Where Our Bodies Begin and End

Georgina Langdon-Pole traces a representation of her uncle's life

As I entered the lounge, I was greeted by a looming figure in an antiquated frame. A Māori man adorned in colonial attire, the paint stained a blackish-yellow by years of cigarette smoke. For a moment, he gave it the air of a military service, of something like a ritual. Underneath the dusky painting, the floor splayed, cleared of its chattels. Colourful mats tessellated around an open coffin. Inside a man’s body lay vulnerable, immalleable. Cocooned in a stiff wedding suit, a pink flower cresting from the chest pocket and animating the stillness.

My family huddled around the casket – wailing, moaning, and collapsing at the edge. Now – my turn. “Touch his head”, said my mother. We lurched forward together, her hand guiding mine. I recoiled quickly, perturbed by the touch of his translucent, icy brow. I waited. Poised, for his chest to heave or his eyelids to flicker. The moment pressed on. Still nothing. “Where is he?” I probed. My mother offered me an explanation involving angels, spirits and other such effigies. I liked the sound of this. She was convincing, but I knew the circumstances leading to that moment couldn’t be undone.

By touching his forehead; feeling where his body ended and mine began, I straddled an ulterior line between life and death. Amid all the escalating possibilities of childhood, I was suddenly carried to life’s very periphery. Somewhere in that space between something and nothing, the world unfolded before me.

In her book Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, Hélène Cixous writes that the dead are our first masters. The man in the casket was my mother’s brother, Brendan Pole, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1991, when I was 7 years old. In many ways, his death gave me the world as I know it now, in all its lucent complexity.

During his illness, HIV was relatively new in New Zealand. The first recorded case was in 1984, a 30-year old gay man who had been living in Sydney and was transferred to New Plymouth to spend his final days with his family. Though community members had been working hard to raise awareness about HIV for some time, it was still veiled in misunderstanding, consternation and shame.

As children my brother Zac and I were impacted by the confronting experience of Brendan’s death. We also learnt about his struggles living with HIV and AIDS, and his journey coming to terms with dying. Stories recalled by our mother revealed elusive dimensions of the human condition we were each too young to have ever seen unfold: revealing intersections of identity, belonging and isolation. Of secrecy, pain and hope. Through his life and death, Brendan became our most ethereal teacher.

24 years later, Zac has illuminated Brendan’s journey in an artwork, My Body… (Brendan Pole) (2015). The work is currently being exhibited as part of a solo exhibition, Meine Bilder, at the Physics Room in Christchurch. It comprises a poem written by Zac, as informed by the testimony of our mother. It’s adapted from Brendan’s original, a poem he recited to her by heart shortly before he died. She recalls how the poem seemed a site of both refuge and resistance for Brendan; a coded response to his struggle with HIV and AIDS, and all that remained unresolved in his life until the end.

