Urban Legend: An interview with Dove-Myer Robinson's Biographer

He's best known to the 21st century as central Auckland's best monument - but a new biography of six-time Auckland mayor Sir Dove-Myer Robinson showcases a man with ideas forty years ahead of their time, and reminds us how history can repeat, especially in local government.

My favourite monument in Auckland is a little, bespectacled old man some 10 inches shorter than me. His jacket is slung over his arm and he is waving his fist at the Auckland City Council’s offices in Mayoral Drive from the far end of Aotea Square. Even in stoic and modest New Zealand, our civic leaders tend to end up triumphant and bronzed on plinths, larger than life and possibly on some sort of horse. Dove-Myer Robinson, Auckland Mayor from 1959 to 1965 then again from 1968 to 1980, has not ended up like this. It’s a rare example of self-aware urban tribute.

For the August issue of 1972Magazine, I’m writing a feature on Robinson and historian and lawyer John Edgar’s new biography of the man, Urban Legend: Sir Dove-Myer Robinson (out now through Haclette Publishers). It’s a cracking good read that balances Robinson’s remarkably prescient ideas on the environment, local government and mass transit with his often scandalizing personal life, while conjuring up the most remarkable ersatz Auckland of patchwork fiefdoms and bruiser evening papers that’s otherwise been lost to time. Below follows the transcript on my interview with Edgar about the book:

I saw it was as early as 1982 that you first met up with Dove-Myer Robinson. What precipitated that?

I was very interested in history – I’d finished an honours degree in it and always visualized myself as a history lecturer, although things didn’t work out that way! There were very few jobs and positions going, and at the time I would have been going into that line of work New Zealand was in the middle of one of its regular recessions. So I was looking around to do a doctorate in history, I thought it was going to take a reasonable amount of time. I did end up getting the thesis in on time!... although the book took a lot longer. And I wanted to do it in political history because politics interested me, but I also wanted someone who was interesting – and a lot of political figures in New Zealand have been, unfortunately, rather dry creatures. Plenty of them, I think, still are.

By this time he had left office as Auckland Mayor. He had been defeated in 1980 and then although he ran in ’83 and again for Council in ’86, that 1980 campaign effectively bought his political career to an end. So I think he was eager for the attention and flattered that someone wanted to write a PhD thesis on him. So I wrote to him, he wrote back very quickly and enthusiastically and we met up from there. It became clear from our first meeting that he would be very candid, and so I knew then I had my subject.

That picture you paint of the last decade or so of Robinson’s life – it seems like he was someone who was very used to being in the spotlight, who reveled and really thrived under it – and when that light was taken away, he’d write to papers, he’d actively seek media attention. But he seemed to find it all quite difficult.

I think he found it very difficult. Because it was such a long tenure. He had six terms in office as mayor, punctuated by one three year gap in the middle when he was still on a local government board. And then before that, he’d had all the attention – though a lot of it was negative – with the battle to stop sewage being dropped into the Waitemata Harbour. So it was a huge period of his life where he was a subject of interest, and then it was gone. I call it ‘limelight deprivation syndrome’, and I think a lot of politicians suffer from it.

And it’s interesting, because he wasn’t like those elected officials who find themselves turfed out of office in, say, their fifties, with years before retirement ahead of them and nothing planned for it. He was an elderly man.

He was 79 when he was forced from office, when he lost the election. And he was told by so many people not to contest that election, including his mayoress. She knew his time was up, but he couldn’t see it. I think that’s another thing with a lot of politicians – they become very convinced of their own importance, to the point that they sort of see themselves as irreplaceable.

In saying that, at no point do you get a sense of him being a traditional mode of politician. He didn’t get into it until he was pushing 50, he doesn’t function as a team player in that he never really picked a side in Auckland local government and stuck with it. He never had a conventional political identity or brand apart from those things that made up his particular passions and interests.

I think that’s true, and I think that was there from the start. He first reached public office in 1953 as part of this group that had coalesced to stop that sewage disaster – and their name says it all, ‘United Independents’. They could have what philosophy they liked basically, as long as they agreed on not pumping more garbage into the Gulf. And I think it goes back to his childhood. I think he was a real loner of a child, and I think I understand why. Particularly the situation he had to deal with in England.

So maybe that impulse to withdraw into yourself, and to be self-sufficient with that, is one he never lost.

The details of his childhood at the beginning of ‘Urban Legend’ are quite vivid and sometimes exceptionally harsh. Were these recollections that you were told straight from Robinson himself?

Yes. After that initial meeting, which would have been early in ’82, that was one of the things he mentioned even then and actually formed one of our lengthier interviews. So all of those things that had happened, by then 70 years ago, were actually incredibly clear and picture-perfect to him. Including names and slurs which weren’t commonplace here. I’d never heard the word ‘sheeny’ before I interviewed him as a derogatory term for someone who was Jewish. And the schoolyard chants about force-feeding a Jewish child pork, he could recite it from memory. He just came out with them.

He came out to New Zealand when he was 13, it was 1914 and he’d been born in 1901. So he would have spent the bulk of his childhood under those conditions.

What seems surprising is, you notice the sea-change from that dreadful primary school experience to arriving in New Zealand where anti-semitism wasn’t so culturally embedded – but going through to his political years in the 1950s and 1960s, you see all these political rivals, these Citizens & Ratepayers figures who were probably the ‘high society’ types of the day. And they’re the ones the most anti-Jewish vitriol comes from.

Yes! It’s fascinating. The kids he met at Devonport School probably couldn’t tell a Jewish kid from any other – there was no suggestion of any anti-Semitism there and that’s probably part of why he loved it so much. But it was these adults! It was just this small group. And while it seems they cast around for things to dislike him for, clearly – realistically, they must have been anti-Semitic from the start. I have to say I’m still shocked by the degree of it I encountered from some of them.

There’s some quite bracing quotes from some of those fellow counsellors. Again, are those firsthand?

In my other interviews around this, they would just say these things to me…or to others! And he would eventually hear about it.

It seems fortunate that it’s been a work that started so long ago, because all that foundational effort in the eighties came when those friends and rivals were still around, and I would imagine very few of them are now.

That’s right – I think, being a lawyer and being aware of defamation suits, you’re naturally cautious about what you say about people who are living, and what I could have published back then. But they’re all dead. I don’t think any are still around. That whole generation is gone. And with them – I mean, not that all of them were anti-Semitic, but there were enough to make his time in office uncomfortable.

But his detractors were certainly as keen to be interviewed as his supporters. I guess they wanted to tell their side of the story as well. Others, for example Max Tongue, who was another city councilor and part of that Auckland undertaker business, W.H Tongue, on New North Road – he had died quite young but his associates, who were old men by then, were happy to relay what he’d said.

For example, he was once asked to stop criticizing the mayor and replied ‘when you get a bastard like down, there’s only one thing to do and that’s grind your feet into him’.

And in the book, when Robinson hears that Tongue has ambitions to be his mayoral rival, his retort is that ‘he wanted to help Auckland, not bury it’.

He was very witty – he was very quick with repartee. I think that was one of the other reasons why he found his retirement so difficult, because he genuinely liked power, he genuinely liked being to do things with that power, but I think what he truly loved was the cut-and-thrust. Unlike some other people who might have found that city council environment a real bearpit, to a large extent I think he flourished in that political environment.

Those passages – for people who think that the level of political discourse has somehow descended and it’s not as civilized as it used to be, they’re a real eye-opener.

Exactly. It kind of shines a light on things that were reported at the time, but then forgotten about. They were pretty nasty to each other.

Overall – though time catches up with him in the end, the arc the book traces is sort of a political and media establishment that make peace with him. Although he seems abhorrent to them when he first runs for the mayoralty – he ends up being a venerable institution.

I think a lot changes when he makes a comeback after being out of power for a few years in 1968. Those first two terms are really difficult and there’s a dual establishment pitted against him. Come 1968, some of those people have left office and there’s a distinct change. You see the Auckland papers starting to come around as well.

It feels like when he’s gone and they’re left with the nice, genial but not terribly effectual gent for those three years in the middle, they start to realise what he bought to the table.

I think some of them think – well, actually you can be genial and gentlemanly but things don’t get done much – and maybe it’s better to be a bit robust and pushy. If that’s Robinson, then so be it. And towards the end of his career, yes, he becomes the grand old man of local body politics and he sort of does the full circle. He’s anti-establishment and then he becomes part of that establishment – still slightly separate from it, but someone who’s been there long enough to be seen as a big part of the scene.

The other thing the book conjures up which is difficult to imagine today is this very eccentric and archaic patchwork Auckland of little boroughs, innumerable boards for everything, mayors for Mt Albert and New Lynn with the robes and chains and baubles of office.

Even Newmarket was its own borough council. When it was set up in the 19th century it was probably a little hamlet, but that changed very rapidly and suddenly you had all these anachronisms, these little pocket boroughs and dormitory suburbs with their own mayors and councils. I’m still not really sure what they met for exactly, apart to bleat on about how unfair it was they should make a contribution to a metropolitan-wide project while expecting that local amenities be provided to them no questions asked.

I can remember some of them telling me it was so disorganized that they’d lay some drains and then some other board who didn’t communicate and were responsible for power would come along a month later and rip them up because they’d decided to put wires down there. It was incredibly inefficient.

