Whakanuia: Best Aotearoa Reads 2018

Literature Editor Hannah Newport-Watson and recent contributing writers from the Pantograph Punch’s books section share their favourite Aotearoa books of the year.

There are more books in the world than there were a year ago. The reading pile beside the bed grows ever taller. Christmas means different things to different people – to me, it means I can finally lie down in the shade and read for hours on end.

In 2018 we were blessed by some incredible literary visitors to Aotearoa: Jenny Zhang, Sharlene Teo, Harry Josephine Giles, Hollie McNish, Patricia Lockwood, Raymond Antrobus, to name just a few outstanding highlights. I am grateful for the incisive festival programmers and producers who bring us these stars. But it’s also been a year of incredible local talent, too, which is what we are celebrating right here, with this selection of our favourite Aotearoa books we read during the year.

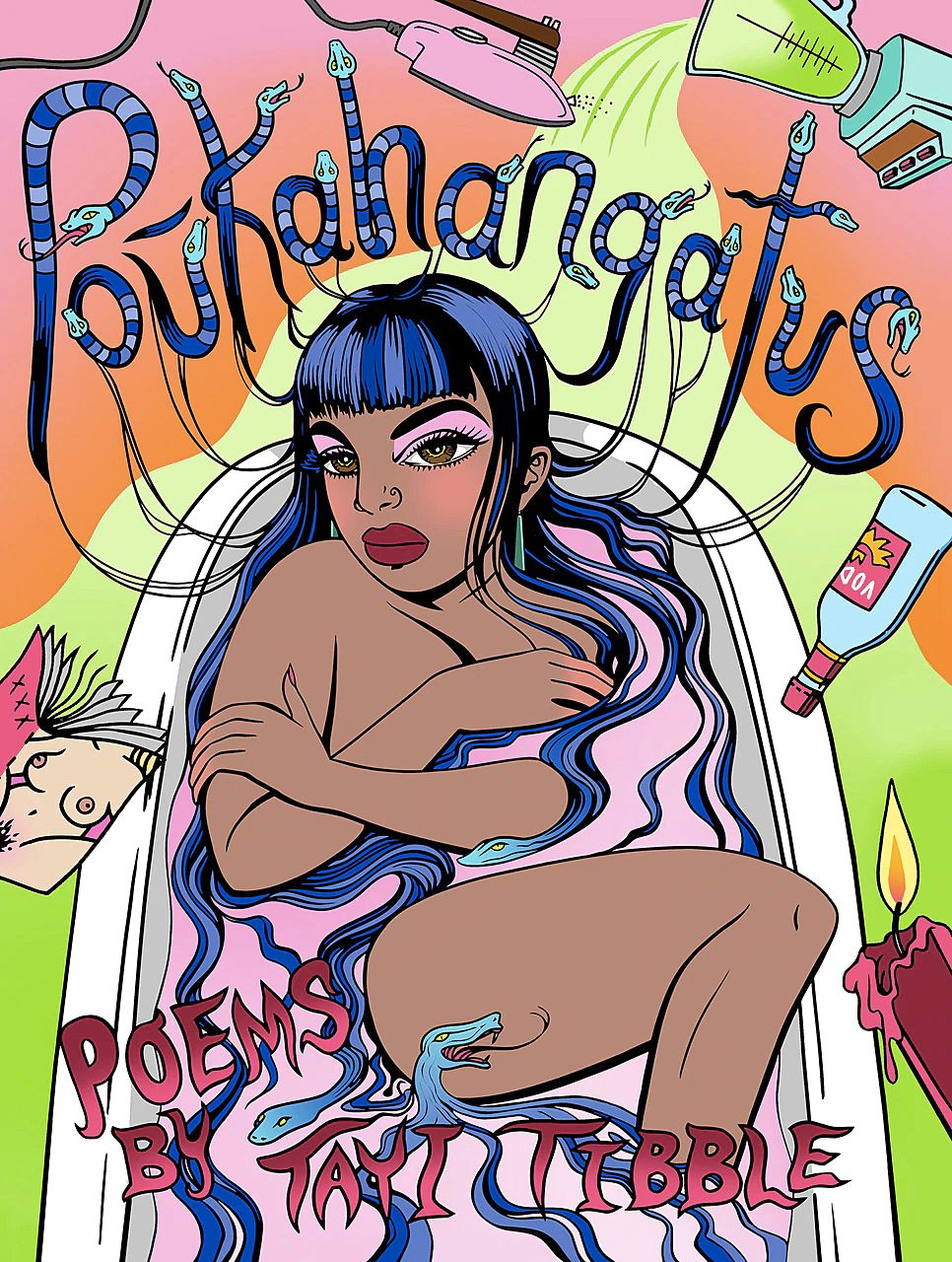

Poūkahangatus by Tayi Tibble

(VUP, 2018)

Tayi Tibble’s debut poetry collection is topping a lot of end-of-year lists – and rightly so. It is a remarkable book by a bold and talented writer who has things to say. Tibble’s poems look out not only to lovers, friends and family, but also to history and what it means to be Māori. She writes about celebrity and relationship fantasies in one poem, and the lived experiences of colonisation in the next. One of her notable skills is an ability to write personal poems that reverberate with social and political significance – some very overtly, others more quietly.

Parts of this book are confronting to read. Tibble seems unafraid to write into difficult spaces. Her poems surprise and satisfy with their shrewd observations. With much of the book written in conversational, prose-poem style, the power is in its cumulative effect rather than individual lines, but I love these lines from ‘LBD’: “I grew up / on the sound of women wailing / now they wail for me / I carry them inside me / bones vibrating like a ringtone”. —Hannah Newport-Watson

