Ray Leslie is Creating Her Own Shot

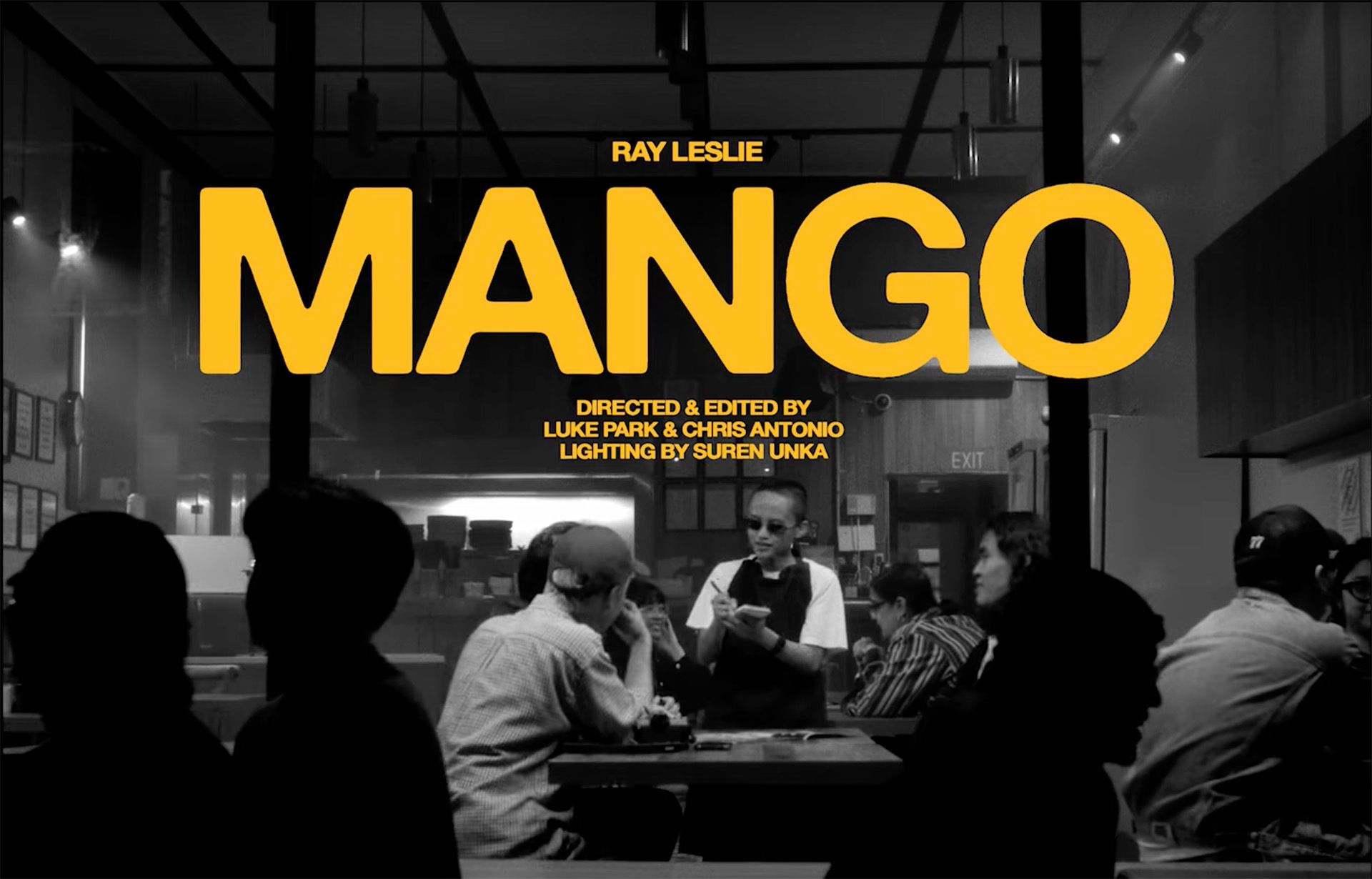

In partnership with All My Friends, we have invited four writers to reflect on the themes, locations and stories explored in the video series Niu Gold Mountain. Han Li responds to the music video Mango, by Ray Leslie, Chris Antonio, Luke Park and Suren Unka, set in Selera restaurant.

