Warm Dreams and Cold Stats: The Disconnect Between Adolescence and Adulthood

As you're growing up, you're told you can be anything. But sometimes you don't end up even being something, or you find you're something that the Careers Department didn't even say existed. Alec Hutchinson talks about the flow chart of his friends' successes and failures, and how it helped his students.

[caption id="attachment_7044" align="aligncenter" width="500"] "Working Late", Geoff Simmonds (2009)[/caption]

It’s easy to forget how simplistic you actually were as a teenager. Sure, in the rose-tint of retrospective analysis you were profound, nuanced and interesting, but that’s usually a fabrication, a version of you that existed at best as an inner monologue. The real you (when compared against the eloquent, interesting and worldly version of your present self) was probably inarticulate, ungainly and fairly unsophisticated. And that’s fine, except for a lot of us, it was that confused adolescent that decided on what we were going to do after high school and how we were going to reshape the universe.

I personally see this version of muddled youth every day. I’m a high school teacher. And I love it – I legitimately and wholeheartedly enjoy what I do. The only problem is the side-effect, because everything Mathew McConaughey said in Dazed and Confused is true: I get older, but they stay the same age. Where he saw this as a licentious plus allowing him to dig into gawky redheads, the reality plunges you into a startling confrontation with your own mortality and tends to foster a permanent and urgent sense that maybe you’ve made some type of poor choice. It comes out most when a kid’s had a poor grade returned. They look at you sideways, their mouths tightening in a way that is uncomfortable and aggressive: “So, who cares if I didn’t pass? You’re just a teacher.” Although I tend to reply to stuff like that with genuine empathy and aplomb, something still inadvertently rings in the back of my head.

*

As the end of each year approaches, I survey my Year 13 students and find out what they’re planning to do once state education releases them into wider society. Although not all of them have the screaming ambition to change the world, make money and be noticed, lots of them do. After my first year teaching Media Studies, a slew of kids enrolled in film school. They’d liked my class; it was a safe place for creativity and big dreams. So I was happy for them. A year after that they started coming back in to school – half to say hi, half to ask questions about what to do next. They wanted to be filmmakers, but, you know, it required money, and a crew, and distribution was an issue… I didn’t really know what to tell them. It’s hard to look into the face of someone young and earnest and give them the truth: Look, the industry you’ve decided to enter is ferociously competitive and obscenely small. Maybe you should turn it into more of a hobby? – It’s tough to say.

I bumped into one of these students on Queen Street four years down the track. Unable to find film work, he’d been employed with a construction company, hauling cinderblocks and putting up dry-wall. He hadn’t picked up a camera since leaving South Seas. “It’s all funding, man,” he said. “And it’s who you know, right.”

It was largely because of that first year that I started subtly attempting to steer kids away from investing their entire future into these lottery-style, fame-based dreams. During a class discussion in 2009 about the viability of using social media as a springboard to international celebrity, a number of aspiring filmmaker students cited Justin Bieber and Tay Zonday as evidence that Youtube could catapult them to worldwide fame and recognition. Foregoing any discussion as to whether they would actually want that kind of notoriety, statistics seemed like the best way to respond. At the time (it’s much, much higher now) approximately eighty years’ worth of watchable content was being uploaded to the site every six weeks, meaning the chance that their video specifically was going to go viral and engage a global audience was, objectively, very low. With stats like that, the quality of their work was beside the point.

The problem with these insane success stories, I said, is that they’re overrepresented in what one ends up hearing, meaning the uncritical and generally optimistic ear of Generation Y receives them as the status-quo, rather than freakish exceptions to the rule. In the end, the vast majority finish up in the great-big-middle, and that’s normal human life. In response, the students became depressed and despondent, even angry. It was like something had been taken from them. In Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, when Franny is mid-mental breakdown and complaining about her generation, she blurts out that she’s “sick of not having the courage to be an absolute nobody.” This is reflected not only in the classroom, but, it seems, well into your twenties and thirties. It takes genuine fortitude not to want to make something of yourself – a bravery it’s understandable that not many intelligent kids have.

