Unsettling The Score: Graeme Revell, from SPK to Hollywood

Trent Reznor wasn't the first industrial musician to make for Hollywood and do soundtracks - New Zealander Graeme Revell did it twenty-five years ago. We talk to him about his incendiary old group, the realities of film composing, and the strange way things pan out.

Every Sunday afternoon, in a Papatoetoe lounge, Graeme Revell would be surrounded by the same three sounds. His mother, a music teacher, collected opera records and played them on the radiogram. His father was the proud owner of only one piece of vinyl – a slab of “African Drumming” exotica that had come free with the stereo. Maybe as an act of willful stubbornness, maybe because he just liked it, it alternated with the librettos without fail, an alternating loop. Over it all, the choir of the Pacific Islanders Congregational Church round the corner was always singing, always swelling in its pageantry.

Years later, a spare, nasty and awfully effective thriller named Dead Calm made a star of Nicole Kidman and became one of the most successful Australian films ever made. The soundtrack is sparse, but it punctuates all the right points. Sanguine snatches of high opera, a rhythmic male choir’s thrumming heave-and-pull, the arterial beat of tribal drums. Graeme Revell – ten years a toiler in the obscurity of the industrial music scene, occasionally edging into the tabloid music press with a iron-chain live antic, set to be a cult footnote - had drawn on his earliest sonic memories and created his calling card.

Probably without meaning to - at least, no more than anyone consciously constructs their identity – Revell has lived a number of discrete lives. It’s likely few if any of the moguls he’s had to sit through countless post-production meetings with know that he made excoriating synthesiser music in dingy London bedsits in the early 80s; that few of the ritual ambient devotees that see his original group, SPK, as their oft-traded secret have come across Revell’s strident score for the Jennifer Lopez straight-to-DVD bomb Bordertown or his ominous tones for 1998’s Bride of Chucky, the umpteenth retread of the Child Play franchise. And it's not likely that many of his classmates at Otara Intermediate in the 1960s (or his countrymen in general) know that the stoic and square-jawed boy who lived by the church is probably one of the country’s most successful musical exports.

[caption id="attachment_8675" align="aligncenter" width="520"] Otara Intermediate School, 1966. Graeme Revell is fifth in the second row.[/caption]

I speak on the phone to Revell after he’s seen the America’s Cup dwindle to a protracted anticlimax. After a couple of years attempting to live on a super-yacht (it degenerated, he explains, into days lost to bad Internet, a spinning wheel cursor and a static upload bar), he’s on dry land in LA. He’s got kids to pick up in the afternoon, and occasionally, the buzz of someone on a ride-on mower cuts through our Skype chat. It feels like very comfortable domestic bliss, especially from someone who spent a lot of time cultivating unease and decay (or more recently, scoring it).

But then, his beginnings didn’t suggest dark passions in and of themselves, either. He went to Auckland Boys Grammar as an out-of-zoner, finished the stratified experience in 7A. “I guess that old disciplinarian model of education actually has its plusses. If you decide to be something as foolish as a musician or an artist and a writer and you effectively don’t really have a job then the self-discipline you need to be able to work for about ten years for no remuneration whatsoever comes in handy.” Work was a paper run, pay day went to holiday trips to Melbourne. “There was one little boutique store somewhere in central Melbourne and it was run by a German guy who had all these records. And I go hungry for a week just so I could buy one more slab of vinyl and haul them all back to New Zealand. And that’s how I found out about Can, Neu!, Faust, Harmonia, Cluster. So that was really how I got the inspiration out of nowhere to start off, and it wasn’t until later on that I found out there were a few other groups that were similarly inspired.” Within reason: there was no getting around the piano, “but I didn’t really get the point of setting up distortion pedals or setting up thumbtacks or springs in my mother’s. That was definitely a no-no. I didn’t get to do any John Cage prepared piano.”

No formal music training then – a Bachelor of Arts in political science and economics, because a young Kiwi man had to make a respectable start in the world. And then get out.