The Imaginary Lives of James Pōneke by Tina Makereti

(Penguin, 2018)

Days after finishing Makereti’s new novel, I was still thinking it through—mulling on its big themes: the twinned violence of colonisation and its subsequent exhibition, cross cultural exchange, love, subjugation and desire. I love how Makereti manipulates time in her writing. Although The Imaginary Lives is more linear than Makereti’s earlier book Where the Rēkohu Bone Sings (which shuttles between the modern day and nineteenth century Aotearoa), the first third is somehow, cleverly, both fast and slow. It begins during the period of early contact between Europeans and Māori, and the young Pōneke is propelled along in a rapid succession of events. He then encounters a hapū displaced by war, walking towards Wellington. At that point, Makereti’s prose slows down and these affecting scenes ache with trauma.

The Imaginary Lives is framed so that Pōneke is writing the novel for his mokopuna in the future. In this way, Makereti’s book points outside of itself to a potential future; the novel is not an end point in itself; words and people are one point in an interconnected chain of being. —Thomasin Sleigh

Queer the Pitch edited by essa may ranapiri

(Self-published, 2018)

“The process of writing poems from a queer experience is a process of rewriting or un-writing certain expected norms,” poet essa may ranapiri writes in their introduction to Queer the Pitch, an anthology of poetry from LGBTQIA+ people across Aotearoa. I’d been feeling a bit disconnected from new Aotearoa literature until I received in the post this exquisite poetry zine edited by essa. Featuring work by 19 young, queer Aotearoa writers, this slim booklet contains poems that are like bodies in motion, poems like spells and protective charms, poems made of thread unspooling. Hana Pera Aoake traces “cycles of beginnings” under their skin:

I am not graceful but it does not matter

A taniwha lurks in my skin and u say u can feel it

Hands swimming over my stomach

Transactions of history.

