Waitangi Mon Amour

Artists and writers share their illuminating, provocative thoughts on Waitangi Day

What does Waitangi Day mean to you? We asked some of Aotearoa New Zealand’s artists and writers – cultural leaders whose voices we often don’t get to hear on this anniversary. Here are their illuminating, thoughtful, provocative answers.

A good day for quiet contemplation

Aroha Harris (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi)

Historian, Waitangi Tribunal member

I have probably spent more Waitangi Days working than enjoying any one of the numerous events available throughout the country, not because I've had to work, but because I think it’s a good day for quiet contemplation – to read, think, write Maori history.

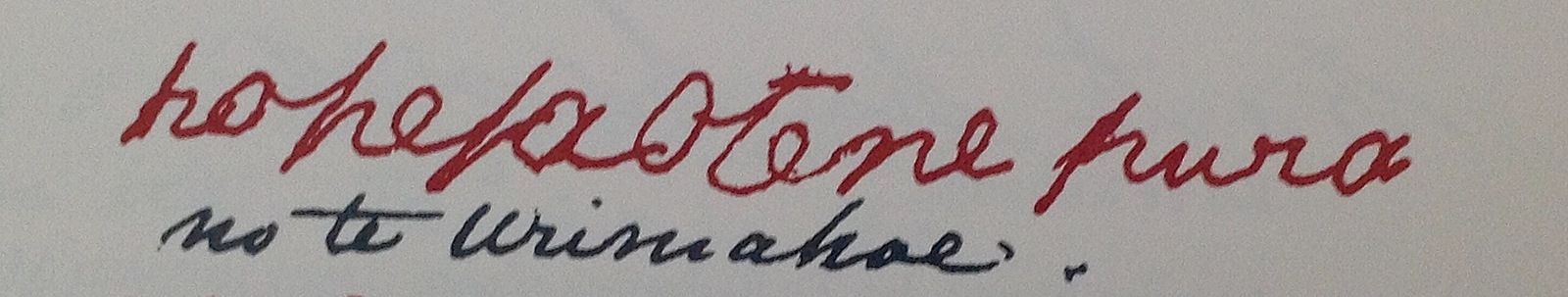

History: My tupuna Hohepa Otene Pura signed Te Tiriti at Waitangi on 6 February 1840. That's his signature above. He is my great-great-great-grandfather – three times over because three of my dad's four grandparents descend from him. I like to think about him signing his name, engaging with the critical issues of the day.

As a day of commemoration, Waitangi Day offers many options. Some years I have enjoyed free music in public parks in both Auckland and Wellington. In other years, I have had a completely different experience at the Governor-General's Waitangi Day receptions. Waitangi Day at Waitangi itself has been a long-time favourite – a sunny family day, colourful and spontaneous, stalls, music, kapa haka, waka, political debates. So much fun.

Contemplation: It saddens me that so many people seem to take the well-worn mainstream media depictions of protest and discontent (which in my mind shadow the politicians, not the occasion per se) as representative. They argue against Waitangi Day, while its festive and spirited personality is edited out of our public memory.

She never longed for the life she had left behind

Brett Graham

Sculptor

This Waitangi Day I won't be celebrating. I'll be at an unveiling for the headstone of a Pākehā lady who came from England in the 60s. Back then, she went to a party and fell for the Māori guy with the guitar, they got hitched, and had five children. Aunty Viv died on Waitangi Day last year and every day of her tangi there were literally hundreds who came to say goodbye. Māori and Pākehā. Many of those who came didn't even realize she was English. She fitted into Pā life so completely, attending every hui, relishing every custom and protocol, embracing the culture, and as far as I know she never longed for the life she had left behind.

She made no ideological speeches. She just lived her life, loved her husband and children and embraced their culture. And we all loved her for it.

Waitangi Day is a glitch in the vanilla matrix

Ema Tavola

Artist and curator

This past year, I’ve become so disillusioned with New Zealand politics, media and the mainstream milieu that I have disconnected almost entirely. I don’t want my ‘news’ through the lens of dominant culture, and I’m tired; racism – whether casual, structural, innocent or face-to-face, Mad Butcher style – has made me weary.

My altered reality has become a healthier, empowering space. I am embedded in a carefully curated, conscious community. Cultural safety, knowing and understanding the historical trajectory that planted us here, and the advocacy, energy and aroha that pushes hard against the infrastructure of our world, gives me life.