What he always seems to be – though some of his best ideas are ultimately thwarted – is a catalyst for change. He’s working against this orthodoxy that seems bizarre today. Engineers just thought the best way to deal with sewage harmlessly was to dump it directly off Browns Island. Then there was this opposition to his local government reforms to do away with what you were describing. Then most gallingly, he had this incredible rapid rail idea for Auckland and the engineers and experts would come back and say ‘Well, there’s no point doing something like this until congestion gets so bad it becomes necessary’.

And so we’ve never created a proper mass transit system, and what little rail you’ve got, you neglect it to the point that – well, why would you try and use it?

He’s faced by all these people who probably cite their expertise in all these areas, but had no formal education himself. It seems like he did a lot of footwork off his own back.

He was very methodical about basically teaching himself to be an expert on the area he involved himself in. Had the circumstances been different, I think there’s no doubt he would have gotten a university education because he had a magnificent brain. And the few allies he did have were often experts who could back him up. I think he gravitated toward that.

When you spoke with him, do you get a sense of what he felt his greatest achievement was?

I think the Auckland Regional Authority – getting that set up. I have a distinct impression he felt Auckland would have been left ungovernable, and environmentally the worse-off without it. Ultimately, it ensured the preservation of regional parks and things and it was able to better regulate expansion and things, particularly after the advent of the Resource Management Act.

On the other hand, a lot of people would say it was that accomplishment of stopping the Browns Island lunatic system of just dumping the contents of Auckland’s toilets in the Harbour. Just imagine the America’s Cup being held amongst a sea of turds. But I say it’s the fact he was able to survive the beginnings and do what he was able to do.

He ultimately disappeared from the limelight just as the New Zealand political scene reached one of its few historic flashpoints from 1984 onwards. Was he following that all from afar?

Yes – I think throughout the book you get the impression that overall, he was a liberal and a centre-left supporter in the main of the Labour Party, though he didn’t want to be part of it or subject to it. But I think he was very disillusioned by what he saw happening – the direction that the Lange-Douglas government took. I think he would have been delighted about the nuclear-free thing, which he supported avidly, but not so the economic direction. If it had arrived from the National Party you could understand it. Looking back as a person interested in history, I can see that that government needed to be reforming, but I think that it went overboard.

And a reforming government is sort of bitterly ironic, because a tenor of the book is central government obstructing things. He gets excited when Labour come to power in 1972 because they’re making positive noises about rapid rail for Auckland…

And then they let him down as well! Oh, he was supportive of Labour but they were never terribly helpful. It seems like both Labour and National…if they saw a way to avoid costing more money and claim it was to avoid incurring the wrath of the rest of the country, they took it.

