The Unmissables: Artists to See in September

The best art on show online this month from artists and galleries in Aotearoa.

With galleries still not open to the public in Tāmaki Makaurau, our art critics delve yet again into the digital art world. And not without reservation – viewing art online is just not the same as that palpable, in-the-flesh experience.

This could be why this month's Unmissables keeps close to the artists behind the works. The lives of the artists and the kaupapa they hold close to their hearts. Francis McWhannell speaks to the sad passing of visionary artist Billy Apple, Ngahuia Harrison on kaupapa wāhine and the works of Raukura Turei, and Tulia Thompson to the overt femininity and feminism of Sam Mitchell’s pop portraits.

Instead of sticking solely to dealer galleries this month, our team of art critics has trawled the internet to showcase some of the best and most exciting artists in Aotearoa.

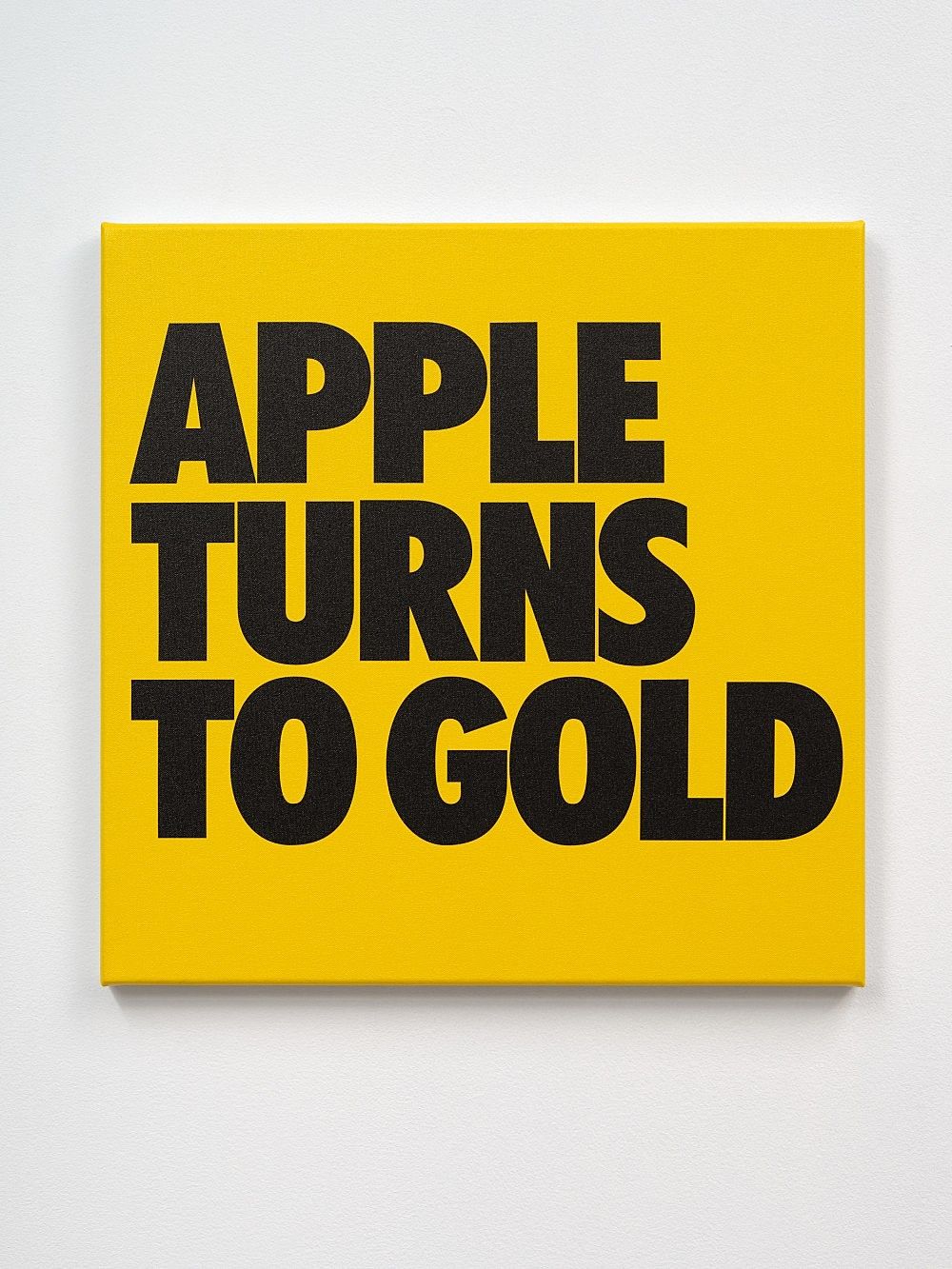

In the early hours of Monday 6 September 2021, during the Level 4 lockdown, Billy Apple passed away in Tāmaki Makaurau. Born Barrie Bates in Auckland in 1935, he adopted his better-known persona in London in 1962, following a course of study at the Royal College of Art. He was involved in the British pop art movement, associating with notable figures like David Hockney (a lifelong friend) and Pauline Boty. In 1964, he moved to New York, where he exhibited in the landmark American Supermarket, alongside key American pop artists, including Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol. He was among the first artists to use industrial technologies like xerography and neon, and was an important force in the development of conceptual art. Between 1969 and 1973, he operated the alternative, not-for-profit space APPLE. He later turned his attention to explorations of the art market. He returned to Aotearoa periodically, and Tāmaki was his home base by 1990. In 2007, Billy Apple became a registered trademark.

Over the past few years, Apple has been highly visible. He has been discussed in books, such as Christina Barton’s Billy Apple®: Life/Work, Anthony Byrt’s The Mirror Steamed Over: Love and Pop in London, 1962, and Thomas Crow’s The Hidden Mod in Modern Art: London, 1957–1969 (all 2020). In 2015, his work featured in International Pop, organised by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki hosted a major retrospective curated by Barton, Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else. Since then, he has shown at his