There are so few opportunities for those with the privilege of dominance to feel weary in their skin, confronted by history, or affected by injustice. Waitangi Day isn’t the answer or the Secret, but it is an annual shot of psychological equity to soothe the disease of inequality.

I take comfort in the discomfort Waitangi Day causes for the historically challenged. For the voices that I privilege in my new media landscape, Waitangi Day is a glitch in the vanilla matrix, an unavoidable reminder that colonisation was/is enduring and powerful, but not entirely successful. It’s a day to honour decolonisation and its embodiment and dream in real time about a radically different future.

Bloated fairy bread floating in glasses

Alice Canton

Theatre practitioner

Every year, we have Waitangi Day. Every Waitangi Day, we get a year older. Last year, I got older. I had a party. Perhaps Waitangi Day is a kind of national birthday party. A party with music and dancing and flared pants. And beautiful collisions between combinations of friends, strangers, lovers and family. Vodka and fireworks. Something with a bat and ball and running and point scoring. Laughing, shrieking, barking and grunting. Fighting (and fucking). Speeches. Hand shaking. Hands shaking. Back pats, back rubs. Sunburn. Soggy sausage rolls and bloated fairy bread floating in glasses and cans and bottles and ciggie butts in punctured paddling pools. Splintered deck chairs, blown out speakers, bikes in trees, burning rubber. Broken windows, soiled carpet, messy wet bedding. Knocked-out letterboxes. Knocked-in teeth. Lights, sirens, paddy wagons. Barking dogs. Crying babies. Abandon. Abandoned.

Every year I get older, I have a party. A big, sad, wild party to celebrate how far I've come. Look how far I've come.

Look at how far we've come.

A celebration of the sheer perseverance that Māori have displayed

Julie Zhu, Asians Supporting Tino Rangatiratanga

The struggles of Asian migrants (and other migrants of colour) especially around discrimination, marginalisation and scapegoating in Aotearoa needs to be understood in a context of colonialism first and foremost. Waitangi to us is a necessary time to recognise the absolute sovereignty of tāngata whenua in Aotearoa and reflect on the history of colonisation that Māori have endured and continue to endure today. It’s an important reminder of all that we still need to do in order for mana motuhake (self-determination) to work in practice for mana Māori, as well as a celebration of the sheer perseverance that Māori have displayed over the years in terms of unrelenting resistance against colonial actions that have undermined their sovereign rights.

Waitangi is a time to show respect and honour those ancestors and rangatira who have come before and acknowledge the responsibility within all of us in Aotearoa to continue to uphold the fight. Ka whawhai tonu mātou. Ake ake ake.

I frequently had to stop, walk away, take a break, calm down

Airini Beautrais

In August 2014 Ruruku Whakatupua, the Whanganui River Deed of Settlement, was signed. Whanganui iwi had taken a claim to the Native Land Court in 1937. The story of the intervening years is filled with setbacks and frustrations, as well as further injustices such as the taking of the Whanganui headwaters for power generation, authorised in the 1950s without consultation with iwi.

The Waitangi Tribunal report for the Whanganui River claim, as with other Tribunal reports, makes incredibly sobering reading. Approaching it, I frequently had to stop, walk away, take a break, calm down. But I think everyone should read these reports, especially those relating to their local area. The reports contain first-hand accounts of what happened. Many of the people who gave evidence to the Tribunal have since passed on. We need to know what they had to say and remember what they stood for.

For me, as a Pākehā, Waitangi Day is about listening. Pākehā and our institutions have done a lot of talking – and taking – since 1840. Political leaders should be there listening, not elsewhere complaining about where or how much they are allowed to talk.

I'll seem like a time-traveller from the 90s

Tze Ming Mok

Commentator

I have noticed in the ten years since I left New Zealand that mainstream discourse on Waitangi Day and things Māori, led to some extent by the education system and the media, has made some progress. Expectations are higher. History books are better. Te reo is more prevalent, and better pronounced. Māori journalism and journalists are ever more prominent and influential. Even the Herald online will randomly publish Māori terms in headlines from the Rotorua Daily Post that I have to Google.

Basically, I have a lot of brushing up on Maori and the New Zealand Wars to do before I move back as planned, otherwise I'll seem like a time-traveller from the 90s who was taught more about Garibaldi and Metternich at school than Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Potatau Te Wherowhero.

Title image: Marcus King's 1939 imagining of the scene at Waitangi on 6 Feb 1840. Hobson is shown in full uniform but actually wore civilian clothing. Source: Archives New Zealand

Ella Grace McPherson-Newton's 2017 take on Waitangi Pride and Fear is here.