The Unmissables: Four Exhibitions to see in July

A monthly round-up of notable, controversial and unmissable exhibitions in Tāmaki Makaurau and beyond.

A monthly round-up of notable, controversial and unmissable exhibitions in Tāmaki Makaurau and beyond.

Hard to believe we’ve taken a full turn around the sun since we first launched The Unmissables. It’s been an exciting year of covering notable, controversial and unmissable exhibitions across Aotearoa, but in the interests of keeping things fresh and thought-provoking, we’re going to take a moment out to reflect and breathe.

But it’s not over quite yet! There’s always so much art to see in Tāmaki Makaurau, and never more so than during Matariki Festival. Fresh Gallery Ōtara’s exhibition Mana Wahine both celebrates Matariki and also ties in with the Suffrage 125 celebrations happening throughout 2018, acknowledging that while Māori women were an integral part of the suffrage movement in Aotearoa, their own narratives are often lost in the dominant version of history. July has also seen a suite of Suffrage 125 exhibitions opening across Pōneke, including The earth looks upon us / Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata featuring Ngahuia Harrison, Ana Iti, Nova Paul, and Raukura Turei at The Adam Art Gallery; Embodied Knowledge at The Dowse; and a solo presentation from Ella Sutherland at Enjoy.

To help you navigate these offerings, our intrepid team of writers has put together four unmissable exhibitions in Tāmaki Makaurau and Pōneke.

Dark Horizons

Dark Horizons presents the work of three Australian Muslim artists responding to complex issues of urban conflict and anxiety in the multicultural South Pacific. Works such as these are not often seen in Aotearoa, yet this exhibition is a timely reminder of the uncertainty brewing on our periphery. Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s seductively crafted The Dogs (2017) greets the viewer with equal parts hostility and animalistic terror. Whatever boundary these hounds are defending – or fleeing from – sets the tone for this anxiety-ridden exhibition.

Three large embroidered works by Abdul Abdullah depict Australian military personnel and the scenic Hindu Kush ranges, the agents and site of ongoing regional conflict in Afghanistan. These images are spray-painted with insidious smiley-faces that erase their deadly intent. Meanwhile, Khaled Sabsabi presents a powerful reflection on contested geographies, selective histories and ideological movements. We Kill You (2016) includes a multi-channel video collaging now-familiar tropes of pseudo-extremist broadcasts with footage of worshippers circling the Kaaba. Directed towards the viewer and our liability to misinterpretation, Sabsabi casts the viewer as both witness and accomplice.

This exhibition, originally conceived and toured by Pātaka Art + Museum in Porirua, seems poignantly placed to arouse our greatest insecurities. Given this era of political intolerance and mass migration, these three artists raise thorny questions about our own positioning and entanglement in global affairs. – Amy Weng

Dark Horizons

Abdul Abdullah, Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, Khaled Sabsabi

Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Art Gallery

2 June – 19 August

Whitu

Kāore te kumara e kōrero mō tōna ake reka.

The kumara does not say how sweet he is.

This whakataukī appears in Whitu, Masterworks Gallery’s Matariki group show, attending a collection of beguiling adornments by Keri-Mei Zagrobelna (Te Āti Awa, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui), which incorporate miniature kumara and whāriki (woven mat) forms made of bronze, copper, and silver. The text notes that Matariki is a time for planting knowledge as well as kumara. Stories are shared, and humble reflection on the past encouraged “so that we can exit the dark months… refreshed and educated.”

Whitu as a whole is modest but powerful, elegantly embodying concepts of sharing and education. Artists from the Masterworks stable have invited other practitioners to show alongside them. Concise and insightful texts have been provided for those with a limited knowledge of te ao Māori. The works included draw on traditional Māori art forms, while embracing non-traditional media and teasing out resonances with peoples and cultures from outside Aotearoa. Terence Turner (Tainui, Ngāti Pākehā), for instance, makes use of jades from Afghanistan and the USA.

Aaron Scythe presents a compelling series of Matariki plates, which riff on the Japanese art of kintsugi, originally a technique for repairing broken ceramics. The product of a long relationship between the artist and Japan, they ingeniously combine pieces of porcelain and stoneware before firing, mixing Japanese patterns and manga-like illustration with Māori motifs, including images of Te Temepara Tapu o Ihoa (opened by a Japanese bishop). To those, like me, who are all too familiar with what Richard Fahey has called “the hegemonic local variant of Anglo-Oriental studio pottery,” Scythe’s works are distinctly refreshing. – Francis McWhannell

Whitu

Mike Crawford, Stevei Houkamau, Roger Kelly, Te Rongo Kirkwood, Neke Moa, Aaron Scythe, Terence Turner, Keri-Mei Zagrobelna

Masterworks Gallery

17 June – 14 July

Short Stories

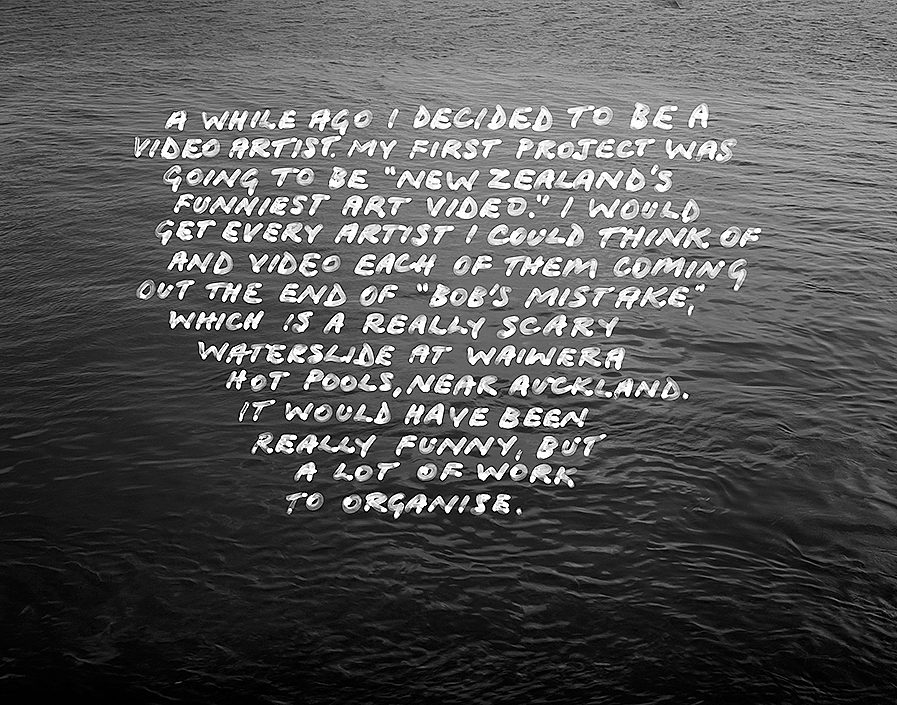

Following the death of a loved one, listing, archiving and cleaning may become ways of remembering and reflecting. We arrange memories so that we may understand and steady ourselves again. In Short Stories at Trish Clark Gallery, Marie Shannon’s video works and silver gelatin photographs grant us insight into her grieving rituals for her partner, Julian Dashper, who died in 2009, and provide reflections upon her own life and career.

Shannon tells the story of transporting a gifted air-horn between old and new family cars. She tells the story of intending to mend a hole next to her son’s bedroom door only to realise it had already been filled long ago, the story of attempting to distinguish a draft from a completed work while going through archives in her and Dashper’s shared Auckland studio. She also shows us faxes from Dashper sent to her during his 1995 artist residency at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen, Germany. These short messages ebb with love and loneliness, made even more bittersweet by Dashper’s reassurances that he is not lonely. Displayed post-mortem, the messages feel profound, as if Dashper is still reassuring Shannon now. Shannon’s works at Trish Clark connect beautifully with the year-long programme currently being presented in the basement space at Michael Lett, which focuses on Dashper’s work.

Shannon uses love, humour, confusion, intelligence and pain in proportioned measures so that the viewer can engage in a layered inquiry into her works. I stayed for a long while at Shannon’s show, then immediately called my mother in tears after I left, reflecting on all the different homes we had lived in, and our own rituals of grieving. Short Stories is an incredibly generous and intelligent exhibition, one that will stay with me for a long time. – Eloise Callister-Baker

Short Stories

Marie Shannon

Trish Clark Gallery

17 June – 21 July

Te reo Pākehā

At a conference some years back, the founder of Christchurch’s Gap Filler, Coralie Winn, talked about getting other people on board with the project, saying, “If you give people a seed, they’re going to stick around to watch it grow, right?” This is the first thought that came to mind when viewing Elliot Collins’ work Rawhaki/Massed, heaped up (2018) in the Toi Pōneke Gallery exhibition Te reo Pākehā from Collins and Martin Awa Clarke Langdon. In an exhibition-label quirk, the components for the work are described as ‘Harakeke seeds, endless supply,’ with the explanation of the work encouraging visitors to ask attendants for their own wooden cup and soil to transport a seed home. The future of te reo Māori relies on seeds being sown within people, the language itself needing nourishment from people for it to be able to grow.

While this is a very simple and inviting work, you can only encounter it by walking past the most sobering work on display. Entitled Tohutō (macrons) (2018), the work is a pile of black leather belts that have been cut at various lengths in reference to the line of the macron, used to elongated vowels. More pertinently, these belts also represent the violence inflicted on Māori school children who were beaten for speaking their own language. This is a historical fact that is often repeated when talking about the loss – and subsequent revitalisation of – te reo Māori in Aotearoa. As someone who has studied this history, it is a reality I am keenly aware of. But seeing that pain materialised in a seemingly benign pile of belts made me very angry. Seeing that pile in close proximity to the school desks that make up the Untitled (te wānanga o Pākehā) (2018) work made me very sad. By their size, the desks show the small stature of those who can sit at them; such small bodies to have had such pain inflicted upon them.

I know very little about Elliot Collins, but Martin I know closely. We work together and share many things in common, including that we are both parents of Māori children who are currently engaged in the New Zealand education system. It is these commonalities, and trust in Martin’s ideas, that will allow me to share the concepts expressed within Te reo Pākehā with my kids. The histories that are extrapolated through each artist’s work are immense, and tinged with pain, but it is important that our children know them, and this exhibition allows us to share them. – Matariki Williams

Te reo Pākehā

Martin Awa Clarke Langdon and Elliot Collins

Toi Pōneke Arts Centre

29 June – 21 July

The Unmissables is presented in a partnership with the New Zealand Contemporary Art Trust, which covers the costs of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.