[caption id="attachment_7046" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Excerpt from "Ghost World", Daniel Clowes (1993-97)[/caption]

This year my senior class is again filled with ambition and potential. It’s a class that comes from almost every describable social, ethnic and economic background. They make grand short films and write feature articles analysing how new media and concepts like ‘trending’ paradoxically diminish the significance of major global events. They’re smarter than I was. One kid wants to be an actor, although he has his sights set on writing and directing. Two want to be photojournalists. Another wants to work for Pixar. Another couple want to write for The Guardian and travel the globe covering stories. A handful hope to have a business up and running and be millionaires by thirty. They’re all aiming high. One even wants to be Prime Minister (although I feel his opposition to the Marriage Amendment Bill on the grounds that it’s a slippery slope to legalising paedophilia might well get in the way).

When I asked what they wanted to be doing ten years down the track, nearly all expected to be engaged in the industry that they will be studying at university. Regardless of things like socio-economic background, they all have similar and clearly demarcated definitions of success and failure, and they’re told by their parents, teachers and friends that they can be whatever they want to be – just try hard and want it enough! From my vantage point, and from a weird and slightly sinister shadow that I refuse to reveal to them, a cruel wheel of fortune lours over them all.

*

By way of gaining a clearer understanding of this disconnect between adolescent dreams and the chilly fingers of adult reality, I set about doing some quasi-research into what members of my own cohort have done in the intervening decade since high school, propelled to an extent by the possibility of compiling real human narratives that I could feed back to my class. Many of the stories teenagers are fed about the future tend to sit on the extremes of the success/failure spectrum: either it’s international superstardom and the associated benefits, or it’s the horror-show flip side of solvent abuse and prison time. The process of collecting real stories helped clarify a pattern. Of the fifty-odd people I added to my list, very few are doing now what they started out doing at university, and it appears that success at university (i.e. the completion of a degree) doesn’t have all the much influence over where you’ll end up – the only real certainty is debt.

Even as blunt bullet-points on a flow chart, all the stories are interesting. After finishing high school, Hugo spent a year on student exchange in Bolivia. The experience made him politically conscious, and so he fell into a politics-heavy B.A. After finishing first in his class he took a mining job in Western Australia to pay off his loan. At some point in this process he decided he wanted to be a doctor, and when he returned to New Zealand he enrolled in medicine in Dunedin and began accruing more debt. The last time I saw him he was close to rounding out his twenties and planning to specialise in burns.

Alternatively there’s Murray. After dropping out of school at seventeen to work at McDonald’s, his parents forced him to repeat his final year at a boarding school in Otago. Upon its completion, he started a Bachelor of Commerce, then ditched it half way through his second year, choosing instead to work full time as a bartender at the bottom of the world. When he eventually moved back up to Auckland, sans degree and saddled with debt, his parents forced him to ‘get a real job.’ He applied for an entry-level position at an export company, got it, and has been there for the last eight years, moving quite quickly up the pay scale. At thirty he’s now married and more than financially stable and his work life frequently involves international travel.

Or how about this one: four years spent completing a BA/BSc, two years working at a joinery, two years tuning pianos, a year at jazz school, and now they tutor piano and make music. Or this one: three years as an apprentice panel beater; two years selling recreational drugs; three years very happily working in an office where they can wear a tie and feel respectable. They’re all fascinating.

Only two people on the list started on a path post high school and stuck to it: Dan, who started working at an auto parts store and has eventually risen to manage a branch, and Brian, who went straight into a course in graphic design, got a job and stuck with it. Two years ago he moved to Sydney to take a similar position.

Of course, as purely bullet-pointed ‘big movements’ one loses a lot of the shading. On the chart, for example, it doesn’t say that Hugo speaks four languages and has a sense of empathy so ingrained that it’s almost violent. Nor does it say that Murray quite likes having nice things and really values owning stuff. Although revealing to an extent, the bullet-points don’t tell us why people changed or veered, only that they did, and while you tend to be able to gauge what people expect from the professional world by what they choose to study, it doesn’t get to the heart of expectations or disillusions or reasons for change.

Simon’s narrative is one of the most archetypal of my cohort. At 28, he is now going through Teacher’s College, retraining in the hope of teaching maths and finding a profession that doesn’t feel like slow motion evisceration. Having attended Auckland Boys' Grammar, his worldview prior to university was shaped to a large extent by what he was fed through the school’s culture. “I can't quite remember why I thought engineering would be my thing. I was always pretty good at maths and physics, and I guess I had visions of building great big bridges, dams and skyscrapers as monuments to my own abilities – my school was good at fostering that sense of entitlement and grand self-worth.”

He recalls the careers department at the school as being “woefully inept”; in its place, however, students were given “stern lectures by the senior teachers about how we came from a proud tradition and that we were the ones to be major players in the Society of Tomorrow.”

The shift for Simon began at university, not as a beaming epiphany, but as a slow leak: “My delusions were chipped away for various reasons – the realisation that I was not the most clever person in the world was a significant one, as was my other realisation - that I had neither the inclination nor desire to work hard enough to be among the cleverest.” Despite this crisis of confidence, he fought through to the end of the degree with what he describes as “middling to poor grades” and managed to line up a job at an engineering consulting firm. “I had this idea that that once I left university with an engineering degree I would be well placed and be able to land on my feet. As it turned out, I was right, but I hadn't prepared myself for the mind-numbing tedium that ‘landing on your feet’ entails.”

It wasn’t long before he was driving two hours out of Auckland each day to work in a company office and stare at a computer screen. “When I looked around me I saw similar blank looks on the faces of colleagues who had become too entrenched, or had families and proper responsibilities for which a professional job was a necessity rather than a way to piss around all day, like in my case.” While ‘back-in-my-day’ types often claim that we should ‘toughen up’, and that feelings like ennui or the capacity to have shattered dreams are a luxury of the middle classes, zombie co-workers with zero passion for existence are fantastic examples for why that’s terrible advice – surely they used to skip and sing and make love? Although Simon was grateful to find work at all in an industry hit by the recession, it wasn’t enough of a reason to watch his essence fizzle out: “My decision to leave after 18 months was one of the easiest decisions I've ever made.”

Simon’s story falls under a lot of what Time Magazine covered in its recent feature on the Millenials (Gen Y’ers). It posits that the effect of raising self-esteem is not necessarily a happy and well-adjusted human being, but a sense of entitlement and unreasonably high expectations. Sean Lyons, co-editor of Managing the New Workforce: International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation, was quoted in the article as saying that:

“This generation has the highest likelihood of having unmet expectations with respect to their careers and the lowest levels of satisfaction with their careers at the stage they’re at.”

In clearer language: we all think we’re awesome and so we all hate our jobs. While that kind of generalising isn’t particularly helpful for anything outside pub-conversation, there is certainly truth in the notion that this generation has been raised to believe we’re brilliant. Up-selling the potential of the kids has been in vogue with the education system and parents since the 1970s, yet it’s worth arguing that the power of media subtext has a lot more to do with it. Sure, the kid-focused entertainment of Disney has always pushed positive thinking and being the best you can be (it sells), and Nike slogans have always dominated the background of our lives. However there’s only so much that overt self-esteem boosting can do before it’s drowned out by the white noise of puberty. At that point, arguably, subtler forces take over.