primary dealer galleries, The Mayor Gallery in London and Starkwhite in Tāmaki, at diverse public institutions, such as the Gus Fisher Gallery and Te Tuhi, and at spaces with more complex identities, like Mokopōpaki. Works of his are currently on display at institutions in Edinburgh, Istanbul, and Philadelphia. He has been a generous supporter of galleries. He recently gave work to Toi o Tāmaki and the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. A painting is included in the Artspace Aotearoa fundraising show Kia Tau Rā Anō Te Puehu When the Dust Settles.

I find that lockdowns tend to depress my interest in ‘online content’, but I felt its value in the wake of Apple’s passing. Memorial posts drove home the magnitude of his impact on the art community. While some obituaries highlighted his career achievements, there were also large numbers of fond reminiscences and candid photographs. I had been quite unaware of the extent and range of his personal connections in Tāmaki. I tend to eschew openings; Apple attended them in great numbers. Indeed, he was an enthusiastic gallery visitor in general, often turning up in the company of his wife, Mary Morrison, and his West Highland White Terrier, Macintosh (like the computer). He went to shows to keep abreast of happenings in the art world and to offer support to curators, dealers, and fellow artists of all ages and kinds. He talked with them enthusiastically, performed critiques, and shared knowledge. With Mary, he bought work, and not solely work that shared the taut aesthetic of his own.

It is well known that Apple was prescient in recognising and playing with the notion of the ‘personal brand’. As I dipped into Facebook to watch a video by Tame Iti and scrolled through an Instagram feed peppered with smiling images of Apple in his characteristic translucent spectacles, I was greatly moved to see just how vital personal relationships were to Billy Apple®. – FM

Billy Apple®

Kia Tau Rā Anō Te Puehu When the Dust Settles

Artspace Aotearoa

18 August – 19 October 2021

Image credit: Jennifer French

Billy Apple®, Apple Turns to Gold, 1983–2021

In te ao Māori, there are a number of concepts that indicate the importance of balance: from utu, manaaki and houhou rongo to tapu and noa. Integrated in tikanga-ā-hapū, these concepts work to maintain or restore equilibrium if anything gets out of whack. The introduction of Western patriarchy undermined the prominence of wāhine in Māori society – colonisation upset the balance, but this shouldn’t be a surprise.

