The Unmissables: Four Exhibitions to see in November

A monthly round-up of notable, controversial and unmissable exhibitions in Tāmaki Makaurau and beyond.

A monthly round-up of notable, controversial and unmissable exhibitions in Tāmaki Makaurau and beyond.

We are amidst the final rush of art ahead of Christmas (that’s right the dreaded ‘C’ word), which means that this month is set for a number of landmark summer shows to open across the country, including two retrospective exhibitions that have had the art communities mumbling and speculating all year. Jacqueline Fahey: Say Something! is opening at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu and, in another homage to one our nation’s most famous painters, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki have partnered to present Gordon Walters: New Vision, opening in Dunedin next week.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg! To help us wade through the rest of the art experiences soon to be upon us, our team have assembled four unmissable exhibitions in Ōtepoti and Tāmaki Makaurau.

Diseases Peculiar to Women

As feminism seems to be entering into mainstream dialogue, Victoria McIntosh’s exhibition Diseases Peculiar to Women at Masterworks Gallery, returns us to “women’s issues” of the 1880s with elegance and humour.

The exhibition’s title is taken from Chapter 30 of the book Robb’s Family Physician. The first page of which is pinned on the wall and discusses menstruation of the “female organism” in cold, condescending (and slightly perplexed) detail.

A handbag hung outside the room is also adorned with a spectacular cascade of pearls, creating a bulbous vagina. Once inside, gallery goers are invited to put on a pair of found gloves and examine altered hand mirrors dispersed amongst painted utensils and a quilted vintage undergarment. On the hidden side of the mirrors are beautifully sewn vaginas made from fabric, lace and pearls. Another set of mirrors are adorned with phrases like “A certain age”, “Showing her age” and ‘Tell-tale signs”.

McIntosh’s work is simultaneously a criticism and subversion of this archaic language. In particular, she examines the idea that aging is a disease peculiar to women in today’s society. Directly confronted with these “symptoms”, they become trivial, contributing to the social re-writing of misogynist text books. – Eloise Callister-Baker

Diseases Peculiar to Women

Victoria McIntosh

Masterworks Gallery

15 October – 18 November 2017

Ex-ante

The latest group show at Artspace, Ex-ante, is a definite unmissable. Laid out in a myriad of blackened out rooms separated by curtains and black walls are six screens with six moving image works. All the artists are internationals except for Fiona Amundsen.

Under the directorship of Remco de Blaaij, this exhibition exposes the nature of documentary making. Ex-ante pulls on the undeniable power structure of documentary, raising the question, who constructs images and through what lens are they being processed? These film makers document communities from specific positions many of them as outsiders, and from there you can’t help but walk away questioning whose truth am I observing.

If you are going to go, make sure you allow yourself an hour or two, to be able to sit through the full running time. Setting you up to consider truth itself as a construct, Ex-ante is demanding on the viewer in the way that good exhibitions should be, and if that is not your cuppa tea, it is still very enjoyable on a purely cinematic level. This is a superb example of how we should be watching moving image art. – Lana Lopesi

Ex-ante

Fiona Amundsen, Tanya Busse and Emilija Škarnulytė, Seamus Harahan, Chia-Wei Hsu, Susan Schuppli

