A Whakapapa of Exchange: A Review of Ngā Hokohoko

Contemporary jewellery practice in Aotearoa has a rich history of exchange between Māori and Pākehā. Ana Iti responds to this in a review of Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse.

When thinking about the title Ngā Hokohoko, the first image that comes to mind is an iconic watercolour illustration by the Tahitian navigator Tupaia, painted during his time on Captain Cook's first voyage between 1768 and 1770. It is Tupaia’s only known painting of Aotearoa. In the image, a Māori man wrapped in kākahu holds a string in one hand, bound to the body of an orange kōura. He presents it to a Pākēha1 man in a sailor’s uniform, presumably Joseph Banks. In return, the sailor holds out a bolt of white cloth. At the centre of the composition are four sets of hands and the things they hold. The bodies of the Māori man and the sailor are arranged in profile facing each other, kanohi ki te kanohi.

This is an image of exchange. From the early encounters between Māori and the Cook expedition observed by Tupaia, we know that the path to trade was preceded by miscommunication, kidnapping and murder. We know, as well, that value is cultural and contextual. Not all exchanges are equal and when it comes to barter or trade one or both parties stand to lose. Conversations around value and preciousness play an established role in contemporary jewellery practice and discourse in Aotearoa.

Ngā Hokohoko is an exhibition that gathers a group of contemporary New Zealand jewellers to explore a culture and history of exchange in Aotearoa that has been fostered within the jewellery community. Curated by Gina Matchitt (Te Arawa, Te Whakatōhea) as the culmination of her Blumhardt Curatorial Internship at The Dowse Art Museum, it includes work by Pauline Bern, Matthew McIntyre Wilson (Taranaki, Ngā Māhana, Titahi), Neke Moa (Ngāti Kahungunu, Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Porou, Tūwharetoa), Alan Preston, Joe Sheehan and Areta Wilkinson (Kai Tahu, Kāti Mamoe, Waitaha). These makers are linked by many strands; in many cases they have previously exhibited together, mentored or learnt from one another.

Not all exchanges are equal

I come to Ngā Hokohoko with that thought in mind. That the artists’ relationships link them together like a sort of whakapapa. I often think about the importance of placing myself within a whakapapa of contemporary art practice and have made time to connect with the whakapapa of contemporary Māori art. That is the lens through which I approach this exhibition. When people say whakapapa is everything, they mean it literally. Everything has whakapapa. Ani Mikaere talks about the way whakapapa is used as a method to gather knowledge, and puts it in this way:

Whakapapa encourages us to regard wisdom as cumulative, each tier building upon the layer before it … each generation takes the knowledge acquired by generations past and develops it further in light of their own needs and understandings.2

