The Unmissables: Three Artworks to See in February

The best art on show in the dealer galleries of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in February 2021.

A monthly round-up of artworks from the dealer galleries of Tāmaki Makaurau that we keep returning to.

The artworks in this month's Unmissables are challenging. They challenge the racism that was inherent in the trading of taonga centuries ago, and the racism that has trickled down, across and through into contemporary arts institutions. They challenge your heteronormative gaze. They swerve your reading, confronting it head on.

Our team of art critics, Lana Lopesi, Francis McWhannell and Tulia Thompson, have trawled the streets of Auckland to showcase some of the most exciting art on show.

Last year was ostensibly an incredibly bad year for art in this country — but somehow — a lot of good art came out of it too. Gallerists, artists and curators re-evaluated financial models, the precarity of arts work, and the white supremacy built into arts organisations, and they all for the most part came back with some kind of vengeance. New spaces opened, and the biggest exhibition of Māori art Toi Tū Toi Ora curated by Nigel Borell came to life followed by an exposé of Auckland Art Gallery. There was something about arts closure and then rebirth that has made everything feel possible again with a badass attitude. Not only do we get to be indulgent by looking at art in the real again, the element of surprise came back.

So when all of these sexy modernist paintings started popping up on social media, surprised I was. Thirsty Work the latest exhibition by Imogen Taylor at Michael Lett, is in a way a kind of Covid-19 show, with works made in Dunedin, Auckland and Naseby as well as some made in New York before they were packed in a suitcase when the artist had to cut her residency short due to Covid-19. It marks an interesting transition for the artist, where abstracted forms have become more figurative than usual. This approach can be seen in Al Fresco (2021) in particular. By reading the exhibition text, the figurative nature of the bodies seems a bit like iykyk.

“Explicit queer desire as visual protest?…. maybe? The work has moved past being ‘straight-passing’ and now aims to illuminate queer modernisms that still fail to be celebrated.” In Taylor’s comment on the show it seems as if the Mercy Pictures saga that happened last year, and the way in which modernism was used to defend the white supremacist undertones of the exhibition, forced the artist to reflect critically on the stake of her work. I would say the results are pretty bomb. — LL

Thirsty Work

Michael Lett

28 January — 27 February 2021

Imogen Taylor, Al Fresco, 2021. Image courtesy of Michael Lett.

Tim Melville is no stranger to the group exhibition. Like most every dealer in the country, he stages the occasional stable showcase. Just as often, however, he plumps for a more complex project, working with artists represented by other galleries, or not represented at all, in order to produce eclectic exhibitions that serve as celebrations and demonstrate where his priorities lie. Take, for example, his 2016 Pride show, Certainly Very Merry, or last year’s Māori exhibition, Release the Stars. Melville’s current show, Nine Māori Painters, feels especially significant. It nods towards the seminal Five Māori Painters, presented at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in 2014, and clearly connects with Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art, the largest exhibition to be staged by that gallery to date. Seven of the artists in Nine Māori Painters have works in Toi Tū Toi Ora. Another is Nigel Borell, the behemoth’s curator, who recently resigned from Toi o Tāmaki.

Among the twenty-odd pieces on display at Tim Melville Gallery, there are inevitably a few that especially impress me. I chuckle at Ayesha Green’s witty, cartoon-like painting of herself grabbing pizza after voting, which crackles with freshness while remaining carefully composed—as Green’s works invariably do. I stand in silent awe before the paintings of Heidi Brickell (the one artist who does not also feature in Borell’s show), who uses canvas thread to pick out forms that recall carved hei, kōwhaiwhai, and elegant fingers. But as I wander around Nine Māori Painters, my mind returns again and again to Toi Tū Toi Ora, and to the challenges laid down by that tremendous—and by all accounts tremendously popular—exhibition.

Toi o Tāmaki, how can you continue to uplift toi Māori and te ao Māori, even after Toi Tū Toi Ora has come down? What about other galleries in Tāmaki Makaurau and the rest of Aotearoa? Who needs to be elevated, and who needs to step to one side? That Melville’s show has me pondering such things is no accident. In addition to providing a commercial access point for those impressed by Toi Tū Toi Ora, it makes a strong statement. Toi Māori is central, not marginal. It has always been central, not marginal. Until that centrality is adequately reflected in the collection, group, and solo shows presented in Aotearoa, and until we send out into the wider world as many exhibitions as we buy in, every gallerist or curator with a conscience will just have to keep making their position apparent by doing. — FM

Nine Māori Painters

Tim Melville Gallery

10 February – 6 March 2021

Heidi Brickell, Installation view, 2021. Image courtesy of Tim Melville Gallery.

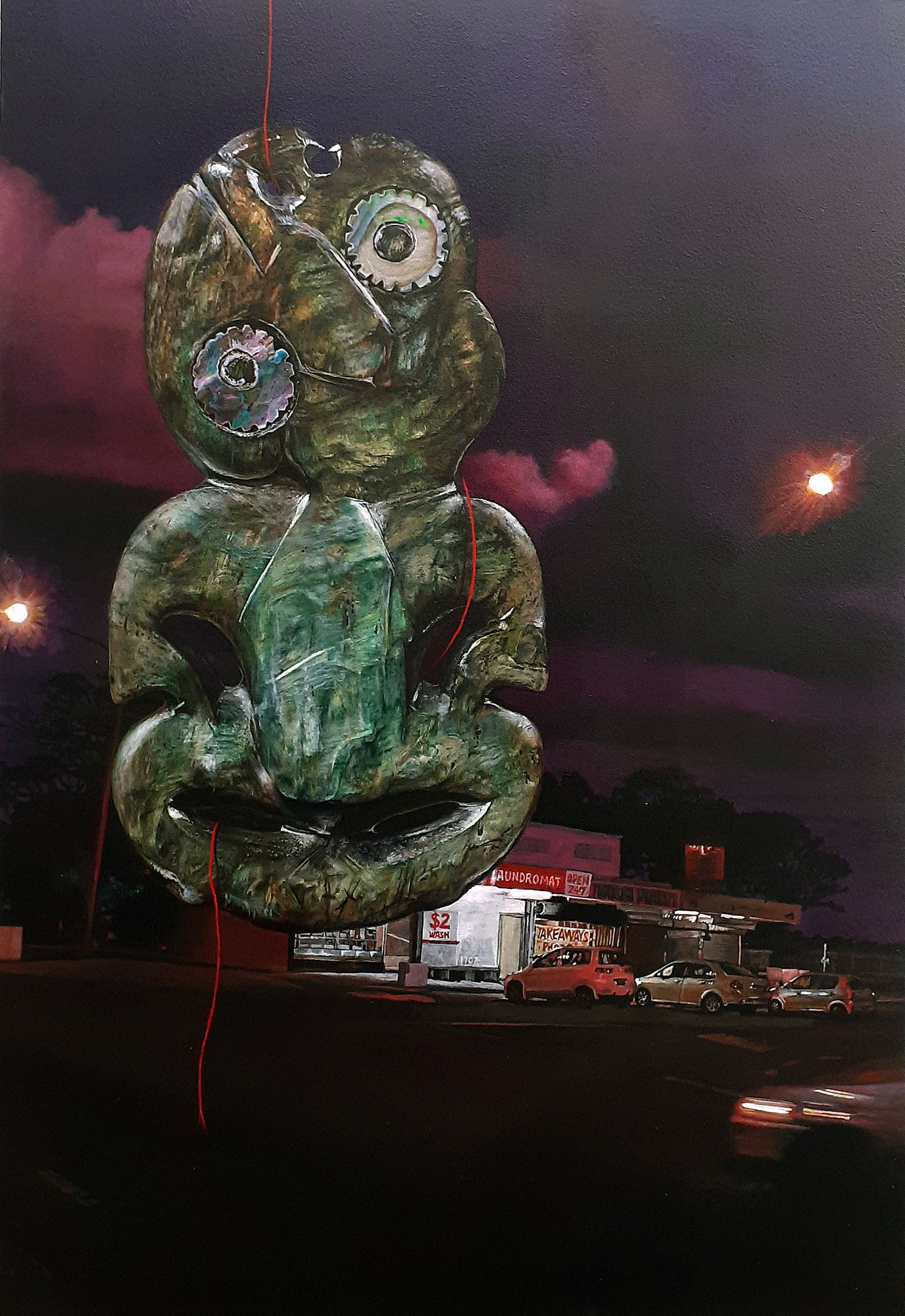

Penny Howard’s (Te Mahurehure, Ngāpuhi) Te Whakahoki, A Sort of Homecoming at Whitespace imagines the return of taonga tūturu sold for big money by global auction giant Sotheby’s. Homecoming feels tangible; in Sotheby’s Lot 14 - Whakahoki, light gleans from the wooden form of te whakahoki at Te Henga, while the sky is mirrored in glistening black sand. It is as if te whakahoki has stepped down from the sky, not been packaged and jostled through international terminals. Te Whakahoki means to return, but also to answer or respond. In one graphite drawing Sotheby’s Lot 94 - Tiaha/ Whakahoki, the darker feathers of a sharp-beaked kotare nestles against the fine feathers of the intricately-carved tiaha. There is a feeling of rising, aided by birds that act as kaitiaki of the taonga.

Sotheby’s Lot 6 - Hei Tiki/ Whakatoki captures the light and hidden depths in pounamu, the way light flows and catches in deep forest, the muddiness and flow. A high level of craft and knowledge is required for representing sacred objects, and I am in awe of how Penny captures the physical materials of pounamu and wood. The paua shell eyes glint differently, one eye is more pink than the other. One hole for threading the taonga has worn through completely, showing its age. The pink tinge from the paua eye is refracted back in pink clouds, the sun has just set over the Glendene corner shops; there is a laundromat with a red '$2 wash' sign in the window and a concrete carpark. You get the sense that homecoming is vital, but also complex and painful. These auctioned, ancient taonga might have been given or stolen or traded – only they hold the knowledge of their arduous journeys. Sotheby’s is still selling Māori taonga, and the taonga of other Indigenous cultures. What accountability should we demand? — TT

Te Whakahoki: A Sort of Homecoming

Whitespace

7 February – 6 March 2021

Penny Howard, SOTHEBY’S LOT 6 - Hei tiki / Whakahoki, 2020. Image courtesy of Whitespace.

The Unmissables is presented in a partnership with the New Zealand Contemporary Art Trust, which covers the cost of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.

Feature image: Ayesha Green, Dominos After Voting, 2020. Image courtesy of Tim Melville Gallery.