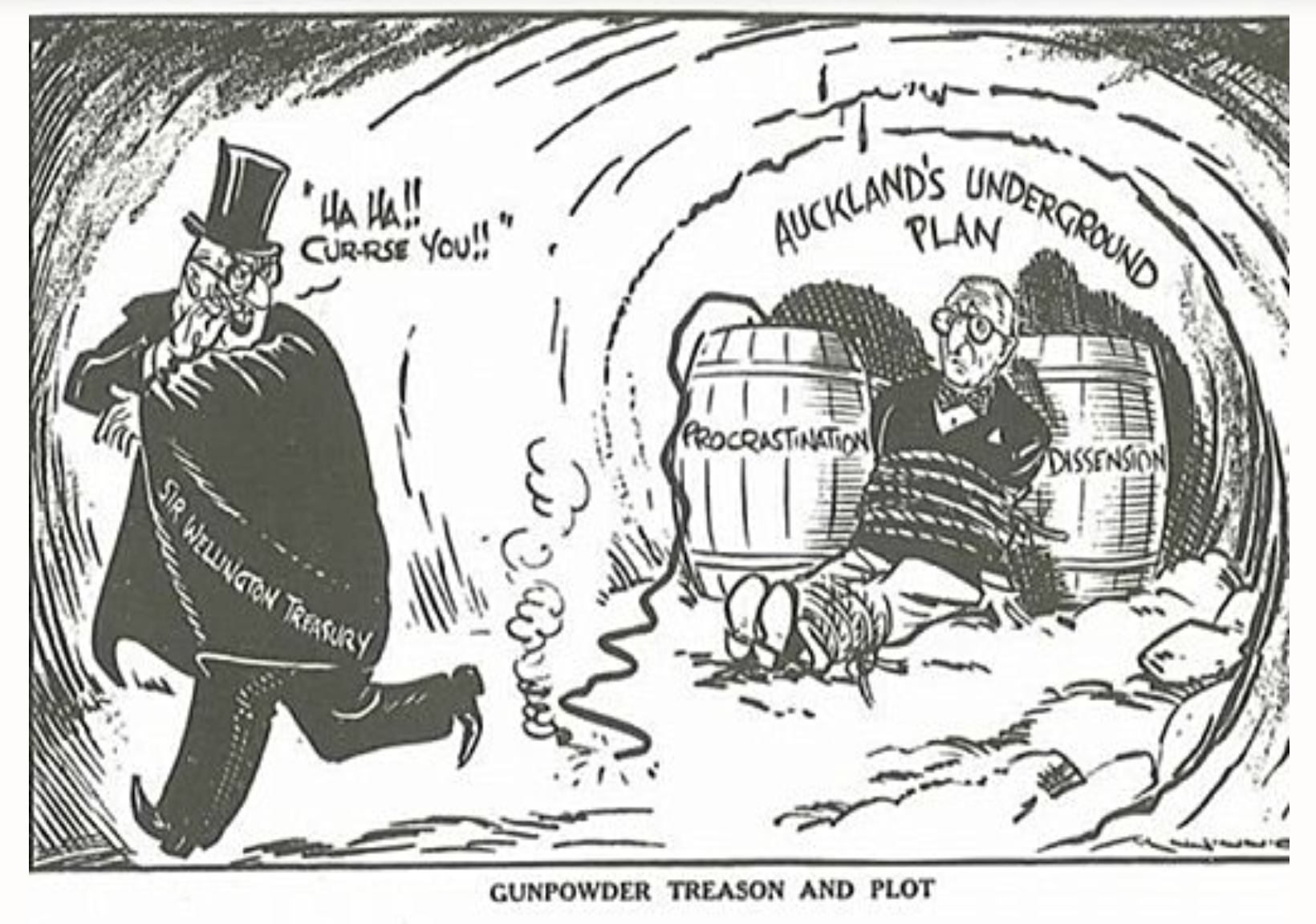

(From The New Zealand Herald of the day - Robinson thwarted by central government. I'm reasonably sure that Treasury, in fact, still dress like this.)

His rapid rail scheme – first of all, it’s remarkable in terms of its vision and scope. The Auckland Plan this year is starting to come round to where he’s at and is encountering some of the same obstacles all over again. But the difference between that and his victory for stopping pollution of the Gulf is that with the Gulf, he started this grassroots network of activists who formed a civil interest group, they built up their own momentum and got Auckland on their side – with the rail, he goes it alone and risks looking like some crank on a flight of fancy. For a great idea, it lacks the same political knack.

I agree – it was definitely run as more of a sole campaign. I mean, he was the huge drive behind the Drainage League, and because of his own wealth he could fund it. But he does harness others, and it’s only by getting that balance of power on the City Council via an elected team that he’s able to delegate who gets put on the City Drainage Board, they push through this scheme for the South Auckland oxidation ponds. But for the rapid rail – he never got together a group of people who could have been a ticket on the ARA – who made the case to the public that they would change the face of transportation and this will happen if we’re elected, and gone through with the mandate to make that happen – and really heavy the government, of whichever ilk, into helping. That was a weakness of his modus operandi.

I’m interested in that statue in Aotea Square. That was one of my favourite monuments even before I knew anything about who Robinson was.

Yes! It was designed, I believe, around 2000/2001 and with the oversight and blessing of Barbara Goodman, his niece – who also served as his mayoress from 1968 to 1980. There wasn’t a row on the idea that a statue should be erected, there was an agreement he was an important enough figure. But the focal point, the way it had it waving his fist against the Council’s own offices – there were some people on there very uncomfortable about that. On the other hand one of the previous ideas, which would have been him shirtless and walking to work, as he liked to, across his usual route from Remuera, was probably even more leftfield for a public monument. I think he had a real sense of humour - it’s the kind of thing that he would have loved.

And Goodman was his mayoress, because after four wives and who-knows how many illicit flings he found himself single in his mid-sixties. This is the flipside of the book I guess – the diligence he put into his career is matched with a total neglect for his family over the years.

Oh, he was terrible. I had a chance to interview Barbara Goodman and a number of Robbie’s sons and daughters from different marriages, and I think they’d made peace and recognized his achievements – but there was no doubt they felt he was a poor father for most of their lives, that he failed to treat their respective mothers well – and it’s true, he hadn’t. It’s his core failing. And then, I think Thelma – his last wife. There, he was truly smitten – I think that was it for him. And then after years of his own flightiness, his infidelity in previous relationships, it was her who left him. He got a taste of his own medicine, and I think it was always something he struggled to recover from.

But the book was never ended to be a hagiography. That wouldn’t have been appropriate. I never intended to – never could have – painted Dove-Myer Robinson as a saint, because he wasn’t.