What's up with Housing?

For whānau living in cars, the arts sector may as well be on Mars. Ataria Sharman explains what is wrong with housing, and how this affects diversity and representation in our arts communities.

A few years ago my sister, her partner and I were doing the rounds of the Open Studios art event in Whanganui. It’s a yearly affair, where local artists open up their studios to the public to visit and peruse what the artists have on offer. As I surveyed the inside of an expansive industrial building off a main road, filled with art made from repurposed driftwood, I considered the cost of renting this studio space on top of an artist's living costs like rent or a mortgage. It made me think of the possibilities for artists when living costs aren’t through the roof. Whanganui has some of the most affordable houses in Aotearoa, with a median house price of $470,000 (although this median price is a massive jump from when I was wandering around the studios, considering they’ve gone up 17.5 percent in the past year). At the time, my sister and her partner were renting a privately-owned, ex-state house, a little three-bedroom home, for just over $200 a week. It was cold, the decor old, it was near an industrial area, but their rent was affordable in a way that mine wasn’t in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. The kind of rent that would enable an artist to work part time instead of full time, and even afford to rent a studio space.

Housing at the moment is a hot topic. Everyone is clamouring to cover the issue of ever-increasing house prices. But what does an increase in house prices actually mean? Extraordinary house prices for the most part mean high debt. Larger debt (particularly if interest rates go back up) increases weekly mortgage payments for either homeowners themselves or landlords, who then pass that cost on to renters. We know the more whānau spend on housing the less money they have left over for everything else. If the cost of housing was reasonable, and affordable, whānau might have the time to think about spending their disposable income on things like painting supplies for their kids or the cost of the bus fare down to Te Papa. If whānau were not just surviving the day-to-day, if there was a roof over their heads, food in the cupboards and petrol in the car, they might actually have the energy to take up that craft hobby, or even volunteer on their local arts community board.

The point I’m making here is that housing, as part of a wider unequal system, influences our arts sector. Access to housing, safety, security and a disposable income determines who has the time to sit on our governance structures, our creative boards and community groups. Whānau who are living in cars are not even remotely thinking of the arts – the arts sector may as well be a colony on Mars, that’s how ridiculous it seems to visit an art gallery when you don’t know how you are going to feed your children. A system that is okay with whānau not having security of housing is the same system that also decides who is creating art and who is enjoying our art, buying our art.

Add a sprinkling of conscious or unconscious bias planted by the deficit-thinking machine

Who are the renters and who are the landlords? We know that in the 2013 census, 56.8 percent of Europeans owned their own home, contrasting with 18.5 percent of Pacific, 28.5 percent of Māori and 34.8 percent of Asian people. It’s hard to grasp the gravity of this until you realise that if you are European you are three times more likely to own your own home than someone of Pacific descent and two times more likely than someone who is Māori. Reverse these figures to reflect those who don’t own their own home and the data is desolate. Where only 43.2 percent of Europeans don’t own their own home, make that 71.5 percent of Māori and 81.5 percent of Pacific people. Clearly this highlights racial inequity in our housing system. We know that Europeans are more likely to own their own homes and therefore have security of housing and place.

The reality is that those who have the influence over who can or can’t rent a house – landlords – are more likely to be European. Add a sprinkling of conscious or unconscious bias against Māori, Pacific and other minorities, planted by the deficit-thinking machine that the Stuff Apology to Māori has more recently called attention to (I once questioned why I myself wasn’t in prison, after being repeatedly told the damning litany of statistics on Māori), and the monster of a two-pronged disadvantage for minority groups seeking their human rights to safety, security and shelter looms overhead. Is part of our problem with home ownership a grapple with a class system, or an unspoken caste system – the bottom rungs of which include Māori and Pacific? The book Caste,by Isabel Wilkerson, describes it as “the infrastructure of human hierarchy, the subconscious code of instructions for maintaining [in the case of America] a four-hundred-year-old social order.” Could scrutinising our current housing situation be a starting point towards uncovering our own architecture of human hierarchy here in Aotearoa, the infrastructure of our own divisions?

I spoke to a single mother. Her rental had been put up for sale by the investor who owned it, and she’d kindly agreed to let a real estate agent walk us through her house. This was a couple of years ago, when my Pākehā partner and I were buying our first home, on the outskirts of Te Whanganui-a-Tara. We were looking at houses right across the region, from Waikanae to Stokes Valley. Prices were spiralling out of control in some areas, and landlords were cashing in and selling their rentals. The mother told me she was worried. In the 42 days that the landlord was legally required to give her as notice before selling, she hadn’t been able to find another rental she could afford. She didn’t want to take her kids out of their school zone, but felt that very soon she would have no choice.

His cheating left me with a tax-free gain of $15,000 – $5,000 for each month we owned the house

I lay there on a black rug, curled into a foetal position, eyes swollen, after watching the news, lamenting the increase in house prices in the market we were trying to buy in, while also sitting with my own privilege. The privilege to actually have a house deposit and, more basic than that, the privilege of even thinking that owning a house was possible. And yet I lamented because the housing market at the time was increasing $10,000 a week, and I knew there was no way we could possibly save enough to match the weekly price increases. I wondered how a system like that could be possible, let alone fair.

