Whose Values Will Prevail?: Kawerau, 1986

Helen McNeil on a flashpoint in industrial action, and the town that survived it.

In 1986, the industrious Bay of Plenty timber town of Kawerau weathered an 86-day strike that served as a flashpoint for the Aotearoa labour movement. Author Helen McNeil, who has just published a fictionalised account of the battle in her 'A Striking Truth', looks back on where things began to change.

Helen Kelly died on 16 October, 2016. She had been the President of the Council of Trade Unions for seven years, and a passionate voice for safety and justice for working people for her entire working life. These included forestry workers, the miners at Pike River, and those who would have otherwise been at the mercy of insecure zero hour contracts.[1] Her successor at the CTU, Richard Wagstaff, called her a ‘relentless change-maker’. More than that, she represented the power of the organised collective, speaking up against power.

The organised collective. Where is that now? The international protests after the election of Donald Trump were a short-lived collective, of sorts. Perhaps the disenfranchised blue-collar voters that helped make him President were too - time will tell. But where is the organised collective that grows steadily, with a purpose, unified over a long period of time? The one that stands up to power? And what replaces it in towns and cities where it has been destroyed?

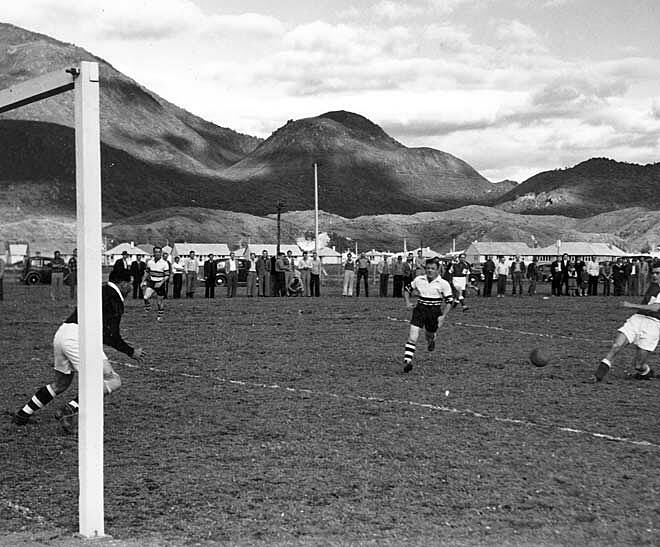

I grew up in Kawerau, a town that, for the last twenty years, has made the news because of suicide, unemployment and a shrinking population. In the 1970s and 1980s it earned a bad reputation as ‘Strike Town’. It only exists because the Tasman Pulp and Paper mill was built there in the 1950s to take advantage of the vast pine swaths of Kaingaroa Forest. Most of the townsfolk worked in the mill or in some service capacity. In its time, Tasman was the biggest pulp and paper mill in the Southern Hemisphere - in 1960, it was responsible for 20% of New Zealand’s exports. The company had its own fleet of ships to take the giant rolls of newsprint to customers around the world. It was a mill town, prosperous and proud of its identity. Workers flocked to the town for the high pay. Sons and daughters of those workers were ensured jobs, because Uncle Tasman looked after its own.

In 1962, when I was 10, the town was full of young men working to construct the second paper machine and to plant more pine trees. The new forest reached up the flanks of our mountain, Pūtauaki. We were proud of the boom town we were all building together. In 1970, construction on a third paper machine began. There were plans for a fourth, and for the town to grow to twice its size.

But trouble was ahead. From 1970 to 1980, New Zealand had the largest number of industrial disputes in its history. It was the zenith of Robert Muldoon’s controlled economy. To try and manage its international debt obligations, Muldoon’s government held a price and wage freeze in place from June 1982 until 1984. The economy, and people’s lives, were stagnating. When the freeze was lifted, angry workers countrywide went on strike, demanding more money. Labour stoppages, walkouts and strikes broke every previous record.

To understand those stoppages and strikes, it pays to understand a little of Aotearoa’s union history. Some unions were known for being militant. That meant that they refused to back down to government pressure, even when it came from the traditionally pro-union Labour Party. Members were often accused of being communist troublemakers (Helen Kelly’s father, Pat, was counted as one). Though their names have largely vanished from popular memory now amid various mergers and dissolutions, in the 1970s and 1980s there were still a few unions with a well-established reputation of being militant: the Northern Drivers, the Waterside Workers, the Tramway Drivers, the Freezing Workers, and one union from Tasman—the Northern Federation of Pulp and Paper Workers.

Because the town was small, it was often personal. By the 1985 strike, many rested blame on the intransigence of the Pulp and Paper Workers. They were the ones who held out- they were the militants that many feared were jeopardising it for everyone.

