Net were trying to say about the pizza-ordering utility of personal computers, the better.) For a moment, Fincher and Sorkin pull off a feat: they turn a weedy Jewish computer nerd into a rock-star programmer, and though he would be reprimanded by the administrative board at Harvard, the cat was out of the bag: The Facebook was born.

The alternating currents of the film are the two civil suits brought against Zuckerberg, in which he defends two distinct yet similar allegations. The first is the economical and emotional backstabbing of Saverin, a one-two Zucker-punch that resulted in the former cfo’s ownership share in the company being diluted down from more than a third to less than one percent. The second case is one of alleged plagiarism and intellectual-property theft. Two hulking Olympian rowers, Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss (played by one actor, Armie Hammer, doubled via special-effects) alleged that, following his infamy after the FaceMash scandal, they asked Zuckerberg to help them with a site they and their business partner (Max Minghella, Art School Confidential) were building, called Harvard Connection. It would be an online facebook for the Harvard campus, they said. The Winklevii (as Mark geekily labels them) waited patiently as Mark stalled them at every turn, all the while taking ideas that they had given him and putting them to work in the social network he was building, and attaching his name to the copyright notice at the foot of every page. The Winklevii, in Mark’s words, aren’t suing him for intellectual property theft, though, but because, “for the first time in their lives, things didn’t go exactly the way they were supposed to for them.” The two lawsuits inform the retrospective narrative flow for the rest of the film, as Fincher and Sorkin weigh up what they know of the facts with what they were able to glean from official transcripts.

[I]n the third act, another rockstar enters the picture—and this time a real one, not a pasty programmer made to look spectacular via editing. He’s Sean Parker, co-founder of Napster, and, in the year’s best casting decision, he’s played by Justin Timberlake. He’s out at Stanford when he discovers Facebook and decides to head-hunt its creator with plans to woo him into allowing Parker to take an active role in the company’s day-to-day running. (Parker—who in real life looks something like Zuckerberg crossed with Malcolm Gladwell—would eventually become the company’s founding President, a position he retained for several years; he still advises the company in an unofficial capacity.) Parker gets all the jokes, all the girls, and all the best lines. His coke-fuelled ‘Sean-a-thon’ monologues, of which Zuckerberg laps up every word, contain some of the film’s best throwaway lines, such as when he tells Mark to shorten the name of the website: “Drop the ‘The’—just ‘Facebook.’ It’s cleaner.” At a San Francisco club surrounded by actual-club-volume beats, pulsing lights, and with Victoria’s Secret models as dates, Sean, hepped up on goofballs, seduces Mark into letting him into the company, regaling him with stories of his fleeting fame and promising same to his young tyro. Later in the film, after snorting coke out of the belly-button of a 19-year-old intern at a drunken frat party hazy with the smoke of so much marijuana, he makes a grand proclamation: “First we lived on farms, and then we lived in cities, and now we’re going to live on the Internet!”

The film’s supporting characters (especially the miscellaneous legal counsel) are unremarkable and interchangeable, save for a Cheneyesque Douglas Urbanski as Harvard President Larry Summers—to whom the Winklevii plead for assistance in quashing Zuckerberg’s nascent website—and a very good, if transitory, impersonation of Bill Gates by Steve Sires. Sorkin has a cameo as an angel investor, and Rashida Jones plays a lawyer whose raison d’être seems to be to deliver the crucial line of closing dialogue. While Eisenberg-as-Zuckerberg doesn’t sweat like the real Zuckerberg does, he gets almost every other public mannerism precisely right and, in one scene in particular, illustrates what Fincher and Sorkin see as Zuckerberg’s multi-channel mind. Zuckerberg, who constantly looks like he’s staring straight through the person he’s talking to, distracted by some ephemeral logic problem lingering unsolved in the attic of his brain, is sitting in a boardroom full of lawyers across the table from three people suing him. The lawyer for the prosecution asks him a question, to which Zuckerberg replies, in a particularly Sorkinian off-the-cuff manner, “It’s raining…” as he nonchalantly stares out the window. He’s too distracted by whatever’s really weighing on his mind to give any one person in the room his full attention, but he’s aware of his surroundings enough to notice a change in an external variable like the weather. This—the portrayal of a social autistic trying to contort sociality into something he can understand through numbers, algorithms and data—is the film’s great achievement, and it is due in equal measure to Eisenberg’s performance and Sorkin’s script.

