You Treat Us Like We're The Virus

Racism sucks. Vanessa Crofskey writes about the hurt her and her peers feel as Chinese people during Covid-19.

Covid-19 recently got nicknamed the ‘Chinese virus’. It was something stupid that Donald Trump said and that other people echoed. Renaming the virus was a crudely obvious tactic that most people could clearly see through: associating a worldwide pandemic with the race who were the first exposed to it, a race whose identities are already associated with spread and terror. The point of that association was to inflict blame, to connect disease and Chineseness together, to let that whir in the back of people’s minds, whether they recognised it or not. It’s particularly effective not because it’s smart but because it’s got historical roots: inciting a particularly nasty part of history that has routinely stoked the idea of Chinese people as dirty, backward, diseased.

*

Back before the borders closed, before the What-Big-Brother-Doesn’t-Know, before Tom Hanks and Idris Elba, people were deathly afraid of this impending virus that hadn’t yet arrived. Supermarket fights about toilet paper still felt novel and ridiculous. People didn’t know what to be afraid of; but they were deathly afraid of us. I watched the internet fall into a crazed panic about the origins of this virus, making jokes about what-kind-of-food-these-people-ate, crafting conspiracies about government blackouts and who should be to blame. Back when it didn’t affect you, it affected our families, it affected Asia. I watched your silence. I wept for Wuhan.

I watched your silence. I wept for Wuhan

The Lunar New Year is my favourite celebration, a festival of love and food and offerings. This year, we were gathering up friends and family over noisy, round, spinning tables, like every other year. Asian families travelling home to celebrate Lunar New Year form the world’s largest annual mass migration. Then this thing happened. This virus started spreading. Suddenly we couldn’t get home or our family couldn’t return home, and we were afraid and sad and unsure what to do for our relatives half a world away. My friend Hannah, who hails from Wuhan, told me that her family were locked into a city that was running out of supplies, that some of her aunts and uncles were looking to be quarantined like criminals on Christmas Island should they wish to return home. It felt like a nightmare.

*

Now everyone is worried about supplies and toilet paper. The virus has fast become a global situation. It’s impossible to find anyone who is either unaware of Covid-19 or unaffected by its knock-on effects. Things have ramped up at an unprecedented scale, so much so that my feelings from yesterday start feeling quickly outdated. The entire situation is different from what it was a week ago. It feels beside the point now, to bring up how hard this has felt for me, as a person who has Chinese heritage, because this pandemic spans more than any one ethnic group. But I’ve been angry at how Chinese people feel like the blind spot of Western empathy. I think that we need to address that. I think that I need to.

Things have got worse right now for Chinese people, in terms of how we’ve been treated because of this virus, but like hell is it new. I’m hearing experiences told over the internet ranging from hostile eye-contact and verbal abuse to being stabbed and assaulted in broad daylight. What are you so afraid of?

*

Before the virus inflicted travel bans across the world, many countries, including the United States of America, Canada, Indonesia, Australia and New Zealand, had historically set multiple laws that prohibited Chinese people from entering their borders. We were – and are – your yellow peril, your oncoming invasion, the pandemic on your shores. Our presence is a nightmare, a “deteriorating effect upon civilisation” (Sir George Grey, 1807), lest we “[raise] a yellow colony in [your] midst.” We are the “colour taint” (The Free Lance, 1904) and the “Asiatic terror” (White New Zealand League, 1938). From the New Zealand Mail, 1907: “The Chinese have numbers of their women here, and their women are fecund…it is a gross and bitter evil and the malignity of it increases with every child of Chinese blood born in this country”.

Most of the Asian people raised in New Zealand that I know carry a sense of shame in their stomachs, about not belonging. It’s not hard to see why. These quotes, collected from the book Unfolding History, Evolving Identity (edited by Manying Ip) illustrate the historical media lens toward Chinese in our country. Although our identities are more complex and multi-toned now, these words have always been associated with who we are. And if we don’t know that in our heads, we know that in our bones.

*

Discussions of eugenics resurface on my Twitter timeline. I begin to feel sick. “Thank God this has happened in China because they can afford to lose a few thousand people. They have such a big population, it doesn’t matter how many of them die.” It doesn’t matter if we die. It doesn’t matter if we die. Our lives never mattered. To you, our lives never mattered.