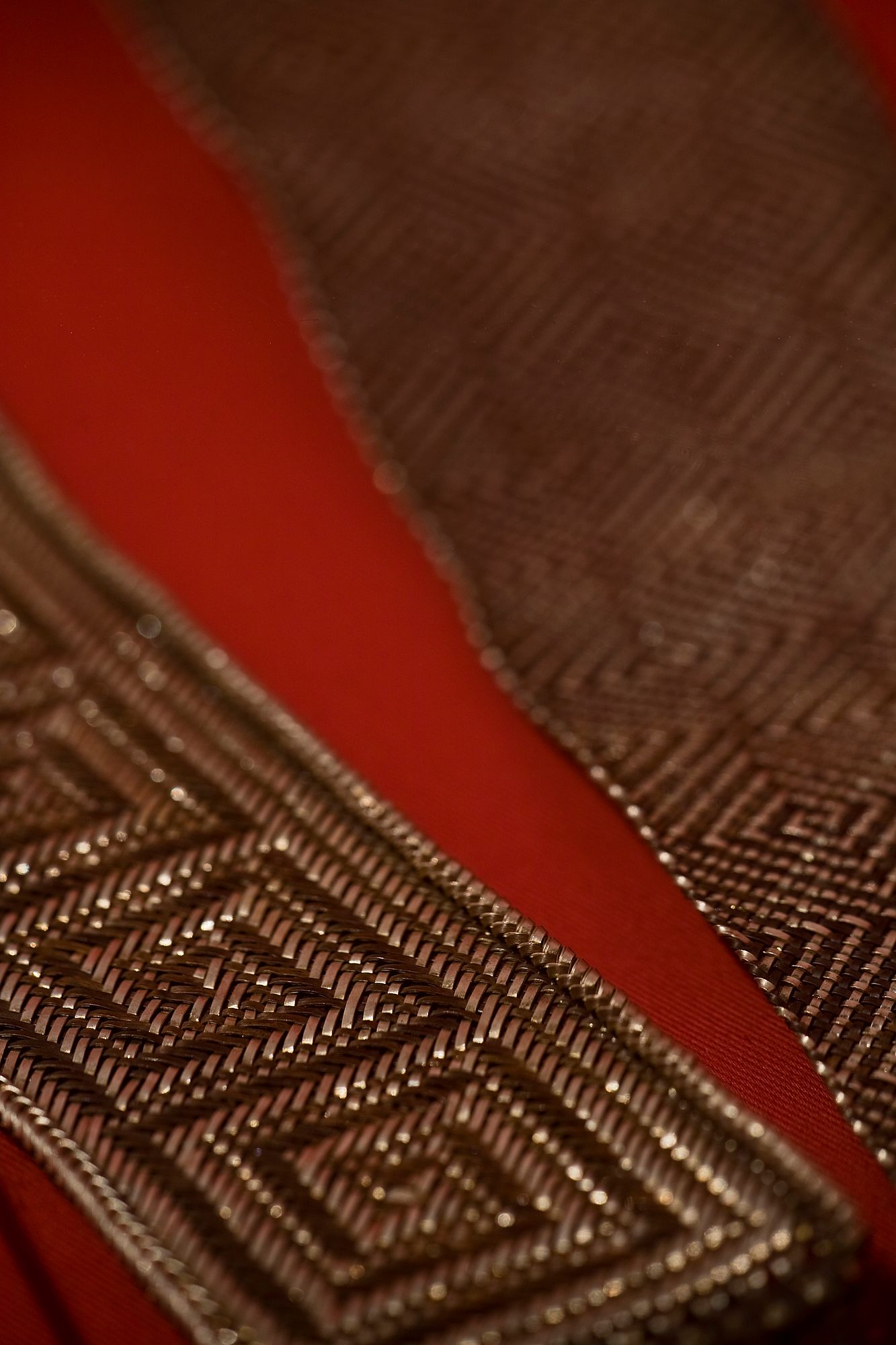

Hokohoko, like many words in te reo Māori, is also layered with different meanings. It supports the conceptual framework of this exhibition in its meaning to trade or exchange. Another interpretation of the word is to alternate. This meaning is folded into the exhibition design, with an alternating red, black and white colour palette, and triangular display cases that reference the geometric and knotted designs of tāniko. This is significant when thinking about Matchitt’s curatorial framework. Within tāniko, change occurs at different meeting points, as strands are woven together. Many of the works in the exhibition deploy materials including pounamu, silver, gold, shell and coins, that speak to the complexities of trade, resources and meeting points between people in Aotearoa. Together they develop tension, discomfort and appropriative tactics, the significance of relationships and previous exhibition histories. In this way, Ngā Hokohoko builds upon a whakapapa of exchange.

Matthew McIntyre Wilson, Tatua, 2017-18. Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse, 2020

Joe Sheehan, Reserve, 2013. Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse, 2020.