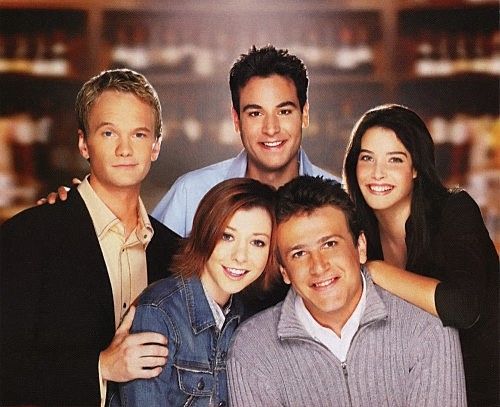

Take, for example, How I Met Your Mother. Seriously. The lives of the principal characters are meant to reflect those of the audience – the wider generation of aspirational first worlders struggling through the day-to-day grind. Just like us, they have relationship issues, drink with their friends and share inside jokes. They also whine about their professional lives and their lack of success, and that too is meant to foster a link. But it’s important to look at what they actually do. Barney, the token symbol for corporate success and casual misogyny, does something involving a suit and a huge pay check, although he never actually seems to work and has no specific skills. Robin is a TV news anchor, a job so rarefied and sought-after it might as well be the Holy Grail. Ted, at least for the first few seasons, is struggling to make it as an architect, but when that doesn’t work out he falls backward into the soft arms of academia, immediately landing a professorship at Columbia University – an Ivy League school. Marshal works a number of corporate law jobs, then, in the show’s final season and with the character in his early thirties, he’s offered a judgeship. His wife, Lily, while humbly struggling along as an elementary school teacher for most of the show’s duration, is eventually deus ex machinaed into working as an international art buyer for an eccentric millionaire. None of this represents reality.

Cultivation Theory pushes the old idea that the more we see something repeated in the world of TV, the more likely we are to believe that it occurs in reality. For example, people who watch a lot of crime shows tend to believe violent crime occurs a lot more often than it actually does. It’s natural, then, to extend the theory into something like the potential for success in over-supplied and competitive industries. The entire fictional cast of How I Met Your Mother managed to do it, so I’ll be able to do it too. If the message is repeated long enough and wide enough, then it enters the zeitgeist. It’s like hearing a song quietly in the background of lots of different shops: eventually you start humming it, but you don’t know where the tune came from.

To extend that simile, it’s fair to say that they potential for success song is being played in just about every shop: Rory Gilmore got into Yale; Ugly Betty landed a job at a high fashion magazine in New York; Method Man and Redman smoked themselves into Harvard; Carrie Bradshaw managed to feed herself as a lifestyle columnist, etc. And that’s without delving into more current examples, or Reality TV. While this might sound hyperbolic as an adult, you can’t underestimate the degree to which values and beliefs filter through media and into the fresh-faced and nascent. TV shows are more understanding than religion and more entertaining than your parents – it’s always been that way.

Dave’s story (not his real name) is a good way to illustrate some of the real world effects. I met him when I was nineteen. At the time he was twenty-nine. His career path was a lesson to me, and now it’s a lesson to my students. He enrolled in Law because it sounded good. Despite gaining a C degree, he inexplicably landed a law job at a mid-sized firm. After six months working there, his employers (who presumably should’ve read his transcript) told him he was the worst lawyer they’d ever hired. He quit before they could let him go. At twenty-six he decided to retrain. If he couldn’t be a lawyer, he’d be a doctor. And so he did a preliminary year, then two years of a health science degree, but when it came time to make the push for medicine itself he came to the personal conclusion that he wasn’t smart enough, and so he dropped out. At twenty-nine – when I met him – he’d decided to be an actor. I watched him try out as an extra for a number of commercials – that out of focus guy in the background you see for two fifths of a second. I watched him fly to Australia to audition for the stage production of The Lion King. When he couldn’t land anything, he decided it was because he’d never been to acting school, so he flew to England to try out for some. He was eventually accepted into the Drama Centre London, but at around $60,000 a year, he wasn’t all that sure it was worth it, so he flew home.

I wasn’t particularly sure he ever had a fondness for any of the fields he tried. He just liked the ring they had. Doctor, Lawyer, Actor. They dripped with significance. In the end it was this desire for significance that crippled him.

*

It could, however, be a simple problem of labelling. It’s rare to see niche jobs peddled through mainstream media characters, and it’s even rarer for parents and teachers to push them (maybe because they simply don’t know they exist). The standard call is to study hard so you can be a doctor, engineer, lawyer. You don’t often hear, ‘study hard so you can be a systems analyst or a digital consultant.’ It’s here that Ryan’s story becomes interesting.

By all accounts Ryan is among the most successful members of my cohort (if success can be defined here as being financially stable and in high demand). There’s a good chance he’ll be the first person I know to make the transition to pool ownership. Yet nothing about his route is traditional, and most of his twenties were spent bouncing between cities and interests.

