Ugly Castles, Vast Prospects: Hearst, Morgan and A Wary American Compromise

Kieran Clarkin didn't go looking for some great American epiphany when he visited the US, but a trip to the West Coast's most famous folly meant he got it. Sort of.

[caption id="attachment_6601" align="aligncenter" width="420"] WR Hearst and J Morgan in a still from a home movie made at the Hearst ranch[/caption]

Some people go to America to find themselves; I went to America to eat the food and drink the wine. I was a few too many years past university to try and emulate some Beat Poet binge, and I'm still a few years too young (not to mention too poor) to make it some leisurely, temperate excursion. As much as I threw myself into gluttonous hedonism, between meals and bowel movements I came to learn a thing or two. For example, did you know that San Antonio, Texas is the seventh most populous city in the union? We did not, until we blundered our way downtown in a rented convertible to be confronted by one-way streets, shoppers and tourists in their throngs. Did you know that one is supposed to get straight back on the Staten Island Ferry to Manhattan, rather than walk around in the freezing cold, looking at nothing? Lesson learned.

But I couldn't help but soak up some history and culture as I wended my way across country - and with it, that urge to make sense of it all. Eventually, wandering around mutely witnessing the sights of California gave me a plethora of opportunities to try and grasp the nature of this vast, influential union. I was on the ground in a state that contained oppression and emancipation, extraordinary wealth and abject poverty, futuristic innovation and deeply conservative values. Like tinkering with the guts of a computer, I was trying to follow the connections and label the components. Occasionally I would fire off a playful observation to the world, but most of the phenomena I witnessed required more explanation than 140 characters would allow. Inevitably, I was drawn to those connections that appealed most to my existing interests: architecture, individuals and history. In San Simeon, CA I found all three: the Big Man who helped shape the USA, his crazy huge house on the hill, and the woman who built it.

*

One of the many tourist destinations friends and fellow travellers added to our list was a trip to Hearst Castle; a lavish collection of buildings on a hill near the California coastline forming the ranch that was one of William Randolph Hearst's multiple residences. Going in almost tabula rasa, it seemed like an opportunity to see some antiquities and witness some American monumentalism. We stopped at the Castle early on our second day driving north. It's a rite of intra-state passage, possibly the most touristy thing to do between Los Angeles and San Francisco (apart from drive the coastal highway itself). Construction on the hill at San Simeon began in 1919, following its owner's ill-conceived bids for political office and the death of his mother. He began in earnest an affair with the stunning screen actress Marion Davies, and embraced his love for the arts and the California coastline.

The experience of visiting this famed residence is well-oiled. You purchase tickets for the coach, separately from another set of tickets from a tiered selection of tours. Your fifteen-minute bus ride is narrated by a recording of Alex Trebek (host of Jeopardy! since 1984) and punctuated by cries from fellow-tourists to look at a particular beast in view (here a coyote, there an elk, everywhere a goat). Nearer the summit, Alex points out the remnants of a mile-long riding colonnade, referred to wryly by its architect as 'the longest pergola in captivity'. You arrive and pile out of the bus to be taken to the front entrance, where the tour begins with a brief and somewhat glossy biography of William Randolph Hearst – the man, the myth, the legend.

Hearst was and is famous for a bunch of reasons, but primarily for being extravagantly rich. The billionaires of today are generally quietly, subtly political; very few of the Forbes Top Ten do anything entertaining. Hearst, conversely, was loud and exciting and did things and made America interesting. Born in 1863 to a family of wealthy landowners, by 1887 he'd taken over management of his father's paper The San Francisco Examiner. He spent the next four decades creating a media empire, attacking corruption with the press and poaching the best talent from nationwide to work on his papers.

He owned 28 papers across the United States, creating the largest newspaper chain in America, as well as being a proto-Hollywood mogul of sorts. From 1903 he spent twenty years in politics, largely unsuccessfully, despite wielding enormous power already. He owned or built a number of properties across the United States which were renowned by the elite names left in their guestbooks. Inextricably, his fate seemed to be tied to that of other noted figures of his period in virtually every other quarter; more successful politicians, less successful millionaires and actors, far less successful journalists, writers and artists. A handful of the more notable names include Charlie Chaplin, Dorothy Parker, Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Charles Lindbergh, Howard Hughes and Winston Churchill. Yet by all accounts Hearst was not an easy-going host, and could run through these personalities quickly: he tightly controlled everyone's intake of alcohol and were one to fall from his favour, they may return to their room and find their bags already packed and ready to leave.

