A Walk Through My Eyelands

What do you do when art spaces aren’t ready for you? You make your own space. Rosanna Raymond traces the do-it-yourself anarchists, night clubs, warehouse parties and hip hop gigs that gave her a place.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Reflecting on my journey into the arts, I need to reach deep into my manava to recollect the flotsam and jetsam of an arts practice that spans three decades now. I’m talking last century, pre-social media, when analogue ruled the world. Art came to me in a roundabout and sometimes painful way, yet now it is permeated into the core of my being and my doing. The journey is interwoven with my quest to find sacrosanctity as a third-generation New Zealand-born child from the Moana, of French, Irish, Sāmoan and Tuvaluan descent.

The light of my life was my Sāmoan grandmother, who smothered me in unconditional love. Malia arrived in Aotearoa in the late 1920s at the age of 18, far ahead of the mass migration in the 60s and 70s. My father was born in Auckland in the 1940s and was punished for speaking Sāmoan at school, and had very few support networks around him or a large Pacific community like that which exists today. Racism and sexism was apparent even to my young eyes and ears. My Pālagi mother endured public insults directed towards her because of my brother and I. So at a young age I became aware of my otherness, not fully European but not Sāmoan either. Afakasi was the term I was brought up with. I didn’t understand this term at the time, but it turns out this was not to be the last time that my body was constructed or couched in negativity by other people. Young and old, brown and white. In 1976 my brother and I were taken to the far north of England, where we spent the next two years before relocating to Christchurch in the 80s, where I spent my adolescence.

If I gaze into my childhood and look for art, I see it in the hands of my matriarchs, on both sides

If I gaze into my childhood and look for art, I see it in the hands of my matriarchs, on both sides. These women had busy hands, makers’ hands – crocheting, knitting, sewing, embroidering. I remember my mother painting when I was maybe five or so. On the bookshelf were numerous books on the master painters of Europe. Mum would send me to art and craft sessions in the school holidays, taking my brother and I to many galleries and museums. I grew up thinking art was to be found in galleries, hung on walls, carved in marble. Whereas Pacific art, on the other hand, was primitive or tribal and to be kept in museums.

Thanks to my education, this was further entrenched in my young head. I took art as an option in the fifth and sixth form, where they continued to impress the Western notion of art on me, using the same European masters I had seen in my mum’s books. I have a vague memory of encountering Māori art – we had a trip to the museum specially for that. The curriculum focused on the European art forms of painting, print making and drawing – that was art. There was no encouragement or understanding of my cultural heritage or interests and it was made clear that art was really a hobby, not a serious subject. By the time I left school any artistic ambition I might have had was well and truly squashed.

So where did I find art? Back in the early 80s, I found it with the do-it-yourself anarchists who lived down the road from me. I found myself learning to screen-print anti-government propaganda posters with late-night runs taking our messages to the streets. I became an expert in sewing and customising my clothes, hand dying and printing t-shirts. Adorning my body with safety pins, chains, complete with Souxsie Sioux eyes, black lips and soap in my hair to tame the curls.

Pacific Sisters Ani O’Neill, Suzanne Tamaki, Rosanna Raymond, Feeonaa Clifton (Wall) Fundraising Frockery, Karangahape Street Markets, Auckland, Aotearoa NZ, 1995. Courtesy of the artist

My body has always been a contested space. Not so much by myself but by others, which had a profound effect on how I viewed myself. All the relocating, which has continued throughout my adult life, deeply impacted my identity. The term afakasi was replaced by the term half-caste, and I had morphed into a rebellious and defiant teenager pushing against a society I was not comfortable in.

My body has always been a contested space. Not so much by myself but by others

A new body was about to (con)form. During the mid 80s my mother sent the defiant body to a modelling course in the hopes that I would maybe stand up with my shoulders back and get my soaped-up hair out of my face. That body became a commodity to be displayed, used as a coat hanger to sell clothing, cars, and the odd toaster – it also moved again as I found myself in Italy, Germany and Australia. Eventually coming back to my homeland in 1989.

Back home, walking down the streets of the Auckland CBD, I found myself surrounded by ‘nesian bodies. These bodies were often fraught, they did not sell you holidays in the sun, they did not appear in the mainstream media. These were invisible bodies, faceless, nameless often only reflected in data counting the unemployed, the incarcerated and the hospitalised. These bodies bore little resemblance to the Dusky Maidens and the Noble Savages that most Europeans associated them with. Now wearing jeans, sweat shirts, workers’ overalls, gumboots, steel caps, high heels, they assimilated into life in Aotearoa. We had no reflection of ourselves as an urban community living in New Zealand besides what had been constructed for us by organised religion, mainstream media and the colonial past.

