The Fragility of Mystery: Exploring 'Yang Fudong: Filmscapes'

Francis McWhannell explores 'Yang Fudong: Filmscapes', an exhibition of moving image art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Francis McWhannell explores Yang Fudong: Filmscapes, an exhibition of moving image art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

In an immediate sense, Yang Fudong: Filmscapes represents an important and exciting event. It is the first solo show in Australasia of one of China’s most renowned contemporary artists (Yang’s work has appeared in such illustrious contexts as documenta and the Venice Biennale); a second large-scale exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki of moving image art, immediately following Lisa Reihana’s much vaunted in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015); an affirmation – as Director Rhana Devenport has indicated – of the Gallery’s commitment to its Chinese patrons, from both Auckland and abroad; and an opportunity for visitors like me who know relatively little about Chinese art (to say nothing of Chinese history and culture more generally) to broaden our horizons.

Co-produced by the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne, where it premiered in December 2014, Filmscapes has been curated by ACMI’s Ulanda Blair, with assistance from Toi o Tāmaki’s Zara Stanhope. The local version of the exhibition comprises three installed works: Ye Jiang/The Nightman Cometh (2011), The Fifth Night (2010), and The Coloured Sky: New Women II (2014), this last having been specially commissioned for Filmscapes. (The ACMI version included a fourth work, the gritty East of Que Village (2007).) A one-off screening of Yang’s most famous work, the five-part Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest (2003–7), was also held shortly after the exhibition opened in Auckland in September last year.

In its current format, Filmscapes is a pleasingly concise survey of Yang’s art. The works play off each other well, and one can dedicate them the requisite attention without feeling too fatigued. The main entrance to the show brings the visitor to Ye Jiang/The Nightman Cometh, a single-channel black-and-white piece that runs for just under 20 minutes. More conventional than the other works on display, and rather less immediately striking, Ye Jiang nevertheless demonstrates many of the hallmarks of Yang’s practice. As with the other works, it uses an elaborate set that feels by turns artificial and realistic. Like them, it is wordless and heavily gestural, suffused with haunting music (here composed by Jin Wang), and resolute in its visual stylishness.

The film centres on a battle-worn soldier, in broadly historical garb, who awakes in a snowy mountain pass, surrounded by the vestiges of some sort of attack, including broken cartwheels, armour, and weaponry. The wall text informs the viewer that the protagonist is ‘questioning his path in life’, trying to decide whether to keep fighting or to retire. The soldier is joined by three other human figures: a woman in similarly generic antique attire, described by the artist as a ‘princess’, and a ghostly man and woman in white costume associated with 1930s Shanghai (the woman wears a cheongsam). Also included are a host of animals: the soldier’s horse, a group of deer, and a hawk.

The action is minimal. The soldier plants a spear in the snow and starts a fire under a cooking pot. The princess feeds a deer. The 1930s man touches some blood on the tip of the spear, then wipes his fingers on a handkerchief. The 1930s woman discovers the blood on the handkerchief and begins to cry. The hawk beats its wings dramatically. The soldier rides his horse away. That is about it. With the exception of the horse, the soldier does not interact with or display any awareness of the other figures, whether human or animal. One begins to wonder whether they might be less physical presences than manifestations of the soldier’s psyche, and, indeed, the wall text seems to confirm this.

For his part, Yang has indicated that the figures carry symbolic significances. The princess, he claims, represents purity, the couple the ‘uncertainty of the future’, the horse loyalty and trustworthiness, the deer purity and family. The hawk is to be understood as a double of the soldier, as well as a symbol of spirituality. The Chinese title of the film,《将夜》(sometimes romanised as a single word, ‘Yejiang’), may be read as ‘general at night’ and ‘imminent night’, both senses being literally descriptive, since the piece evokes nightfall, while allowing for more portentous interpretations. The English title, The Nightman Cometh, is rather more overtly ominous, suggesting the approach of something sinister.

So, what does it all mean? Taking the artist at his word, one might reasonably understand Ye Jiang to be an abstraction of the decision-making process, the soldier standing in for anyone presented with the proverbial ‘two roads’ – seeking, for example, to act with pure intentions, to do right by family, and to anticipate/avoid negative consequences, while worrying that a wrong move will lead to darkness. Other interpretations are entirely possible. One might wonder whether Ye Jiang reflects the artist’s life – particularly, the transition from his conservative military childhood to his cosmopolitan career as an artist. (It is worth noting that at least two earlier works by Yang, The Revival of the Snake(2004) and The General’s Smile (2009), also centre on soldiers.)

One might suppose, as so many critics have supposed of Yang’s work in general, that the film treats the tensions of contemporary China – particularly, the navigation of the traditional in a time of rapid change. Although he has often denied that his art is directly political (he has commented, for instance, ‘I’ve never thought of the connections between my films and the state of Chinese society or politics’), Yang does not appear to be averse to the diverse readings that viewers might make. In fact, he has repeatedly stated that he considers the audience to be the ‘second director’, bringing additional meanings to his work. While this might sound like a statement of the obvious, and perhaps even a little like evasion on the part of the artist, it also indicates that it would be a mistake to seek a single, definitive interpretation of Ye Jiang.

It would be a mistake to seek a single, definitive interpretation of Ye Jiang... the piece may be understood to depend on ambiguity, playing on ill-defined boundaries between periods in time, the factual and the fantastical, the living and the dead.

Indeed, the piece may be understood to depend on ambiguity, playing on ill-defined boundaries between periods in time, the factual and the fantastical, the living and the dead. At the same time, the film is ostensibly an aesthetic/sensual exercise, as well as an intellectual one. For the artist, it provides an opportunity to play with modes that interest him, such as the nature motifs of traditional Chinese painting, the fashion of 1930s Shanghai, and the visual and narrative styles of European art cinema (Yang has cited Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, and Ingmar Bergman as influences). For the viewer, it provides an opportunity to enter into a dream world of the artist’s making. (Writing this piece, I keep finding myself wanting to call the exhibition ‘Dreamscapes’, as its actual title fails to capture the fabulous quality of the art.)

Moving into a space immediately adjacent to that housing Ye Jiang, the visitor encounters The Fifth Night (the closeness produces a tolerable level of noise pollution). Like the former piece, the latter is in black and white and without clear narrative. Unlike the former, the latter is a huge multi-channel work, whose characters feel as though they inhabit the same reality. Shot during a single night (apparently a Friday, the fifth night of the week), the film comprises seven pieces of footage (each the length of single reel, just over ten minutes), which show the same scene from different angles. Projected synchronically onto a line of identical screens, it is not immediately apparent that the scenes are simultaneous. This becomes clear as one identifies common reference points, or observes characters moving between screens.

The artist has indicated that the horizontal arrangement of the screens is meant to suggest Chinese handscroll paintings. Also evocative of such artworks are the multiple perspectives and depths presented in The Fifth Night, its division into sections that invite individual inspection, and the use of panning and tracking shots that mirror the action of one’s eyes roaming over/through a painted landscape. Perhaps more apparent are the work’s filmic resonances. The piece is generally understood to pay homage to pioneering Chinese films of the early twentieth century. As in Ye Jiang, the influence of European art cinema is evident. The air of foreboding is strongly suggestive of film noir.

Again, the action is minimal. Most members of the cast wander about the city square looking sullen or dejected, seemingly lost in their own thoughts. The only sound, besides the rather melodramatic music (again by Jin Wang) is ambient: horses and vehicles moving through the scene, a blacksmith working, a group of men repairing what appears to be a bus. In concept, the piece sounds as though it should be something of a disaster. In actuality, it is not. The ponderous camera movements and understated expressions of the actors contrast the excesses of lighting and music, creating remarkable emotional tension, while the cubist use of viewpoints potently evokes the varied and discrete subjectivities that necessarily exist within a group of people.

An additional dimension emerges when one considers the specific historical moment alluded to in The Fifth Night. Filmed at the Shanghai Film Shooting Base, which includes a number of recreations of the city in the 1930s, the work centres on a square of the period (an opening shot reveals the date 1936 on a building), possibly in the International Settlement, as suggested by a telephone booth with English-language signage. It thus evokes a turning point in the history of Shanghai, a city known for its cosmopolitanism and cultural vibrancy in the 1920s and early 1930s, but substantially altered by the ravages of the Second Sino-Japanese War, which broke out in 1937.

