The Unmissables: Three Artworks to See in May

The best art on show in the dealer galleries of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in May 2021.

A monthly round-up of artworks from the dealer galleries of Tāmaki Makaurau that we keep returning to.

This month’s Unmissables delves into the complexities of the practice of rāhui, gazes into the delights of the suburban family and transports us into layers of thick brushstrokes inspired by Cate Kennedy’s prose.

Our team of art critics, Ngahuia Harrison, Francis McWhannell and Tulia Thompson, have trawled the streets of Auckland and online to showcase some of the most exciting art around.

The Waitangi Tribunal’s Report on the Manukau Claim stated that rāhui wasn’t suitable to combat the ”complexities of a modern reality”. Three decades later, Visions Gallery presents Rāhui, by pre-eminent artist Emily Karaka, an exhibition showing just how complex the practice of rāhui truly is.

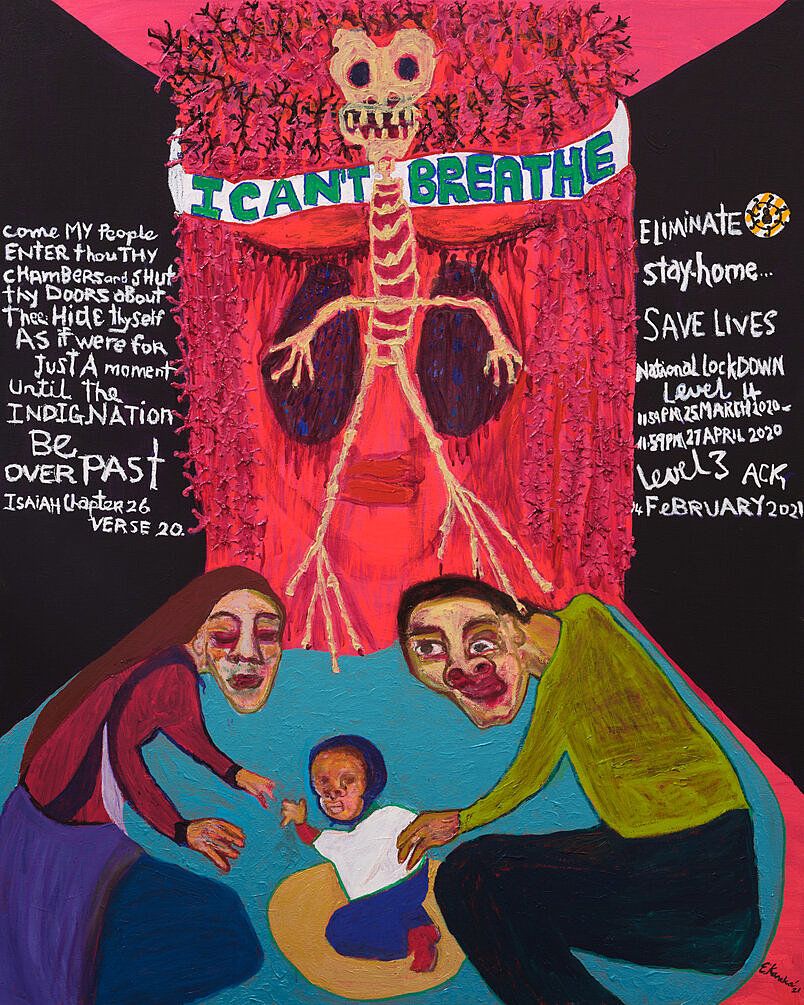

Each painting in the exhibition is loaded with its own politic, lesson or story related to two contemporary sicknesses. In Rāhui Karaka has made neighbours of kauri dieback (and its consequent rāhui), Covid-19 (with its lockdowns), relevant pūrākau and legislation. Acknowledgement is also given to Black Lives Matter in I Can’t Breathe and a nod to Colin McCahon with the biblical reference, Isaiah 26:20. These works were made during Karaka’s McCahon House Residency.

The word pūrākau is often described as ‘myth’, but it is so much more than this. Pū can mean ‘base’ or ‘root’, and rākau translates as ‘tree’. Pūrākau present the complex entanglement or whakapapa of people, place and environment. The painting Moe mai rā, Tohorā illustrates the pūrākau of brothers Tohorā and Kauri. This whakapapa has driven a Northland group called He Manu Taupunga to create rongoā for infected kauri using parts of the tohorā, or southern right whale, currently being trialled. No stranger to colonial legislation and the effects on Māori both in her art work and iwi work, Karaka incorporates the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area Act 2008 in the painting Kawerau ā Maki Rāhui WRHA Act 2008. It was a piece of legislation employed by Te Kawerau ā Maki to prompt support of the Waitākere rāhui by reminding Auckland Council of their obligations to the area.