In The price of change (2012) Matthew McIntyre Wilson has harvested imagery from the coins of New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the Cook Islands, collaging them into a constellation of brooches. Many feature the carved koruru found on the New Zealand ten-cent piece, a generalised and non-regionally specific version of a koruru, designed by Pākehā designer Reginald George James Berry. In McIntyre Wilson’s brooches, this same koruru is extracted and fused with other iconographic components – and by inference the image of Queen Elizabeth on the back of the coin is destroyed. One koruru is crowned with a garland of ferns, another features the word ‘crown’ above with an image of a crown hanging below, and one wears the Endeavour as a hat. This act of reconstituting – and recontextualising – elements of coin design draws us into thinking more deeply about the significance of the design components themselves, and our relationships to the things they represent.

McIntyre Wilson’s other works in the exhibition are a collection of traditional Māori weaving forms rendered in unconventional materials, mostly precious metals. It's clear that McIntyre Wilson has an interest in the tension between material and contextual worth, seen in the action of increasing the value of ten-cent coins by destroying their function as one kind of currency and turning them into a cultural commodity like jewellery. But it can also be observed in works like Gold Kete (2018), a tiny kete woven out of 24-carat gold. Due to its smallness the supposed ‘function’ becomes speculative. Here the carrier for a precious taonga becomes the taonga itself, which leads me to think about the significance of the vessel, the things that carry our precious things.

*

Before I take the ferry journey across Raukawa, I always question what to take with me and how best to carry my possessions. Raukawa is the body of water between Te Wai Pounamu and Te Ika-a-Maui, more commonly known as the Cook Strait. I have made this journey many times. When I think about McIntyre Wilson’s artworks, I’m reminded of the ‘pressed penny’ souvenir machines sometimes found on board these ferries. To get your memento, you slip the copper-coloured ten-cent piece into one slot and the two-dollar fee into another. You then press a button to activate it. The mechanics are concealed in the body of the machine, but both the faces of the Queen and the koruru are pressed tightly between two plates of a mould and erased, transformed into an elongated coin bearing the image and name of the ship that carries you.

*

A series of sculptures by Pākeha artist Joe Sheehan, titled Reserve (2013), explores value from a different perspective. Sheehan’s work with pounamu is an almost compulsive exploration of the stone. He pushes the limits and imagination of what can be or should be done with pounamu, and is specifically interested in Pākehā relationships to this taonga. Reserve comprises six seamless ingots, some made from nephrite of New Zealand origin, and some from Russian and Canadian origin. On the one hand, there is a sensual joy in the materiality of this work, seeing the varieties of colour and grain within the stone and enjoying their finely crafted forms. Lurking behind joy is an uneasy feeling. What does it mean to create perhaps the ultimate symbol of capitalism and Western values that have led to the systematic oppression of Māori, in a material that is so highly valued to us? This seems to be the intention of the work, to evoke the messy thoughts and feelings about the relationships between Māori and Pākehā, a throughline in the curation of Ngā Hokohoko.

Sheehan’s work with pounamu is an almost compulsive exploration of the stone

The only ornamentation on these ingots is a carved ‘G’ followed by a series of numbers, mimicking the serial numbers used to authenticate and identify the place of origin of gold bars. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu are the kaitiaki and legally recognised protectors of pounamu in Aotearoa. Because this is a finite precious material that is valued culturally, spiritually and monetarily, there is also a system of authentication when it comes to its use. Maybe the source of discomfort when viewing Sheehan’s work actually comes from me, the lay person looking at Reserve who is unable to differentiate between which is the material with whakapapa to this whenua and the body of ancestors here, and which is the import?

