C*ntry Calendar

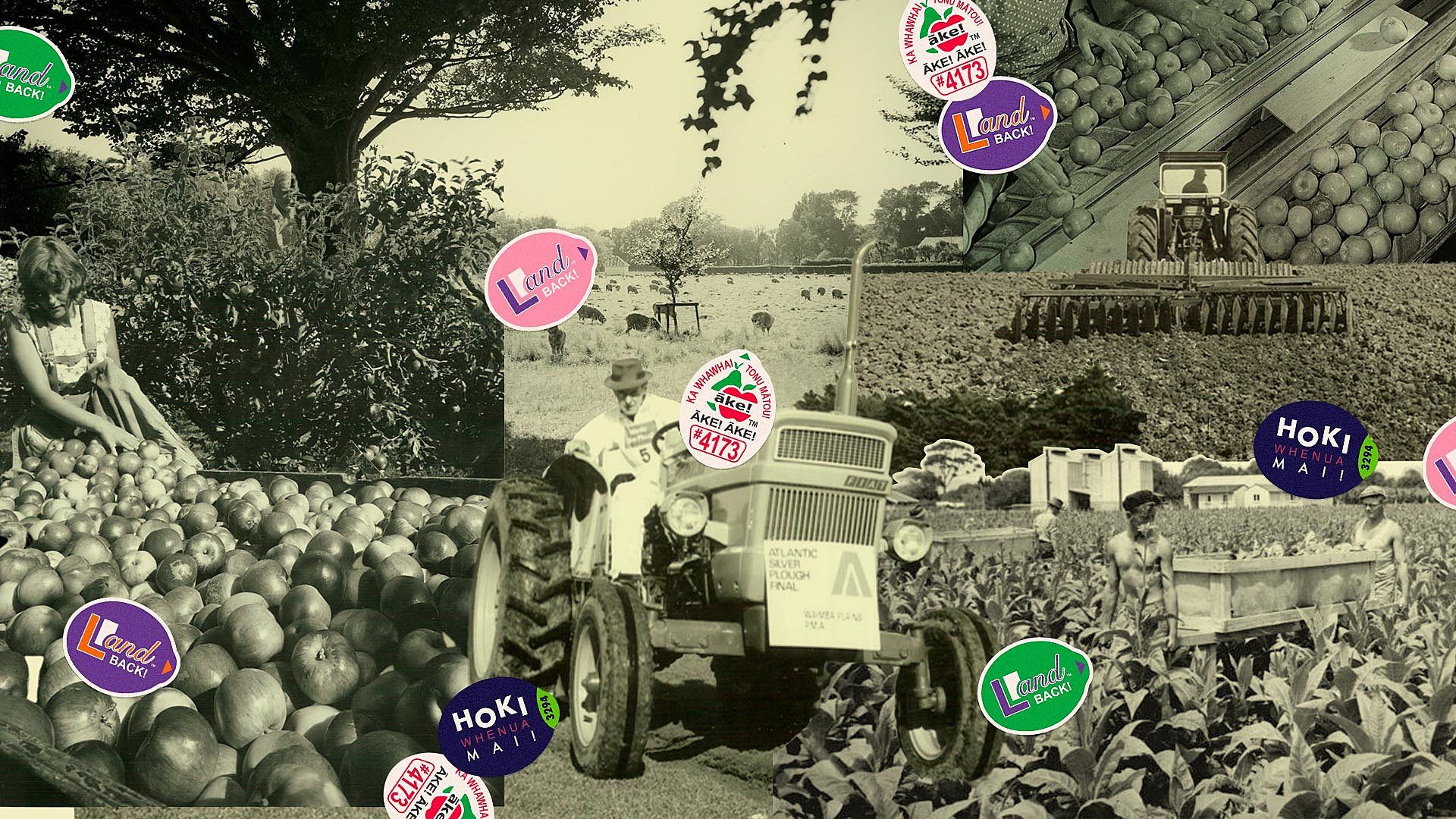

Country Calendar was one of Briar Pomana’s comfort television shows. She grapples with the realisation it romanticises colonial cottage-core lifestyle on what once was Indigenous land.

Country Calendar is a kiwi classic and one of our most popular local shows; a distinct Sunday ritual in many homes. Anyone who has watched even one episode across its multitude of seasons will know it is a reality show that follows the daily lives of farmers, agriculturalists, businesspeople and even fishers as they work the land and sometimes the sea. Mostly set in rural communities, the show captures the interest of fellow farming folk, and those that have cottage-core fantasies. Since the first episode in 1966, we’ve witnessed flowers blooming, lambs being mustered, horses galloping, oysters getting shucked, and Pākehā children skimming through orchard lines.

There is something to be said about a show boasting about whenua and moana ‘kaitiakitanga’ yet showcasing this almost exclusively through the generational wealth of non-Māori. I’ll admit Country Calendar used to be one of my comfort shows. I’d sit there with a cup of tea, something sweet to nibble on and happily hum along to the intro. I was a sucker for episodes specifically on some sort of sustainable practice they’d adapted or were working towards. Yet, after a year of TVNZ app usage for the sole purpose of watching Country Calendar, I found myself drifting further away from my weekend tradition. It wasn’t that the show can be quite repetitive and slow, it was the incessant ignorance and privilege of the farmers themselves.

