Review: Wolf In White Van

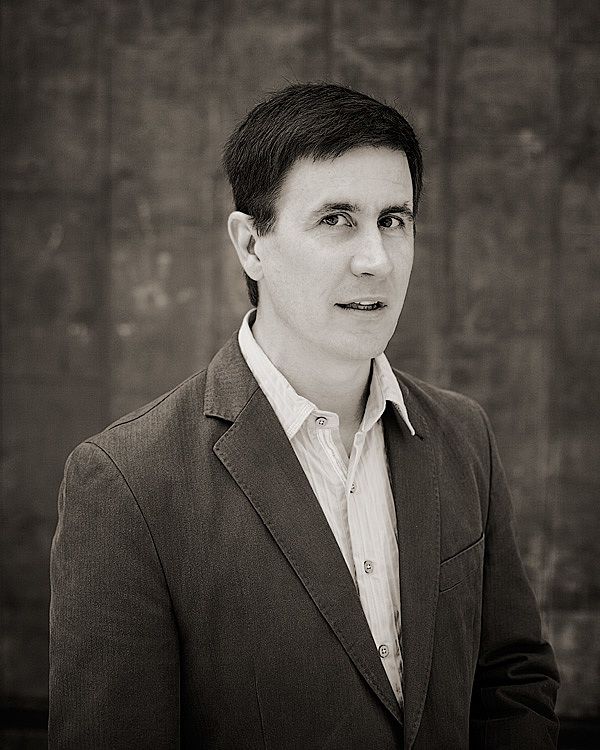

Kieran Clarkin on John Darnielle's haunting first novel.

Ever heard of the Alpha couple? Their story spans across years and across the continental United States: drinking buddies turned lovers, two dysfunctional addicts cause each other ruin, first unintentionally, then gleefully. Through the bad times and then through the worse times, sticking around solely out of spite for each other, until it abruptly ends. You might be thinking of Raymond Carver or Denis Johnson, but this is pure John Darnielle. One of my favourite American pieces of writing, told not in prose but as an asequential song cycle over several albums. Given this penchant for long form storytelling, and the pinprick precision which makes his best songs function as short stories, it's less surprising that the Mountain Goats' frontman would write a novel than that it took him so long to do so.

Wolf in White Van is a memoir told by Sean Phillips, a man horribly disfigured in his teenage years in an event referred to vaguely at first and then more specifically later, the narrative circling the traumatic episode like a drain. Sean lives alone but requires regular medical assistance. He supplements the insurance payments for his rent and care with the small income he receives as gamemaster of several mail-in role-playing games, the most popular of which is called “Trace Italian”.

The novel works in a way that makes everything in the previous paragraph seem like a spoiler. Sean initially appears to be an unreliable narrator, and I was initially concerned that he may be the Wolf of the title: something uncontained, purely malicious. I didn’t want to read that story - the psychopathic anti-hero, though the story at first flags that it might go there. Early on, a child says to Sean “You’re a fibber” in response to a truthful, yet incomprehensible answer. But Sean doesn’t lie. His omissions are overt and commented upon. He is honest about his inability to recollect clearly; in the way that memory is fluid and fallible. He is a storyteller, telling stories to himself, the players of his games, and to the reader.

Through each meticulously recounted and narrowly focused chapter, the story comes into whole, culminating into a complete object by the final lines. The novel resembles a multi-faceted prism, black with soot, being wiped spotless one plane at a time: the reader finally left with a clear crystal, hard and dense.

Despite being largely concerned with only two pivotal events, and how the fallout from the first leads into the second, the novel covers a lot of ground in terms of modern American social psychology. The trappings of teenagehood are all here: illicit cigarettes, sexual awakenings, music, confusion and obsession. The bullied teens who disappear into escapist games and stories. The role of fantasy in a culture of violence and escapism. Parents attempting to comprehend the behaviour of their offspring. This is contrasted with Sean’s maturation and progression to adulthood, facing the daily reality of society and social interaction. Learning the subtle rules that help us function, and finding or imposing order. This is something we all go through, but in Sean's case he is also dealing with the physical and mental fallout of the aforementioned accident, his identity inextricably bound up in the suffering inflicted on himself and those near him.