It also shouldn’t surprise anyone that Māori have been working hard to recalibrate. Scholars such as Aroha Yates-Smith, Ngahuia Murphy, Ani Mikaere and Leonie Pihama have written extensively on kaupapa wāhine. There are artworks such as Shona Rapira-Davies’ Ngā Morehu (1988), or Robyn Kahukiwa’s Hine Tītama (1980). A current Waitangi Tribunal claim (WAI 2700, the Mana Wāhine Inquiry) investigates the “denial of the inherent mana and iho of wāhine Māori”. In the 2020 exhibition Toi Tū Toi Ora, curator Nigel Borell addressed historical inequities by emphasising wāhine artists. The examples are multiple and include the works of Raukura Turei (Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngā Rauru Kītahi).

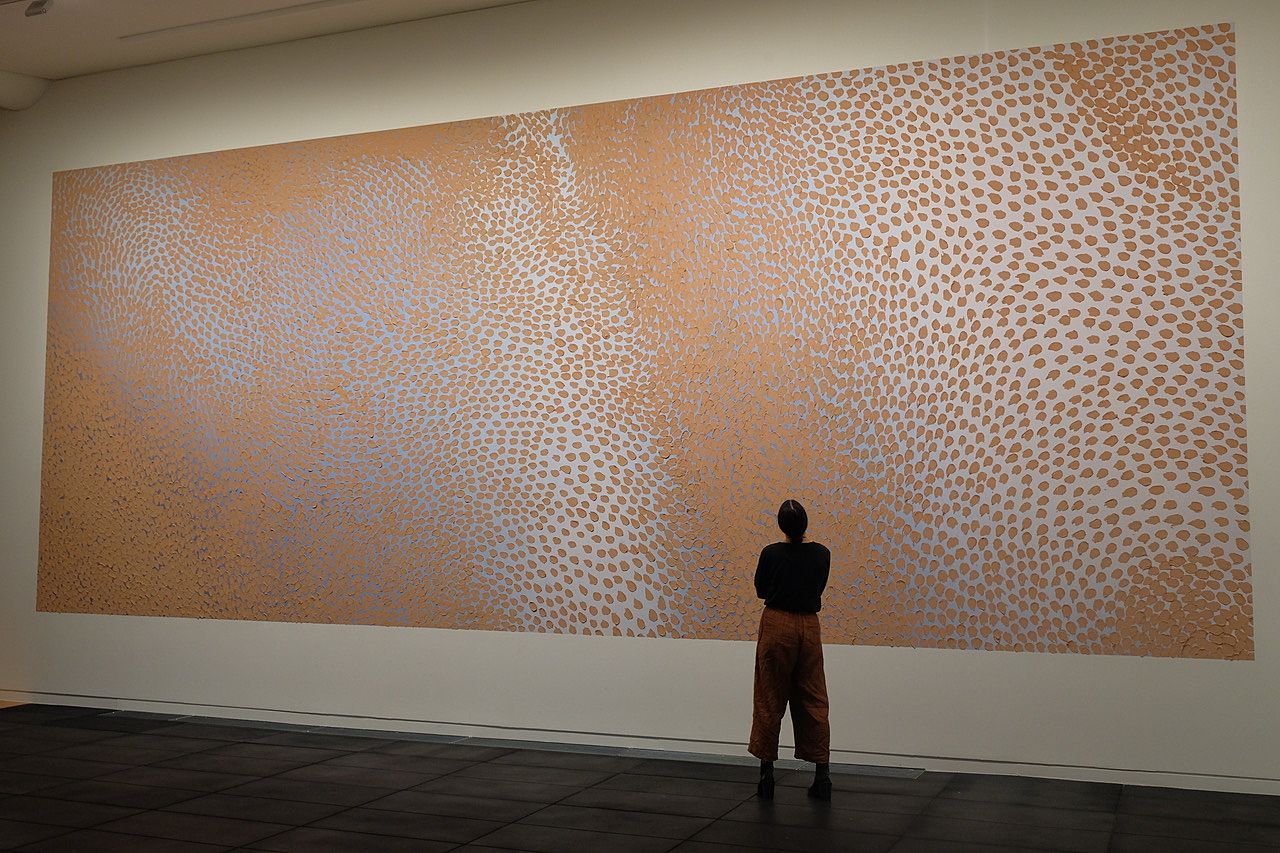

Raukura undulates as an architect, artist, actress, designer; her art practice born of her own personal re-balancing. Pattern on paper became The Grief Series (2017), where swirling and repeated marks evidenced moving through the stagnancy of heartache. Although her practice remains a demonstration in healing, a 2018 commission for the Adam Art Gallery saw Raukura move to utilising uku and exploring ngā māreikura. Te poho-o-Hine-Ruhi (in situ) (2018) is a 4 10m painting using clay and acrylic on top of a digital image of the artist's body – land in human form, or vice versa.

The relationship of wāhine, earth and particularly uku has a rich Māori history. Different tribal lore describes the creation of Hine-ahu-one by Tāne-nui-a-Rangi. To form the first human, Tāne used a specific red soil with the permission and guidance of his mother, Papatūānuku. Raukura has used onepū, black sand, and a blue clay variant, aumoana, sourced from a riverbank in her tribal territory. The earth is then used in layers with oil and pigment to create the textured surface of her artwork. A human form is suggested either through the building or subtraction of layers on the canvas. This entanglement of body and clay reminding us of our cosmogonic narrative. Tāne breathing into the moulded soil, stirring the first signs of life as his breath caused Hine-ahu-one to sneeze – tihei mauri ora! – NH

Raukura Turei

Te poho o Hine-Ruhi (in situ), 2018