There is something to be said about a show boasting about whenua and moana ‘kaitiakitanga’ yet showcasing this almost exclusively through the generational wealth of non-Māori

The messaging, whether intentional or not, was the same every episode. Either the Pākehā family was ‘gifted’ resources or land following World War 1 and then decided to raise their children there; or, my personal favourite, a tauiwi couple, usually from some distinctly white European country, came to Aotearoa on holiday and ‘just fell in love with the place’, bringing their old money here to set up shop. Both storylines are essentially the same, and are equally painful to watch. Country Calendar and the people featured rarely mention the iwi or hapū of their respective rohe.

I was reminded of this after one episode in which an older Pākehā couple smiled with glee at the success of their multi-million-dollar artisan citrus business. Not two minutes into the programme, I began to recognise the scenery and realised this limery was in Nūhaka, my papa kaīnga. I knew the brand and had seen their products displayed at farmers’ markets in Hawke’s Bay, but never knew they were nestled somewhere on my whenua. I finished the episode with my arms crossed over my chest and my brow furrowed.

The messaging, whether intentional or not, was the same every episode. Either the Pākehā family was ‘gifted’ resources or land following World War 1 and then decided to raise their children there; or, my personal favourite, a tauiwi couple, usually from some distinctly white European country, came to Aotearoa on holiday and ‘just fell in love with the place’

Featured on the show was their website. On it, the owners boasted about the “unique climate subtropical environment” where their limes are grown; even adding that with their drive and determination they have “created this once bare land block into a Wairoa landmark.” I wanted to cry, write letters, call my mum, and give their business a one-star review on Google, but what would any of that do? They were still going to be these Pākehā thriving off Rakaipaaka land, and I was still going to be a 20-something Māori barely getting by in a shared Mt Albert flat. This episode had me zoning out in the shower and asking myself, How in the hell did these Pākehā somehow take our whole existence and just run with it?

Country Calendar first aired on 6 March 1966. The episode depicted an apricot orchard in Central Otago, and the entire broadcast was 14 minutes long. Back then, the show was studio based, with frequent cuts back to the farm. After a new hot-shot producer by the name of Tony Benny took over, the show not only gained a new and improved theme song (which still stands today) but an increasingly ‘Kiwi’ feel. This revamp ditched the suits and ties of previous show presenters and took audiences right into the paddock, showing my fellow pavement-trotters the glitz and glamour of farm life.

How in the hell did these Pākehā somehow take our whole existence and just run with it?

In the 40th-anniversary episode of Country Calendar (2015), Tony Benny recalled an array of clips used on the show, shot before 1966. This older footage was set inside a shearing shed in 1937, on the Bull family farm in Canterbury. It showed a member of the Pākehā Bull family puffing on a pipe and watching as Māori shearers stripped layer after layer of thick winter wool from a seemingly never-ending flow of ewes. Benny distinguishes this as his favourite film piece to broadcast on Country Calendar. In his words, “It is reflective of New Zealand during that time.” To his credit, Benny is right; this piece of film depicts nothing other than colonialism.

Sitting by myself in 2022, watching the black-and-white clips, I couldn’t help but think of my papa. He was born on 27 May 1929, on our ancestral whenua in Nūhaka, a man of perfectionism and craftsmanship when it came to our land. When he was a teenager, he went out shearing, like most Kahungunu men of the time. My mum says that it was like watching a master carver at work when Papa sheared. The clippers in his right hand were like a well-loved chisel, and it was known to all that whatever my papa did, he needed to be the best at it. He had a style of shearing called a slow hand, where it looked like his blade was gliding across the fleece. Mum would imitate it, which reminded me of birds skimming across the water.

Sitting by myself, watching the black-and-white clips, I couldn’t help but think of my papa, born on 27 May 1929, on our ancestral whenua in Nūhaka

My papa just worked and worked and worked his entire life. A big man himself, he always had a big horse in tow. He knew the hills and families of Nūhaka like the back of his calloused hands and could build a damn good fence, too. It was the same for everyone else in our rohe, there were no other options than to throw your guts out in a field or in a shed, and my papa had no problem doing either. In fact, he thrived in these environments and, as he aged, dreaded the fact that he couldn't continue this mahi. He passed away in May 2017, a few days after his 88th birthday. As all our bodies do, his tūpāpaku returned to the people of Nūhaka and the clay of Rakaipaaka.

It is simply not enough for me to only be returned to my whenua when my body is buried in it. My whānau don’t have any kind of trust, or even very much in KiwiSaver, but, rest assured, we’re finding ways to make it back to who we once were and where we have always been. This is why my critique of Country Calendar is so personal. Country Calendar and the predominantly Pākehā men portrayed week in and week out for the last 56 years are physical manifestations of ongoing colonial violence enacted on our whenua and against our whānau whānui.

Land back, water back, sex back, dreams back. We want it all

It is not only a glorification of the imperial tradition that Country Calendar seems to hold on to so dearly. It is a romanticisation of lifestyles that in the past were always Māori. To watch your whakapapa put on like a costume and flounced by Pākehā farmers pretending to be kaitiaki feels apocalyptic, and enough is enough. This racist justification of colonial violence is getting rather old and worn out. Pākehā mā, all that money you feel assured by, and the truth you continue to ignore about who you are and how you got here, still does not erase whakapapa Māori. Our connection to these lands will always enable us to return to them. Without your fancy papers and zeros on a screen can you say the same?

Land back, water back, sex back, dreams back. We want it all, so I’d hold on tight to that piece of paradise you think you own outright. Time is liminal, and we are all entering a renaissance. Your wealth and your access can no longer keep what is us from us.

Hoki whenua mai!

Feature image: Nuanzhi Zheng