Neke Moa’s work provides a counterpoint to Sheehan’s, both physically – situated directly opposite his work in the installation of the exhibition – and conceptually. Moa’s use of pounamu comes from a spiritual and cultural connection that is both physical and metaphysical. Ngā Hokohoko includes three of Moa’s works: a grouping of pounamu forms, Mauri Stones (2017), whose subtly placed holes and smooth contours speak to a potential but unrealised purpose of being worn against the body. Rongo (2015) is named after an atua of peace, a pendant whose form has been guided by the character of the stone. It looks liquid and almost molten. The surface of Rongo has been incised with a series of ring shapes, some painted in red, that recall the precious kokowai or red sealing-wax rimmed eyes of some hei tiki. The third is a pendant titled Naumai, Welcome to Māoriland (2012) and is a silhouette of a head and shoulders cut out in solid pounamu. However the silhouette is not complete, cut from the centre is the outline of a hei tiki, an unintentional inversion of McIntyre Wilson’s brooches. Perhaps the missing hei tiki here is a loving remembrance for the misappropriated form that has been commodified and mass-produced into cheap plastic trinkets.

Pauline Bern is one of the rangatira in this exhibition. She is a senior jeweller and has been an influential teacher and mentor to many contemporary makers during her time teaching at Unitec. It makes sense for her work to be situated physically as a central pou to the exhibition. Bern’s work is notable for its playful, inventive nature. This can be seen in works like Mend (2009–2019), an accumulation of shells and buttons that are subject to different forms of repair or modification and The Ring Project (2006), a collection of experimental rings by Bern.

The ad hoc nature of The Ring Project is balanced by the close attention paid to, and elegance of, their fixings. For this collection of jewellery, Bern used her immediate environment as a resource, collecting fragments of the mundane detritus around her and then crafting these components into rings. The materials used include chunks of sea glass and ceramic, cut sections of pōhutukawa twigs, various types of commonly found stone and more. This approach to material stands out in Ngā Hokohoko, and represents a pragmatism that has a strong place in Pākehā identity, the idea of making do with what’s around or a so-called sense of ‘Kiwi ingenuity’. This pragmatism was formed by a sense of remoteness or physical distance, the idea that Aotearoa is far from European cultural and economic centres. Where many of the other works in the exhibition draw on Indigenous material or forms, the humble nature of Bern’s points to a considered, ethically minded and very Pākehā approach.

Alan Preston, Pāua Chain, 1994. Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse, 2020.

Areta Wilkinson, Hine- ahua and Huiarei, 2013. Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse, 2020.

Pauline Bern, Carapace, 2015. Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse, 2020.

Alan Preston’s works in Ngā Hokohoko convey a whakapapa of influence that Pacific material culture has had in Pākehā jewellery practice. Matchitt situates Ngā Hokohoko in relation to a history of exhibition making and discussion around this topic. She references exhibitions such as Bone (1981)and Pāua Dreams (1981) held at Fingers, precursors to the later Bone Stone Shell(1988), commissioned by the Ministry of Foriegn Affairs and Trade, all of which featured Preston. His works in Ngā Hokohoko, ranging from the 1980s to 2019, exhibit a shift away from traditional Western materials to embrace Indigenous and local materials. Thisincludes two breastplates exhibited in Bone Stone Shell.

In the original exhibition catalogue Preston’s written contribution states: “I give thanks to the people of the Pacific and their ancestors. Their traditions together with mine are a source of ideas and inspiration for my comments about a new Oceania.”3 When looking at these works through the lens of current conversations around appropriation, they are difficult to grapple with. In the same historical context, the exhibition of these works was originally Pākehā-centric. Only one Māori artist was involved in the important national group exhibition Bone Stone Shell, exploring contemporary material culture at the time, but these are not new criticisms or observations. When Bone Stone Shell was restaged at Te Papa in 2013, reimagined as Bone Stone Shell: 25 Years On, it was done so in the context of works from both the Māori and Pacific material collections and with the inclusion of more Māori and Pacific voices, notably those of Areta Wilkinson and Matchitt herself. In this way, Ngā Hokohoko contributes to the whakapapa of conversation and reframing around Pacific cultures of adornment and identity, referring to this history and putting it in context.