*

At a workshop on being Chinese, one participant reveals a story about going to the gym. “I knew as soon as the virus hit, that people might not want to be around me anymore. So I started choosing the treadmill that was closest to the wall. That way, only one person would have to choose to be next to me. One day a white woman came up to me and I thought, finally, this is it. She’s going to ask me to leave. I braced myself for what was coming. She told me she liked the dress I was wearing.”

I and most of the Chinese people I know have had our stress levels rise in a subconscious oh-God-this-is-about-to-get-real-bad sort of way. We knew that things were going to be bad for Chinese people, no matter where they were based or from. We knew that an entire ethnicity, one that was suffering and grieving from its own tragedies, would be blamed. Not just blamed, but castigated. Thrown to the dogs. Set alight.

Chinese people feel like the blind spot of Western empathy

Living in Auckland, it’s hard not to feel pervasively stressed on the daily. My Chinese friends and I agree that our daily lives are routinely made up of obsessive hypervigilance in our thoughts and behaviours. Every time I’m on Queen Street, I estimate the number of Asian people next to me at a crossing. I need to see if it would look like too many Asian people to your everyday New Zealander. I count the number of black-haired people on a bus and wonder if anyone will notice or make a comment about it. We back ourselves into corners trying to prove we’re not a threat to you.

I didn’t associate with being half Chinese as a child. I hated Chinese things, I hated spending my Saturday afternoons going to Chinese language school, I hated having people come over to my house with its Chinese objects and my Chinese mother and that clear, obvious, Chinese taint. I made myself small, smaller, invisible. As a child, you instinctively find ways to protect yourself from harm. But now, it feels impossible.

*

Even as Western colonialism has spread a barrage of death and disease across Asia, it is Asian people, not Italians or the British or the Dutch or Americans who have been treated like a virus, like inferior, lower-class beings, carriers of foreign malice. Even before Covid-19 our lives and daily behaviours have always seemed suspicious.

*

The taxi driver on the way to Kuala Lumpur International Airport hands my mum and I a pack of face-masks. He warns us that we need to wear these, especially if we look Chinese.

I walk past two people on my way to the library. They’re laughing. “Do Chinese people wear masks because they’re worried that we’re sick, or is it because they’re going to get us sick?”

I walk past usually-bustling restaurants on Dominion Road, sad and quiet and empty.

*

Perhaps I’m still not over the death of Wang Xi. I’m still grieving the fact that our deaths don’t seem to matter to anyone outside of our community, so all I seem to want to talk about is this big, big hurt inside of my belly.

Wang Xi was the victim of a brutal murder, her death made public a couple months after Grace Millane’s was. I saw rightful fear and heartbreak over Millane’s death, but those crowds of thousands had quietened to a mere handful of people by the time Wang Xi’s vigil was held in Aotea Square. I know you can’t measure the extent of someone’s grief or life by numbers, that you shouldn’t compare the ways people express sorrow. You don’t get anywhere by counting a crowd, but what else could I do?

The Chinese woman stabbed to death by her Pākehā ex-partner in Tāmaki Makaurau barely made it to our national consciousness. I thought of this woman and how much her life felt like it mattered to me, how it felt like she didn’t matter as much to other people. After riding it out for a couple of days, I burst into tears on a crowded bus. I heard you then: that Chinese people are replaceable. It doesn’t matter if, and how, we die.

We back ourselves into corners trying to prove we’re not a threat to you

I still haven’t read Edward Said’s book Orientalism, but I know the shame of carrying something foreign within you. “These bloody Chinese,” a man driving me home mutters under his breath. He doesn’t yet know I’m half-Chinese, though he keeps inspecting my face, asking sly questions. I am a study in perfect neutrality. I give him a false home address.

Chinese people are well-known for saving face and acting neutral. It’s a survival tactic to prevent becoming expendable targets. As a result, people think we’re fucking emotionless. Maybe they don’t realise how much of ourselves we’ve been forced to hide for so many years, so much that is buried away because we’re rarely, if ever, given a chance to be fully human.