So many poems stood out to me, but it’s worth getting your hands on a copy just to read Jackson Nieuwland’s heart-rending, kaleidoscopic poem ‘The Things In My Chest’: “a cave which becomes a tunnel which becomes a hallway which becomes a waterslide…” Jiaqiao Liu and Sam Duckor-Jones possess a similarly tight grip on language, while Rebecca Hawkes’ poem ‘Softcore Bushwalk’ pulled me into an undergrowth of want. This is essential work that is constantly shifting, spell-casting, making and re-making itself before our eyes. —Nina Powles

The New Ships by Kate Duignan

(VUP, 2018)

The New Ships, Kate Duignan’s second novel, is beautifully, perfectly written; a swirl of family, memory, myth, music and humanity. It's a novel I want to read again, which is a rare desire in these time-poor months. The New Ships is forever suspended in my memory as a marker of that momentous change – becoming a parent. I was half way through reviewing the novel when I went into premature labour, and during the hormone-high days following my son’s birth I finished the review. The way I read the book and related to the main character (a man, a lawyer, a father) completely changed. If you want to find yourself absorbed in a story that resonates with the very foundations of the concept of family, then read this book. —Claire Mabey

field notes on a downpour by Nina Powles

(If a Leaf Falls Press, 2018)

It’s been quite a year for Nina Powles. On New Year’s Day she arrived in London, suitcase filled with the ephemera of other homes – Shanghai, Malaysia, Eastbourne. It wasn’t long before she established her presence in England, winning first the Jane Martin Poetry Prize in May and then the inaugural Women Poets’ Prize in October.

field notes on a downpour is a small twelve-page publication that Powles released this year. It contains eight morsels of memory and discovery, found between the entries in a Chinese–English dictionary, or in the action of shattering a glass jar of honey.

Powles’ publication is a declaration that we are made of parts that are each a whole. The first character of her mother’s name is made from rain and language, like a lover’s murmur in the dark or a ghost emerging from between two trees. Powles’ own name is so bright that it contains both the sun and the moon. Her writing invokes the mood of transition, of reforming, of tasting the word that’s on the tip of your tongue. —Rose Lu

Editor’s note: Unfortunately, field notes on a downpour is not available for readers in Aotearoa to buy, but you can order copies of Nina’s other brilliant collections Girls of the Driftand Luminescent from local indie publisher Seraph Press.

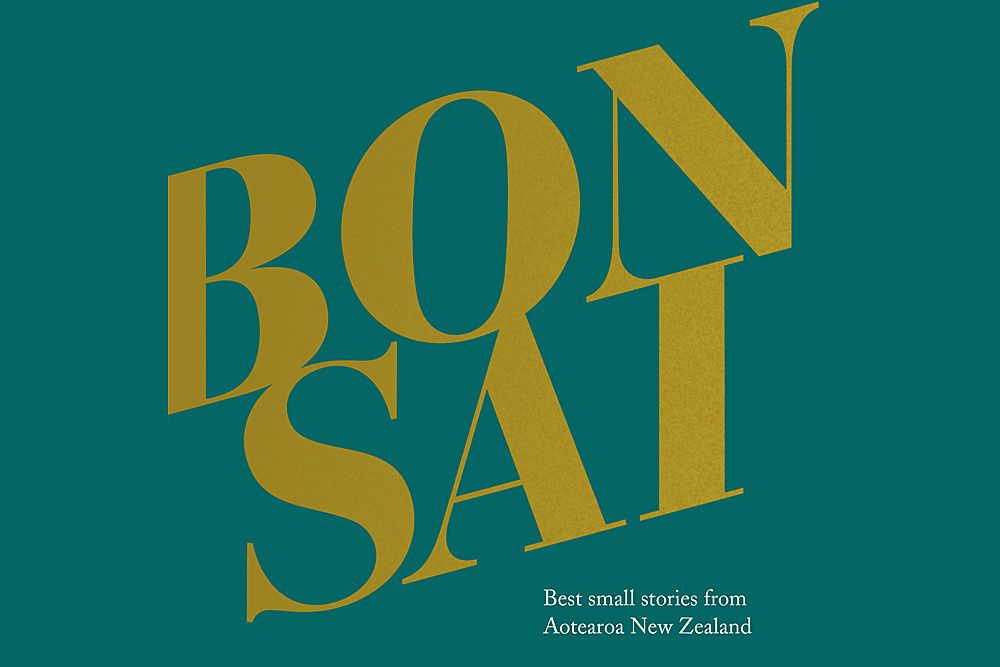

Bonsai: Best Small Stories from Aotearoa New Zealand edited by Michelle Elvy, Frankie McMillan and James Norcliffe

(CUP, 2018)

Lush specimens of flash fiction, prose poems and other very short forms have been carefully collected together in Bonsai: Best Small Stories from Aotearoa New Zealand, and the result is like looking inside a brilliant kaleidescope. As a lover of prose poems, I’m delighted by the appearance of some absolute classics of the form, such as Rachel O’Neill’s ‘The children have grown’ and Gregory O’Brien’s ‘Love poem’. The editors seem to have distinct taste for the slightly off-beat, in keeping with editor Frankie McMillan’s own story, ‘When gorillas sleep’.

“They ask a lot of work from the reader,” said Louise O’Brien in her RNZ review. And she’s right; the collection is full of enigmatic little pieces like Courtney Sina Meredith’s ‘American Journal’, which demand active reading. But with such short forms, it’s also well-suited to be dipped into at leisure. It’s a brilliant, invigorating collection. —HNW

Tess by Kirsten McDougall

(VUP, 2017)

Gothic love story Tess is Kirsten McDougall’s second book (her first, The Invisible Rider, was published to critical acclaim in 2012). The book has had a good year: it was longlisted for the 2018 New Zealand Book Awards Fiction prize, and was a finalist in the 2018 Ngaio Marsh Awards.

McDougall’s story is set in Masterton at the turn of the millennium. Tess is on the run when she’s picked up from the side of the road by a lonely middle-aged father Lewis Rose. As the story progresses, Tess is drawn into his family’s troubles.

McDougall’s spare and beautiful prose captures the raw experience of being nineteen, from Tess’s clashing desires for connection and independence, to her burgenoingburgeoning sexuality. While Although Tess was published late 2017, I’m still dwelling on the story – I wish I’d been able to read it as a young woman, and I hope that many do. —Sarah Jane Barnett

People from the Pit Stand Up by Sam Duckor-Jones

(VUP, 2018)

People from the Pit Stand Up, the debut collection by Sam Duckor-Jones, starts off laconically, with the poet as a quiet onlooker, listening and observing with sensitivity and a sense of humour to the characters of a small town. A native bird appears in almost every poem.

The collection turns slowly inwards, examining the strange life of the artist as a maker. Clay men appear and their existence morphs in pleasingly mysterious ways as creations, as progeny, as lovers, as reflections of self. The book echoes with loneliness, melancholy, gentleness and roughness by turns. What I loved is how rich the book is with both language and physicality. It takes its time and does nothing in a hurry – a collection to be read slowly, and returned to. —HNW

My Body, My Business: New Zealand Sex Workers in an Era of Change by Caren Wilton

(OUP, 2018)

Eleven former and current New Zealand sex workers tell their stories in the book My Body, My Business: New Zealand Sex Workers in an Era of Change by Caren Wilton. I found these first-hand accounts compelling reading, appealing to my deepest human curiosity about other humans. They are also fascinating for their local contexts – these are distinctly New Zealand stories, even if they are ones we are not accustomed to hearing.

The personal accounts, which are based on oral history interviews, are framed by a thoughtful preface and an introduction by Wilton about the history of sex work in Aotearoa. In her preface, Wilton also pays homage to other oral historians writing in Aotearoa. This book is itself is a compelling testament to the power of oral history and its ability to enable under-heard voices to be surfaced. You can read an extract here. —HNW