Some, like me, had travelled and returned home inspired from the experiences of living in the world’s major cities. We had a different experience from our parents and grandparents. We often sat outside our own Pacific Island community, not feeling comfortable in the churches; our lack of language and anger at the acculturation of past generationsmade an uneasy pact with our elders. We met in the night clubs, at warehouse parties, hip hop gigs and festivals. Pacific artists, musicians, DJs, jewellers, fashion designers, writers, dancers, bouncers, activists mingled with Māori and Pākehā, all contributing to the burgeoning street culture that was developing its own native flavour.

By now I was married (in an art gallery) to a well-known photographer, Kerry Brown, and had my first-born son, Salvador. I was still working in the mainstream fashion industry, mainly as a fashion stylist – co-ordinating shoots and casting models – with Kerry. This is where the true scope of racism in New Zealand was apparent, and played out in magazines and on our TV screens. The ‘nesian body was not welcome and nor was anything that adorned it, unless it was in fashion, doomed to disappear when the next trend arrived.

The ‘nesian body was not welcome and nor was anything that adorned it

Mainstream media did not reflect the world I inhabited. I’m trying to find the words to describe the energy on the streets and in the clubs. It was intense, urgent, experimental, sometimes detrimental. It was a refusal to accept the white mainstream dream as the benchmark for success, and a realisation we couldn’t afford it anyway. It was driven by a need to be recognised outside the bicultural agreement of the original Treaty partners that rendered Pacific peoples in Aotearoa invisible. We had been relegated to the ‘other’, seen the same as Pākehā, our shared histories and bonds as people of the Moana trampled on. It was driven by a need to be seen and heard. It was tino rangatiratanga with hibiscus overtones, as we had learnt much from our Māori cousins.

Street culture and fashion was my entry into a creative practice, as I started showcasing the work of the artists and designers that I met during the nights. The clubs were my galleries, the streets my theatre, the cafés my university. A then unknown photographer, Greg Semu, and I formed a creative team, working with magazines such as Planet, Stamp and the university-run Monitor. We produced imagery that spoke to our urban New Zealand-born community – it just didn’t exist then. These magazines let us dictate what and how we saw our place in Aotearoa – urban, multi-cultural, funky, political, brown and proud. They did not tell us we were inauthentic or that we were only a trend, they let us celebrate our part in the niu cultural landscape of Auckland on our own terms.

Pacific Sisters outside the opening ceremony of Tala Measina - Unveiling of Treasures at the Seventh Pacific Festival of the Arts, Apia, Samoa, 1996. Courtesy of the artist

There was a lot of pressure on us all financially – we worked for very little money. The way funding bodies were structured didn’t help either, as there was no allowance for multi-cultural groups. With little institutional support, we developed our own frameworks and networks, selling second-hand suga frocks and our handmade adornments at markets to fundraise and sustain our projects. This was hard work, partly because we had very little in terms of precedent and very few people in our community who could or would mentor us. That was until we shared some space with the Pacifica Mamas out at Corban Estate in the late 90s. We connected with this group of elders, who appreciated the craft skills and deep-set kaupapa we embedded in all of our mahi. We would exhibit together and included their mahi in our shows. The support of these women was important to us, as we had been excluded on many levels.

The Pacific Sisters was and is a multi-cultural group, wahine-centric and unapologetically urban – this was met with much suspicion by our own Māori and Pacific communities. We were thrown out of the 1996 Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture (FESTPAC) in Sāmoa at the request of the Māori contingent, even though we had been officially invited by the festival director. The newly formed Pacific arts body Tautai didn’t acknowledge us either. A major project in New Caledonia was cancelled last minute, as it was feared we were too political. Nephi and I were airbrushed out of a photo for an article on the Sydney Biennale in The Sydney Morning Herald. I could go on.

It was during this time the term Urban Pasifika was coined: we had arrived

Our initial presence in the art gallery space was nanoscopic – we had become arty by association due to our relationship with Ani O'Neill and Lisa Reihana, who were gaining local and international art-world recognition. Our domain was still underground. The Pacific Sisters were live and direct, decorated in leathers and feathers, shells and tusks, tapa cloth and tatau. We then started to colonise empty shops, exhibiting the costuming we were making. When we did finally enter the gallery space, it was one of our own who invited us in. Toni Symons, a long-standing member of the Pacific Sisters, curated an exhibition called Lapa at Lopdell House (now Te Uru). This was our first foray as a group into an actual art gallery. From there Ron Brownson invited me to exhibit in Open Skies Divided Horizons at the Auckland City Art Gallery, where I installed La'a La'a Luga le Fanua o le Mata (A Look through My Eyelands) alongside artists who I had long admired. The National Gallery of Victoria bought a costume from me that I had made for a Pacific Sisters exhibition that Giles Peterson curated in 1997. Only at this point did I allow myself to think I could be an artist, though I still wasn't sure.