This is not to say that the piece is fundamentally a commentary on an important moment in the history of Yang’s chosen hometown. Nor do I think it should be read simply as an analogy for the China of today: in a state flux, uncertain of its future. As with Ye Jiang, the work seems more interested in using a mixture of artistic modes – pictorial and cinematic, historical and contemporary, Eastern and Western – to reflect broad human experiences, such as remoteness, disjointedness, and inconclusiveness. The piece succeeds because the eclectic elements that inform it remain secondary to the chord of timeless melancholy that it emanates.

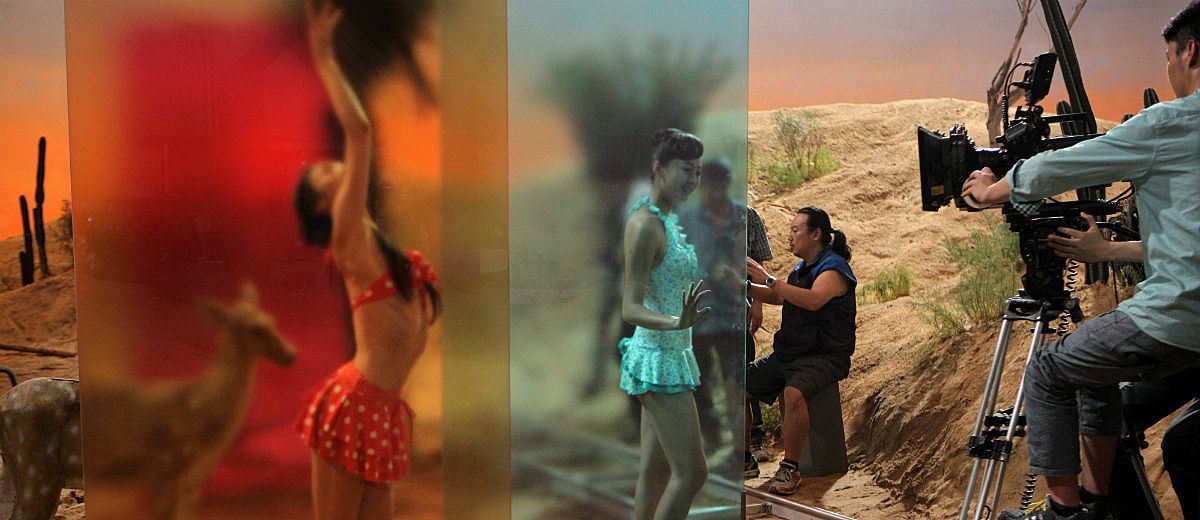

Separated from the other works in the exhibition by a long corridor, The Coloured Sky: New Women II comes as something of a surprise (even if one has seen promotional stills or video previews of the piece). Though it shares much in common with The Fifth Night and Ye Jiang, its intense colour and gentler music (this time by Wang Wenwei) make it a very different experience. The installation comprises five pieces of unsynchronised footage, which loop continuously on a series of screens – one portrait, four landscape – irregularly arrayed around the intimate exhibition space. For the most part, the work centres on a coterie of petite belles, dressed in retro swimsuits, and inhabiting a fantastical landscape – part beach, part desert.

As hinted at by its subtitle, The Coloured Sky grows out of an earlier piece by Yang titled New Women (2013). This five-channel black-and-white work was apparently intended as a tribute to 1930s Chinese cinema, including Cai Chusheng’s eponymous film about the struggles of an independent modern woman, lusted after by a succession of men, and finally destroyed by them. Yang’s piece concentrates on languid naked women, ideally beautiful and classically posed, and is predictably ambiguous. Are the subjects to be understood as akin to the protagonist of Cai’s film: objectified, vulnerable, confined? Or are they fundamentally different: self-possessed, powerful, free?