*

It’s unfair of me to say that the only thing Chinese people are receiving right now is hate. That’s just the wound that is the loudest. The idiots saying “Thanks a lot, China” to breaking updates about deaths and quarantine have been mocked online. It’s satisfying. There have been videos, memes, love and support, funny and painful retorts against being targeted. My WhatsApp has been pinging constantly, offering sounds and sources of comfort.

Yet the jokes still hurt, and they still make me scared, because they speak to a wider historical truth: we are not wanted here. No matter what we do, it’s not enough to assert our belonging. This essay from a Chinese-American writer speaks on just how fast our status as the mythical ‘model minority’ unravels, how hate crimes against Chinese people have been historically deemed okay, especially if it means “tackling a threat to public health”. We are seen as the threat to public health. That makes it okay to treat us like a virus.

No matter what we do, it’s not enough to assert our belonging

How fast we become implicated. How quickly you revert us back to being members of triad clans and secret ministers with second agendas. How easily these notions of nation and unity crumple under pressure. How villainised and unimportant our tragedies were until they came to your doorstep. I feel like half of me is absolutely hated. Half of me is dog shit to you. The people in China at the front lines who have been trying to protect you, who have sacrificed their lives in order to delay the impact of this virus upon your lives, have had their motives endlessly interrogated.

I wish I could feel kindness instead of anger at this moment, that I could say that compassion was all we needed to make the world a kinder place. But I’m still in pain from the way you have treated Chinese people, for the ways that I have been treated, the ways that people I know have spoken in passing about Asians, usually without realising what they are saying. I’ve been in pain since I was six years old.

The world is hurting, we all are. I’m not sure when this virus will pass, but I know my people need to brace ourselves for worse. Now might not be the best time to bring up this pain and rage, but then when? When will you have space for us?

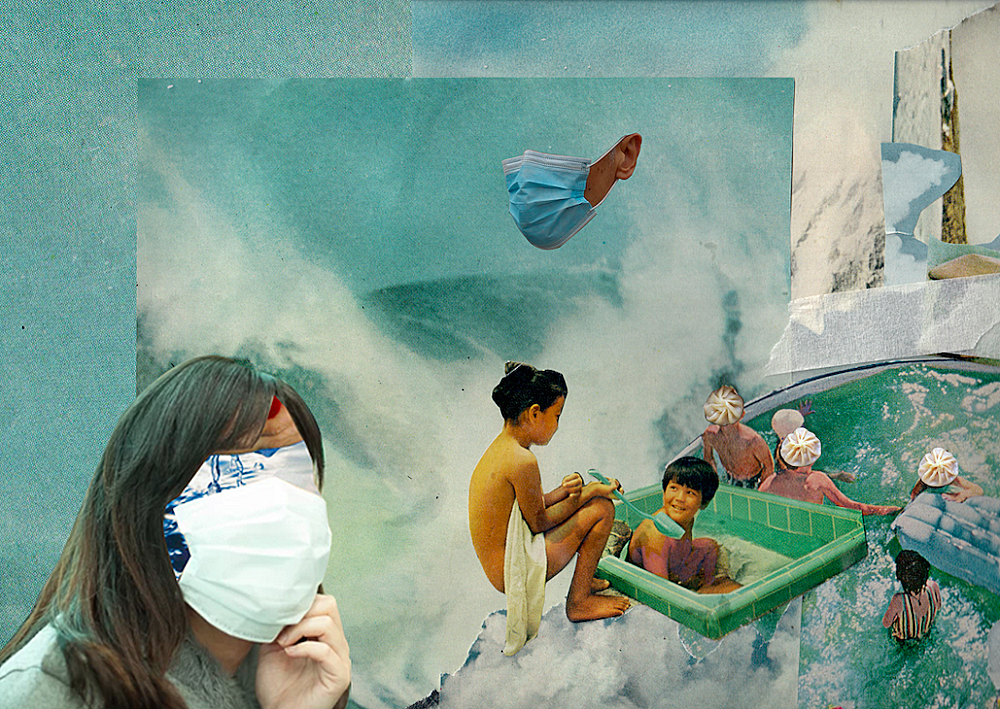

Title image: Vanessa Crofskey, Smoke signals. Made for the Te Tuhi Billboard series, 2019.