I’ve loved seeing Sam Mitchell’s Fourteen online at Melanie Roger during the stressful Level 4 lockdown in Tāmaki Makaurau. Her portraits are scattered with the hearts and swallows of tattoo art as well as retro illustrations. Bright, pop portraits that show her love of Hitchcock films, 19th-century writers and muppets are laboriously painted onto Perspex, so they seem to float forward on the wall. It is an exacting process that means works need to be painted backwards and inverted. The portrait of Roald Dahl has a war plane falling between the eyebrows.

It’s tempting to read these pieces almost as self-portraits that trace her influences, to imagine Mitchell as a 14-year-old girl pulled between the otherworldly Labyrinth and Jane Austen – or to remember myself as a 14-year-old girl. There’s something powerful about art that evokes overt femininity.

Mitchell’s Wuthering Heights 1847 (2021) includes a disturbing 1950s-style illustration of a man forcefully holding a woman, and Catherine surrounded by flames. It reminds me of Kate Bush’s 1978 hit ‘Wuthering Heights’, with her red dress and long, brown hair against a dark line of trees.

The discomfort of remembering yourself as a 14-year-old girl is that the things you loved were not okay. You loved Victorian novels in part because they were a way of exploring adult femininity and love. At the same time as you were mad about love, society was telling you that love wasn’t very important compared to world politics, the economy or rugby. You could only be ironic about love. I loved and then hated the dark love between Catherine and Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. I felt confused and tainted by it.

The ideas that we associate with ‘serious’ art are often associated with masculinity. We have to disavow the colour pink. Artists who are men continue to be taken more seriously.

Mitchell has a fascinating portrait of English painter Jean Cooke that reproduces Cooke’s 1965 painting The Italian Straw Hat on her chest. Pink tattooed roses and blue swallows adorn her face. Jean Cooke was abused by her painter husband, John Bratby, and started painting herself as she wanted to be seen. In Mitchell’s tribute, Jean looks forward resolutely. – TT

Sam Mitchell, Wuthering Heights, 2021

*

The Unmissables is presented in a partnership with the New Zealand Contemporary Art Trust, which covers the cost of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.

Feature image credit: Jennifer French