During his 7th form year his family moved to Auckland. He spent all of two days attending the high school that I now teach at before he made the decision to just stop going. A month later, his parents were informed about his mass truancy and forced him to get a job, and soon he found himself working at the ihug call centre. He recalls feeling that if he’d finished high school, he might have gone on to study “computer programming or something along those lines” – a nerdy hobby he enjoyed outside of its obvious profitable potential.

At twenty he had what he describes as “a flip-out”, gave away everything he owned and hitched down to Christchurch to work for a charity call centre and hang out with “hippies and homeless people in Cathedral Square.” By twenty one he was back in Auckland, working part time as a subtitler at TVNZ and studying – at university now – to be a Christian minister. A year and a half after that, he “stopped being Christian” and moved to Wellington, this time to pursue a degree in comparative religion and philosophy, and then a year after that (there’s a pattern forming here) he was back in Auckland to finish his philosophy degree. While there, he made new networks of friends and ended up editing Craccum, the official student magazine, in 2006. The position meant he had to put his postgrad studies on hold: “It turned out that disqualified me for my honours degree, but I stuck around studying for a postgrad diploma while tutoring first-years and still working at TVNZ. I never finished any of those courses, and I'm still paying off the student loan.”

That said, his ability to network and engage with people saw him end up working for Smirnoff in 2008, helping to run an experiential marketing campaign. When that ended, he decided to try his luck and on a whim called Shift, the company that had created and managed the website for the campaign. “I asked them, ‘Do you guys have any clients who might need a Facebook page run for them? Is that a job that I could get maybe three hours' pay a week for?’ They called me into the office to interview as a ‘generalist’ and suddenly I was working there full-time, doing whatever needed to be done.” Following a year at Shift, Ryan “stepped sideways” into a strategic role at TBWA\TEQUILA.A year after that he moved to the Manukau Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Business (devising their marketing and communications), and a year after that (check that pattern again) he moved to Sydney to work for Zuni as a “digital strategist.”

His life has all the hallmarks of Gen Y. He hasn’t stuck anywhere long, and he now works in a job that didn’t exist when he was in high school. He’s made more loose choices than most – often, it appears, annually – and he makes them actively and boldly. If something doesn’t work out (he describes his time in Wellington as “kind of a nightmare”) he learns from it and moves on. Sure, he’s not the sitcom writer he’d hoped to be, but that doesn’t matter anymore. People change. “I'm the guy my past self would have hated. I'm the guy my past self would have quoted Bill Hicks at and left. But fortunately, I'm also the guy who's enjoying doing what he's good at and is certain enough of the usefulness of these skills in the future that I'm not too worried about what Bill Hicks would say to me. I'm already helping people with them, and will help more as time goes on.”

The thing is, none of what Ryan has ended up doing can be correlated to what he studied at high school. There was no career guidance, no set path, just lots of personal testing and moving. Along the way he picked up an armoury of arcane skills that have seen him through to stability and a level of comfort. “It took me almost thirty years to realise that almost no one has any idea what they're doing… Until relatively recently, I made no conscious decisions about my career. I just took what I could get, fell from one thing to another. In the past few years, I have actually said to myself, ‘Okay, this is what you're good at and what you're doing. So – what next? Whose reading recommendations do I seek out? Which blogs do I read regularly? What do I need to know to be better at this?’”

Surely there’s got to be a lesson here. Most of us make lots of rigid decisions too fast. Ryan made none, riding instead on personality, moxie and luck, and that’s not something that can be peddled in schools as the smart choice.

*

People often retrospectively – and erroneously – blame their careers department for steering them in the wrong direction, as if in hindsight it was the single factor in their picking an unsuitable industry. My own recollection of the careers department during high school is limited. I remember that in sixth form an archaic computer programme suggested I should be a chemical engineer. When I bottomed out in the necessary subjects, a school visit from the University of Auckland led me to think maybe Law was a good idea. In honesty, this was all of five minutes’ thought. At the time, I was much more concerned with beer and skateboarding and having people like me. Career paths were something for the immutable distance.