All My Friends are a creative collective from Tāmaki Makaurau who dream up and create events for our Queer and PoC whānau. Niu Gold Mountain is a four-part collaborative video project with 13 emerging Asian and Pasifika creatives, which asks “What is your New Gold Mountain?” The search for a better life is a story that commonly defines the migrant diaspora in Aotearoa.

In partnership with All My Friends, we have invited four writers to reflect on the themes, journeys and stories explored in these videos. In this essay, Han Li responds to the music video Mango, by Ray Leslie, Chris Antonio, Luke Park and Suren Unka, set in Selera restaurant.

Read the whole series here, and find out more about All My Friends here.

It was near the end of the show that Ray Leslie decided to drop out of university. She was watching Brockhampton as they chanted “I want more out of life than this”, the outro to their song ‘San Marcos’. “I was like, facts,” she remembers. “I made the decision to drop out of uni the next day.” While this sounds dramatic, the decision was actually an easy one for Ray. She felt aimless while at university, studying for a degree that didn’t interest her and uninspired by the slog of student life. She was already spending most of her time making music. Dropping out would allow her to focus on it fully. “It wasn’t really a decision, but a necessity,” she adds, matter of fact.

Music has been an important part of her life since she was young. Her dad was an amateur guitarist and avid collector of classic rock albums, which he would play around the house. As her own tastes developed in her teen years, she gravitated towards hip-hop. Going through what she calls her “angsty teenager” phase, she was drawn to the raw honesty of artists like Eminem and J. Cole, and the genre’s lyrical focus resonated with her. She started to make her own songs, rapping over loops of her guitar playing and uploading them onto the internet.

Behind the Scenes of Ray Leslie in Mango

These home recordings were raw and unformed, often without any drums and released to an audience of her close friends only. But she loved the process of creating and kept going. By the time she was at university, almost all of her spare hours were spent making music. She estimates she has released about 12 fully fleshed projects since the age of 16, though most have been scrubbed from the internet. Ray is much happier now than she was during her time at university, but she does note that there is an irony in her choice to drop out: “It’s funny, my parents moved here for better education, and like, I dropped out of university to be a musician.”

Like her dad used to, Ray spends her weekdays working for an American fast food chain. She’s an assistant manager at Krispy Kreme, where she has worked since dropping out. It’s a job that is familiar to her family. When they first immigrated to New Zealand from the Philippines, her dad’s experience in medical sales meant nothing to local employers. Struggling to find a job, he made ends meet by working at McDonald’s. Her parents have since climbed their way to financial stability, but Ray still remembers the relentless work that it took to achieve that.

“It’s funny, my parents moved here for better education, and like, I dropped out of university to be a musician.”

It is this work ethic ingrained in Ray that has allowed her to carve out a shot at a career in music. Her early recordings were released without any promotion and predictably did not get picked up (she describes her knowledge of the industry at this stage as “deluded”). This made her realise she needed to work harder and smarter. She polished her sound, using her savings to record at studios and have her songs mastered. She learnt about promotion and got her music onto streaming services. And she started to “DM everybody”, scrolling through Instagram and reaching out to anyone that she admired. These DMs helped her find friends in the arts community of Tāmaki Makaurau. They also linked her with All My Friends, who asked her to contribute a piece to their Niu Gold Mountain exhibition.

Filming Mango in Selera

Mango is Ray’s contribution to the exhibition. It is almost a love letter to her parents: a tribute to the sacrifices they made to allow her the opportunities to chase her own dreams. More than this - it’s about the precarity of migrant life and how daring the decision to move to Aotearoa was. Ray imagines what it felt like to make that decision: “They envisioned gaining freedom when the sight was weak / Then we were flying like we didn’t have a fear of heights”. The key phrase here is “like we didn't”. She knows her parents were probably scared of the risks, but they did it anyway.