Hearst was also an avid and voracious art collector. The impressive collection of busts, statues, embroideries and paintings that remain at Hearst Castle are only a fraction of his collection at its height. Presciently, this keen eye for art extended to the comic strips that ran in his papers - more than anyone before or since, he employed a number of exceptional American cartoonists.

His method of attracting the best talent with large paychecks was double-edged. He likely made a millionaire of George Herriman, whose Krazy Kat was highly influential in later decades, but made the cartoonist unemployable outside of the Hearst empire. Winsor McCay was only able to continue his Little Nemo for two years under Hearst before being employed solely for political editorial cartoons; an unfortunate end to one of the century's greatest cartooning achievements. Less fortunate men were taken under his wing. They were also grist to his mill.

Richard F. Outcault's Hogan's Alley was an early and famous scalp of Hearst syndication. The lead character of the strip was The Yellow Kid, for whom the Hearst papers' scurrilous and sensational journalistic style would come to be named. 'Yellow Journalism' came to mean the self-promoting, eye-catching and unsupported newspaper style that characterised the Hearst syndication. Editors, journalists and reporters would fabricate stories, interviews and sources in order to sensationalise content, and often whip up nationalistic fervour against perceived aggressors. Hearst's influence is largely blamed for the Spanish war of 1898. Some of the behaviours engaged in at the press would be familiar to any student of today's FOX News; there are parallels to be drawn between the professional lives of Hearst and both Rupert Murdoch and Roger Ailes. A (more insidious) form of yellow journalism lives on.

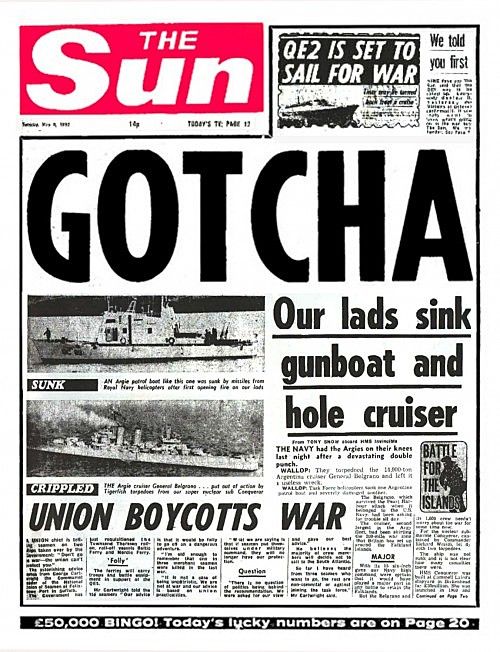

[caption id="attachment_6598" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Top: Hearst's New York Journal in 1898 (the Spanish American War), Bottom: Murdoch's Sun in 1982 (The Falklands). A century separates these bellicose front pages, but little else.[/caption]

His father's fortune was left to his mother, Phoebe Apperson Hearst. He had access to the funds for business and private use, but prior to her death in 1919 he was required to beg for them directly or otherwise raise capital elsewhere. Only after her death, and receiving his full inheritance, did he begin truly building and buying with abandon. He travelled the world purchasing artworks and architectural features and for years outspent his income from the papers, property and mining concerns combined.

Hearst was the big man with the high-pitched voice, an emblem of American free enterprise who relied on a family stipend and the readership of the working class alike - a contradictory and complicated man with layers. Like the country he lived in, there is more subtlety and nuance than the Hollywood portrayal. The 1941 film Citizen Kane features a number of direct parallels to Hearst's life, including a spooky stand-in for his castle named Xanadu. The notions in Kane that the castle was a solitary sanctuary from civilisation, or a palace for his lover, do not hold up well to scrutiny. The ranch and surrounding area was clearly a place he had loved since childhood. It was initially intended as a spring residence for his wife and children and was seldom unoccupied by invited guests.

*

“I would like to build something upon the hill at San Simeon. I get tired of going up there and camping in tents. I'm getting a little too old for that. I'd like to get something that would be a little more comfortable.”