There aren’t enough words to describe each fulsome artwork and its effect. You really have to stand before these paintings – to see the entanglement of our modern diseases within one embryonic form in the work Pandemic,or the death and life in Te Wao nui a Tiriwa; Kauri Can’t Breathe. In the same way Kauri stooped to receive his brothers’ skin, and now blubber and bone, to cover his vulnerable body – visit Rāhui, with its modern and ancient complexities, and bow your head. - NH

Emily Karaka, I Can’t Breathe, 2021

By the time this edition of The Unmissables goes live, Defences Against the Void will have closed. However, I could not resist covering it. Jacqueline Fahey (born 1929) has received some much-deserved attention of late. In 2017, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū mounted Say Something!, which centred on works from the 1970s. The survey Jacqueline Fahey’s Suburbanites followed, starting at the New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata in 2019 and touring thereafter. Defences Against the Void comprises eleven paintings made between 1957 and the present, and functions as a neat overview of her oeuvre. The show’s compactness invites one to spend time with it, a situation well suited to the works, which are marked by cunning complexity. Most brim with diverse objects and patterns that Fahey improbably manages to balance. At first glance, the pictures delight, and they continue to give the more one gazes.

‘Gaze’ is a good word for Fahey, as Gabriella Stead of Gow Langsford Gallery points out when I visit. All manner of eyes peer out of the paintings. They often belong to the artist or members of her family, but there are also the eyes of pets, toys, squawking gulls, a poster of Bob Marley. At times, the characters look at other entities within the images, setting up compositional sightlines that lead one about the painted spaces. Other visual games are at play. Some paintings include likenesses of earlier ones. Augusta and Lucy taking up the theatre (1981–82) forms the background of Geoffrey back from America (1994) (the works hang together in the show). The reproduction of the former picture in the latter might testify to Fahey’s fondness for it, or to its lingering presence in her studio. Moreover, it sneaks Lucy and Augusta (one of her daughters) in alongside Geoffrey (Augusta’s first husband), producing a whimsical triple portrait.

Mirrors create intriguing spatial effects in the recent In My Studio (2021). The painting nods to art-historical models, such as the so-called Arnolfini Portrait (1434) by Jan van Eyck and Las Meninas (1656) by Diego Velázquez. An empty red velvet chair puts me in mind of papal portraits by both Velázquez and Raphael. Like such old masterpieces, Fahey’s works are wont to wrest control from us, beguiling us into attention. They do this not only through optical trickery and dense detail but also through spell-binding paintwork. In Augusta and Voss (1962), unctuous neutral tones conjure a dim interior, while flashes of paint evoke glasses on a shelf. Teddy bear Voss is a mass of painstakingly rendered fluff. Child Augusta is handled more concisely. There is judicious modelling in her hair, face, and bumpy jersey dress. A lolling block of bright red describes her stockinged legs with startling force, startling conviction. Fahey doesn’t just battle emptiness – she trounces it. - FM

Jacqueline Fahey, Augusta and Voss, 1962, oil on board

Standing in a room of mostly white, monochrome paintings makes you attend to subtleties of texture and colour. The fizz and fall of brushstrokes, thickly layered. Australian painter Jenny Topfer’s exhibition The Taste of River Water at Fox Jensen McCrory takes its name from a poem by acclaimed Australian poet Cate Kennedy, and this collection of paintings feels poetic. It uses the poetic device of limitation to make the viewer notice richness they would otherwise miss. The abstract works create the feeling of landscapes for me, an expansiveness.

Jenny Topfer lives 30 minutes North of Hobart, Tasmania, so I imagine dense hills and the winding of the River Derwent. She orders the waxy oil sticks she uses to create the works from someone in The United States of America. Constructing them is a slow, considered process. She starts several works simultaneously but then builds up layers of paint over 18 months.

In A Far Sea Moves In My Ear (II) (2020), the painting appears pale grey, the effect of blue layers subsumed by white like rock strata. There’s a warmth to this painting; tones of yellow-based cream break through. A feeling of uplift. The intensity of brush marks and slow-layered paint hints at organic structures. To take a line from Cate Kennedy’s poem, “it is so delicate, and so calmly relentless”. - TT

Jenny Topfer, A Far Sea Moves In My Ear (II), 2020, oil and wax pigment stick on linen

.

The Unmissables is presented in a partnership with the New Zealand Contemporary Art Trust, which covers the cost of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.

Feature image: Emily Karaka, Rāhui (installation view), Visions, 2021. Image credit: Sam Hartnett.