An Unpredictable Micro-event: On Nicolás Paris

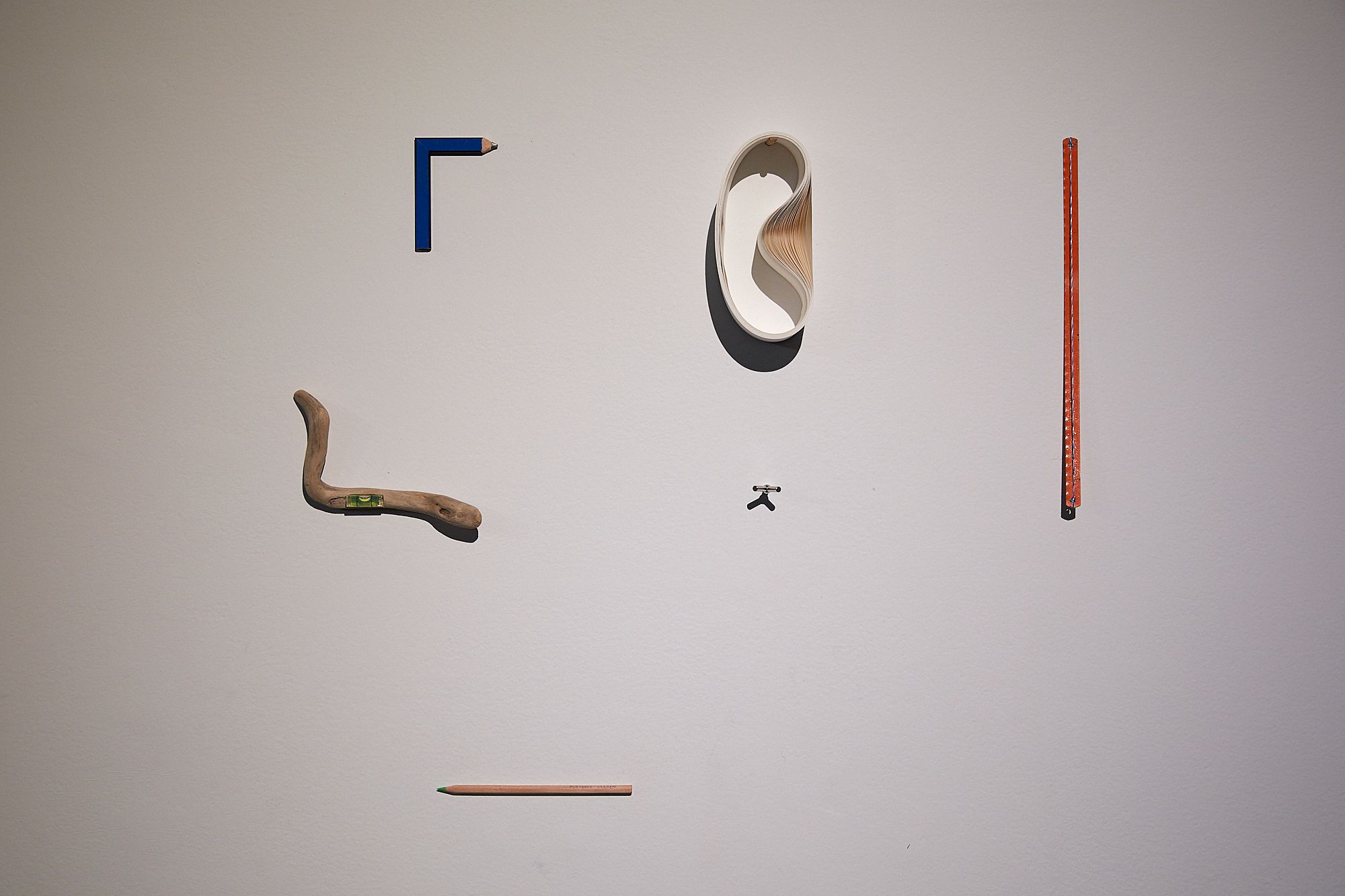

Megan Dunn talks to Colombian artist Nicolás Paris, the latest international artist-in-residence at Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. His exhibition ko ngā herenga kei waenga i a tātou, lo que nos une, what connects us is a perplexing display of plants, short videos and hanging canopies of driftwood.

Colombian artist Nicolás Paris is the latest international artist in residence at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. His exhibition ko ngā herenga kei waenga i a tātou, lo que nos une, what connects us is a perplexing display of plants, short videos and hanging canopies of driftwood. Megan Dunn talks to the artist.

Tool

“Do you want to start here?” Nicolás Paris asked.

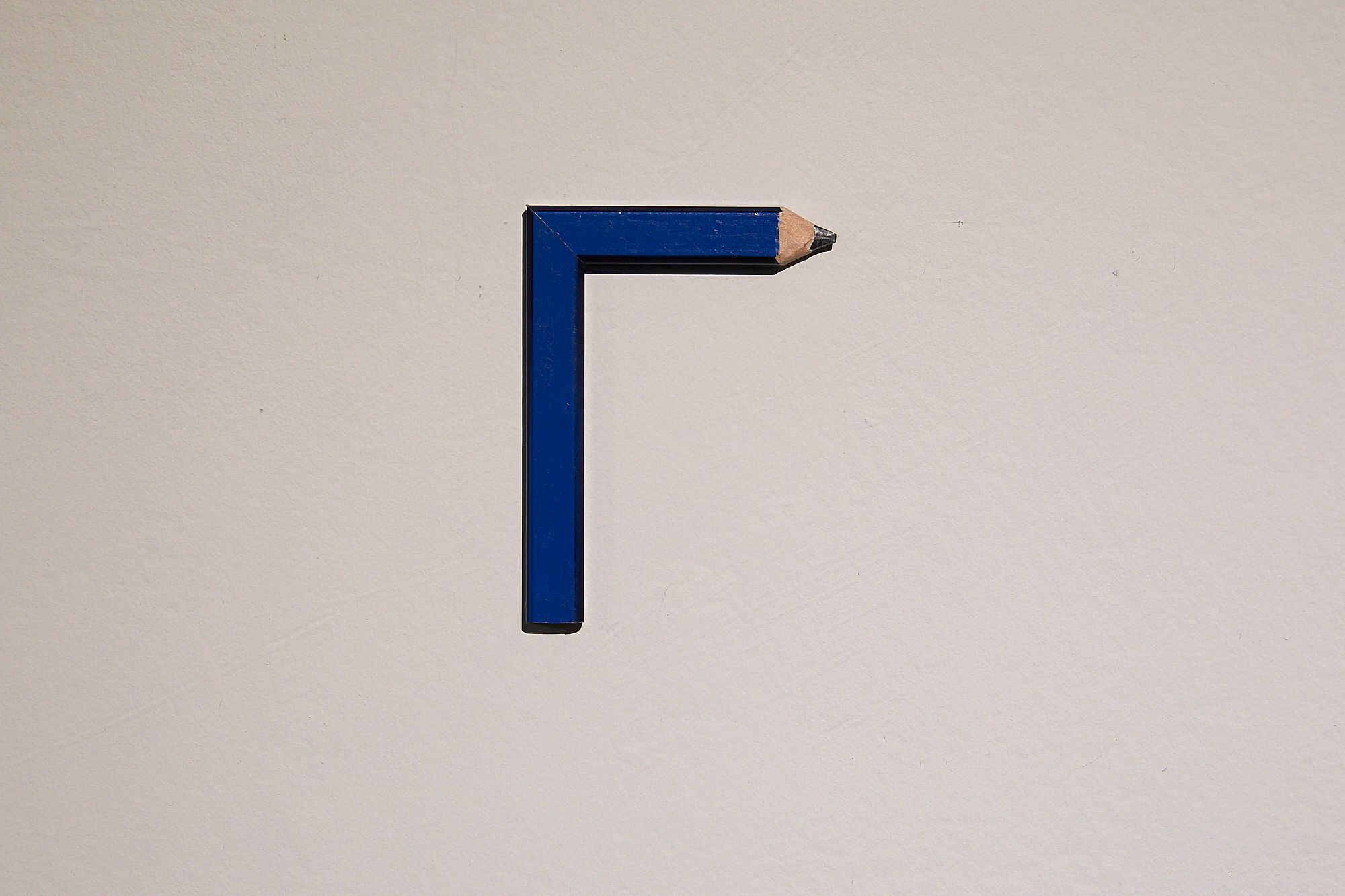

“Yes. Is this a tool? Did you make this pencil?”

We looked at a thick, flat carpenter’s pencil, its blue body now shaped into an L. The pencil was one of several miscellaneous items arranged on the gallery wall.

Nicolás Paris: ko ngā herenga kei waenga i a tātou, lo que nos une, what connects us, 2019, installation view (details), Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Photos (including feature image): Sam Hartnett.

“Normally when you are on a residency the exhibition is the end of your research, but I proposed to overlap my investigation and my exhibition so that the gallery becomes a laboratory. The exhibition is just the platform where everything happens after the opening. And by everything I mean countless activities, exercises, workshops and attempts to produce knowledge and exchange reflections.”

Nicolás Paris had been the international artist in residence at the Govett Brewster Art Gallery for three months when we met. In person, he’s magnetic and open, with the quiet gravitas of a guru. (Not that I’ve ever met a guru.) Paris first studied architecture but quit half way through his degree. “Architecture is my working method.” For several years he worked as a teacher in rural Colombia before he became an artist, at the age of 30. Over a decade into his career, he tells me he is still learning what an artist is. Learning and unlearning are key words in his vocabulary.

We walked through his show together because walking is important to Paris as a peripatetic activity used by the philosopher Aristotle. His exhibition ko ngā herenga kei waenga i a tātou, lo que nos une, what connects us is a perplexing display of plants, short videos and hanging canopies of driftwood, but it’s also a philosophical inquiry into what Paris calls “the geometry between us”.

“The geometry between us is always in flux. It’s something you can change.”

“One of my strategies is to keep adding to my exhibitions. Not just art pieces but also encounters and dialogues that are going to transform this space into a place. From my point of view these items are traces.”

“Traces?” I re-examined the pencil. It had been placed in close proximity to a loop of paper and an errant piece of driftwood.

“When we opened there was only one item on this wall. After the opening, I began to work with different communities and groups around Taranaki. I started to transform the tools we worked with. From my point of view, when an object becomes obsolete it’s really good.”

“Really? Why?” The pencil did look quite good. More assertive than a straight pencil, more dynamic.

“Because it’s not the end. It’s a reboot or a restart for that object. Art is about finding new relationships between objects. For example when you cut and transform a carpenter’s pencil into a square. It doesn't work as a pencil anymore.”

“So, you added that angle to the pencil?”

“Yes.”

Method

The morning I arrived in New Plymouth, Paris was off giving a workshop at a local high school. I first walked around the exhibition ‘cold’, without any access to his ideas. I read the wall text. “Paris conceives of the exhibition as a classroom, a place of learning where there are no teachers or students, only co-participants. In this classroom, we learn from those around us, not just people but all things, animate and inanimate.”

By co-opting the use of an internal stairwell, Paris has rerouted the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery so that co-participants must walk through the Len Lye Centre to reach his show. The entrance to what connects us is marked by an overhanging glass display case of moss and condensation; I looked up at the black moss doing its thing and thought… is that species even technically called moss? I’m no gardener.

Nicolás Paris, what connects us, 2019, installation view, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Photos: Sam Hartnett.

The installation is arranged across four split levels. I stood under a large canopy of driftwood collected from the nearby foreshore with the permission of local iwi. Sanded and smoothed, each torso of driftwood cast a shadow like a wave across the wall. I counted 18 pieces. I felt small and melancholy but I wasn’t sure how much of that was me and how much was the driftwood. Maybe 50/50?

Paris’s videos are also conundrums. One chronicles the whimsical trajectory of a dandelion across the artist’s studio and out into the world. Along the way it sheds one miraculous seed. I assumed it was a self-portrait of the artist. Another video projection shows a fern leaf barely moving.

“Did he film that here?” I asked the gallery attendant.

“That’s a good question.” She walked off to ask another animate being.

What connects us scrambles the hierarchy between nature and culture. On the mezzanine, the gallery floorboards have been removed to create a pair of rectangular gardens. Two toy cars, stones and other objects are positioned in the dirt as though all pieces of the same jigsaw puzzle. The excavated floorboards have been transformed into lids that hang above each garden. On one lid, marbles are placed like tiny planets. Two multi-hued organic loofah sponges are also suspended from the ceiling.

An ambience of quiet, intense concentration, of microscopic forces unseen but sensed.

My impressions? An ambience of quiet, intense concentration, of microscopic forces unseen but sensed. I felt a moral lesson coming on. Plants = good. People = bad. But I wasn’t sure, because at the same time, I thought Paris was quite clearly into the sponges painted in clashing, synthetic colours.

One level down, I examined another small garden of struggling plants and dense, dark, flourishing mold in the area usually occupied by the Govett Brewster stairwell. I noticed a rectangular orange dish sponge nuzzled in the dirt, asserting its identity beyond the kitchen sink.

I picked up a handout from a pile on the floor: “Look around you. Try to shape the space between us, places that are built from the time we share … The way we relate can be a geometric shape.”

Q. But what kind of shape?

Idea

A. boomerang. In the afternoon I returned to the gallery and walked through the show with Paris.

Filmed against a black background, Exogram is a short video of five hands – their fingers splayed into scissors – meeting to form a star. Paris described it as a haiku.

“The branch is the basic structure of any growing system in the universe. Bifurcation can help you to build and understand anatomy. For example the roots of a tree, lightning, our lungs. Nature uses bifurcation to find balance.”

“What is the difference between our bodies and a tree?” He spread his arms.

My mind branched out, synapses firing, I caught his drift.

We admired a video of a tumbling dandelion, filmed in his studio in Bogotá.

“For me the seed is a metaphor for the spectator. Sometimes the spectator is in focus and in other moments they are not focused.”

“That's funny because I thought it was you,” I said.

He paused, “That’s nice. I like the idea that I’m a spectator of the project too.”

“What is the title of this work?” I pointed to the projection of the fern.

“Nastic.”

“Is that the name of the plant?”

“No. Nastic is the scientific name for the movement of plants when they react to the light. In the morning the leaves open, follow the light, and then during sunset close again and go to sleep. The movement of plants is a kind of consciousness. I believe that art happens at the same speed as nature. Really slow.”

Art might happen slowly for Paris, but for me it usually happens quite fast. Yet everything he said, I could see.

Art might happen slowly for Paris, but for me it usually happens quite fast. Yet everything he said, I could see. What connects us was a diagram and now I had the key.

The plants in his installation are from a community garden at Parihaka. When the exhibition closes, he plans to rehome the plants so that “somehow the exhibition can keep growing.”

“I’m not interested in producing art just for human beings. I like to think I am trying to create art for birds and for plants...”

How true. The terrible thing is a plant can’t write a review.

Later we stood on the mezzanine and he told me if I cut open a loofah sponge, I’d see beautiful geometry. An adult sponge has six holes, like a hexagram; a young sponge might have just one hole or three. Gardeners know the right time to pick a pineapple just by looking at the skin and counting the dots. Eight and the pineapple is ripe.

“Geometry is the language of time.”

“How do you know all this stuff?” I asked.

“By talking to people. Biologists, kids…”

In that moment, the huge canopy of driftwood floating in the gallery became a pod of sea creatures cresting and breaching the waves on the foreshore.

“What connects us?” I asked.

“I don’t know what connects us. It could be gravity, it could be luck, it could be language. It could be water, honestly, I don't know. That’s the project.”

System

“My favourite philosopher is the Cookie Monster.”

“What?” I’m no Sheryl Sandberg, but at that point I leaned in. We sat at a café across the road from the gallery and continued talking about his ideas. I held the brochure listing his public programmes. ‘Puzzles in Motion’, ‘Workshop for an Unpredictable Micro-event’ and ‘A Moment for the Unexpected’ are some of his workshop titles.

“For me the workshop is another medium. I try to create an ambiance of exchange. I believe each workshop is a piece of art.”

“Did something unexpected happen during ‘A Moment for the Unexpected’?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said. “Always.”

“What did you do in ‘Puzzles in Motion’?”

He pulled out an old mobile phone and I watched Geometry of Circles by Philip Glass on YouTube. “That’s beautiful,” I said, and meant it.

Paris likes the number 4. DNA is made of 4 components. A sentence has 4 types: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. There are 4 basic mathematic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Paris organises his own working methodology under 4 headings: tool, method, idea, system.

His favourite book is The Anarchist Banker by Fernando Pessoa: “Pure anarchy is based on the idea that each person knows how to be free.”

When he returns to Bogotá, he plans to open an Institute of Radical Learning.

But what is the philosophy of the Cookie Monster?

According to Paris: “Be kind and be generous, especially with cookies. Every time you are generous and kind, you are present. You are just here.”

“That’s going in the review,” I said.

“I want to unlearn everything I learnt in the army in Colombia.”

A week later, I attended the morning session of ‘Workshop for an Unpredictable Micro-event’ at the Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi. The co-participants and I assembled on chairs arranged in a semicircle. Paris asked everyone to give an example of something we wanted to unlearn. It was a hard question to answer for the group and for me.

When it was his turn Paris said, “I want to unlearn everything I learnt in the army in Colombia.”

My mind reeled. I’d missed that detail in New Plymouth. It was a big detail to miss.

As for me, maybe I was sent to meet Paris in order to unlearn my resistance to plants in art? If so, mission accomplished.

My mind isn’t moved by the same things that move Paris. I don’t think art happens at the speed of nature. I don’t want to write a review for a plant or a bird. I prefer things to happen in threes rather than fours. But I do know that meeting Nicolás Paris is an unpredictable micro-event. If you get the chance, don’t miss out.

Nicolás Paris: ko ngā herenga kei waenga i a tātou, lo que nos une, what connects us

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

until 21 July 2019

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.