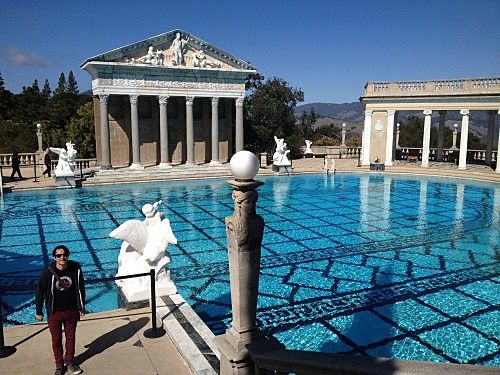

These are reputedly the words by which Hearst announced to his architect his desire to build a cottage where the castle now stands; they are oft-repeated both for the chasmic understatement and the neat visual gag. The place is gigantic. There are three 'bungalows' which each have between ten and eighteen rooms on multiple levels. The main building, called La Casa Grande, comprises twenty-two bedrooms, forty-one bathrooms, and fourteen sitting rooms, among others. We were taken through the ground floor of the Casa Grande, including two sitting rooms, a dining room, a billiards room and movie theatre, meaning the tour was near comprehensive - excluding only about 160 rooms. There are two very large, extremely opulent hand-tiled swimming pools, one of which rests below a never-completed gymnasium, the other overlooks the coastline, framed by a classical Greek temple façade.

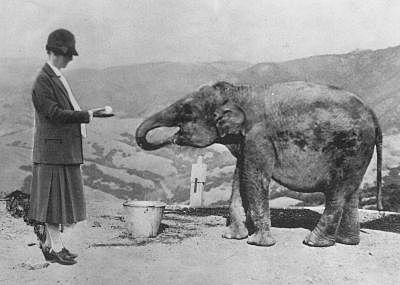

The estate was also home to a large variety of exotic animals. Ever the collector, Hearst corralled animals from all over the world, including giraffes, elephants, kangaroo and camels. The animals held right of way over motor vehicles on the ranch. Most, but not all, were later removed to zoos or died of natural causes; today a thriving herd of zebra will occasionally stop traffic on the highway to the delight of onlookers.

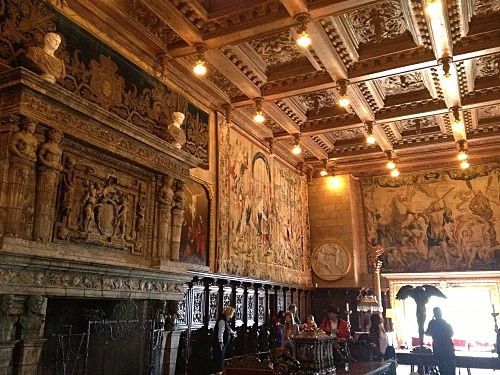

Outwardly, La Cuesta Encantada (as it was officially named) is impressive and harmonious, with all of the buildings designed and decorated in a uniform Neo-Gothic Spanish style. Internally, it's a mess: the construction and ornament represent a hodge-podge collection of elements and artefacts from all over the world. It doesn't seem to follow a single classical school of design and often breaches what the purist would consider good taste. Certainly, a number of artistically minded guests risked Hearst's wrath by writing less than kindly about the horror vacui style of furnishing and the clashing objets d'art. It seemed as if Hearst picked things at random, as they took his fancy. Fifteenth-century Gothic jostles with Greek antiquity, walls are ripped from cathedrals with choir seats intact, merging with ceilings from Spain painted hundreds of years ago.

The tour guide is knowledgable, friendly yet stern, and seems well-indoctrinated into the cult of Hearst. She happily describes his 'avocado' physique, philandering and financial irresponsibility as the minor flaws of an otherwise heroic figure. The tour dwells upon the receptions and dinners with presidents, film stars, and writers, reinforcing the image of Hearst as the wealthy socialite, maintaining his elite financial and social status. My initial impression was that the castle seemed like a very old-world style of displaying wealth (I noted, with no apparent irony, a bust of Caligula). Having studied classics at uni, but little prior knowledge of Hearst, it seemed like the tyrannical whims of an avaricious lout made manifest.

*

Yet a keener eye than mine may have earlier detected the skilled hand of an architect bringing harmony to Hearst's collection of global flourishes. Our tour guide mentions the architect during the initial biography, but it isn't until she's pressed that further information about Julia Morgan is presented. Her sex is noted as unusual for the period, and I make a familiar connection: the forgotten, unsung woman behind the rich and tyrannical Great Man. Here, it seemed, was an example of history remembering the individual with every privilege available to him, while she who overcame real adversity and oppression was overshadowed. I wanted to know her full story. It didn't disappoint.

Morgan studied engineering at UC Berkeley (unusual, yet not unheard of for a female), receiving her Bachelor's in 1894. She was mentored by Bernard Maybeck who encouraged her to seek further training in architecture and pointed across the Atlantic. Morgan moved to Paris in 1896 to study French and revise in earnest for the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. This was the city of Seurat, Cézanne, Rodin and Lautrec - a marvellous place and time for someone interested in the arts. The mixture of Neoclassical Beaux-Arts style and avant-garde galleries provided the basis for innovation in her later career.