But this is as much David Fincher’s film as it is Aaron Sorkin’s. Though it might seem at odds with the gab-happy writing, Fincher’s muscular, accomplished style—which he has been developing since his music-video days and which is here attenuated by the superb work of cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, who also shot Fight Club and performed additional camera duties on Se7en and The Game—actually complements Sorkin’s dialogue, even though he (Fincher) doesn’t have too much room to breathe—or any physical obstacles around which to creatively manoeuvre—because the film’s settings (lawyer’s offices, spare, tech-centric dorm rooms) are so spatially limiting. Fincher isn’t really even able to afford himself his usual flashes of inspired visual fretwork that permeate every overworked hyperreal synapse of Fight Club and show up in the guise of the gta-style bird’s-eye view of a taxi ride in Zodiac—save for what Zadie Smith adroitly observed as the film’s one moment of (literal) showboating: the rowing competition in the middle of the film.

The sequence, which is accompanied on the sound track by a harsh re-working of Edvard Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” shows the Winklevii in competition at the Henley Regatta—more specifically, it shows them losing by a nose, to reiterate the thematic idea that “close is not quite enough,” that, to quote Mark later in the film, if they had invented Facebook, they would have invented Facebook. The sequence, deliberately music-video-like by design and with the original tune’s rhythms blown out into stalking, menacing tones, might impress and even blow the socks off a number of critics for what they might perceive as its visual acuity alone: it uses tilt-shift photography, a technique which employs selective focus and makes life-sized scenes appear miniature. To most viewers, this bit of old-is-new-again lens-trickery is probably fascinating, but to anyone who has spent any time at all in the atomised, ever-expanding hallways of a Google Reader account over the past eighteen months, it’s something that is easily replicated on entry-level prosumer equipment and has been brandished about sites like Vimeo ad nauseam by every would-be Harris Savides in recent months. It’s not only a trivial conceit, but, along with the music, it’s an ultimately distracting set-piece that disrupts the flow and pent-up tension of the narrative.

The score, by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross of the industrial-rock band Nine Inch Nails, is a series of cold, computerised pieces—howling electricity transferred to an aural spectrum—that go hand-in-hand with the precision of Cronenweth’s deliberately flat, solid images. Aside from the Grieg reimagining, it fits the picture to a T, echoing the visuals at every turn. The opening cue, “Hand Covers Bruise,” features a simple piano melody over scratchy, metallic noise not dissimilar to a hard disc in its death throes; these sounds are eventually joined by windy, pre-programmed digital echoes. “In Motion,” the next cue, and the one utilised in the aforementioned parallel-editing scene, is a series of coruscating bleeps, blips and bloops in front of a palpitating robotic beat that shimmer across the film’s soundscape. From here the score vacillates between these two moods: short, plaintive, climbing electronic-piano cues attended by flashes of synthesised light and streaks of drawn-out, subdued-anthemic guitar melodies (as in “It Catches Up With You” and “Intriguing Possibilities”) and fixed, dirty sonic rubbings yearning for collective action, as in “A Familiar Taste,” in which Reznor dumpster-dives through some sort of computer graveyard, and “3:14 Every Night,” which bristles with the caffeine-fuelled tapping of a million keyboards issuing a million immaculate commands. It is the best score of the year, and its only legitimate competition in the Best Score category at the Oscars should be Daft Punk’s score for TRON: Legacy, which out-Zimmers Hans Zimmer in the “barm-barm” stakes.

Aside from a few semi-background tunes like the music that plays in the club, the film’s only use of popular music comes right before the end. Mark is seen hitting refresh on his laptop, waiting for Erica to accept his friend request; the standard bio-pic post-narrative character summaries appear onscreen in sequence as the jangly, Eastern-inflected opening chords of The Beatles’ “Baby You’re a Rich Man” fade in. “How does it feel to be / One of the beautiful people? / Now that you know who you are?” asks John Lennon; Mark, forlorn, passive, and immensely sad, has no answer. “Mark Zuckerberg is the youngest billionaire in the world,” reads the final card, and “Baby You’re a Rich Man” reaches its chorus as the credits roll. Whereas in Zodiac Fincher used Donovan’s “Hurdy-Gurdy Man” as an emblem of the time and place of that film’s setting, here the Beatles tune is shrewdly evocative of the protagonist’s supposed emotional state. This is one of the most perfect uses of a pop song in cinema.