We eventually did buy a house. We’d been there a few months when my partner went overseas and met another woman. They wouldn’t stop messaging, which was annoying and unfortunate, so we split up. I didn’t have the means to buy him out, but his family helped him to buy me out of the house. At the time, I was devastated. I’d finally had a house, and his philandering and familial privilege cast me out. But it turned out that in a period of three months, the house had increased in value by $30,000. In order to buy the property off me, my ex-partner had to pay me half of the increase in value over the three months – $15,000. This didn’t include the deposit I had paid to buy the property, which I also received back. In short, his cheating had left me with a tax-free gain of $15,000 – $5,000 for each month we owned the house.

This personal gain of mine speaks to part of the problem with housing – what is good for one side of the coin is bad for the other. People with class privilege don’t seem to want to talk about this. What is bad for those who don’t own property (rising house prices), is a seriously good thing for those who do. I mean, no one in Aotearoa would say no to winning the lottery, and your house going up in value $50,000 or $100,000 in a few years is essentially doing that. You’ve won the housing lottery! And just like the actual lottery, in most cases it’s completely tax free! Even better, not a single day of work is necessary to achieve these earnings if you buy in the right place at the right time. I didn’t do anything to make that $15,000 except put in a vegetable garden. I think we can bust the myth that those who’ve made their wealth from property are there because they ‘worked harder’. It’s not about working harder, it’s about who can access additional lending from the banks to invest in the housing market in the first place.

The water would come back up the waste pipe into the shower tray, and the toilet wouldn’t work

The low interest rates we’ve got at the moment mean that those who can secure more lending from a bank can invest in housing and pay less on the interest repayments on their mortgage. Interest rates were lowered to stop mortgagees from defaulting on their home loans during the Covid-19 lockdown. These same low interest rates are also the reason why more money from banks has been entering the housing market post-Covid, because low interest rates also mean lower interest repayments, which over the full term of a 30-year mortgage can save you a lot of money. But the question we need to ask ourselves is: who are the people who have the ability to access more lending from the banks and take advantage of the low interest rates?

Last year, my new partner and I got into some serious trouble with housing. I’d moved to Whangārei, and we’d been staying at his mother’s place until she and I had an altercation. She’d kicked me out the week before my partner was moving to Auckland for 20 weeks of full-time studies, where he would also be paying rent. My partner’s good friend took me in and I moved into his whare in Otangarei. Now Otangarei doesn’t have what you’d call ‘a good rep’. I soon learnt that even mentioning you live on certain streets, at certain addresses, will raise the blonde eyebrow of a receptionist.

But what really got me was the state of the privately owned rental he (and now I) was living in. There were holes in the floor and large gaps between the floorboards, which had previously been covered by a carpet that the landlord had at one point removed, and then just thought – meh. The deck railing was broken – a real safety hazard. When you used the shower, the water would come back up the waste pipe into the shower tray, and the toilet wouldn’t work. You’d have to stick your hand into the cistern and pull the plastic mechanism, and even then sometimes it wouldn’t flush. It was a harsh lesson, and it taught me the privilege of being able to easily shower in the morning before going to work, the privilege of being able to flush a toilet after you’ve used it. And our friend, instead of asking the landlord to fix these things, would ring a plumber, and pay for it himself.

Then maybe we will see our arts sector start to reflect the diversity of our communities.