The two works that lead us into the exhibition are Preston’s beautiful Paua Chain (1994) and Areta Wilkinson’s Hei Tiki (2019). Matchitt has designed this pairing as the linchpin of the exhibition and it’s easy to understand why. The two works bridge a 25-year gap in contemporary jewellery practice. They represent friendships between generations of makers that span different cultures. Both works resonate strongly with a sense of location and identity, of being made on the whenua of Aotearoa. It wasn’t until writing about this show that I realised my own connection to this hei tiki. Scrolling back through photos on my phone, I came across an image of myself trying on this very piece in a moment of deep fantasy about buying a 30th birthday present for myself.

*

A few years ago, I handled some photograms that Wilkinson and Mark Adams made in collaboration for a series of works that comprised part of her PhD and subsequent exhibition Whakapaipai: Jewellery as Pepeha at Canterbury Museum. Wilkinson connected to past makers and ancestors partially through capturing one-off photograms of taonga held in museums. A trio of Wilkinson’s works in Ngā Hokohoko titled Hine-Āhua and Huiarei, Hei Tupa and Hei Tiki (all 2013) also come from this body of research, where the photograms were used as a starting point to creating their forms. The sculptural installations and framed assemblages Whakapapa I and II are exciting additions to the practice of creating connections within a genealogy of makers. Whakapapa I is assembled from Waimakariri and Rakahuri river stones that have been used to fill a back corner of the gallery, creating a sense of the river bank. Nestled into the bed of stones are two tree stumps with a large river rock sitting on top of each. These rocks are anvil stones and bear the scuffs and marks of their use. Mounted on the wall behind them is Whakapapa II, a framed cluster of rock-beaten works in golds and silvers, showing the fruit of this traditional process.

What might our new generations of contemporary jewellers say about biculturalism, whakapapa, trade and exchange?

Ngā Hokohoko is a contemporary jewellery exhibition that explores trade between Pākehā and Māori, and references the historical and ongoing difficulties of forging bicultural relationships. It is refreshing to see an exhibition with this subject matter authored by a Māori curator and maker. This is part of a wider conversation that intersects with contemporary art, and precedents set by shows like Pākehā Now! (2007) and Kaihono Āhua: Vision Mixer. Revisioning Contemporary New Zealand Art (2013), both curated by Anna Marie-White (Te Ātiawa), that focused on biculturalism and investigated Pākehā identity in relation to Māori.

As a young Māori artist there is a lot to be gained by seeing Pākehā practice through a Māori curatorial lens. I really enjoyed this exhibition, however it left me with a major question: What do the new generations of jewellers have to contribute to this conversation? The makers involved in Ngā Hokohoko are all well established in their careers and relationships to one another in the tightly knit contemporary jewellery community. These conversations around exchange and material explorations of place, as well as the tensions between cultural, material and contextual values, are ones that have been an important part of contemporary jewellery practice over the last 40 years. I am eager and curious to see how new generations have responded and will respond to these legacies. I think it is evident that our thinking is changing and always being built upon. What might our new generations of contemporary jewellers say about biculturalism, whakapapa, trade and exchange?

The thoughts of generations and makers before are offerings gathered together and tied with a string, or perhaps woven into a bolt of white cloth. They are here on the table ready to be passed over or picked up.

Ngā Hokohoko

Curated by Gina Matchitt (Te Arawa, Whakatōhea)

2019 Blumhardt/Creative New Zealand Curatorial Intern

21 Mar – 30 Aug 2020

Feature image: Matthew McIntyre Wilson, Kete (Koekoea), 2010. Ngā Hokohoko at The Dowse, 2020. All photos by Nick Taylor.

1 In this review I have used the term Pākehā specifically to describe New Zealanders of European descent.

2 Ani Mikaere, “Some Implications of a Māori Worldview,” in Colonising Myths: Māori Realities. He Rukuruku Whakaaro (Wellington and Ōtaki, New Zealand: Huia Publishers and Te Tākupu, Te Wānanga o Raukawa, 2011), 317.

3 Alan Preston, in Bone Stone Shell: New Jewellery New Zealand (Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Craft Council of New Zealand, 1988), unpaginated.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.