Tasman did not have one union for the whole mill, as industrial law required unions organise around their occupation (such as carpenters, engineers, or cleaners). Each had their own secretary and representation to management. There were around fourteen unions on the Tasman site. Often, union was fighting union for recognition of who was paid to do which task. It made for bad feelings between different workers.

At Tasman, there was a strike in 1978 and the mill closed for 35 days. Another one in 1983 lasted 50 days, and in 1985, the mill closed for 42 days. With each strike, there was further division between the supporters and the declaimers. Because the town was small, it was often personal. By the 1985 strike, many rested blame on the intransigence of the Pulp and Paper Workers. They were the ones who held out- they were the militants that many feared were jeopardising it for everyone.

I wrote A Striking Truth about the last big strike in 1986. It went on for 86 days. That’s nearly three months. Time enough for people to lose their houses because they couldn’t pay their mortgages, for businesses to go broke, for families to move away because they could not manage the instability. The strike, I believe, had a significant effect on the changes in New Zealand employment law five years later that further reduced the power of unions. In my novel, the characters are fictitious, but many of the events, fears, and tensions are not.

The strike started, ostensibly, because the management had employed a woman to work in the Chemical Preparation Plant. The Northern Federation of Pulp and Paper Workers didn’t like it. That’s what was reported, and widely believed. In an increasingly cosmopolitan country, this account caused considerable ill-feeling towards the Tasman workers. Walking off the job meant that the pulp digesters stopped cooking and there was no chemical slurry being carried along the belts. The spinning paper machines no longer sang their high-pitched note as they filled roll after roll of newsprint. The boats down at the Tauranga port eventually ran out of meaningful trade.

So what really set this strike off? Was it the prospect of a woman doing shift work with the men?

The union secretary at the time was John Murphy. I was unable to talk to him, but his deputy, Harold Appleton, who took over Murphy’s role towards the end of the strike, spent many hours with me, showing me his archives and talking through what he believed really happened. It was a privilege to be able to listen to his in-depth—and at times, emotional—account.

As it happens, the story of a woman in the Chemical Preparation Plant that the public was told was only a partial truth. One of the conditions negotiated by the pulp and paper workers was that the union should be consulted if a vacancy came up. The union saw it as an opportunity to discuss the skills needed and the obvious safety issues; management saw it as running a closed shop. Murphy was particularly suspicious of an un-notified request from management to train a new employee (who happened to be female) to work alongside unionised labour. He wondered, at the time, if it was a setup by management to undermine the union.

By 1986, the management of Tasman had changed. In the 1978 and 1983 strikes management had ultimately given way to the demands of the union. After all, Tasman had been established by co-operative effort of the then National Government and Fletcher Holdings. The style of leadership and organisation offered by both Sir James Fletcher and his son (James Jnr.) was that of a family business providing a job for life. In 1981, however, Sir James’s son Hugh took over and oversaw the amalgamation of the family’s construction concern Fletcher Holdings, Ron Trotter’s Challenge Corporation and Tasman Pulp and Paper to become Fletcher Challenge - which, by the early 1980s was New Zealand’s largest listed company. And it made it big on overseas stock exchanges, too.

Trotter was the chairman. He was also a member of the Business Roundtable, established to advocate for the extensive pro-market economic reforms then sweeping the country. The company had a bigger capital base it could rely on and, under Trotter’s guidance, the management of Tasman was directed to stand up to the unions.

Profits from pulp and paper production were cyclic—that meant there were good years and bad years. The accumulation of lost working days was not helping the balance sheet. By the time the last strike loomed in 1986, Tasman was in danger. Management took a hard line in response. They would modernise the plant by introducing more technology and, more importantly, reduce their labour force. The Pulp and Paper Workers held out against this—‘a job created was a job kept’, they said. It was a stalemate.

The CEO of Tasman at the time was Garry Mace. He was as generous with his time as Harold Appleton, and I spent a morning with him many years later hearing his side of the story. He maintained that the company would have gone bankrupt if they had given in to the union demands.

At the national level, the climate for unions was changing. Compared to its predecessors, the Fourth Labour Government did not have much time for organised labour. In a TVNZ Close Up programme made about the strike, the Pulp and Paper Workers Union was called a ‘dinosaur’. The family-managed model that Sir James Fletcher had established and his son continued was considered idealistic and impractical. The labour of a working person was now recast as a commodity, to be bought and sold at its individual value.