Artspace

27 October – 22 November 2017

Movement Image Time

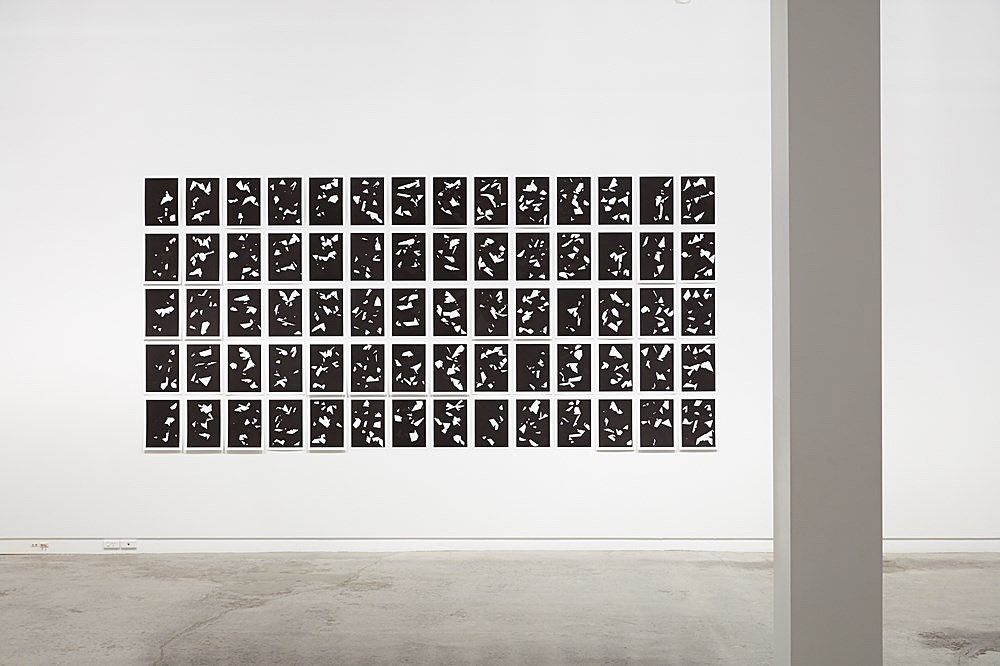

Jeena Shin’s works are well versed in the language of non-objective art. They draw earnestly on its traditions, showing the meticulous execution of the best hard-edge paintings, minimalist chromatic restraint, and the visual pulse of op art. The triangle has long been at the heart of Shin’s practice, populating her works in countless variations. In Movement Image Time, however, this element is less apparent. Instead, irregular white shards blaze through films of charcoal. The forms are complex, but the visual volume has been turned down.

Four monumental paintings in acrylic are arrayed round the gallery space. With their heightened emphasis on effects of transparency and depth, they are absorbing, meditative. In addition to these is a series of prints described as ‘digital photograms’. Produced using surgically precise paper cut-outs and an everyday scanner, the images have been digitally printed onto fine, heavy paper. The resulting works are intensely saturated, possessing a velvety softness that contrasts with the taut sheen of the paintings.

Meanwhile, the crisp edges found on the canvases (created by the removal of masking tape) are echoed in the prints, where the contours appear stamped into the paper. In reality, though, all is flat. Such subtle plays with perception underpin Shin’s practice. In the hands of a less skilful artist, they could easily be dull, but she manages to make them fresh time and again, suffusing work that is superficially tight and cool with pathos, even enchantment. – Francis McWhannell

Movement Image Time

Jeena Shin

Two Rooms

27 October – 25 November 2017

A Pool is not the Ocean

When watching Louisa Afoa’s two-channel video, A Pool is not the Ocean, through the glass of Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s Rear Window, the reflections of two white cars fleetingly overlaid scenes of Afoa seated on a large pink inflatable swan. The white cars threw into contrast the brown body, and by extension Afoa’s concerns with the politics of racialised spaces.

In A Pool is not the Ocean, the adjacent monitors emphasise Afoa’s move from her family home in Papakura to Torbay on the North Shore: from a predominantly brown suburb to a predominantly white one. By subsequently displaying an artwork of the brown body, Afoa enlarges her focus to include the (predominantly) white, middle class art gallery, another racialised space used to frame her work and herself. She does this knowingly, consummately, and powerfully.

Given the impulse of A Pool is not the Ocean, it feels necessary to ask myself: what are the politics of a Palagi reviewing this work? As I write I acknowledge my privilege, my not-knowing, and my inevitable inadequacies.

Often, writing about the work of colonised, marginalised or diasporic artists overlooks or deflates aesthetic considerations, which is certainly a disservice. This may be a misattribution, but I want to say that Afoa takes Jeff Koons’ Balloon Swan (2004–11), owns it, and floats it in what was David Hockney’s swimming pool. This is what self-sovereignty looks like. – Robyn Maree Pickens

A Pool is not the Ocean

Louisa Afoa

Dunedin Public Art Gallery

26 September – 26 November 2017

http://pantograph-punch.com/system/rich/rich_files/rich_files/000/002/519/l/nzcat-3.png

The Unmissables is presented in a partnership with the New Zealand Contemporary Art Trust, which covers the costs of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.