Afghanistan, being like a garden

Ilham Akhlaqi asks when her home country will ever get the chance to blossom.

Afghanistan has always been a blur in my vision. My family fled to Iran in 1982, during the Afghan–Soviet war, which lasted nine years and displaced 2.6 million Afghans. Since then, my family and I have been refugees of war for over two decades, living in three countries. We came to New Zealand as refugees in 2005, learning a new language and starting life all over again, which clearly didn’t make me ‘fit’ into society. I’m still adjusting to an ethnic limbo. It’s hard to talk about war when your presence here is the result of it and you are no longer experiencing it first-hand. Growing up, being raised away from home (Afghanistan) in two completely different countries, I often felt disconnected from my roots. My mother was also a refugee at two, so neither of us was raised in Afghanistan. My Afghan heritage was already fading away as it was. With the Taliban overtaking Afghanistan, the recent activities happening there have disheartened me immensely – I am, after all, an Afghan.

I was born in Iran in 1999 to refugee parents, and I was not completely ‘accepted’ there either. My birth country wouldn’t even provide me with a birth certificate, stripping me of my rights and privileges as a citizen. With no documents, you were not allowed to access government services such as schools or universities, open a bank account, or work in a civil or well-paying job. In order to live a comfortable life as a refugee in Iran, you either worked in trade or as an undercover, low-paid worker. As a child, you don’t understand the connotations that come with being a refugee. You have fun playing around, and that’s all you know – you don’t outgrow the shell you were born into. When you pick up the pieces, you begin to realise that you don’t have the same advantages as those around you. Children my age attended schools and were given the privilege of legal documents and civil rights that I wasn’t.

I played in the beautiful gardens and visited scenic sites such as the Blue Mosque in Mazar-e Sharif

In Iran, you start school at the age of seven. My sister, who is two years older than me, wasn’t allowed to enter school because she didn't have an identification document. My mother herself was stripped away from her own opportunity to access education. She didn’t have the documents either, but she was also the oldest and cared for her siblings, and her family couldn't afford to send her off to school. She knew the influence of education and how it could change one’s life. She wanted a better opportunity for her daughters. I vividly remember her frequent trips to schools, hoping that just one would give my sister an opportunity for education. This was now the lives of millions of Afghan refugees. Starting a new life in another country traumatised and with no wealth is already difficult. But knowing that your children will not excel from the life they were born into is yet another obstacle.

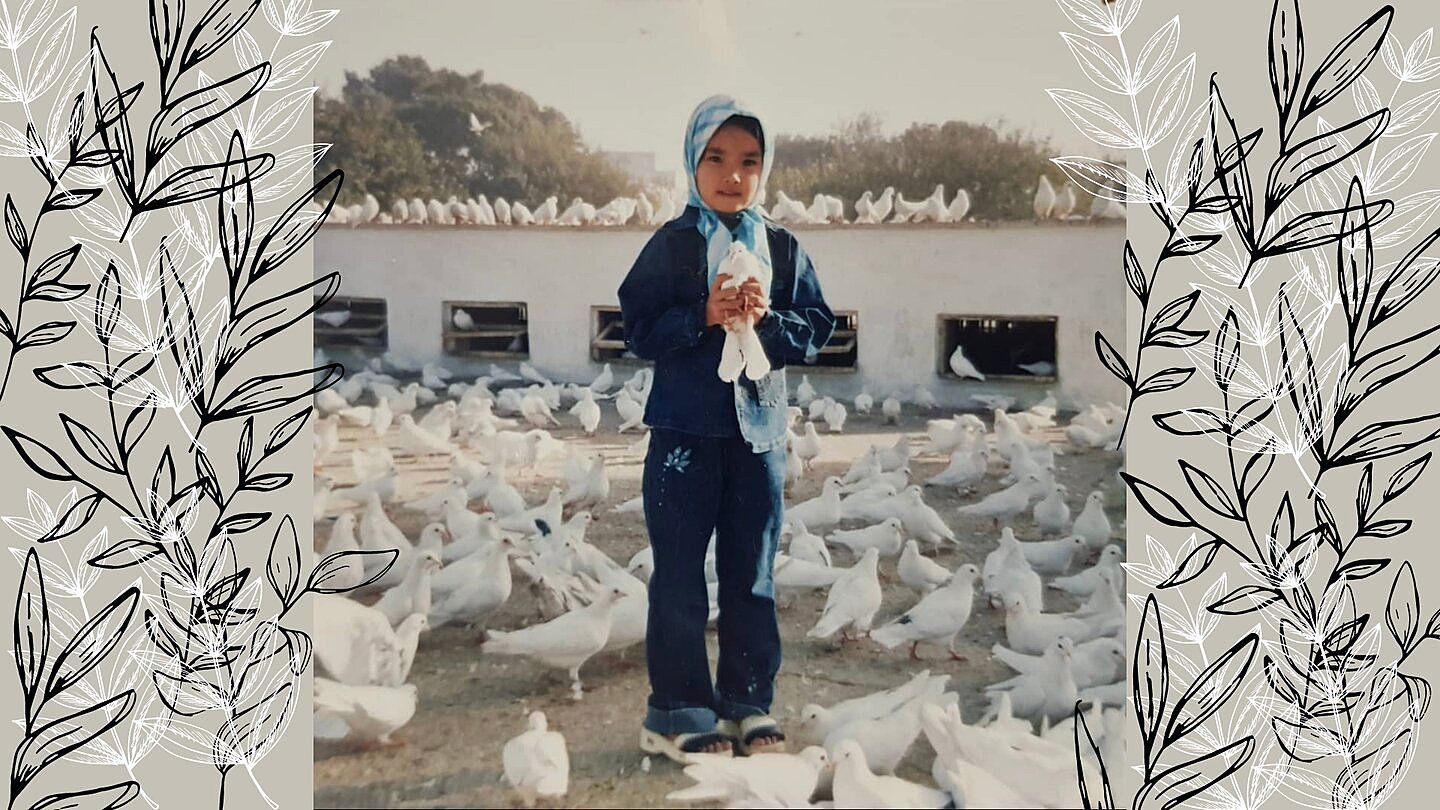

When I was six, we travelled back to Afghanistan. Although the Taliban were no longer in power in 2005, they still ruled over rural areas and occasionally examined passengers in cars on main roads. My short stay in Afghanistan was sweet to say the least, I met wonderful families, played in the beautiful gardens full of roses, visited scenic sites such as the Blue Mosque in Mazar-e Sharif – finally experienced living in Afghanistan. I never wore the hijab in Iran as I was younger than the mandated age, but mum made me wear it in Afghanistan. She, too, started wearing the chador (a black cloak covering your entire body except for your face). These were the extra precautions taken. The fact that my innocent six-year-old body was covered by a hijab exhibits the extremist ideologies and hold the Taliban has over women and young girls.

I never felt safe in Afghanistan, even as a child because of the Taliban

At the age of five, I remember second-handedly watching countless movies about the Taliban with my family. Although I don’t remember the storyline, I’ve memorised a scene where a member of the Taliban hides under the burka, a blue covering worn by women in Afghanistan, which covers the entire body, including the face. These members would kidnap young children from the streets, hiding them in the long, blue fabric. So when I saw women in the streets of Afghanistan wearing burkas, I would fear them, thinking they were all members of the Taliban. It is a misconception to think that under every burka, there is a Taliban spy. Looking back, the innocent women wearing the burkas are the people I should have feared the least. I never felt safe in Afghanistan, even as a child because of the Taliban. It was home and the Taliban made it into a prison.

The popularity of the burka rose when the Taliban started overtaking Afghanistan in the early 2000s, and wearing the burka was made compulsory for women. There were other laws as well: women weren’t allowed to leave home alone; if they left, they were required to have a male companion (a blood relative or husband). Any photos showing women or women speaking were not allowed in any form of media (newspapers, books, shop-fronts, radios, films, etc.). Women were also forbidden to appear on the balconies of their apartments or houses. Girls as young as 12 were taken from families to be ‘wedded’ to Taliban soldiers. Basically, women should be invisible, not allowed to be heard, seen or felt. With the current rule of the Taliban, these laws are being enforced again in 2021.

“The face of a woman is a source of corruption”

As a member of the Taliban states, “The face of a woman is a source of corruption”. The Taliban have enforced the burka on women, a construct of their own radical thinking. Those who don’t abide by the law are met with extreme consequences, including death. The hijab in Islam, on the other hand, is intended to be a choice, a right, freedom, and the person wearing the hijab must be willing to wear it.