The strike ended in early October after the pulp and paper workers voted by a majority to return to work. There were a few difficulties with the return, but nothing instantly dramatic. Concessions, as such, were not made - a new model for disputes, proposed by a consultant who had worked with the Thatcher government after the UK’s miners’ strikes of 1984, was developed instead. Most of the unions, exhausted by the length of the action, agreed to it. The “Special Disputes Committee” would include three representatives from Tasman unions, and four from management. All issues, including the ones the unions would normally have handled, were routed through this committee. How long this committee was to stay in place was never clear - when the Edgecumbe earthquake happened five months later, everything changed again.

It now takes three workers in a computer suite to operate a paper machine at Norske-Skog (that is, the new Norwegian owner of Tasman Pulp and Paper). Once it took sixteen. It is doubtful that jobs will even exist for those disenfranchised blue-collar workers in the USA. Kawerau looks less like an outlier – the town that fought the loss of jobs and livelihood and lost – and more like the shape of things to come.

The 6.5 magnitude quake badly damaged the mill, though the old spirit of collective cooperation returned as Tasman’s employees worked long hours to restore the machinery and plant. In the wake of the disruption, the management’s promised reductions in staff were gradually put into place. Many people took redundancy, still others moved away, houses were left empty or sold very cheaply, businesses closed. The town’s decline had begun.

So what is the legacy of this ill-fated strike? It’s still a touchy subject in Kawerau. It seems to me that it also had a part to play in the sweeping changes to New Zealand’s labour laws, a scapegoat for reformers looking to hit union membership and density.

Ironically, the potential power of the unions increased briefly after the strike was broken due to the passing of the 1987 Labour Relations Act.[2] Despite the reservations of several pro-market Cabinet Ministers, the Labour government could not deny its deep connections with the labour movement. The shift of bargaining from a centralised system, which set a national award, to a firm or enterprise level meant that individual workplaces could decide on awards for workers. Union membership was still compulsory and it continued to be the union that represented the workers.

This all came to an end when the Fourth Labour Government was voted out in 1990. National won the election by a large majority and the end of unionism in Aotearoa as we knew it was effected by the 1991 Employment Contracts Act.[3] Its legislation did not use the word ‘union’, and allowed for any incorporated society or individual to take its place. It became illegal to give any union member preference in contracts or to require union membership in a workplace. Overnight, unions had lost their role, their voice and their power. From 1991 to 1995, union density nationwide almost halved.

Helen Kelly’s run as President of the CTU came from 2007 and 2015, a challenging time of both rebuilding and threat for the labour movement. The national centre includes both white-collar and blue-collar unions—the teachers and nurses as well as the carpenters and fast-food workers. Despite partial rollbacks of the Employment Contracts Act in 2000, membership in a union in Aotearoa remains voluntary. Withdrawal of labour, or strike action, used to be the iron fist of the union in its demand for jobs, working conditions and health and safety of its workers, but it is difficult to strike in New Zealand these days. There is always a group of people who are not unionised who will continue to work.

And what of the international scene? The term ‘precariat’[4] has been around for a few years, and has begun to blur the white-collar/blue-collar divide. It doesn’t matter what the level of your education is - job security is a thing of the past in a globalised, digitalised world.[5] Trump has promised jobs for the disenfranchised workers of the USA. The ones who have been put out of work by the exporting of manufacturing to developing countries where labour is cheap. He is promising American industries that employ American workers. I wonder if these jobs will materialise. Will there be investment available in an economy that is totally globalised? Will the public want to pay more for goods manufactured in the USA?

Perhaps the real elephant in the room is automation. It now takes three workers in a computer suite to operate a paper machine at Norske-Skog (that is, the new Norwegian owner of Tasman Pulp and Paper). Once it took sixteen. It is doubtful that jobs will even exist for those disenfranchised blue-collar workers in the USA. Kawerau looks less like an outlier – the town that fought the loss of jobs and livelihood and lost – and more like the shape of things to come.

Kelly believed that unions were about values, not membership dues. I’m left with this question—what does the new organised collective look like in the realm of work in a globalised, tech-centred world? Can the union movement rise to the challenge? More importantly, whose values will prevail?[6]

A Striking Truth by Helen McNeil is available from http://www.cloudink.co.nz/ or an independent bookseller near you.

Read Helen's 'The Town That Nearly Died - A Brief History of Kawerau" at The Spinoff.

[1] http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/opinion/77743295/putting-an-end-to-zerohour-contracts

[2] http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/unions-and-employee-organisations/page-7

[3] http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/strikes-and-labour-disputes/page-10

[4] http://www.noted.co.nz/archive/listener-nz-2013/job-insecurity-are-you-in-the-precariat/

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/09/business/europe-jobs-economy-youth-unemployment-millenials.html

[6] http://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2016/05/05/like-manufacturing-jobs-to-china-whatever-trump-says-mining-jobs-are-not-returning-to-w-virginia/#5ebe22a56f48