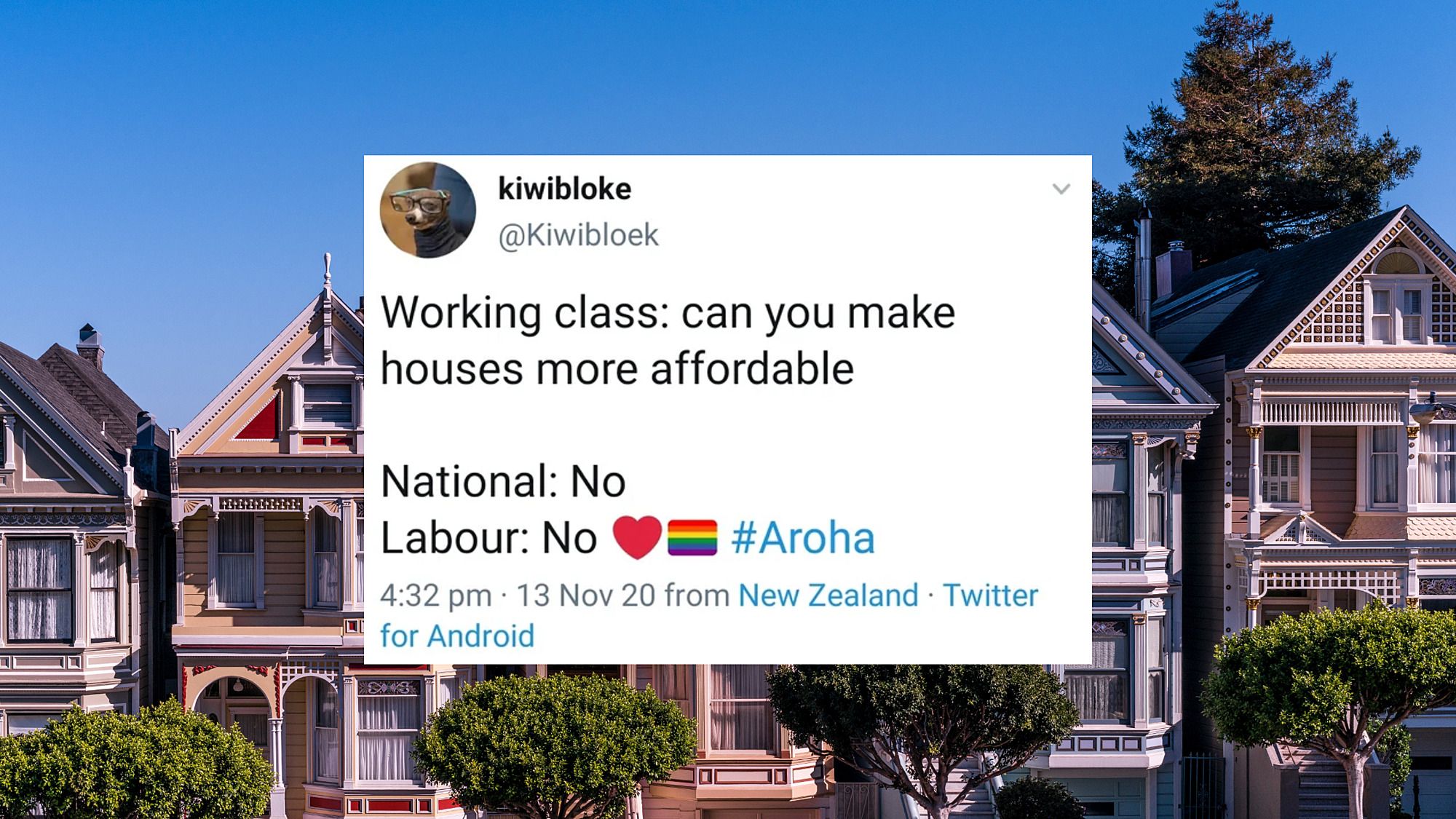

An argument I’ve heard used before, and not just in relation to affordable housing, is “well, if they have a problem with it, why don’t they just vote?” During the time that my partner and I didn’t have our own place, our letters were going to my mum’s in Te Whanganui-a-Tara and his mum’s in Whangārei, and many didn’t make it to us, including electoral letters. The thing about voting that anyone who’s always had a roof over their head may not understand, is that it’s actually super hard to get sorted when you don’t have a stable postal address. And imagine if we didn’t have the stability of parents who own their own homes, where we could get our letters sent to? You wouldn’t get the reminders, the electoral updates. It’s a moot point really, though, since Labour and National have said they won’t adopt any of the recommendations on capital gains taxation. But the idea that the government would implement a capital gains tax if more voters wanted it is unrealistic because it doesn’t take into account all the barriers to voting, such as insecurity of housing and the stresses of surviving day to day, that hold people back.

As it happened, this year we were lucky enough to secure our own place. We went under contract on a little whare 20 minutes out of Whangārei in the weeks just after lockdown and became part of the 28.5 percent of Māori who own their own home. So by the time the election rolled around, we were moved in. We got up in the morning, had some breakfast and wandered down the road to the local shops to vote. Now think about a whānau living in their car. They aren’t worrying about voting, they might not even know the election is on, or have received their voting cards or reminders. They might be thinking of the next place for the children to shower and whether they can afford to buy food today, not whether to vote red or blue or green or yellow or purple.

I acknowledge my own privilege and right now I’m using this privilege, the roof I have over my head, the kai I have in my belly and the position I’m in as editor of an arts journal to speak out. All of these provide me with both the energy and time to write this article, and a platform on which to share. It’s up to us, those on the other side of the coin, to really care about uplifting all those who aren’t. More whānau in the safety and security of a warm, insulated house – without overcrowding – is a win for everyone. There is no downside to whānau having more disposable income to spend quality time and do the things they want to do, rather than surviving from day to day. And only when whānau are not simply surviving can they think about learning, creating and maybe choosing to join our arts communities. We need to stop wanting to win the lottery just for ourselves and start to think about winning the lottery for everyone, Pacific and Māori in particular, and put the pressure on our decision-makers to do the same. If you do have a roof over your head and food in the cupboards, now is the time to use that privilege for good and to take real action to ensure all other whānau have access to the same. Then maybe we will see our arts sector start to reflect the diversity of our communities.