She had a small apartment in the Sixth Arrondissement and lived off a fund given to her by her parents. She refused to request any further money, preferring to live frugally and instilling a sense of financial responsibility that would become helpful in budgeting for projects (and stands in contrast to Hearst's profligate financial recklessness). She took the entrance exam for the Ecole des Beaux-Arts three times: her first score too low, her second arbitrarily lowered by male examiners, and her third high enough to embarrass the school were they to again refuse her entrance. Required to complete the course of study before her thirtieth birthday, she now had five years of work to complete in three.

If this is all sounding somewhat Disney, let's throw in the arrival to Paris of her unwell brother who she then had to also support financially. It was around this time that her efforts attracted the attention of one of the wealthiest women in America. Phoebe Hearst reached out to Morgan, offering her financial assistance. A stickler for principle, she turned it down, feeling it would have no effect on the quality of her work. Against the odds, she completed the necessary work to earn her certificate from the Beaux-Arts, becoming the first woman ever to do so.

She returned to California to begin her career, working briefly for another Beaux-Arts alum, John Galen Howard. Morgan terminated their relationship after hearing how he had boasted about the skills of an unnamed architect in his employ, concluding, “And the best thing about this person is, I pay her almost nothing, as it is a woman!”. She became certified as a professional architect and opened her own office in San Francisco in 1904 (another female first) and went on to create a legacy of over 700 buildings. Intentionally or not, she futureproofed her legacy through the earthquake-conscious construction of most of her buildings - the Neptune pool at the Hearst ranch, for example, is actually suspended from reinforced concrete to sway rather than crack.

So when another Hearst came looking for Julia Morgan, it wasn't in search of a feel-good charity case.

Morgan worked on the ranch at San Simeon from the age of forty-eight to seventy-five, completing her involvement in 1947. She had to contend with the physical difficulties of reaching and navigating the site, a disability that affected her balance and the inevitable irregularities of finances received from Hearst. All the while she ran a full-time practice from her San Francisco office, completing the hundreds of other building projects that make her one of the most prolific architects in American history. Her partnership with Hearst, unlike most others in his employ - the cartoonists, the writers, the yes-men - didn't stifle her own ambitions.

[caption id="attachment_6600" align="aligncenter" width="400"] Julia Morgan and a baby elephant[/caption]

My appreciation for the estate grew as we were allowed to wander free in the exterior, witness the swimming pools and admire the view. The details in the periphery - the statues, trim, tile mosaics – and the 127 acres of landscaping embody a sense of craftsmanship and betray an appreciation for the site that was shared by Hearst and Morgan. I realised my idea of Hearst as the domineering egotist, and Julia Morgan as the forgotten, uncredited true artisan was incorrect. Despite their different temperaments - she business-like and dry-witted, he mercurial and impulsive – they shared a number of key interests and traits. Both were determined and intelligent, too determined and intelligent to have treated each other as a folly. The estate is the result of a creative partnership between two talented and driven individuals that lasted twenty-eight years. Apart from their shared taste and knowledge, letters between the two regarding construction demonstrate the extent of their collaboration and mutual respect. There was no exploiter, no victim. The more recent partnership of Steve Jobs and Jonathan Ives is a fairly apt comparison.

Eventually Hearst's compulsive art collecting slowed. In 1937, he began selling off large parts of his collection to alleviate losses suffered in the Depression - though even after Hearst's death, the building still contained enough artifacts to qualify as a museum. The entire ranch was donated by the Hearst corporation to the state of California in 1957. While respecting the approach and achievements of both Hearst and Morgan, I feel like the ranch remains too lavish, too extravagant as a residence. As a museum, though it succeeds wonderfully, and makes me wonder if this wasn't a hidden intention of its creators, who spent three decades bringing it into being.

Talking about the USA is difficult, partly because of its size and diversity, and partly because it is both terrible and wonderful. Doing it in a few words is frustrating, resulting in something facile or slippery at best, or a false single-issue pronouncement at worst. Much of the global face of the US is squabbling politicians, gun violence and greedy excess. When viewed through the lens of news media and internet culture it can often seem like vocal ideologues and hatred have the run of the place. Actually visiting allows one to witness the partnership, community and basic human values that keep everything running. For me, Hearst Castle provided a good micro for the macro - the disjointed mélange of disparate cultures that functions as a whole. Its creators formed an unlikely partnership by finding commonality rather than argument. It might not be to everyone's taste, but together Hearst and Morgan created a singular and superlative way to keep the rain off one's head.