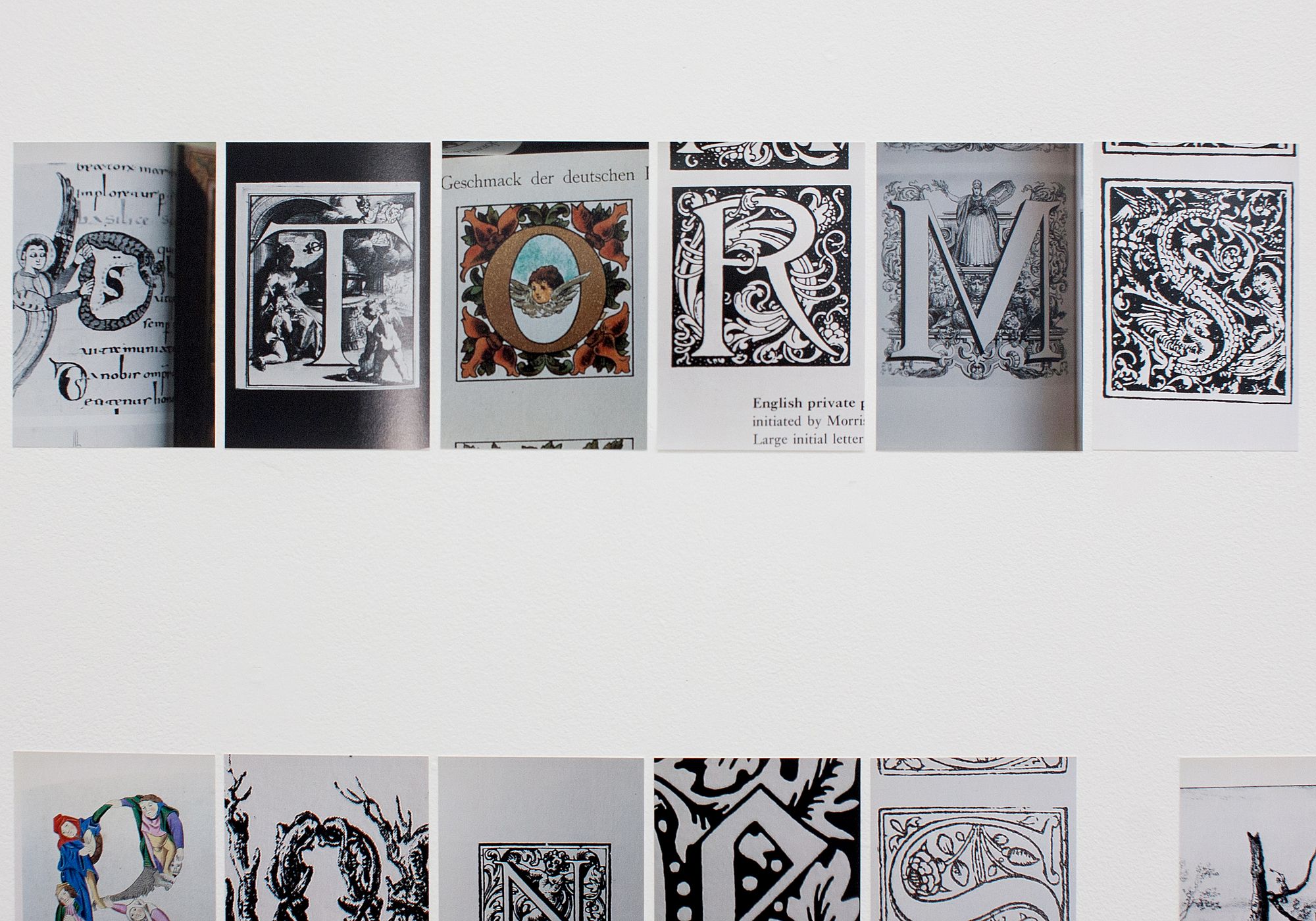

My Body… (Brendan Pole) evolved through two processes. Firstly, in the reconstruction and rewriting of the poem by Zac (which to his knowledge, was never written down). The second was the manifestation and display of the poem in relation to Brendan’s life. The poem has been presented using photographs of letters from Alison Harding’s Ornamental Alphabets and Initials (Thames and Hudson, 1984). Harding’s work, now long out-of-print, is a visual and historical overview of ornamental typographies from largely Christian religious texts spanning over 800 years.

The piece oscillates between the past and present, the personal and the political. The poem is a deeply intimate reflection of Brendan’s life and his struggle, a loss (like any loss) that feels current when we trace the shape it left behind. But it also grapples with the complex histories and elapsed moments which fundamentally shaped Brendan’s identity – diverse expressions of the self, battling with repression as an internal and external process. *

Brendan was adopted into our family from the echoing, polished rooms of the St Vincent’s Home of Compassion in Herne Bay in the early 1960s. Busy Catholic nuns in stiff cotton headpieces click-clacked the corridors in functional black shoes, tending to unmarried mothers and their babies from ward to ward. There, in a room ordered by rows of discrete white cots, Brendan rocked back and forth obsessively – as if in fast-forward prayer, as if his repeated swoops would carve out a route back out of the light and cold, back to his mother.

It was a time when having a child outside of wedlock was frowned upon. Adoption was commonplace, and the prevailing ideology was that it should be a complete break between biological parent and child, enabled by state legislation. Veiled in secrecy, pregnant women were garnered into institutions and encouraged to put their past behind them. This was, for many, an alternative to the stigma and hardship that came with overstepping social taboos. For reasons that remain opaque, Brendan was adopted from both his birth family and his culture, crossing ethnic borders from a Samoan to a Pākeha family.

