Chainsaw Woman vs The Eye Devil

In the final essay response to AMF’s Niu Gold Mountain video project, Alex Stronach dissects Che Ebrahim’s Body Shop – in all its body-gore, trans-vengeance, horror-splat glory.

All My Friends are a creative collective from Tāmaki Makaurau who dream up and create events for our Queer and PoC whānau. Niu Gold Mountain is a four-part collaborative video project with 13 emerging Asian and Pasifika creatives, which asks “What is your New Gold Mountain?” What are your aspirations? The search for a better life is a story that defines the migrant diaspora.

In partnership with All My Friends, we have invited four writers to reflect on the themes, journeys and stories explored in the videos. In this essay, Alex Stronach responds to Body Shop, by Auto Angel (Che Ebrahim), Casey Yeoh, Hailee Tamore.

Read the whole series here, and find out more about All My Friends here.

Ophelia is gravid with eyes. They nest beneath her skin, inside her flesh. Others stare at her from every screen in her workshop. She cuts into herself and carves them out and welds metal in their place, a sort of makeshift armour. Her cis friend is disgusted – You used to be so cute. Ophelia kills her with a chainsaw and all I can really do is mutter girl, same.

This is Body Shop, a short film directed by Che Ebrahim, filmed and edited by Casey Yeoh, with makeup and SFX by Hailee Tamore, which was made in collaboration with All My Friends as part of their project Niu Gold Mountain, consisting ofMango, Mahiwaga, Movin’ and (of course), Body Shop. The other three gold mountains are dance and song, sharp and gentle and strange and beautiful, but only Body Shop has a chainsaw. I’m not sure how to explain it to the cis, but we must try.

To be a trans woman is to be subject to constant scrutiny, to never escape notice, to carry the weight of constant judgement; the eyes are fucking exhausting.

Today on the bus a woman wouldn’t stop staring at me. She didn’t seem scary, or even malicious. She seemed, more than anything, equal parts curious and supportive. It didn’t stop her gaze making me feel small and trapped, as though my trans femininity made me some sort of zoo exhibit. To be a trans woman is to be subject to constant scrutiny, to never escape notice, to carry the weight of constant judgement; the eyes are fucking exhausting. Sometimes I feel like the eyes are inside me. Everybody stares at me so much that I can’t help but stare at myself constantly and worry myself sick as to whether I’m doing trans correctly. What I would give for Ophelia’s strength, to tear out the eyes and build my body anew.

All the trans folks reading will roll their eyes but I’m sure there’s a few cis in the audience who’ve never heard the old chestnut: the curse of trans men is invisibility, the curse of trans women is hypervisibility. As soon as I grew tits I stopped being able to go outside without being stared at. I would give anything to give them a fuck you stare back, but that’s how a girl gets hate-crimed. When I came out to my mum we were in a restaurant, and part way through the conversation she said, “That woman is looking at you, should I talk to her?” Bless you, Mum, that’s sweet, and more trouble than it’s worth. Ophelia, played by Jordan Sio-Milne, does what I can’t, and stands up for herself. Her reconstruction takes the form of a magical-girl transformation sequence, lovingly animated in a classic 90s anime style, halfway between Sailor Moon and Ghost in the Shell. Ebrahim cites GitS, Akira and Tetsuo II: Body Hammer as inspirations.

“Those movies and TV shows feel very trans to me, but a lot of the transformative events are being inflicted upon someone, out of their control, so I wanted to flip that, and make it more obviously trans.”