“I guess I made the right moves geographically. I mean, I went to Sydney, which is the usual trajectory, and then on to London. That’s the fairly frequent trajectory for kids from New Zealand, but to have decided to be a musician and take that trajectory and expect to succeed you don’t… as you know there haven’t been that many New Zealand bands who’ve battled their way through that scenario and succeeded. It seemed like I was wasting my time in my first grad job, so I thought I’d go and work in a mental asylum instead. At least I could help somebody. At the end of the day if I’d cleaned up their crap for them, they might have a slight smile on their face and I’d achieved something.” He found himself a job as an orderly at the Rosehill Psychiatric Unit in west Sydney, moved in with a man named Steven Hill who alternated between being a nurse and a patient himself. He also got his hands on his first synthesizer.

“It was called an EMS synthesizer and it was the synthesizer that did the very first Doctor Who series. The theme song and so on – it actually looked like an old telegraph set-up, where you’d have pins that you’d set up in a matrix and they’d oscillate, and the various filters and so on. And they didn’t even have plug-in cords – that was the next breed. But that to me was the most amazing thing – I began to create the most nasty sounds on Earth, and this is what I’d always wanted to do. “

The EMS had already had a decade’s ambient use, from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to laser-light show prog – but at the flick of a dial it conjured up half a century’s worth of military-industrial electronics, from air-raid sirens to Geiger counters to ECT machines. On his early pieces of work, like “Emanation Machine R. Gie 1916”, Revell pushed the envelope on noxious noise, but it was the context that still makes a lot of SPK’s early work squirm-in-your-seat uncomfortable. Clinically vivid titles, found sound from weapons or cosmetics testing (whichever sounded nastier), a steady heartbeat pulse. Often, SPK’s first two albums feel like snuff audio, live transmissions from the century’s worst state-sanctioned atrocities.

And SPK? It stood for Socialist Patients Kollective, a pro-illness activist group of psychiatric patients who held sit-ins at Heidelburg University in early 1971 and demanded that mental disorders be recognized as an affliction of capitalism they were. It stood for SePeKku, a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. It stood for System Planning K(C)orporation, the American defense contractor that specialized in chemical and biological warfare. It stood for Surgical Penis Klinik, because at the end of the day, they were still a young band in prudish times, and it paid to offend.

But the band’s exact biography remains murky. They lied compulsively to whatever press would cover them, were gone well before the Internet. Various sources credit Graeme Revell (Graham Revel, Revelle, Ravell) as the sole progenitor, just one of a revolving collective, the lone survivor of a band who mostly suicided, and as a opportunistic chancer who inserted himself in the lineup in 1984 and turned them into a glib pop act. And – well, aspects of all these are true.

“There’s been many stories go round," Revell explains. “I have a very fun relationship with rumour and truth – I think if you read Canetti’s Auto Da Fe and you see how rumour can work. Over all these years, I would never correct any rumour that developed. But now I know there are some people who were in the band early on that wanted a bit of credit for what they did, so I’ll give it to them.”

So: conscious of not demystifying it all, and conscious that this isn’t necessarily the truth, here’s what happened. Revell took the name Operator, and Steven Hill the name Ne/H/il. In Sydney, they met a couple of younger guys who completed the live setup (Danny Rumour and David Virgin, each who went on to be successful musicians in their own right). Ne/H/il was more interested in pop; Operator was the reluctant clinician. They made a couple of sneering punk songs that would inevitably get swallowed up in that viscous, swarming drone; their single ‘Slogun’ screams “KILL-KILL-KILL FOR INNER PEACE/BOMB-BOMB-BOMB FOR MENTAL HEALTH”, and orders “therapy through violence”. Even today, it’s almost a three-dimensional assault –every time you play it, it seems to be corroding and splitting the spools it was recording onto, blistering your speakers.

Operator moved to London, where the new incarnation of SPK were frequently loathed. Operator claimed he was ‘stateless’, that the group had no real desire to carry on in music for the rest of their lives, that being a psychiatric nurse was the only job he could ever go back to. Worse, that most journalists were parasites.

They made an NME cover, eventually, with a piece written by someone who hated their latest single. Melody Maker gleefully fact-checked the band’s inconsistent statements, found a Sontag quote at random to link Revell to fascism. Revell, for his part, talked about incorporating the look of PRC revolutionary opera posters from the 1930s, and the writer immediately seized on the inaccuracy. “The less you say, the more likely you are to be successful, because people have nothing to attack you on.” he mused in 1983. “Those guys were vicious,” he chuckles now.