What we do know is that while she was a volunteer at the Home of Compassion, our grandmother formed a strong bond with four month old Brendan during her days of service. A decision was soon made that he would become a part of their large and expanding family. Brendan was brought up and schooled in the Catholic faith, and a number of challenging times in his life, he continued to seek the support and guidance of the Church. But he also found a strong affiliation with Māori – he trained with a Māori organisation when he left home, and then he met and married a Māori woman.

“Perhaps it was the focus on identity and whakapapa,” my mother surmises now. “Something he himself was broken from, and always wanted to uncover. Or maybe it was the welcomeness he found in the people, a sense of belonging he often struggled with. Whatever it was, it touched him deeply.”

It was perplexing for some that having crossed borders once, he should seek comfort in a different culture again. But it was that balancing of different lives and identities which made him who he was. Brendan reconnected with his birth mother not long before he died – something he’d always ached to do. Having done this, he faced his death the way he lived - balancing complex ways of believing, communicating and being.

*

We all face that complex balance, even if we’re used to negotiating it from years of practice. All sorts of forms and customs have been used to communicate beyond the limitations of our time and place. More than any development before or since, the expression of stories and ideas in Christian and Western histories remains dominated by the advent of written text. Its everyday use exploded with the invention of mechanical movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440. This sparked the printing revolution, heralding the rise of mass reproducible communication.

The reproduction of written text occurs with ease on a mass scale. It is by nature externalised and produced outside the human body, and now co-exists with traditions of oral recital and inter-generational storytelling, which have and continue to play a fundamental role in cultures for which the written word was a late, colonial arrival. In these contexts stories are carried through the body, and are often used to illuminate the inseparability from one generation to the next; the oneness of the living and the dead. They have impacted not only the way in which information is carried in these cultures, but also on the way people organise their lives and create meaning in the world.

In this sense, My Body’s central concern is a 25-year-old act or performance, embedded in the memory of our mother. By speaking at length with our mother about Brendan’s life, his identity, struggles living with HIV and AIDS, and his death, Zac’s subsequent reconstruction and re-authoring of the poem tests the limits of intergenerational memory. The use of spoken word resounds Brendan’s beginning, and of the Samoan oral culture he was torn away from – a culture that relies on acknowledgement of the past, as a means to live in the present.

In our present, the poem’s displayed in illuminated, elaborate typographies. In this sense, it’s tying itself to early Western written culture, and in particular those texts which held a didactic purpose in the history of Christianity. The seductive and luring detail of the letters, often made in gold leaf, were used to place emphasis on the sacred nature of religious texts, and to amplify their importance.

Zac’s repurposing of this form becomes in itself a transgression of the belief systems and boundaries which presided in Brendan’s life. The very systems of belief these letters were created to proselytise obfuscated his identity time and again – now, they’re used to tell stories and convey meaning they once hid.

*

The period from 1985 to 1995 marked the rise of the HIV epidemic in New Zealand. Early on, little was known about how HIV was transmitted. There was no known cure, and a lot of panic. This resulted in cycles of misinformation and fear around its transmission.

Because HIV can be transmitted through unprotected sexual intercourse, the narrative around the new disease fed into dominant values and discourses around what were deemed ‘deviant’ forms of sexuality and behaviour. Homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity (particularly among women), and even sex out of marriage were already condemned by mainstream society, and so narratives that the infections were the result of personal irresponsibility and thus a form of punishment, thrived during the first and worst outbreak of the epidemic.

Inevitably, the level of imputation and shame involved sanctioned a veil of secrecy around HIV prevention and treatment. The compounded discrimination and stigmatisation of those who were HIV positive (or simply profiled as being HIV positive) put people off getting tested and accessing appropriate care and support. When Brendan got sick, even the officials asked our grandparents to keep up the charade, as our mother recalls.

“When we first found out that Brendan had HIV, the doctors advised Mum and Dad to tell their friends and community that he had cancer,” she tells me. “Not only were they facing the loss of their son, but the thought of having to lie about his death was daunting. I think the secrecy around it was deeply hurtful for Mum and Dad. Society didn’t accept it, so how could they find the space to come to terms with it? I’m not sure they ever did.”