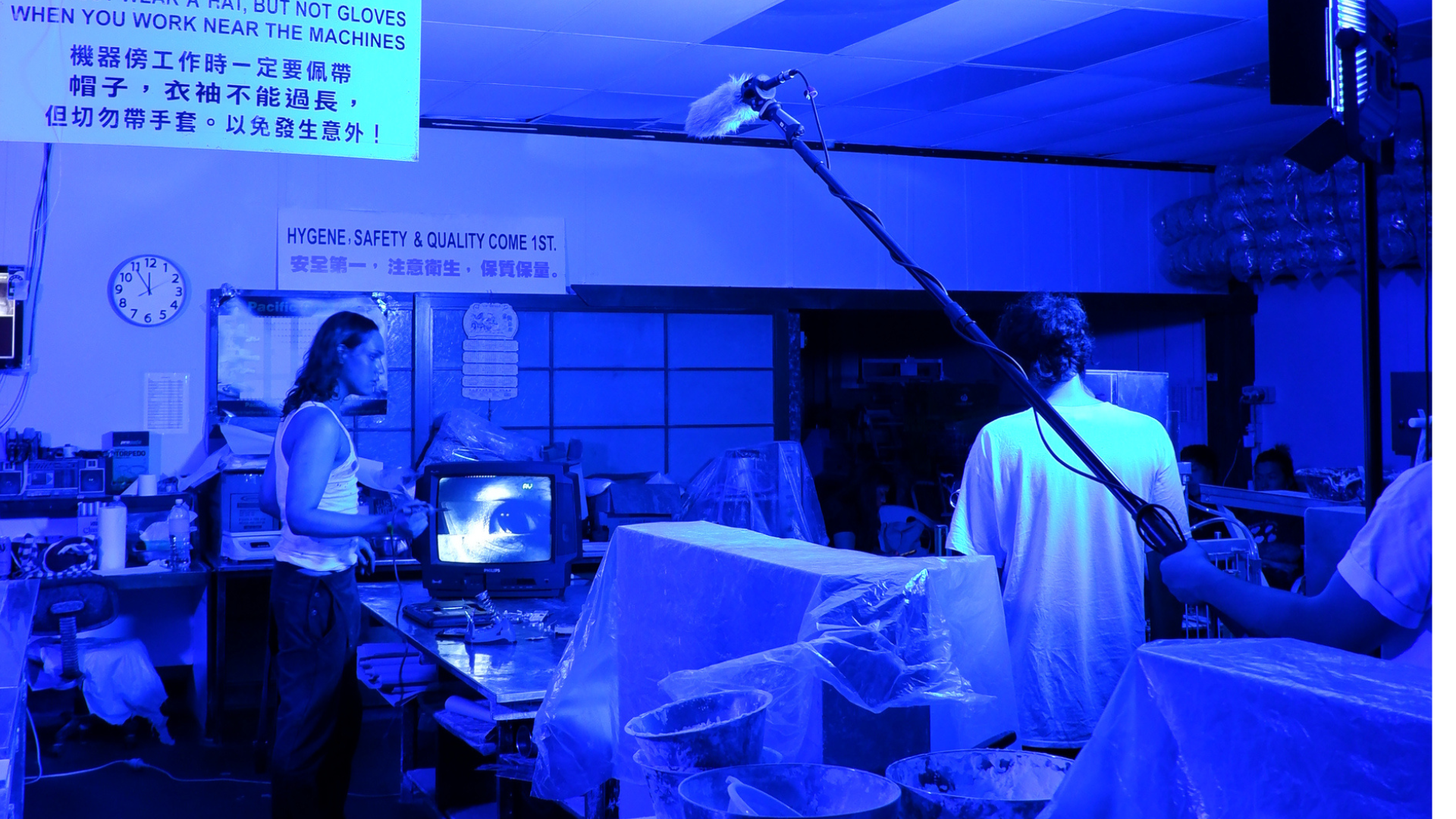

Image courtesy of All My Friends

It’s impossible to speak for every trans woman on the planet, but it’s hard to miss that body horror and cybernetic enhancement are two recurring elements of a lot of trans works. I brought that up with another doll, a horror author, and she screwed up her face and said, “It’s not horror.” Watching Ophelia cut open her arm and tear out the eyes clustered inside her like a clutch of horrible eggs, it’s hard not to be shocked –

and yet –

it’s liberatory. When I asked Ebrahim about it, they called them ‘enhancements’. I like that.

“Because we take the limitations that were imposed upon us (whether that be societal or physical) and breach them. I, as a trans woman, had to kind of mentally deconstruct myself and rebuild myself, so the metaphor of DIY cyborg enhancements feels like a natural extrapolation of that.”

Body Shop is deeply concerned with the nexus of racism and transphobia, and how New Zealand’s violent colonial history echoes through our modern Queer spaces.

It’s hard to miss that Ophelia is a woman of colour and her mate-with-opinions-about-cuteness is Pākehā – Body Shop is deeply concerned with the nexus of racism and transphobia, and how New Zealand’s violent colonial history echoes through our modern Queer spaces.

A key part of colonialism is the subjugation and dehumanisation of people who don’t fit into this (cis, white, etc.) ideal, explains Ebrahim. “This homogenisation of culture and the way people are allowed to be manifests in so many ways, including respectability politics, politeness, beauty ideals, cultural appropriation; and to more dire things, like genocide, and cultural eradication,” they add.

This includes the homogenous idea of Queerness, which continues to be defined by (mostly cis) white people, who have the most incentive to appeal to colonialist and capitalist ideas, in hopes it may give them a seat at the table. “[They] have the most privilege and are the most palatable to the general public … it is a consumable version of Queerness. It gets adopted by capitalism, not through change, but by design. Like the commodification of Pride flags.”

Image courtesy of All My Friends

For Ophelia, the act of cutting off her hand renders her unable to do her job and participate in capitalism, says Ebrahim. “She is replacing her hand with a tool, one that more aligns with her goals (shout out to Audre Lorde). Which in this case is a chainsaw for killing people who are shitty to her, which is just a silly way to visualise that metaphor.”

Body Shop’s industrial-warehouse vibe is thanks to producer Kevin Shen’s uncle’s noodle factory Chan Kee, based in Ōtāhuhu, a family business that’s been supplying pastry and noodles to local Tāmaki Makaurau restaurants since the 1980s. This serves as a thread to the other three videos in Niu Gold Mountain,which are all set in retail, food and restaurant establishments vital to BIPOC communities in Tāmaki Makaurau. The cold lighting and the workshop mise-en-scene come together to make it feel claustrophobic – cramped, cyberpunky 80s industrial energy that permeates so much trans art. It’s not scary to us, “it’s not horror”, our worlds have already ended, we’re in the process of building new ones, starting with ourselves.

It’s not scary to us, “it’s not horror”, our worlds have already ended, we’re in the process of building new ones, starting with ourselves.

The film definitely has a kind of over-the-top Evil Dead splatter-film vibe to it, yet it feels anything but silly. It’s fucking cool. It’s liberation. It’s a righteous war against the hateful gaze that trans women, and particularly trans women of colour, face every day. It is exhausting rebuilding your body, turning it into a tool, a weapon, a temple, and every day we go out and our friends stare and say passive-aggressive bullshit, and they’re our friends. Ophelia is the girl who does what I wish I could. I can’t help but stare, admire, watch her rebuild herself over and over again.

Like, girl, same.

Image courtesy of All My Friends

Body Shop was produced by Abbey Gamit, Kevin Shen, Tyrun Posimani and Tommy Jiang.

Additional credits to Auto Angel, Hailee Tamore and Casey Yeoh. Body Shop was showcased as part of Niu Gold Mountain, Studio One Toi Tū, 6 April – 4 May 2023.

Watch the video below: