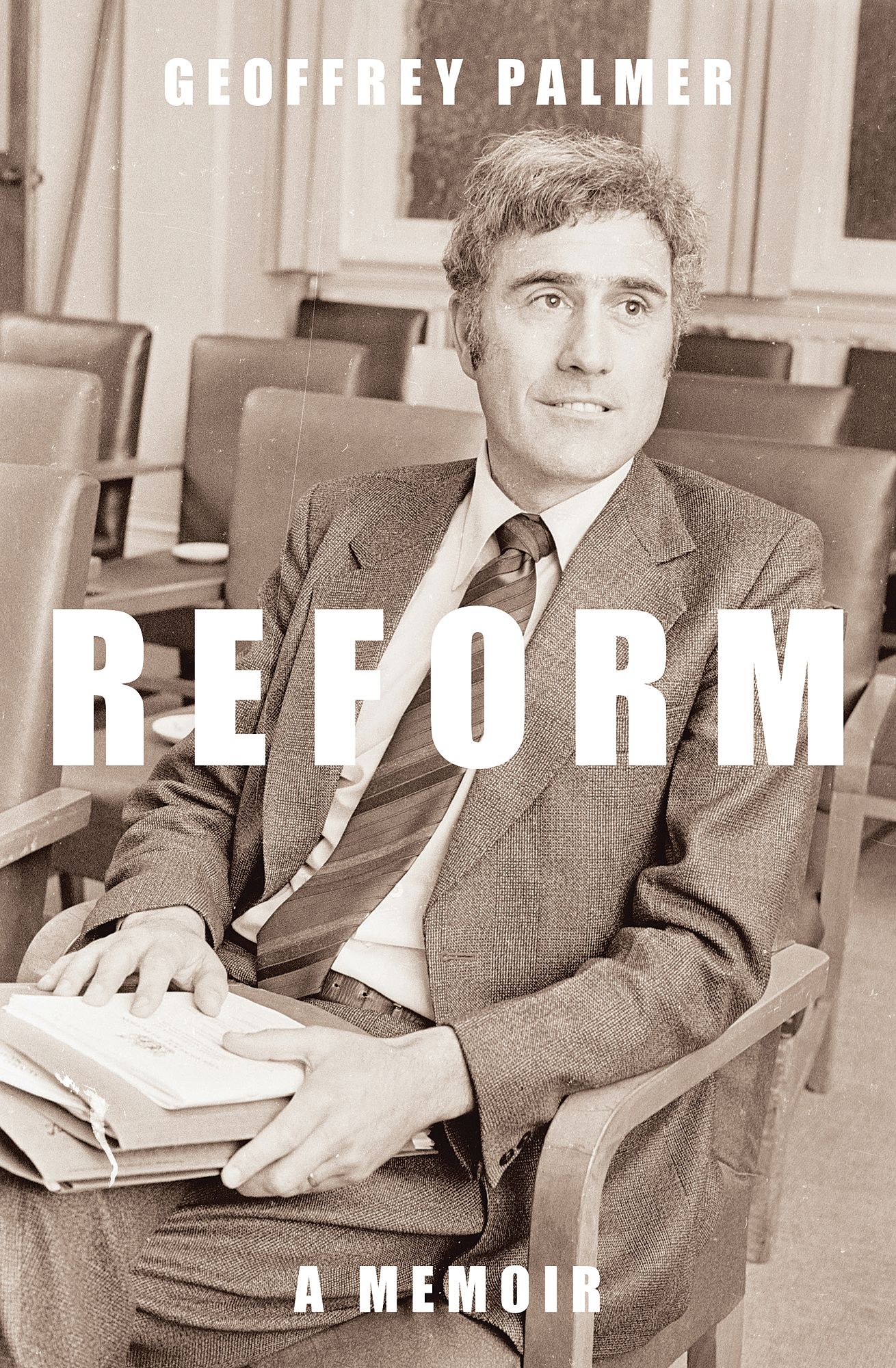

Everything Answered, Nothing Asked: Geoffrey Palmer's Reform and the Nature of Memoir

A 750-page memoir by the 33rd Prime Minister of NZ? Couldn't it be 850 pages? But reading Geoffrey Palmer's "Reform" begs some interesting questions about how - and for who - people compile a record of memories and encounters, as Di White discovers.