The challenges Brendan and other HIV positive New Zealanders faced in telling their stories reverberate in My Body’s camouflaged display of texts. The letters of the poem are intricate and detailed. The letter O is flanked by decorative bursts of red flowers and encircles a tiny cherub angel at its centre. The letter M is constituted by the muscular legs of a man, splayed open and vulnerable.

The text and poem become a puzzle the viewer has to decipher. The viewer’s experience in the duration of the work; the time it takes to read the poem and to locate the words, echoes our struggle as human beings to tell the truth through language. Finding the words has always been an effort.

The work’s ongoing reconstruction of Brendan’s story and re-appropriation of language, places emphasis not only on the capacity of language to silence, but conversely, the power it also holds to transform the way we live in the here and now. At a pōwhiri, Māori recite their whakapapa to acknowledge the series of people and moments which led up to the present. It is through this utterance; an acknowledgement of the past and a marking of difference, that one can activate the present. This idea is embedded in what philosophy of language calls “performative utterances”. These are used to describe forms of language which are not simply describing reality, but also charging and moulding the social reality they are defining.

Through a series of legal fictions and verbal euphemisms, swathes of Brendan’s short life were a reality constructed without his input. The Adoption Act 1955 stated that he was our grandparents’ child “as if born to that parent in lawful wedlock” - another past, another geneology voided. But in facing his death, Brendan began to unravel his identity on his terms, by meeting his birth mother, immersing himself in tikanga. Through this journey, the languages and rules of law and religion, which had always been so definitive in his life, loosened their grip. In his journey towards death, language seemed to become a space where he could resist what had been enacted upon him.

Many artists have explored the idea that we all inhabit, in some way or form, a secret life. A space where we can exist beyond the confines of ‘true’ or ‘false’. But also, beyond what we might be able to grasp or understand. For many, language and art are sanctuaries where we can live out our secret lives. Where we find truths and meaning, which are stilled and repressed. The poet, Anne Sexton, thinks of form as a kind of magic for discovering the truth. She explains: “I’m hunting for the truth. It might be a kind of poetic truth, and not just a factual one, because behind everything that happens to you, every act, there is another truth, a secret life.” With days to live, Brendan spoke that content of his secret life to my mother.

He was fed up with the monotony of his bed and the four enclosing walls of his bedroom, and so our parents clambered him into their van and drove west to Māori Bay. He was emaciated and exhausted, and struggled to move his body. They took everything out of the back of the van and put a mattress in for him instead. Resting on the makeshift bed and framed by a rusting metal wagon, my parents backed up the van onto the cliff top. Craning their necks, they glimpsed out over the surging West Coast swell and pale grey sky. Brendan recited his poem.

That gap, of conjectured moments left incomplete, that constant currency of loss and grief, is why there is nothing more plaintive than the death of a young person. Brendan died when he was only 28 years old. He, like so many others, was silenced in life and in death. Perhaps the most elemental premise of Zac’s work, and indeed as I write this, is to ask what we - the living - can do for people who died in the face of seemingly insurmountable pain. How can the living resound stories suppressed and untold? How do we become companions of the dead?

Brendan was scared that he wouldn’t be remembered. Language gifted him, at that moment, the means to carve out a space of resistance and acceptance. His act, his utterance, urges us to consider how we can manifest something out of nothing; how we can carve space for hope amid great suffering.

In exploring language as a site of refuge and resistance, Zac’s work inevitably becomes the very hope it explicates. Straddling a line between something and nothing, the work becomes that ‘something’: a memory, a tribute, an act of solidarity. Brendan’s poem propels stories and meaning beyond the confines of what might be accepted or denied. Beyond the limits of the living and the dead. Of where our bodies begin and end. In this way, Brendan has taught us how to live. In doing so, he has gifted all of us, the world.

My body

A clot

Of inscriptions

Flayed by

Sacred hunger

Clinching nothing

Where paradise

Storms

Bones kiss

Sour air

And undo

The folded lie

This dirt

These trinkets

Hollow siren songs

Will not contain

Such blessed

movement

This language

Of virus

Oh heap

And thrust

Nothing is decided

But is told

By the light

Of the axe

In my secret life

I am

with him

Brendan Pole

My Body (Brendan Pole) is showing as part of Meine Bilder at The Physics Room, 209 Tuam Street, Christchurch,from 19 January to 30 January 2016.