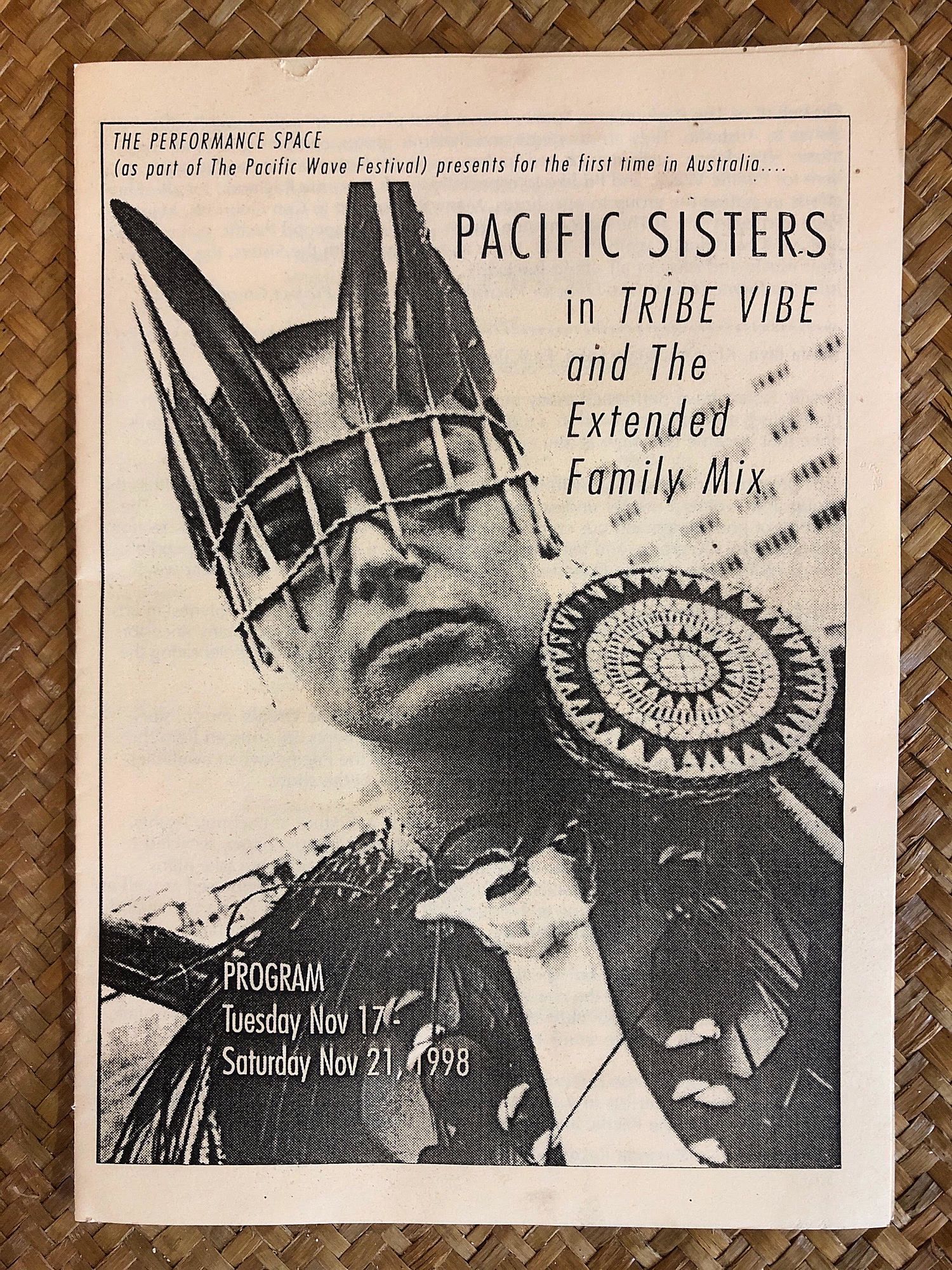

Pacific Sisters Cyber Sister Ema Lyon, Tribe Vibe and the Extended Family Mix, Pacific Wave Festival, Performance Space, Sydney, Australia, 1998. Courtesy of Rosanna Raymond

The relationships I formed back in the 90s changed my pathway, enabling me to develop into the artist I am today. It was only by working in a collective and having an extended family that supported me that I managed to develop a creative career. As a creative community, we had to generate our own platforms to reveal that New Zealand was indeed an island in the Pacific. It was during this time the term Urban Pasifika was coined: we had arrived.

And then I left to live in the UK and that, my friends, is another story.

CNZ Logo

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group. Photo by Raymond Sagapolutele.