During the refrain, Ray parallels her own dreams with her parents’ achievement, singing: “I’m trying to make something as big as you.” But she can’t quite articulate what could be “as big”. For the next few lines, the words stop at the tip of her tongue. To me, her stuttering delivery here feels like the difficult-to-express appreciation many children of immigrants have for their parents. That sense of awe at their achievements, which you feel like you can never really match.

For the Mango video, directors Luke Park and Chris Antonio put Ray in an Asian restaurant. For many in the Asian diaspora, the restaurant is not just a place for them to connect with their culture, but also a crucial way to earn an income. Experience and qualifications gained overseas often don’t count in the mainstream job market. Operating a restaurant is one of the few ways for immigrants to have control over their destiny. Restaurants are also symbols of entrepreneurial ingenuity. Selera, where the video is filmed, is a Newmarket institution. It has drawn customers for years by carefully adapting its food towards the tastes of the day.

Operating a restaurant is one of the few ways for immigrants to have control over their destiny. Restaurants are also symbols of entrepreneurial ingenuity. Selera, where the video is filmed, is a Newmarket institution.

The video alternates between shots of Ray serving food at Selera (“It’s what I do in real life anyway”) and performing on the tables of the same restaurant. The performance scenes are smoky: Ray flits in and out of darkness without any acknowledgement from the customers. The lighting – designed by Suren Unka – flickers to create a surreal atmosphere, as if the performances are happening in Ray’s imagination – a daydream of what she wishes she was doing. Watching these scenes makes me think of all the immigrants whose own dreams are ground down by the need to survive. Who in another life may have been actors or musicians instead of service workers. This bitter-sweetness stuck with me after watching the video. For some immigrants, the performances in their own minds are the closest they will get to their dreams.

Filming Selera

I found myself reflecting on the journey of my own parents while watching Mango. They immigrated to Aotearoa in the 90s with two suitcases and no connections. While my dad never had to wait tables, his first job was cleaning the toilets at Westfield Manukau – a stark contrast to the engineering job he had worked so hard to get in China. Growing up, I vividly remembered how hard my parents worked and how careful they were with money. Through that hard work and some good fortune, they live in suburban comfort now. But hearing stories of their early years, I think about how they must have felt when they first touched down. I wonder if they were also scared.

It’s invigorating to hear these immigrant themes in Mango, especially in the context of it being a hip-hop song. The language of immigrant hustle is not a traditional interpretation of the genre, but, to my mind, it’s an appropriate fit. Because more than any other genre, hip-hop contains a core of unapologetic ambition. It was created by adapting other people’s music with the goal of drawing crowds. Its biggest stars often come from poverty, and make songs that celebrate the disorientating joy of self-made wealth.

It sounds like a new iteration of hip-hop, one that fuses the ambition inherent in the genre with the context of the immigrant hustle.

During university, this unapologetic core drew me to hip-hop. It felt good to try and locate myself within its hustle and grind. It allowed me to trick myself into believing my everyday life was more dramatic than it was. That there was a parallel between me getting up early for my lecture and their rhymes about selling drugs on the street for survival. At the time, I brushed past the stark contrast of my middle-class suburban life, which makes this slightly embarrassing to look back on now. I like that listening to Mango provokes those same feelings, but with less embarrassment. This time, the analogy feels much more appropriate, as I too saw the type of struggle that Ray’s parents went through. It sounds like a new iteration of hip-hop, one that fuses the ambition inherent in the genre with the context of the immigrant hustle.

Ray lives that hustle every day. It’s been five years since she left university. She admits that sometimes she feels insecure as she sees her friends advance their careers, especially now that she knows the scale of the challenge. As she says, “It feels so much bigger now that I’m closer to the painting.” When this happens, though, she likes to channel the delusional side of her teenage self. “It’s gonna get so much harder the more successful I get. I know I’m gonna get there, so I’ll just enjoy it while it’s not here.”

Mango was showcased as part of Niu Gold Mountain, Studio One Toi Tū, 6 April – 4 May 2023.

Watch the video below:

This series of essays with All My Friends was made possible through support from the Ethnic Communities Development Fund.