It was during a brief stint as editor of Victoria University’s Salient magazine that former Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer began publishing pin-up girls in a weekly feature known as ‘Girl of the Week’. It’s an unlikely skeleton in the closet for a man known best for his proper and reserved demeanour, his storied career as a politician, lawyer, legal academic and Law Commissioner. Is he regretful? Is he philosophical? What did the man then mean to the man now? “I certainly tried to liven the paper up”, he remarks somewhat dismissively.

It’s a controversial and fascinating insight into Palmer’s early political life, but it receives only a cursory mention in Palmer’s 750-page memoir Reform, especially compared to the lengthy and tedious detail with which Palmer covers other aspects of his life and career.

For anyone familiar with Palmer’s reputation, Reform feels like a missed opportunity. Palmer was often said to lack the charisma and personality that have become perquisites for successful politicians, instead being far better suited for the quiet and serious life of academia. Palmer himself seems well aware of the fact:

“…I was always careful and lawyer-like in my public utterances. That was a problem, since in modern politics it is necessary to be the sort of person voters would like to have a beer with. So my image was austere, remote and academic, especially compared with David Lange.”

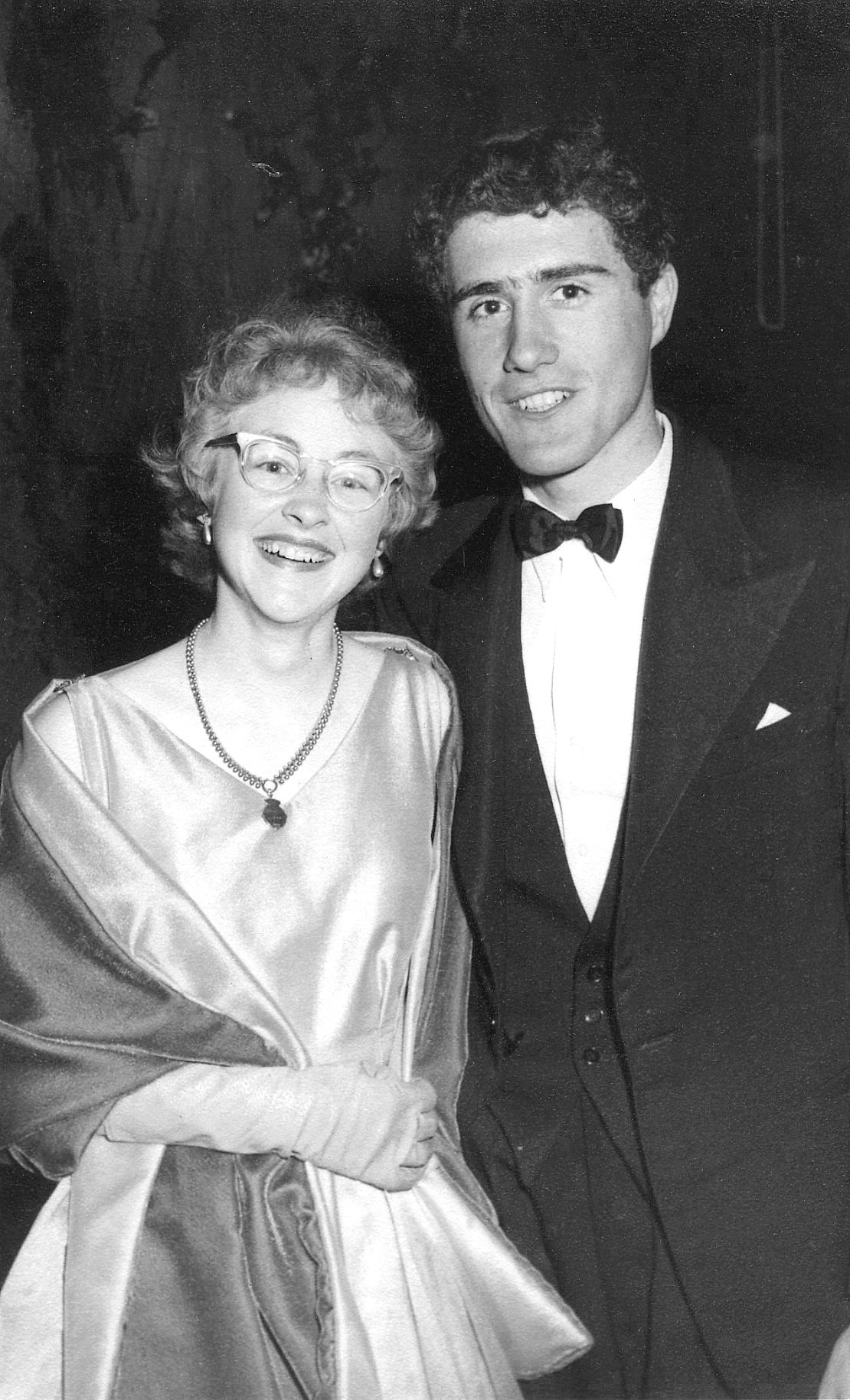

It’s an image Reform does little to debunk. Taken in its entirety (and for the casual reader, make no mistake – that’s a big ask), the memoir contains very little reflection of a personal nature. The death of his father, birth of his son and his marriage to Margaret Palmer all occur in the space of a paragraph, buried in the conclusion of a long chapter detailing his first role as a law clerk. Indeed, personal and humanising detail is actively shied away from: when discussing his determined and somewhat difficult nature as a child – especially during toilet training – he says the stories of such “are not to be gone into here”. Not only are stories like this an opportunity for Palmer to shake off the image of being austere and dry, but in opting not to do so Palmer reinforces this perception in favour of an incredible prissiness.