In attempting to answer these questions, Yang’s comments prove rather unenlightening. His suggestions that the work is ‘the depiction of the perfect woman image in each person’s heart’, but that ‘there is difference between reality and dreams’ leave it unclear whether the piece is an interrogation of the endless stream of artworks centring on the perfect woman, or one in the stream. Whether one finds the piece admirable and intriguing, or, as Sam Gaskin has put it, ‘politically iffy and dangerously uninteresting’, comes to depend on the extent to which one is willing to give the artist the benefit of the doubt.

Whether one finds the piece admirable and intriguing... comes to depend on the extent to which one is willing to give the artist the benefit of the doubt.

Much the same applies to The Coloured Sky. In an interview with Zara Stanhope in the Filmscapes catalogue, Yang indicates that the work takes its inspiration from the image of lolly wrappers held up to sunlight (hence, it seems, the structures of translucent/reflective acrylic that pepper the scenography). He explains that the piece is ‘about young girls in their room or private space’, and that it ‘attempts to convey the sensation of a girl with a special, secret gift’. Ignoring for a moment their rather suggestive connotations, these comments indicate that the work is concerned with getting at the enigmatic interior lives of girls – girls who, going by the choice of actors and the title of the piece, are at the point becoming women. The Coloured Sky may thus be understood as the girls’ fantasy of their adolescence.

But is the fantasy exclusively or essentially theirs? Apparently not. Though they sometimes look serene, joyous, or otherwise uninhibited, most everything that the young women seems conditioned from the outside. When they frolic in the water, attend to a horse, engage in a pillow fight, they feel as though they are enacting stereotypes of girls’ own fun. Their movements, expressions, and poses – to say nothing of their immaculate presentation – appear less for themselves than for an audience, especially a male one. They are surrounded by a host of sexual symbols: seashells with fleshy-looking openings, turgid cacti, a glistening snake. (It should be noted that Yang has indicated that, in his films, ‘the snake symbolises the winding future, the future that is changeable, the future that is not straightforward’.)

The young women are not without agency, but they also feel confined, like the caged nautilus and the fish in the bowl that decorate their dining table. They appear aware of themselves and of their allure, often meeting the viewer’s gaze, and occasionally seeming to challenge it. However, knowing is not bliss, and their faces often show signs of sadness or discontent. Ultimately, as their bodies are reaching full ripeness, any sense of innocent freedom is decaying. It’s an intriguing exploration, not only of the process of growing up female, but also of the complex make-up of our selves – part innate, part habituated, part authentic, part fake.

Or so a generous viewer might opine. A less generous one would point out that although The Coloured Sky is much the more intricate work included in Filmscapes, it is also much the less assured; that, at times, the work feels like it is trying to do too much, as though Yang has attempted to cram into it every idea he has ever had, every symbol he’s ever used; that, at times, the work feels like it might not be doing very much at all, as though Yang has taken a basically banal, middle-aged male fantasy of mysterious near-naked maidens, situated it in a Mark Rothko-cum-Truman Show set, and embellished it with some clunky references to vanitas paintings and the Garden of Eden.

For my own part, I find it difficult to make up my mind about The Coloured Sky. There is a part of me – probably the part that is acutely aware of and embarrassed by the limitations of my knowledge of China – that wants to believe that the work conceals a more political meaning, that it might, say, double as a rather ingenious figure for a new generation of Chinese people ‘coming of age’ under the watchful eye of an older order or the wider world. And yet, I struggle to convince myself, perhaps because of Yang’s avowed disinterest in politics, and because he has indicated that his work is not made with a particular audience in mind. Could this simply represent caution on the part of the artist? I don’t know.

I find myself wondering if I might do better not to fixate on Yang’s status as an artist of import, not to make too many allowances for unfamiliar allusions or unapparent significances. Fundamentally, I appreciate the works in Filmscapes most when I am not straining to decode them. That is, the works impress me most when they do not feel as though they are straining to be sophisticated. The artist does best when he presents simple images: a deer twitching its ears in the snow in Ye Jiang, two bewildered men stuffing clothes into suitcases in The Fifth Night, a horse drinking casually from a make-believe sea in The Coloured Sky. I end up hoping that Yang will come to realise that while a measure of enigma can make for a rewarding art experience, an excess can end up looking like indulgence, or, worse, well-dressed emptiness.

Yang Fudong: Filmscapes

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

26 September 2015 to 25 January 2016

Free admission