[T]his is not so much a once-in-a-generation zeitgeist-capturing film about the making of a monolithic global-water-cooler of a website as it is a film about loneliness, isolation, alienation and disconnection. But it’s not, despite what its director might think, explicitly about “the loneliness that characterises much of modern interpersonal communication,” because we are not all Mark Zuckerberg. To be sure, this is a film about the many tribulations of just one person, a young man on the outside looking in—a young man who desperately wants nothing more than to be accepted by and connected to those who he sees as wielding and sanctioning power and influence. It profiles an acute brand of seclusion, the loneliness of someone desperately trying to reach out the only way he knows how. But that’s basically all it is, because as a film it makes no effort to dismantle the pervasive, persistent illusion that the site was created with an express purpose and a singular, well-thought-out vision—or to prod its position in the grand scheme of things.

The film is not, as many critics would have it, a blunt, astute précis of the digitalised life in 2010, or a summation of the wants and desires of generation-whatever-they’re-calling-us-now. It’s not an overarching explanation for the impulsive actions brought about by our supposedly over-informed, easily-distracted data-addled brains, as much as its searing, brilliant trailer would like us to believe, via Radiohead, that Facebook provides control and access to “the perfect body”; the “perfect soul”; and, above all, that people will notice us even when we’re not around, no matter how much of a ‘creep’ we might all be. David Denby, in his review of the film, miscategorises Zuckerberg—who throughout the film wears nothing more fashionable than a plain block-colour hoodie over an ordinary t-shirt—as the proprietor of a “hipster business enterprise,” as if the revolution wrought by social media is more fleetingly ironic or any less ideological than, say, the antiwar protests of the 1960s. Zadie Smith comments that, watching the film, “you can’t help but feel a swell of pride in this 2.0 generation…They’ve spent a decade being berated for not making the right sorts of paintings or novels or music or politics.” Mark Grief apparently feels the same way as Smith, because in his “What Was the Hipster?” pamphlet, he catalogues our many supposed generational failings:

The hipster moment did not produce artists, but tattoo artists… It did not produce photographers, but snapshot and party photographers… It did not produce painters, but graphic designers. It did not yield a great literature, but it made good use of fonts.

The film is not an illustration of this apparently semi-illiterate, visually-impelled generation consumed by momentary diversions. (How radically different, anyway, is this supposedly hip generation from their precursors, the slacker-grunge cohort of a decade earlier?) Denby says the film “hints at a psychological shift produced by the Information Age, a new impersonality that affects almost everyone.” I think I might have missed this memo; I don’t feel any less ‘personal’ than I did before the influx of social media—in fact, quite the opposite. The film actually says very little about how and why society is changing; as an exploration of our intractably networked age, it is barely a thumbnail sketch. Smith later says that it “turns out the brightest 2.0 kids have been doing something… extraordinary: they’ve been making a world.” This world is certainly alluring, and its creation is absolutely an entertaining tale, but it is not the be-all and end-all of our generation: we are more than the sum of our digital parts, and I don’t think Facebook will, for most of us, totally replace face-to-face interaction any time soon.

No, The Social Network is ultimately not about the new, but the old: the age-old need for recognition, companionship, and even love. If its protagonist is necessarily derived from a Bella-Swan-like blank slate, it is not because we should project ourselves onto him—though Fincher and Sorkin, at several junctures, absolutely and purposefully render him more than amiable—but for purely dramaturgic reasons: if Zuckerberg didn’t exist, Sorkin would have had to have invented him. The film starts with a disillusioned outsider plotting a way to be accepted by the Porcellian or the Phoenix, reaches its apex with him discovering a way to replace those final clubs and have each of us become king of his own castle, and ends with him, dismayed once again, begrudgingly requesting social acceptance—and an affirmation of his existence—from his ex-girlfriend.

Zuckerberg takes “the entire experience of college” and puts it online because he doesn’t have the tools with which to navigate traditional social encounters, but also and primarily, as that old MAD magazine column goes, simply because he can. He reduces social experience to a set of variables, a singular commodity, in order to study and understand it. Aaron Sorkin’s ersatz Zuckerberg, Mark Harris writes, “is someone who aches to connect, and invents a way to do technologically what he can’t do intuitively.” If he could only connect to people in real life, he wouldn’t need to burrow into a virtual universe. Alas, as Smith points out, “to Zuckerberg, sharing your choices [‘likes,’ etc.] with everybody” is not a supplement for face-to-face social interaction, it is social interaction.