The students I teach today take a similar view of the careers department, suggesting the advice you get there is about as relevant as a floppy disk. Jay, a Year 13 overachiever, said that “the careers department try to point you in the direction of an imaginary place, but that’s it, and the advice they give you is obvious, like, if you want to be a lawyer, take law.” Another student – a high-flying member of the academic council and already well on his way to tertiary study – was more philosophical: “They tell you to keep your options open… The problem is, though, I don’t see what else they can do.”

And he’s right, because the kids I was chatting with are doing reasonably well academically, the type that write two pages instead of the minimum one, and a trip to the careers department itself confirmed its irrelevance for them. Located strategically next to the school nurse, the office is hemmed in by brochures about gonorrhoea and working in the tourism industry. While the department aims to cater for every student, and makes a point of arranging one-on-one conferences with the entire student body, it’s really a place for those who are struggling with the fundamentals of school and lack a parental push in a specific direction. For the three quarters of the school that already know or have been told by their parents what they are doing, it’s a space that doesn’t invade their consciousness much.

The Year 13s’ recent trip to the Careers Expo, albeit well intentioned, solidified this. Held at ASB Show Grounds, for most it was an excuse to be out of class and get a free tote bag. To quote one of my students: “Unless you wanted to join the army or make a career in hospitality, it didn’t have much to offer.” I was tempted to tell him that NZ currently has over 15,000 full time waitresses and waiters, and for a guy who claims to be “on the left” he seemed pretty aloof about these prospects, but I let it slide.

That said, some things in the careers department have definitely modernised. Instead of being given a seat at a Commodore 64 and directed to follow the steps to find your destiny, students are now guided to the government careers website – a practice that is apparently standard around most high schools. Although this is no doubt a good tool for the young and unsure, if you’re old and stable and in no mood to be demoralized, it’s a terrible site to check out. It will tell you how unsuited you are to your current job, that there’s no work in the field you want work in, and that everything interesting requires a lot more retraining and experience than your life has time for.

Beyond the careers department, schools also employ an academic advisor – someone whose role is to ensure that students are taking what they need to take, as well as using data to monitor progress and oversee academic coaching. In many ways, they pick up what careers can’t. Neil Waddington, one such academic advisor, gives one-on-one advice when students are referred to him: “I stress to them the importance of real understanding of what a career involves, using anecdotes of people I know…” Like being a doctor will involve being in contact with lots of demoralising sickness, like being a lawyer will involve photocopying and memorising and standing around for long periods of time in rooms with shitty depressing lighting, and being a lab technician will involve you doing the same thing over and over to check if anything has changed.

He continues: “I consistently counsel the importance of students keeping doors open and having a Plan B, ideally also a Plan C and maybe beyond, particularly if they have aspirations in the creative or niche industries where there is a lot of competition for the few jobs going.” Some statistics from the government careers website can help to reinforce this. According to its sources, only 284 people were working full time as actors in NZ during 2012. There were 136 directors and only 82 models. On the flip side, there were 30,094 cleaners, 84,208 sales assistants and 59,545 sales representatives. Waddington is also savvy enough to know that we live in a radically different world now: “We are told by ‘those who know’ that we don’t know what students will end up doing, that jobs they will do have yet to be invented…” A description of Ryan’s job as a digital strategist, for example, doesn’t even show up on the Careers.govt.nz website.

But Waddington also identifies a fundamental problem – one that sets itself in mortal combat with the idea that we should all take our time, explore our options and/or chase our dreams. Traditional wisdom suggests that we’ll all change careers at some point – like Ryan’s bouncing from place to place, like Simon’s shift from engineering to teaching. The problem is that universities are increasingly tying themselves to the professional world, and while that’s great for them, it’s crap for anyone who wants to move industries mid-stream.

Waddington, again: “The increasing requirement of most professions to have four years plus tertiary level education for an entry qualification reduces peoples’ ability to completely reinvent themselves, particularly if they are the breadwinner for a family.” By making the leap, you’re often putting yourself at huge disadvantage: three years, another student loan, and even once you’ve got the necessary paperwork, you return to GO at an entry level position. The older you get, the more perilous a decision like that becomes. Waddington coolly reaffirms this with his own experience: “People I know who are now middle-aged and financially secure tend to move along a pathway rather than stopping and going back to the start before trying a completely new track.”