Ne/H/il never joined Revell in the UK, and his suicide is one of the parts of the SPK mythos that’s been subject to the most uncertainty and rumour. In interviews, the group stayed unflappably, even inexcusably glib about the ex-member who killed himself. Today, Revell sees it as a tragedy, but not one he’s happy to adapt for the melodramatic arc of an outfit twenty-five years gone.

“He unfortunately got himself into this relationship that brought out the worst in both he and his wife. It was very difficult with him. He didn’t display any symptoms that you would recognize as being mental illness - it’s very difficult to prescribe medication or treatment to someone who’s just obsessive, in the sense that he would latch onto Chopinhauer, very nihilistic stuff – Yukio Mishima in particular, who did kill himself – and I think that was what it was. He got obsessed with these ideas, but it wasn’t like he would talk about it or evidence it in anyway – you wouldn’t realize there was that big a problem. It was never as if there was a missed opportunity for an intervention – it was just, one day “Oh – shit. He did that.”

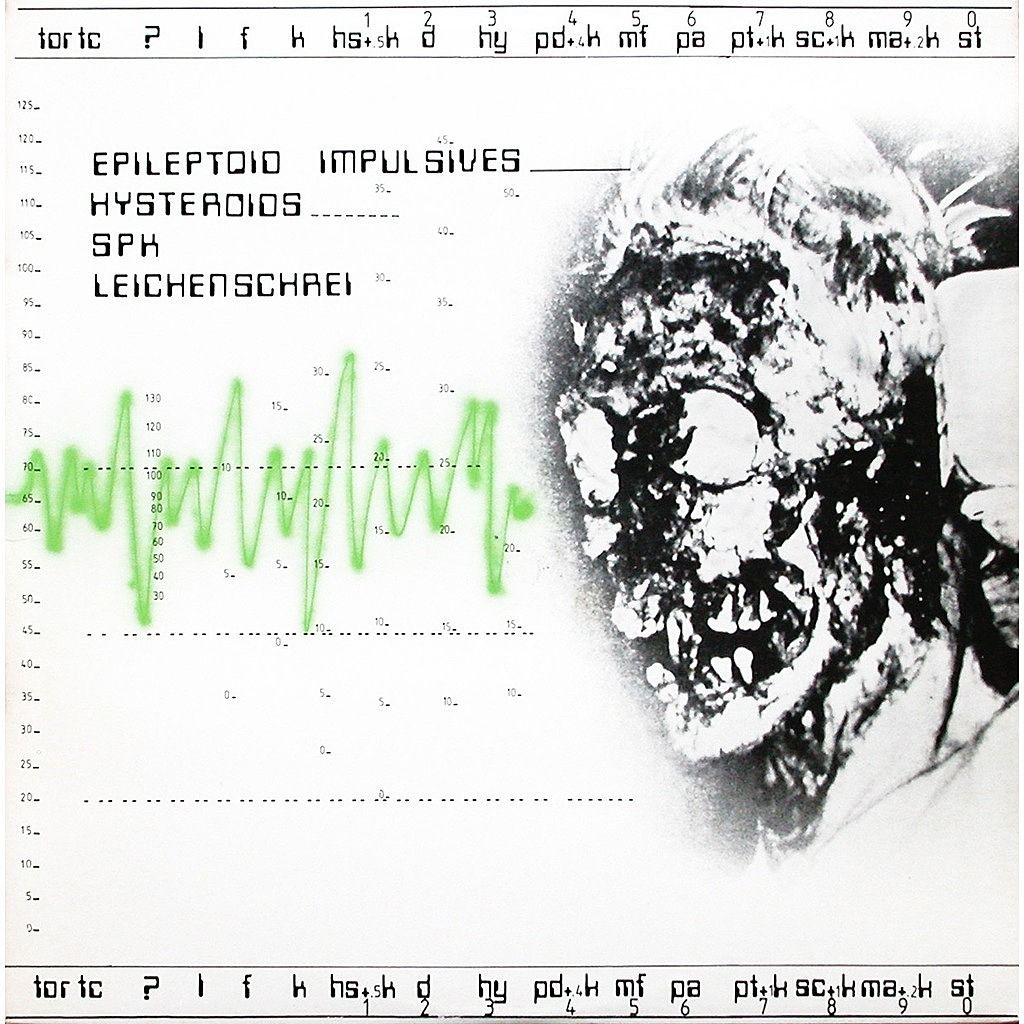

It’d be easy, if lazy, to read some sort of terminal drive into the way SPK presented themselves on their first, decisive records – Information Overload Unit, Leischenschrei, and the ‘singles’ compilation Auto Da Fe. Revell would get passing jobs in college libraries, break into labs and old records, and come out with autopsy footage, deformed corpses, untold mutations. These wound up on their record sleeves, adorning the dense manifestos that came with them, circulating as a semi-notorious VHS nasty overlaid with their live performances. Revell agrees with me that it might seem juvenile in 2013, but argues it should be taken in context.

“When I was in Paris, I started to read Baudrillard, I went to lectures by Foucault and Deleuze – they were the big, cool thinkers of the late ‘70s and early 80s. And I started to get very interested in the idea of information. That’s why the very first album that came out in 1979 is called Information Overload Unit. To me what was going to happen was what J.G Ballard was talking about. This juxtaposition of violence and sexuality – basically everything becoming a montage on top of each other with no real analysis, except in the dusty tomes of the university. The newspapers were doing it, the magazines were starting to do it, and what was happening was effectively an infantilisation of everything.”

IOU’s ‘Macht Schreren’ offers the best example of that info four-car pile up. As synth rumbles and tape unspools, we’re treated to found footage of the administration of anti-psychotics, a mannered narration of the effects of a chemical weapon on a subject, an ad’s exhortations to buy and a porno’s exhortations to cum. The blunt reality of the content robbed stylized sex and violence of their allure; but its presentation channeled a whole manner of developed society’s wider insecurities toward the end of the 70s, as science and medicine lost their beneficent glow and become part of the relentless infodump.

Coming back to SPK’s more graphic and sonically punishing work, I’m not reminded of grindhouse horror, but of a recurring childhood memory of visiting the Auckland Zoo in its older, crueler form. Before we got to the spare brick enclosures, we were led through a chamber of horrors in jars as a special treat. Lost limbs, skeletons of the creatures that had served their time, the stillborn children of the animals we were about to gawp at, preserved in strychnine. The spectacle scratched a vestigial itch I didn’t even know I was meant to have, and Revell’s old group still make me feel uneasy in the same way. I’d argue they made the best industrial noise of their time – but what happened next really set the press onto SPK, and ultimately set Revell himself on a new path.

“I got to the point where I had a young family, I had a son and a daughter and suddenly reality hit. I thought ‘My God, I have to actually make a little bit of money to feed these’.” The result was ‘Metal Dance’: a blatant cross-over attempt (think New Order with less soul and more mallets hitting tins) which he now derides. “I blagged my way into a record company – I represented myself, I managed to convince Warner Brothers to give me enough money to do the record, which I didn’t spend any money on, and it shows. I bought a Fairlight and a house instead.

“The Fairlight was $35,000, which was about a third of what I got from the record company. But then immediately when I got my hand on it, it was amazing. Finally I could realize the things in my head that I couldn’t even get close to with the analogue syntheisiers. That was just a massive step up: being right there at the change from analogue to digital, basically. And from then on, the things that I found I could do really fit in to the desire I had for soundtracks. At the time, I still really loved film. So I did Songs of Byzantine Flowers, which was really a gesture towards soundtracking. And fortunately, I lucked my way into a job.” It was Dead Calm, and the boss of Revell’s Australian label presented him to director Philip Noyce and producer George Miller as a sort of musical mediator.

Revell thought the career had ended as soon as it had begun when he was asked to transfigure a Wagner piece by Miller. The Fairlight CMI was inescapable in early 80s art-rock – a woozy staple of thick, blocky sampling on Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, and Trevor Horn records that was had masses of potential but some fairly practical ceilings on what could and couldn’t be done. “It just sounded like a Wurlitzer.” An attempt to please Noyce with another electronic piece fell flat, and it wasn’t until someone involved happened to come across Songs of Byzantine Flowers propert and its centerpiece, “In Flagrante Delicto”, that Revell became a man they were willing to take seriously. “We developed that, and it seemed to work out quite well.”

The score career juddered, stalled and spurted to life again on a steep learning curve. “I got an interview fairly soon after Dead Calm on The Piano. I remember the interview very well, it was in Jane Campion’s backyard, and she asked me – “Are you a good piano player?” And honestly, and like an idiot, I said no. And so I’d forgotten the first rule of any job interview – lie through your teeth. I hadn’t been for a job interview since high school, if ever – she hired Michael Nyman instead.”

“But when I went to the States, I remembered my first rule of job interviews and when they asked me if I’d ever recorded with large symphony orchestras I said yes! This was 1990, and digital sampling had reached the point where you could fake up a reasonable simile of an orchestra before you got near one. So I was somewhat confident that it was going to sound okay, because it had already sounded okay to me in the studio. But I must admit when I first got front of the orchestra – I didn’t conduct at that time, and I got into the studio and made a total hash of the first cue. I remember putting my head in my hands and thinking “That was a short career.” But, fortunately before I broke down they played it again and the second time through was almost perfect. So I realised that I could lie.”

And so suddenly, he was a Hollywood composer. And that's a career that's offered plenty of highlights – a tender and indelible theme for Wim Wenders’ sci-fi noir Until The End Of The World, the funereal Eastern theme that hangs over The Crow (and so automatically, became the sonic cue for Brandon Lee’s untimely death). With Lori Carson, he made what might have been his last pop song for Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days, a highwater mark for trip-hop as a signifier of futurism. He’s rightly proud of his work on From Dusk Til Dawn – “my pitch on that was a ‘mariachi surf opera’, and really, that should be any composer’s dream”.

But he’s also the person who did the score for Street Fighter: The Movie, for Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie, for Tomb Raider: The Movie. You get the picture. This is what the job of a full-time film composer looks like, and the music he makes for each isn’t bad, or at least never inappropriate (in fact, his Tomb Raider soundtrack is a model of eerie restraint that makes a loud and dumb film seem more evocative than it is). But a good score doesn’t outlive a bad movie, and therein lies a hard truth.

“Here’s my attitude, and I’m sort of sorry to say this sometimes – but there are people who try and elevate film music - of all kinds – to being the great twentieth century classical music, and my opinion is it just isn’t. It’s very straightforward, major/minor or modal writing. The only time you get any kind of originality is usually in the timbres and the sounds and the mixture of elements. But to get through a scene it’s either happy, or sad – and it’s either going forward in action or it’s not – and it can be ironic, which means you’ve got to switch from major to minor frequently. But it’s not rocket science.

“It’s a lot of skills – a lot of political skills, frankly. It’s being in a room and playing off fifty opinions from studios, producers, directors, sometimes actors – and coming out the end with something that vaguely represents music. And frequently it doesn’t. The minute you try to get original or break the box – unless you’ve got either a very experimental or powerful director, it’s probably not going to happen.”

Revell was a film buff years before he’d gone near soundtracking, but it was work like Tarkovsky’s Stalker that captivated him, a complete and compelling synthesis of score and sound editing, built from scratch alongside the picture. He admits he’d still kill to do something like that, if it came along. But the movies he and other composers get are pre-tracked with stock music for every beat. A horror gets a bunch of stings from the last generic horror, a thriller gets a bunch of cues from the last generic thriller. And the job consists of trying not to double-up or repeat what’s already been tracked, but not deviate from it very much. And to still be prepared when someone doesn’t like it and tells you to start again.

“In the film world there’s a lot of power tripping goes on. I think I was sitting in Greece or Croatia or something and I had to make three trips in about eight days to go and “interface” with Jerry Bruckheimer – that’s what they call it. And to interface takes an average time of about 2 minutes. I had to go and sit in LA. He would not Skype. And then the other part of working with Jerry Bruckheimer is he doesn’t know shit about music so the information you’re getting is completely irrelevant and wrong. And that’s also annoying when you’ve just come off a 30-hour flight.”

There’s plenty of cruel twists of fate. So much of Revell’s early work – madness, mutation, and the corruption of science, the enduring love of J.G Ballard – makes him seem like the most natural companion in the world for a David Cronenberg picture, but Cronenberg has used Howard Shore for almost every film he’s ever made. Once, he was second on line for Lord Of The Rings, but Peter Jackson wanted the guy who had scored the 1986 remake of The Fly. Howard Shore, again! “I always say I was insanely lucky to be involved with the business in the first place, but perhaps not quite lucky enough along the way.”

He thinks there are a couple of New Zealand traits that don’t do any favours in Hollywood. “We’re not very demonstrative on the whole. When I first came here, I’d be sitting there quietly listening and translating what they were saying, and I was already hearing the music for their film. After about half an hour, they’d be saying, “Hey, are you really into this? You don’t seem remotely interested.” So there was that one. And I don’t know if it’s personal, or a New Zealand characteristic, but I don’t really suffer fools gladly very well. So I will tend to let that show. Whereas somebody more skilled might not. And they can pick up on my derision quite quickly. And the third thing – I guess it’s a corollary of not being all that demonstrative – I find a lot of movie scenes to be complete schlock, and when they’re asking for the music to also be that, you’ve just got double schlock at the end of the day.”

He received a Lifetime Award a few years ago. The MC welcoming him on stage was the Chucky Doll from Child’s Play (Revell has scored two of the sequels). “Okay, Graeme Revell’s killed sharks, he’s killed bats, he’s killed fog,” the doll blared. “The only thing he hasn’t done and should have done was kill his agent.”

“I’ve actually tried very hard to break the typecasting. I’ve done comedies, I’ve done dramas, but for some reason or another the movie never did any good. Nothing to do with me, but you swim or sink with the movie in this world. It doesn’t matter if you do a great job on a movie that does nothing. Nobody cares. Some of the nicest work I’ve done is on films like Blow. But if nobody sees them you don’t get any more calls – so that’s the way it goes.”

And now, he’s more or less stopping. He has business concerns, a finished screenplay with a tormented trajectory through the biz that makes being the music guy seem like a breeze. He’s working on a requiem: “I’d like to programme music for orchestras or interesting ensembles, but I’m under no illusion that I have very grandiose ideas – so nothing that I write would have less than two orchestras and a choir and some prominent soloists and so on. The chances of it ever being performed are virtually zero. But that’s not ever going to stop me from writing it”. He has a little more than an EMS at his disposal now, but at 58, Revell can afford to be a dabbler again.

“I didn’t get to do some of the things I think I’m capable of doing. I had to give a little speech at this award dinner, and my comment was – “Look, for every one of us in this room, there are twelve thousand guys of equal talent who can’t get in – so shut up.” And that’s really what I feel – that we’re all extraordinarily lucky to be where we are in the first place. Because we all have our own strengths and weaknesses, and I sure know where my weaknesses are.”

In 1986, contributing to Rolf Vasellari's The Judas Jesus, barely 30, he wrote that along with his dreams and aspirations, he harboured fear and doubt. "I feel just as much compulsion to be an architect, for example, as I do a musician. And I feel inestimably guilty that I cannot fulfil the vocation for which I was trained - that of an economist specialising in problems of underdevelopment. My sadness stems from the fact that I do not have several lifetimes to lead." Would he run out of time to do it? Would he end up being heard by millions of people without ever needing to be the celebrity himself, to seep into the collective unconscious by commercial means, to still not be quite satisfied about it? A Hollywood score is honour-bound to each dramatic pause, but real life never sticks to the script.

But his work did change things – and it’s perhaps an irony, perhaps a credit, that you can hear elements of what Revell started in the work of that other industrial musician that transitioned to Hollywood (he's totally civil about Trent Reznor when I ask - "a very lucky gentleman") . “When I first started out in writing – no one had really combined industrial style electronics with more traditional forms. There’s this history in soundtracks of being very literal – like when you see a Chinese scene, you do Chinese music. But I loved the throat singing from Tuva and I liked the duduk from Armenia and I liked all these other instruments, and at the beginning I liked that choir over my mum's opera records - so I chose to use them in contexts that were not ethnically specific. I think you hear a lot of that now. You hear a lot of different instrumentation – basically, any sound can find its place. And maybe, at the end of the day, that’s what I helped achieve.”