While perhaps a missed opportunity in some ways, Palmer provides many anecdotes for those with an interest in New Zealand’s political and legal landscape over the last forty years. His integral part in the creation of ACC, a world-leading scheme of no-fault accident compensation, is perhaps a lesser known of Palmer’s achievements, but an experience he describes as having made “an indelible impression on my whole outlook on the law, reform, politics and life”. His account of the process, the concessions made and the way in which the scheme has eroded over time – to the point it little resembles the original blueprint Sir Owen Woodhouse originally conceived back in 1967 – is an example of how Reform provides not only insights into a political past but can bring these to bear on the political present. Similarly, the detail of Palmer’s role in New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance, perhaps overshadowed in historical record by Lange’s Oxford speech, is a fresh and interesting perspective on a defining time for New Zealand’s national identity.

Yet Palmer’s treatment of the infamous 1980s Labour economic policy, led by Roger Douglas (who later split with Labour to form the ACT Party), is brief and somewhat defensive. Of the 750-pages, only five touch on the “New Right” economic policy of the Fourth Labour government of Palmer and his colleagues. The brevity with which these policies are covered fails to impart just how radical and divisive the policies were and remain. The way in which Palmer somewhat brushes over the period – he states “I do not want to go into a long analysis of the government’s economic policies”, instead outlining his “own approach” – shows the subjectivity of the genre, and makes the high-minded and scholarly tone of the previous hundreds of pages ring somewhat hollow. Reform presents itself as a historical record – comprehensive, well-researched and evidence-based – but ultimately it is just one man’s account.