So what’s the call? To hell with acting – if you really like it, then you won’t mind doing it for free after work at a community theatre. For the day-to-day stuff, pick something stable that you don’t hate and stick with it. And when the seventeen year old version of yourself screams down through the timeline and calls you a sell-out and a fraud and a failure, smile politely and remind them that their mother still drives them places, that real life is slow and good things take forever – just look at Joseph Heller and Catch 22.

And that returns us to the original thrust. Teenagers usually have big dreams, and for this we can’t fault them. They are the products of vicarious parental ambition, teachers who use celebrity levels of fame and money as a motivating carrot when the stick doesn’t work, and – mostly – a media landscape where even ice-cream adverts tell us our fantasies should be for red-carpet stardom and respect. It would also to be foolish not to acknowledge an innate desire in us all to lead a life of meaning; being noticed can help to validate your existence.

Back in my Year 13 Media classroom, I’d printed out the bullet-pointed lists of my fifty contemporaries and their various professional journeys and handed them out to the students. Here were real human narratives, filled with indecision and false starts and big moves, some high flyers, some still trying to sort it all out. The students’ reactions were varied, and a few were frighteningly negative. The student who wants to act and direct simply suggested that those who hadn’t ended up doing what they started out doing “probably weren’t working hard enough.” Another found it depressing, because “I know what I want to do and by the looks of things, that’s not going to work out.” Most, however, found it liberating. Having been drilled into believing that if they don’t work hard and go to university they are destined for mediocrity, they suddenly saw names like Sean, who didn’t manage to get Bursary but is now a Crown Lawyer, or my own girlfriend, who left school at sixteen but now has a degree and works at Auckland Art Gallery. For those kids, it helped redefine what success might mean, and it let them know that if they didn’t want to do the same thing for the rest of their lives, then why would they?

Because there is the crux of the issue: At seventeen, you’re nowhere near equipped to be in charge of your future. As Ryan put it: “I was a fucking idiot. Hell, I'm still a fucking idiot. But seriously: seventeen years old. No position to be mapping out the life of an adult.” So maybe you should put it off… wait it out for a little… do something interesting. But if suddenly you get to thirty and you still don’t know what you’re doing and you’re stuck an industry you hate – well, at that point it’s going to start to cost you. Unless you have an odd mix of skills, connections and personality to get involved in a job that doesn’t exist yet, then you’re riding the snake back down to Level 1. That’s life. It’s cold and it doesn’t care about you.

*

[caption id="attachment_7050" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Kids at the Carousel in Forest Park, NYC, Sept 1940.[/caption]

Maybe one of the questions this all raised is the role of the teacher. What is my job? What should I be doing? The rather forward-thinking modern curriculum suggests that I should be teaching students how to learn and how to think critically about the world. In English, the aim is to get them making meaning out of the world and creating meaning for other people: subject matter is secondary to skills. So shouldn’t I be helping them make informed decisions about their future – giving them the tools necessary to guide themselves away from the perils of false hope, a sense of entitlement and nuclear-grade expectations, trying in some way to counter the gleaming quixotic onslaught with circumspect rationality?

Maybe the answer lies with Salinger again. At the end of Catcher in the Rye, Holden is sitting on a bench in the rain and watching his kid sister ride the carousel. She’s reaching out for the gold rings that hang off the eaves in the hope of grabbing one and winning it as a prize. The problem is, some kids fall and hurt themselves in the process, and so this makes Holden nervous. He doesn’t want to see his sister – a picture of hope and innocence – bail off her horse and grind her face on the cement. But he stops himself from intervening. The same Holden who has spent the entire book trying to save kids from the evils of the world suddenly has a clumsy epiphany: ‘If they fall off they fall off, but it’s bad if you say anything to them.’ So when it comes to warning kids about swirly trials they’re inevitably racing toward, maybe we should just step back and watch and enjoy it all – the latent violence, and the ballet of their attempt.