Islam comes from the Arabic word ‘sal’m’, which literally means peace, and the Taliban are opposite to what Islam is. They have bought terror, murder, gloom into the country. The members of the Taliban have killed thousands of people and terrorised millions, which contradicts what Islam teaches us. In the Quran, it states, “Whoever kills a human being without [any reason like] manslaughter, or corruption on earth, it is as though he had killed all mankind ....” (Quran, Surah 5: Verse 32). People fail to realise that the Taliban do not represent Islam, the way the KKK don’t represent Christianity. The Taliban are people who have been brainwashed into thinking that what they’re doing is good, the way the KKK are also brainwashed into terrorism.

Afghanistan and Afghans are not pawns in someone else’s game

I have seen so many videos on social media, including a woman in Pakistan advocating for being pro-Taliban. Still, when asked, “Would you want the Taliban to rule Pakistan?” she became hesitant and quickly said, “No.” That is the world we live in, everyone advocating for things they cannot comprehend. Afghanistan and Afghans are not pawns in someone else’s game.

I could sit here all day writing about the history and events in Afghanistan over the past few decades. It wouldn’t be enough to touch on all bases of history – including the corrupting influence other countries have had on Afghanistan. Afghanistan is a land rich with minerals, oils, metals and resources. It is one of the last countries in which oils are untouched by mankind. It has one of the best geographical locations, centred in the middle of Asia. It is no surprise that many will fight to have it, but it is causing millions of people to suffer.

War eliminates the physical safety of people, but there are also psychological consequences. The after-effects of war have left not only my family but also millions of others with intergenerational trauma. Children of former refugee families experience challenges that would not exist if there had been no war. Many mental-health conditions go unnoticed due to Afghans’ coping strategies, such as religious and spiritual practices. They will take measures such as black magic and reading verses of the Quran to ‘cure’ their mental-health issues. Mental-health research on the war in Afghanistan shows that it has led to symptoms of depression in 67.7 percent of people, anxiety in 72.2 percent, and post-traumatic stress disorder in 42 percent. Many of these people don’t get the right type of treatment, resulting in intergenerational trauma. I have seen this in refugee youth in Aotearoa, battling cultural, religious and intergenerational trauma issues.

Afghanistan is bleeding, and the world just watches

I’m not going to lie – I used to deny that Afghanistan was my home country. I was so different from the people, and my family was raised in a whole different country. Even at the age of six, I was afraid of that country. But growing up, the more I understand what has happened to the beautiful country, the more I feel connected to my roots. I never got to know home since the war began, and I hope one day it will become the safe country it once was.

Even though we have left Afghanistan and Iran, we have brought a part of our home to Aotearoa. Home for me will be in the middle of the three places, and I’m not alone – I’m one of the millions of Afghan refugees displaced somewhere in the world. With the recent news of the US retreating their troops and the Taliban taking over the country, I fear more people will become displaced. History is repeating itself – the cycle is happening once again. Afghanistan is bleeding, and the world just watches.

Too many lives.

Too many lost lives.

How many more do we have to lose for humanity to take its stand?

Afghanistan, being like a garden.

With delicate, harmless, beautiful people.

Are being torn. Mercilessly killed. Displaced. By the vicious Taliban.

Like a garden, it requires a lot of flowers.

What is a garden with no flowers? What’s a garden with no buds?

Now, it’s just thorns ruining the very fundamental roots of the country.

Our generation of refugees in New Zealand – we have the joy to witness the beauty and growth of our loved ones here in Aotearoa.

We are a community with gardens filled with every diverse flower we can think of. Safe. Untouched. Innocent.

We watch violent movies, play war games, we control the trauma we consume through social media and the internet.

Click here, we buy ourselves the most extravagant of things

Click here, we take photos of our most extravagant of dresses

Click here, we watch the latest violent TV shows

Oh but Afghanistan

Back home where our ancestors lay in the mountains

Back home, where our parents played in the sandpits

Back home when home is supposed to be the safest of all places

Afghanistan

But now kids our age wait.

Now, girls and boys our ages don’t have many choices.

Sit here, they hear an explosion.

Do that, they get a bullet across their head.

Stay awake – as no night is safe, sleeping is not an option.

A baby as young as one, doesn’t even have the right to live.

Pregnant mothers carrying the next generation

Are lying dead on battlefields with grief on their faces

Afghanistan handcuffed in blood.

Once again, when will our country ever-so-blossom?

What crime have we committed?

Former refugees here today are the very reminders and consequences of war.

We are the eyes for the oppressed.

We are the mouths of the voiceless,

We are the hands for the helpless,

We are the feet for the prisoners of war,

So take this time to spread awareness.

We need to change the history that’s repeating itself.