*

There are glimmers of a person behind the image of a stately and serious man. He talks about having “ants in his pants for reform”, and how because of this Margaret, his wife who indeed gets mentioned often throughout the memoir and is clearly an important and much-loved part of Palmer’s life, calls him “Tigger”. Rather than an overall impression of Palmer being boring and devoid of personality, you cannot help but feel he is simply a deeply personal and serious man; socially awkward and lacking the spark of someone like Lange, but more than capable of emotionally connecting with people.

No doubt part of Palmer’s efforts to show his lighter side (not to be confused with the dreary final chapter, which, by way of epilogue, is entitled “Some Lighter Moments”), Reform contains a number of Palmer’s rather excruciating attempts at poetry. The poems are one of the most humorous aspects of Reform, although perhaps not for the reasons Palmer expected. Take, for example, “Animals”, a poem he slips in during a lengthy discussion about different cases in the common law concerned with animals (I kid you not).

Animals

I saw a woodchuck near the Burlington Street Bridge.

The students were looking at it

some not sure what it was.

Later the same day I saw a racoon.

They used to eat the tomatoes

I grew in Iowa City.

One the golf course I saw groundhogs.

Squirrels are everywhere here.

No New Zealander can see such animals at home.

We have deer, possums and rabbits

and so does Iowa.

Iowans think the last animals are cute.

We think they are vermin

to be wiped out.

It goes to show that everything is relative.

It is how you look at it.

Palmer ends his memoir with a story about taking the oath to become a Privy Councillor, the position that bestows the title Right Honourable on a person for life. “At the time I took the oath it was secret but it has since been made public. Reading it now I feel like a relic of a bygone age. Perhaps I am.” Somewhat devastatingly but presumably meant light-heartedly, those are his final words.

*

For Palmer, Reform appears to be an exercise of “getting it all out”: carefully and meticulously cataloguing an inventory of his life. He includes details that no person could possibly find interesting or important. He tells the story of the time he lost his watch in Tahiti on a stop-off when he was travelling to the US to study. He includes a two-page speech he gave in the speech competition at Nelson College. He footnotes the newspaper articles that confirms he did, indeed, win the Lieutenant Murray Fantham Memorial Prize in 1957 for best all-round boy in the fifth form (The Nelsonian, December 1958, Vol. LXXXIII, at 76, in case you’re interested). It’s an impressive feat of memory recall and personal genealogy, but for the reader, it’s exhausting.

Indeed, for someone who history might have perpetually underrated and misunderstood, this isn’t an accessible effort to set the record straight. His style is crisp and clear, as would be expected from someone adept in legal writing, but lacks almost entirely in flair. He quotes long passages from parliamentary reports, Law Commission documents, speeches, cases, and legislative acts. Many chapters include an introduction detailing what will be discussed and a conclusion on what was discussed, a hallmark of a lawyer. It begs the question: why devote 750 pages to something of very limited appeal to readers? It is clear Reform is not a book at which the reader is central. Palmer openly admits this: “What I want to do in this work is to make intelligible to myself, and perhaps to the others, the times I lived through and the things that seemed important to me.”

A memoir presents the writer the opportunity to cast the ever-elusive final word; the opportunity to paint their life in the most flattering light possible and let it stand is a pseudo-historical record. However, what represents you and your memories and achievements best to yourself may not be what represents you best to others (and therefore to history). For Palmer, a flattering light is cast by precision and perfection, whereas for most readers Palmer would have been be served by something more human and relatable.

In the end, what Reform does, presumably unintentionally, is raise questions about the memoir genre itself. There’s a certain degree of arrogance assumed in writing a memoir – more detail than an autobiography, less distance than a book the same size on anyone or anything else. At a crucial early moment, it’s something even Palmer seems to realise:

“There is a presumption involved in writing such a book that the author has something worthwhile to say in which other people will be interested. I am far from confident that this is the case.” While Palmer questions his own authority initially, the only answer he really gives is another 750-page book. The question of what makes one person’s life worthy of a memoir over that of another stays unanswered – a rare loose end left by an otherwise meticulous man.

Reform: A Memoir is available from Victoria University Press now.