When tragedy strikes, people scramble to find an explanation; a precursor or some kind of unheeded but retrospectively apparent warning. People fall all over themselves to blame culture for violent incidents: video games, music, larping, sexting, movies. A hand-wringing alarmist could find a dozen such cultural signifiers in Wolf in White Van - Conan and other fantasy novels, arcade games, Rush, religious pamphlets - but the point is that this is ridiculous. The thesis of Wolf in White Van is that sometimes, there is no reason. People can be inexplicable, their behaviour impulsive. They can’t always explain their motivation or justification. Life is absurd, sometimes cruelly so. Wolf in White Van, from the very first chapter, is consistent in its theme: there is no Why. There is no neat moral to be found at the bottom, and to search for one is futile, to paddle against the stream of inevitability.

This functions perversely to the form that Darnielle is working in. The structure of a novel promises resolution in the final chapter, the mystery revealed. But Sean pointedly hates mystery novels. Part of my compulsion to keep listening was to find the why, the reason. Despite being a bleak and unsettling piece of entertainment, I felt okay afterwards. I managed to let go of the need for a why. It’s a kind of catharsis, embracing the ‘shit happens’ outlook of the book. It’s also cathartic to realise I can ascribe the same reasoning to my own irrational, destructive impulses when I was younger.

Bless their diffident exterior – for young people everything is raw and unknown. Emotions are powerful and overwhelming and bizarre. Teenagehood is where you toughen and where you’re proved. Maybe you emerge with a forged shield, or maybe a pattern of scars. It becomes clear that two divergent voices in the book - adult Sean and teenage Sean - have very different ideas. The older narrator is able to control his anger and put other people’s feelings first. Unlike teenage Sean, adult Sean is compassionate and understanding, and more likely to think of others.

In tracing the steps from the young man Sean was to the present, the novel indirectly but inevitably addresses a number of mental health issues: anxiety, depression, impulsive and compulsive behaviour, suicidal ideation, morbid fascination, violent fantasy and the cognitive gulf between teenage thinking and adult (usually, parental) thinking. Satisfyingly, it doesn’t speechify about any of them, they hover at the edges, Serious Words for the fucked up stuff in our heads. Darnielle, as a former psychiatric nurse and former recreational drug enthusiast alike, is familiar with the behaviour of the mentally ill and the effects of antipsychotic medications. As a meditation on fucked up thoughts and impulses, it forced me to reflect on the dark urges within myself, and feel grateful that I have never acted on them.

Sean acted on an irrational, destructive impulse and lived, and he grew up. We all do things, small things, unthinkingly or for no reason. We might look back and concoct a reason, an excuse, the Why. This is normal. We learn that Sean did a big thing – in the end, in all honesty, he admits that he does not know why he did it. And that’s okay. And there’s a silver lining, an altruism. It was not expected that Sean would survive his accident. He not only managed to survive, but come to terms with who he was and lead what he considers a fairly normal life. At one point, required to give a statement in court, he explains that his games were only ever designed to bring happiness to others.

Like the Alpha cycle, the novel also ends abruptly, lingering briefly on small and ephemeral details. The ending, and novel as a whole, describe a fatalistic viewpoint, but it’s a fatalism with a space for hope, taking pleasure in the present moment.Postscript

The boxes of carefully stacked hardcovers hadn't reached these shores when I decided to review Wolf In White Van, so I experienced the novel as an Audiobook, read by the author himself. Darnielle also contributed musical stings to the voice recording, marking breaks in the text and underscoring the intensity of certain passages. For the first ten minutes or so I kept expecting to hear him break into tune. For me, the steady, downbeat voice and lyrical phrasing keyed into the Mountain Goats songbook, using reminiscent turns of phrase.

Darnielle’s familiar tone is punctuated by subtly different phrasing that accurately imitates the voices of teenagers, doctors, outcasts. I often find the pace of audiobooks frustrating, but in this instance it forced me to pay attention to and relish every sentence. As much as I love the Mountain Goats, I can only honestly consider myself a 4 or 5 on a scale of 1 to 10 compared to the unyielding devotion elicited from some of their fans. Even so, I’ve been kept company by Mr. Darnielle’s voice since I was 17 and it felt comfortable - almost directed at me, as egocentric as that may seem.

Wolf In White Van is available through Penguin Books Australia now.

See also:

BB for The Saturday Paper

Sonia Saraiya for The AV Club

Emily M. Keeler for The Hairpin

Wolf in White is also available as an audiobook from Macmillan Audio. Listen to an excerpt from the audiobook below: